- published: 23 May 2014

- views: 473100

-

remove the playlist1079

- remove the playlist1079

- published: 17 Jan 2014

- views: 414581

- published: 03 Aug 2011

- views: 25551256

- published: 02 Jan 2016

- views: 4250

- published: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 27032

- published: 16 Jan 2015

- views: 7672

- published: 05 Mar 2015

- views: 3336

- published: 05 Mar 2014

- views: 31998

- published: 16 Jan 2014

- views: 22117

- published: 27 May 2016

- views: 133

- published: 24 Jan 2015

- views: 1093

Year 1079 (MLXXIX) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, which means that you can copy and modify it as long as the entire work (including additions) remains under this license.

- Loading...

-

45:29

45:29CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014

CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014

A man launches his friend, an artist at an event. The event is soon raided by some art thieves who try to steal the paintings and end up killing the artist himself. Who were these thieves? Watch as the CID solves this case. "The first thrilling investigative series on Indian Television, is today one of the most popular shows on Sony Entertainment Television. Dramatic and absolutely unpredictable, C.I.D. has captivated viewers over the last eleven years and continues to keep audiences glued to their television sets with its thrilling plots and excitement. Also interwoven in its fast paced plots are the personal challenges that the C.I.D. team faces with non-stop adventure, tremendous pressure and risk, all in the name of duty.The series consists of hard-core police procedural stories dealing with investigation, detection and suspense. The protagonists of the serial are an elite group of police officers belonging to the Crime Investigation Department of the police force, led by ACP Pradyuman [played by the dynamic Shivaji Satam]. While the stories are plausible, there is an emphasis on dramatic plotting and technical complexities faced by the police. At every stage, the plot throws up intriguing twists and turns keeping the officers on the move as they track criminals, led by the smallest of clues."For more information on your favourite show do visit www.facebook.com/SonyLiv and follow us on www.twitter.com/SonyLiv" " -

71:09

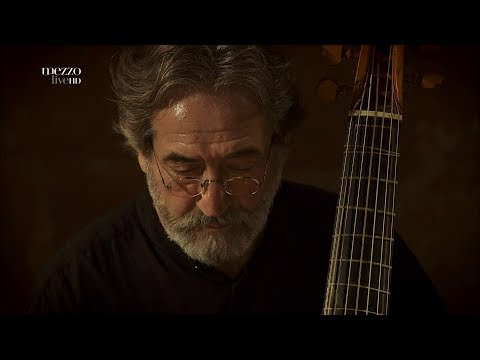

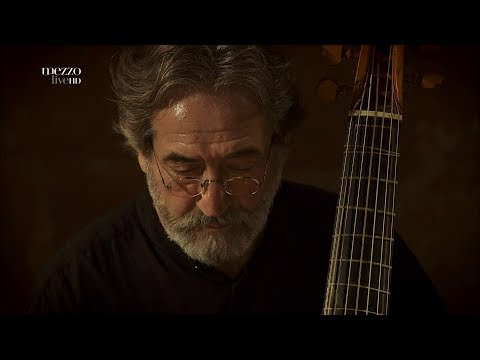

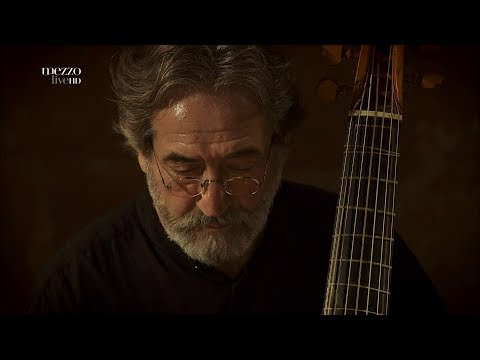

71:09Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi Savall

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi SavallBach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi Savall

