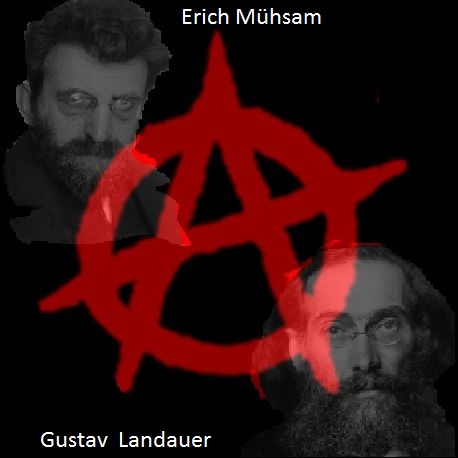

Gustav Landauer

One of the great influences on the German anarchist revolutionary, Erich Mühsam, was his friend and fellow anarchist, Gustav Landauer (1870-1919), murdered by government troops putting down the 1919 Bavarian Revolution, in which Landauer and Mühsam were both active participants. Mühsam shared Landauer’s rejection of the Marxist theory of historical materialism which saw socialism as the result of capitalist (over) development, instead insisting on the need for revolutionaries to make the revolution, for socialism is a process of creation, not the automatic result of technological development. In Volume One of Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, I included several excerpts from Landauer’s writings rejecting the Marxist view of history, as well as his famous critique of the state as “a relationship between human beings” which we destroy “by entering into other relationships, by behaving differently to one another” (Selection 49). Here I reproduce some further extracts from his 1911 book, Call to Socialism, in which Landauer expands on his critique of Marxism, arguing that an anarchist form of socialism may be possible in a variety of social circumstances, and that one does not have to wait “for the tidy progress of big capitalism” for anarchy and freedom to be achieved.

Against Marxism: For Anarchist Socialism

What Karl Marx called cooperation that is supposed to be an element of socialism is — the form of work which he saw in the capitalist enterprises of his time, the factory system, where thousands work in one room, the adaptation of the worker to the machines and the resulting pervasive division of labour in the production of commodities for the capitalist world market. For he says unquestioningly that capitalism is “already actually based on the social production enterprise”!

Yes indeed, such unparalleled nonsense goes against the grain, but it is certainly Karl Marx’s true opinion that capitalism develops socialism completely out of itself and that the socialist mode of production “flourishes” under capitalism. We already have cooperation, we already are at least well on the road to common ownership of the earth and the means of production. In the end nothing will be left to do but to chase away the few remaining owners. Everything else has blossomed from capitalism. For capitalism is equated with progress, society and even socialism. The true enemy is “the middle classes, the small industrialist, the small merchant, the craftsman, the farmer.” For they work, themselves, and have at most a few helpers and apprentices. That is the bungler, the dwarf enterprise, while capitalism is uniformity, the work of thousands in one place, work for the world market; that is social production and socialism.

That is Karl Marx’s true doctrine: when capitalism has gained complete victory over the remnants of the Middle Ages, progress is sealed and socialism is practically here.

It is not symbolically significant that the foundation of Marxism, the Bible of this sort of socialism is called Capital? We oppose this capitalist socialism with our own socialism, saying: socialism, culture and solidarity, just exchange and joyous work, the society of societies can come only when a spirit awakens such as the Christian and pre-Christian era of the Teutonic nations knew it, and when this spirit does away with the unculture, dissolution and decline, which in economic terms is called: capitalism.

Thus two opposite things stand in sharp contrast.

Here Marxism—there socialism!

Marxism—unspirit, the paper blossom on the beloved thornbush of capitalism.

Socialism — the new force against rottenness; the culture that rises against the combination of un-spirit, hardship, and violence, against the modern state and modern capitalism.

And now one can understand what I want to say to its face against this no less modern thing, Marxism: it is the plague of our time and the curse of the socialist movement. Now it will be said even more clearly that it is so, why it is so, and why socialism can come about only in mortal enmity toward Marxism.

Call to Socialism

For Marxism is, above all, the philistine who looks down upon and despises everything past, who calls whatever suits him the present or the beginning of the future, who believes in progress, who likes 1908 better than 1907, who expects something quite special from 1909, and almost a final eschatological miracle from something so far off as 1920.

Marxism is the philistine and therefore the friend of everything mass-like and comprehensive. Something like a medieval republic of cities or a village mark or a Russian mir or a Swiss Allmend or a communist colony cannot for him have the least similarity with socialism, but a broad, centralized state already resembles his state of the future quite closely. Show him a country at a period when the small peasants prosper, when highly skilled trades flourish, when there is little misery, he will contemptuously turn up his nose.

Karl Marx and his successors thought they could make no worse accusation against the greatest of all socialists, Proudhon, than to call him a petit-bourgeois and petit-peasant socialist, which was neither incorrect nor insulting, since Proudhon showed splendidly to the people of his nation and his time, predominantly small farmers and craftsmen, how they could have achieved socialism immediately without waiting for the tidy progress of big capitalism. However, believers in progress do not at all want to hear us speak of a possibility that was once there and yet did not become reality, and the Marxists and those infected by them cannot stand to hear anyone speak of a socialism that could have been possible before the downward movement which they call the upward movement of sacred capitalism.

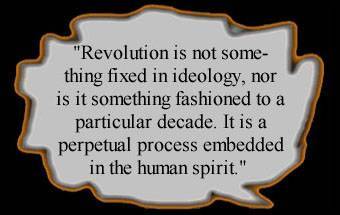

We, on the other hand, do not separate a fabulous development and social processes from what men want, do, could have wanted, and could have done. We know, however, that the determination and necessity of all that happens, including, of course, will and action, is valid and without exception, but only after the fact, i.e., after a reality is already there, does it thus become a necessity. When something did not happen, it was thus not possible, because, for example, men to whom urgent appeals were addressed and to whom reason was preached with fervour did not want to and could not be reasonable. Aha! the Marxists will interject triumphantly, Karl Marx however predicted that there was no possibility for that. Yes sir, we answer, and thereby he assumed a certain part of the guilt that it did not come about. He was for then, and for a long time afterwards, one of the guilty hinderers. In our opinion, human history does not consist of anonymous processes and a mere accumulation of many small mass events and omissions. For us bearers of history are persons, and for us there are also guilty persons.

Proudhon by Courbet

Does anyone believe that Proudhon did not, like every prophet, every herald, more strongly than any cold scientific observer, often in great hours sense the impossibility of leading these his people to what he considered the most beautiful and most natural possibility? Anyone who thinks that faith in fulfillment is part of the great deeds, visionary behaviour and urgent creativity of the apostles and leaders of mankind, knows them badly. Faith in their sacred truth is certainly a part of it, but also despair in men and the feeling of impossibility! Where overwhelming change and renewal have occurred, it is the impossible and incredible that is precisely the usual factor that brought about change.

But Marxism is uncultured, and it therefore always points, full of mockery and triumph, at failures and futile attempts and has such a childish fear of defeat. It shows greater contempt for nothing else than what it calls experiments or failures. It is a shameful sign of disgraceful decline, especially for the German people, whom such fear of idealism, enthusiasm and heroism so poorly fits, that such pitiful characters are the leaders of its enslaved masses. But the Marxists are for the impoverished masses exactly what nationalists have been since 1870 for the satiated classes of people: worshippers of success.

Thus we grasp another, more accurate meaning of the term “materialist conception of history.” Yes indeed, the Marxists are materialists in the ordinary, crude, popular sense of the word, and just like the nationalistic blockheads, they strive to reduce and exterminate idealism. What the nationalistic bourgeois has made of the German students, the Marxists have made of broad segments of the proletariat, cowardly little men without youth, wildness, courage, without joy in attempting anything, without sectarianism, without heresy, without originality and individuality. But we need all that. We need attempts. We need the expedition of a thousand men to Sicily. We need these precious Garibaldi-natures, and we need failures upon failures and the tough nature that is frightened by nothing, that holds firm and endures and starts over and over again until it succeeds, until we are through, until we are unconquerable. Whoever does not take upon himself the danger of defeat, of loneliness, of set-backs, will never attain victory.

One of Landauer’s Papers

O you Marxists, I know how bad that sounds in your ears, you who fear nothing except what you call stabs in the back. That word belongs to your special vocabulary and perhaps with some right, since you show the enemy your back more than your face. I know how deeply you hate and how repulsive and unpleasant your dry temperaments find such fiery natures as the constructive Proudhon and the destructive Bakunin or Garibaldi. Everything Latin or Celtic, everything that smacks of the open air and wildness and initiative is almost embarrassing to you. You have plagued yourselves enough to exclude everything free, personal or youthful, which you call stupidities, from the party, the movement and the masses.