__ • Bach: Musikalisches Opfer, BWV 1079 __ 00:00:53 • Thema regium 00:07:28 • Thematis regii elaborationes canonicae • Canon perpetuus super thema regium • Canon 2 a 2 violini in unisono • Canon 1 a 2 cancrizans • Canon 3 a 2 per motum contrarium • Ricercar a 6 • Canon a 4 per aumentationem, contrario motu (a) 00:25:18 • Sonata sopr'il soggetto reale a traversa • Largo • Allegro • Andante • Allegro 00:42:59 • Thematis regii elaborationes canonicae • Canon a 2 quaerondo invenietis (a) • Canon 5 a 2 per tonos • Canon a 2 quaerondo invenietis (b) • Fuga canonica in epidiapente • Canon a 2 per aumentationem, contrario motu (b) • Canon perpetuus per giusti intervalli • Canon a 4 • Ricercar a 6 Encore: 01:07:24 • Orchestral suite no. 2 in B minor: Badinerie __ • Pierre Hantai: harpsichord • Marc Hantai: transverse flute • Manfredo Kraemer: violin • Riccardo Minasi: violin • Bálazs Máté: cello • Xavier Puertas: violone Le Concert des Nations Conducted by Jordi Savall __ -

4:22

4:22The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979

The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979

Official video for Smashing Pumpkins song "1979" from the album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Buy It Here: http://smarturl.it/m91qrj Directed by the team of Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, the video for "1979" won the MTV Video Music Award for Best Alternative Video in 1996. The video for the 1998 song "Perfect" is a sequel to this one, and involves the same characters who are now older Like Smashing Pumpkins on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/smashingpumpkins Follow Smashing Pumpkins on Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/smashingpumpkin Official Website: http://www.smashingpumpkins.com/ Official YouTube Channel: http://www.youtube.com/user/SmashingPumpkinsVEVO -

42:48

42:48Harald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin Test

Harald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin TestHarald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin Test

Show Nr. 1079 | Donnerstag, 25. April 2002 Klassenbuch: Schumi wählt nicht, Toll - Kanzler Duell, Cholesterin-Test / Sven hat einen verspannten Nacken, Schwangerschaften im Team, Promistimmen zu Schumacher, Andrack steht auf lecker Kartoffelbrei, deutsches Wasser, Mülltrennung und ein Kühlschrank aus dem Team (Der rest der Aktion war wohl vorbereitet, wurde aber leider nie ausgestrahlt) / Cholesterintest Gast: Kai Pflaume -

46:32

46:32J. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. Harnoncourt

J. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. HarnoncourtJ. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. Harnoncourt

J. S. Bach Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda musical): BWV 1079 "Regis Iussu Cantio et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta" Nikolaus Harnoncourt - Concentus Musicus Wien Herbert Tachezi (Clavecín) Leopold Stastny (Flauta traversa) Alice Harnoncourt y Walter Pfeiffer (Violín) Kurt Theiner (Viola) Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Viola tenor y Violonchelo) 1. 00:00 Ricercare a 3 (Clavecín) 2. 06:08 Canon perpetuus super Thema Regium (Flauta traversa, violín, viola tenor) 3. 07:08 Canon a 2 (Clavecín) 4. 08:06 Canon a 2 Violini in unisono (Violines, Clavecín y Violonchelo) 5. 09:06 Canon a 2 per motum contrarium (Flauta traversa, Violín, Viola) 6. 09:47 Canon a 2 per argumentationem, contrario motu (Violines, Viola tenor) 7. 11:41 Canon a 2 per tonos (Violín, Viola, Viola tenor) 8. 14:07 Fuga Canonica in Epidiapente (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín, Violonchelo ) 9. 16:02 Ricercare a 6 (Clavecín) 10. 23:13 Canon a 2 (Clavecín) 11. 24:32 Canon a 4 (Flauta traversa, Violines, Clavecín, Violonchelo) 12. 26:41 Trio - Largo (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín, Violonchelo) 13. 32:34 Trio - Allegro (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín, Violonchelo ) 14. 38:59 Trio - Andante (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín,Violonchelo ) 15. 41:47 Trio - Allegro (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín, Violonchelo) 16. 44:57 Canon perpetuus (Flauta traversa, Violín, Clavecín, Violonchelo) VÍDEO SUBIDO EN AGRADECIMIENTO A LA HOSPITALIDAD DE REGINA PORTAL Y JUAN ROJAS ( YURAC CABALLO - CAMARGO - CHUQUISACA - BOLIVIA) -

25:45

25:45Die Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams

Die Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des TeamsDie Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams

Sendung Nr. 1079 vom 25.4.2002 -

23:39

23:39BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015

In 2015, Queensland Rail celebrated 150 years of Rail in the state of Queensland. To mark the celebrations, a steam train hauled by the freshly overhauled BB18 ¼ 1079, hauled a train from Brisbane up the Queensland coast to Cairns and Mareeba and return. We followed the train on its first day, as it steamed its way from Roma Street station in Brisbane to its overnight stop at Maryborough West. Thursday, 15th January 2015 -

38:30

38:30BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015

In 2015, Queensland Rail celebrated 150 years of Rail in the state of Queensland. To mark the celebrations, a steam train hauled by the freshly overhauled BB18 ¼ 1079, hauled a train from Brisbane up the Queensland coast to Cairns and Mareeba and return. On Saturday 16th February 2015, the train made the climb up the scenic Kuranda Range on its way to Mareeba. The locomotive can be heard to slip quite often and we actually stalled a number of times due to the wet and oily rails. -

52:18

52:18Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald Kuijken

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald KuijkenBach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald Kuijken

__ Bach: Musicalisches opfer, BWV 1079 Barthold Kuijken: transverse fute Sigiswald Kuijken: violin Wieland Kuijken: viola da gamba Robert Kohnen: harpsichord __ -

![J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]; updated 16 Jan 2014; published 16 Jan 2014](http://web.archive.org./web/20160529083539im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/crRuvK3jOvs/0.jpg) 72:01

72:01J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]

J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]

Johann Sebastian Bach The Musical Offering/Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079: 1. Thema Regium 2. Ricercar a 3 3. Canon perpetuus super Thema Regium 4. Canon 1 a 2 (cancrizans) 5. Canon 2 a 2 Violini in unisono 6. Canon 3 a 2 per Motum contrarium 7. Canon 4 (A) per Augmentationem, contrario Motu 8. Ricercar a 6 (Cembalo) 9. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Largo 10. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Allegro 11. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Andante 12. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Allegro 13. Canon a 2 Quaerendo invenietis (9A) 14. Canon a 2 Quaerendo invenietis (9B) 15. Canon 5 a 2 per Tonos "Ascendenteque Modulatione ascendat Gloria Regis" 16. Fuga canonica in Epidiapente (6) 17. Canon 4 (B) per Augmentationem, contrario Motu 18. Canon perpetuus [per justi intervali] (8) 19. Canon a 4 (10) 20. Ricercar a 6 (Ensemble) Le Concert des Nations Marc Hantaï [flûte traversière] Pierre Hantaï [harpsichord] Manfredo Kraemer [violin] Pablo Valetti [violin] Bruno Cocset [cello] Sergi Casademunt [viola da gamba] Lorenz Duftschmid [violone] Jordi Savall [viole de gambe, direction] -

0:21

0:21BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079 - video Military Forces Mission Code 1079 ------------- MILITARY CHANNEL NETWORK: MilitarySourceTV: https://goo.gl/HrnGxK MilitaryHardwareTV: https://goo.gl/QNdrTR AirMasterTV: https://goo.gl/mpvD9c NavyForcesTV: https://goo.gl/FUp0db ------ Blogs: http://donaldsharev.blogspot.rs/ https://donaldsharev.wordpress.com/ http://donaldsharev.tumblr.com/ https://twitter.com/DonaldSharev http://donaldsharev.livejournal.com/ https://www.pinterest.com/donaldsharev1/ https://medium.com/@donaldsharev Top Aviation videos from all secret rare military source. interesting content you never saw before. Cool insane jets and helicopters badass scenes from daily exercises planes and weapons in midair refueling, wall share channel topic search 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Most rare videos of jets firing and helicopter manouvering. Ultimate scenes from Navy aircraft carrier USS George Bush CVN77, Harrier Vertical Takeoff and Landings. Ultra Loud Fly By powerful jets like F15, F16, FA18, F35 and F22 close fly over your head close to ground. Heavily armed A10 Thunderbolt Warthog with brutal minigun GAU 8 gatling gun.Exercises with army helicopters like Black Hawks, fast roping --------------- Thanks for watching! Post comment, share, like and subscribe. http://www.ask.com/ http://vk.com/ http://www.yandex.ru/ http://www.liveleak.com/ http://www.wykop.pl/ http://www.bing.com/ http://www.reddit.com/ http://www.google.com/ https://www.pinterest.com/ https://www.facebook.com/ -

12:36

12:36Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079

Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079

Charles Rosen, piano LP, Odyssey, 1969 00:00 Ricercar a 6 07:46 Ricercar a 3 Best Piano Composition; Six Parts Genius By Charles Rosen Published: April 18, 1999 in The New York Times Magazine The keyboard music of Johann Sebastian Bach cannot be called piano music, but there is one magnificent exception. Many musicians consider the six-voice ricercare from ''The Musical Offering'' to be his greatest fugue, and I would choose this as the most significant piano work of the millennium, as it is perhaps the first piece composed for the recently invented piano -- at least, the first piece that a composer knew would certainly be played on a piano. It was on May 7, 1747, that Bach visited Frederick the Great at Potsdam. The Prussian king preferred the pianoforte -- then called ''forte and piano'' -- to the less nuanced harpsichord or the organ; so much so that he had 15 of the instruments built for him. During this visit the king led Bach from room to room to try them out. (Bach had encountered pianos before the royal visit; he had complained that their action was too heavy, their treble too weak.) Frederick played for Bach a theme of his own and then asked Bach to improvise a fugue on it. After Bach obliged with a three-voice fugue, the king demanded a more spectacular six-voice fugue. Bach improvised a six-voice fugue on a theme of his own, but on his return to Leipzig wrote out a six-voice fugue on the royal theme. He had it printed with a number of other works all based on the same theme, and sent it to Frederick as ''a musical offering.'' Along with that other great keyboard work of Bach's last years, ''The Art of Fugue,'' the six-voice ricercare is among the greatest achievements of Western European civilization, and like ''The Art of Fugue'' and ''The Well-Tempered Clavier'' (or Keyboard), it was intended for performance on any of the keyboard instruments that one could find at home -- harpsichord, clavichord, small portable organ or early piano. It goes well on all of them. But if Frederick the Great finally listened to it, he would have heard it on one of his Silbermann pianofortes. The theme is noble, and Bach's development has a richness and a depth of expression that he never surpassed. Like ''The Art of Fugue,'' the ricercare has been arranged for other instruments, but it is essentially a work that has to be played on a keyboard. It can be appreciated above all by the performer: listening is only a poor second for the musical experience of immersing oneself actively in the polyphony, which here has an emotional and physically expressive impact rarely found in a work of music. It is a piece for meditation. The large-scale form is easy to grasp, and the texture is full and complex, moving from one to six voices and back with wonderful contrast. The composition does not emphasize contrapuntal virtuosity, but rather richness of harmony. The imaginative invention is dazzling. The 20th century rediscovered ''The Musical Offering,'' but pianists have yet to claim this greatest of fugues as their own.

- 1050s

- 1060s

- 1070

- 1070s

- 1075

- 1076

- 1077

- 1078

- 1079

- 1080

- 1080s

- 1081

- 1082

- 1090s

- 10th century

- 1100–1109

- 1107

- 1142

- 11th century

- 12th century

- 2nd millennium

- Ab urbe condita

- April 11

- Armenian calendar

- Assyrian calendar

- August 8

- Bahá'í calendar

- Bengali calendar

- Berber calendar

- Bolesław II the Bold

- Buddhist calendar

- Burgos

- Byzantine calendar

- Category 1079

- Category 1079 births

- Category 1079 deaths

- Chinese calendar

- Coptic calendar

- Emperor Horikawa

- Ethiopian calendar

- Gregorian calendar

- Halsten

- Hebrew calendar

- Hindu calendar

- Holocene calendar

- Håkan the Red

- Inge the Elder

- Iranian calendar

- Islamic calendar

- Japanese calendar

- Julian calendar

- Kali Yuga

- Korean calendar

- Kraków

- List of centuries

- List of decades

- List of years

- Millennium

- Minguo calendar

- Monastery

- New Forest

- Omar Khayyám

- Persian people

- Peter Abelard

- Poland

- Regnal year

- Republic of China

- Roman numerals

- Sexagenary cycle

- Thai solar calendar

- Vikram Samvat

- William I of England

-

CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014

A man launches his friend, an artist at an event. The event is soon raided by some art thieves who try to steal the paintings and end up killing the artist himself. Who were these thieves? Watch as the CID solves this case. "The first thrilling investigative series on Indian Television, is today one of the most popular shows on Sony Entertainment Television. Dramatic and absolutely unpredictable, C.I.D. has captivated viewers over the last eleven years and continues to keep audiences glued to their television sets with its thrilling plots and excitement. Also interwoven in its fast paced plots are the personal challenges that the C.I.D. team faces with non-stop adventure, tremendous pressure and risk, all in the name of duty.The series consists of hard-core police procedural stories deali... -

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi Savall

__ • Bach: Musikalisches Opfer, BWV 1079 __ 00:00:53 • Thema regium 00:07:28 • Thematis regii elaborationes canonicae • Canon perpetuus super thema regium • Canon 2 a 2 violini in unisono • Canon 1 a 2 cancrizans • Canon 3 a 2 per motum contrarium • Ricercar a 6 • Canon a 4 per aumentationem, contrario motu (a) 00:25:18 • Sonata sopr'il soggetto reale a traversa • Largo • Allegro • Andante • Allegro 00:42:59 • Thematis regii elaborationes canonicae • Canon a 2 quaerondo invenietis (a) • Canon 5 a 2 per tonos • Canon a 2 quaerondo invenietis (b) • Fuga canonica in epidiapente • Canon a 2 per aumentationem, contrario motu (b) • Canon perpetuus per giusti intervalli • Canon a 4 • Ricercar a 6 Encore: 01:07:24 • Orchestral suite no. 2 in B minor: Badinerie __ • Pierre Hantai: harp... -

The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979

Official video for Smashing Pumpkins song "1979" from the album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. Buy It Here: http://smarturl.it/m91qrj Directed by the team of Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, the video for "1979" won the MTV Video Music Award for Best Alternative Video in 1996. The video for the 1998 song "Perfect" is a sequel to this one, and involves the same characters who are now older Like Smashing Pumpkins on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/smashingpumpkins Follow Smashing Pumpkins on Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/smashingpumpkin Official Website: http://www.smashingpumpkins.com/ Official YouTube Channel: http://www.youtube.com/user/SmashingPumpkinsVEVO -

Harald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin Test

Show Nr. 1079 | Donnerstag, 25. April 2002 Klassenbuch: Schumi wählt nicht, Toll - Kanzler Duell, Cholesterin-Test / Sven hat einen verspannten Nacken, Schwangerschaften im Team, Promistimmen zu Schumacher, Andrack steht auf lecker Kartoffelbrei, deutsches Wasser, Mülltrennung und ein Kühlschrank aus dem Team (Der rest der Aktion war wohl vorbereitet, wurde aber leider nie ausgestrahlt) / Cholesterintest Gast: Kai Pflaume -

J. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. Harnoncourt

J. S. Bach Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda musical): BWV 1079 "Regis Iussu Cantio et Reliqua Canonica Arte Resoluta" Nikolaus Harnoncourt - Concentus Musicus Wien Herbert Tachezi (Clavecín) Leopold Stastny (Flauta traversa) Alice Harnoncourt y Walter Pfeiffer (Violín) Kurt Theiner (Viola) Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Viola tenor y Violonchelo) 1. 00:00 Ricercare a 3 (Clavecín) 2. 06:08 Canon perpetuus super Thema Regium (Flauta traversa, violín, viola tenor) 3. 07:08 Canon a 2 (Clavecín) 4. 08:06 Canon a 2 Violini in unisono (Violines, Clavecín y Violonchelo) 5. 09:06 Canon a 2 per motum contrarium (Flauta traversa, Violín, Viola) 6. 09:47 Canon a 2 per argumentationem, contrario motu (Violines, Viola tenor) 7. 11:41 Canon a 2 per tonos (Violín, Viola, Viola tenor) 8. 14:07 Fuga Canonica in Epid... -

Die Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams

Sendung Nr. 1079 vom 25.4.2002 -

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015

In 2015, Queensland Rail celebrated 150 years of Rail in the state of Queensland. To mark the celebrations, a steam train hauled by the freshly overhauled BB18 ¼ 1079, hauled a train from Brisbane up the Queensland coast to Cairns and Mareeba and return. We followed the train on its first day, as it steamed its way from Roma Street station in Brisbane to its overnight stop at Maryborough West. Thursday, 15th January 2015 -

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015

In 2015, Queensland Rail celebrated 150 years of Rail in the state of Queensland. To mark the celebrations, a steam train hauled by the freshly overhauled BB18 ¼ 1079, hauled a train from Brisbane up the Queensland coast to Cairns and Mareeba and return. On Saturday 16th February 2015, the train made the climb up the scenic Kuranda Range on its way to Mareeba. The locomotive can be heard to slip quite often and we actually stalled a number of times due to the wet and oily rails. -

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald Kuijken

__ Bach: Musicalisches opfer, BWV 1079 Barthold Kuijken: transverse fute Sigiswald Kuijken: violin Wieland Kuijken: viola da gamba Robert Kohnen: harpsichord __ -

J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]

Johann Sebastian Bach The Musical Offering/Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079: 1. Thema Regium 2. Ricercar a 3 3. Canon perpetuus super Thema Regium 4. Canon 1 a 2 (cancrizans) 5. Canon 2 a 2 Violini in unisono 6. Canon 3 a 2 per Motum contrarium 7. Canon 4 (A) per Augmentationem, contrario Motu 8. Ricercar a 6 (Cembalo) 9. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Largo 10. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Allegro 11. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Andante 12. Sonata sopr'Il Soggetto Reale: Allegro 13. Canon a 2 Quaerendo invenietis (9A) 14. Canon a 2 Quaerendo invenietis (9B) 15. Canon 5 a 2 per Tonos "Ascendenteque Modulatione ascendat Gloria Regis" 16. Fuga canonica in Epidiapente (6) 17. Canon 4 (B) per Augmentationem, contrario Motu 18. Canon perpetuus [per justi intervali] (8) 19. Canon a 4 (10) 20.... -

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079 - video Military Forces Mission Code 1079 ------------- MILITARY CHANNEL NETWORK: MilitarySourceTV: https://goo.gl/HrnGxK MilitaryHardwareTV: https://goo.gl/QNdrTR AirMasterTV: https://goo.gl/mpvD9c NavyForcesTV: https://goo.gl/FUp0db ------ Blogs: http://donaldsharev.blogspot.rs/ https://donaldsharev.wordpress.com/ http://donaldsharev.tumblr.com/ https://twitter.com/DonaldSharev http://donaldsharev.livejournal.com/ https://www.pinterest.com/donaldsharev1/ https://medium.com/@donaldsharev Top Aviation videos from all secret rare military source. interesting content you never saw before. Cool insane jets and helicopters badass scenes from daily exercises planes and weapons in midair refueling, wall share ... -

Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079

Charles Rosen, piano LP, Odyssey, 1969 00:00 Ricercar a 6 07:46 Ricercar a 3 Best Piano Composition; Six Parts Genius By Charles Rosen Published: April 18, 1999 in The New York Times Magazine The keyboard music of Johann Sebastian Bach cannot be called piano music, but there is one magnificent exception. Many musicians consider the six-voice ricercare from ''The Musical Offering'' to be his greatest fugue, and I would choose this as the most significant piano work of the millennium, as it is perhaps the first piece composed for the recently invented piano -- at least, the first piece that a composer knew would certainly be played on a piano. It was on May 7, 1747, that Bach visited Frederick the Great at Potsdam. The Prussian king preferred the pianoforte -- then called ''forte and pia...

CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 45:29

- Updated: 23 May 2014

- views: 473100

- published: 23 May 2014

- views: 473100

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi Savall

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 71:09

- Updated: 17 Jan 2014

- views: 414581

- published: 17 Jan 2014

- views: 414581

The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:22

- Updated: 03 Aug 2011

- views: 25551256

- published: 03 Aug 2011

- views: 25551256

Harald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin Test

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 42:48

- Updated: 02 Jan 2016

- views: 4250

- published: 02 Jan 2016

- views: 4250

J. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. Harnoncourt

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 46:32

- Updated: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 27032

- published: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 27032

Die Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 25:45

- Updated: 16 Jan 2013

- views: 50886

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 23:39

- Updated: 16 Jan 2015

- views: 7672

- published: 16 Jan 2015

- views: 7672

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 38:30

- Updated: 05 Mar 2015

- views: 3336

- published: 05 Mar 2015

- views: 3336

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald Kuijken

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 52:18

- Updated: 05 Mar 2014

- views: 31998

- published: 05 Mar 2014

- views: 31998

J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 72:01

- Updated: 16 Jan 2014

- views: 22117

- published: 16 Jan 2014

- views: 22117

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:21

- Updated: 27 May 2016

- views: 133

- published: 27 May 2016

- views: 133

Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 12:36

- Updated: 24 Jan 2015

- views: 1093

- published: 24 Jan 2015

- views: 1093

- Playlist

- Chat

- Playlist

- Chat

CID - Painting Ki Chori - Episode 1079 - 23rd May 2014

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 May 2014

- views: 473100

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Jordi Savall

- Report rights infringement

- published: 17 Jan 2014

- views: 414581

The Smashing Pumpkins - 1979

- Report rights infringement

- published: 03 Aug 2011

- views: 25551256

Harald Schmidt Show 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams / Cholesterin Test

- Report rights infringement

- published: 02 Jan 2016

- views: 4250

J. S. Bach - Musikalisches Opfer (Ofrenda Musical) : BWV 1079 - N. Harnoncourt

- Report rights infringement

- published: 23 Feb 2013

- views: 27032

Die Harald Schmidt Show - Folge 1079 - Kühlschränke des Teams

- Report rights infringement

- published: 16 Jan 2013

- views: 50886

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Brisbane to Maryborough - 15/01/2015

- Report rights infringement

- published: 16 Jan 2015

- views: 7672

BB18 ¼ 1079 - QR 150th Steam Train - Cairns to Kuranda - 16/02/2015

- Report rights infringement

- published: 05 Mar 2015

- views: 3336

Bach: The musical offering, BWV 1079 | Sigiswald Kuijken

- Report rights infringement

- published: 05 Mar 2014

- views: 31998

J.S. Bach: Musikalisches Opfer BWV 1079 [Le Concert des Nations - J.Savall]

- Report rights infringement

- published: 16 Jan 2014

- views: 22117

BEST ENGINE SOUNDS Couple of TAKEOFFS from AVIANO ITALIAN Airbase - CODE 1079

- Report rights infringement

- published: 27 May 2016

- views: 133

Charles Rosen plays Bach 2 Ricercars from The Musical Offering BWV 1079

- Report rights infringement

- published: 24 Jan 2015

- views: 1093

Real Madrid wins Champions League in penalty shootout

Edit Deseret News 29 May 2016'Mass rape' video on social media shocks Brazil

Edit BBC News 27 May 2016Putin blasts West on first trip to EU country this year

Edit St Louis Post-Dispatch 28 May 2016Brazil police identify 4 of 30-plus men wanted in gang rape

Edit One India 28 May 2016It’s Game On for Sanders and Trump but Game Over for Hillary

Edit WorldNews.com 27 May 2016Peak Files 2016 First Quarter Results and Operating Highlights

Edit Stockhouse 28 May 2016Peak depose ses resultats et faits saillants du 1er trimestre 2016

Edit Stockhouse 28 May 2016Two Sacramento teens killed in crash on Power Inn Road

Edit Sacramento Bee 27 May 2016NACHC Launches New Advocacy Initiative (NACHC - National Association of Community Health Centers)

Edit Public Technologies 27 May 2016JA Solar Announces First Quarter 2016 Results (JA Solar Holdings Co Ltd)

Edit Public Technologies 27 May 2016CHP, deputies recover 22 stolen vehicles in rural El Dorado County

Edit Sacramento Bee 26 May 2016Missing girl last seen bleeding and in distress in Solano County

Edit Sacramento Bee 26 May 2016Sacramento father and toddler daughter missing for days

Edit Sacramento Bee 26 May 2016A 20-degree rise in temperatures in Sacramento this week

Edit Sacramento Bee 26 May 2016ReneSola to Participate at the 44th Cowen and Company Annual Technology, Media & Telecom Conference (ReneSola Ltd)

Edit Public Technologies 26 May 2016Watch: Mama bears and her cubs reluctantly scurry from Sierra garage

Edit Sacramento Bee 25 May 2016Roseville police arrest 3 men suspected of stealing from autos

Edit Sacramento Bee 25 May 2016MORTH bonanza for LDF govt.

Edit The Hindu 25 May 2016- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Next page »