Truly, things would be better for socialism and our people if instead of the systematic stupidity, which you call your science, we had the fiery-headed stupidities of hot-tempered men brimming over with enthusiasm, which you cannot stand. Yes indeed, we want to do what you call experiments. We want to make attempts. We want to create from the heart, and then we want, if it must be, to suffer shipwreck and bear defeat, until we have the victory and land is sighted. Ashen-faced, drowsy men, cynical and uncultured, are leading our people; where are the Columbus natures, who prefer to sail the high seas in a fragile ship into the unknown rather than wait for developments? Where are the young, joyous victorious Reds who will laugh at these gray faces? The Marxists don’t like to hear such words, such attacks, which they call relapses, such enthusiastic unscientific challenges. I know, and that is exactly why I feel so good at having told them this. The arguments I use against them are sound and they hold water, but if instead of refuting them with arguments I annoyed them to death with mockery and laughter, that would also suit me fine.

Thus the uncultured Marxist is much too clever, level-headed and cautious ever to think that capitalism in a state of total collapse, as was the case during the February [1848] revolution in France, might be confronted with socialist organization, just as he prefers to kill the forms of living community from the Middle Ages that were saved particularly in Germany, France, Switzerland, Russia, during centuries of decline and to drown them in capitalism rather than to recognize that they contain the seeds and living crystals of the coming socialist culture.

However if one shows him the economic conditions, say, of England from the middle of the nineteenth century, with its desolate factory system, with the depopulation of the countryside, the homogenization of the masses an of misery, with economies geared to the world market instead of to real needs, he finds social production, cooperation, the beginnings of common ownership. He feels at home…

Add to this, capitalist concentration which looked as if the number of capitalists and of fortunes would become ever fewer, and further the model of the omnipotent government in the centralized state of our times, and add finally the ever greater perfection of the industrial machines, the ever increased division of labour, the replacement of the trained craftsman by the unskilled machine operator — all this however seen in an exaggerated and caricatured light, for it all has another side and is never a schematically unilinear development. It is a struggle and equilibrium of various tendencies, but everything Marxism sees is always grotesquely simplified and caricatured. Add finally the hope that working hours will become shorter and shorter and human work more and more productive: then the state of the future is finished. The future state of the Marxists: the blossom on the tree of governmental, capitalist and technological centralization.

It must yet be added that the Marxist, when he dreams his pipe dreams especially boldly — for never was a dream emptier and drier, and if there ever have been unimaginative fantasists, the Marxists are the worst — the Marxist extends his centralism and economic bureaucracy beyond present-day states and advocates a world organization to regulate and direct the production and distribution of goods. That is Marxism’s internationalism. As formerly in the [First] International everything was supposed to be regulated and decided by the London-based General Council and today in Social Democracy [the “Second” International] all decisions are made in Berlin, this world production authority will someday look into every pot and will have the amount of grease for every machine listed in its ledger.

One more layer and our description of Marxism will be finished.

The forms of organization of what these people call socialism blossom forth completely in capitalism, except that these organizations, these ever expanding — through steam — factories are still in the hands of private entrepreneurs, exploiters. We have already seen, however, that they are supposed to be reduced to a smaller and smaller number by competition. One must visualize clearly what this means: first a hundred thousand — then a few thousand — then a few hundred — then some seventy or fifty — then a few absolutely monstrous giant entrepreneurs.

Opposed to them stand the workers, the proletarians. They become more and more numerous, the middle classes disappear, and with the number of workers the number, intensity and power of the machines also grows, so that not only the number of workers, but also the number of unemployed, the so-called industrial reserve-armies, increases. According to this description, capitalism reaches an impasse and the struggle against it, i.e., against the few remaining capitalists, becomes easier and easier for the countless masses of disinherited who have an interest in change. Thus it must be remembered that in Marxist doctrine everything is immanent, though the term is taken from another area and misapplied. Here it means that nothing requires special efforts or mental insights, everything follows smoothly from the social process. The so-called socialist forms of organization are already immanent in capitalism…

As the program of German Social Democracy says in such beautiful and so genuinely Marxist terms (otherwise various ungenuine elements have crept in, which the makers of this program now are calling revisionist in their opponents): the powers of production are growing beyond the capacity of contemporary society. This contains the genuinely Marxist teaching that in contemporary society the forms of production have become more and more socialist and that these forms lack only the right form of ownership. They call it social ownership, but when they call the capitalist factory system a [system of] social production (not only Marx does this in Capital, but the present-day Social Democrats in their currently effective program call work in the forms of present-day capitalism, social work), we know the real implications of their socialist forms of labour.

Just as they consider the production forms of steam technology in capitalism to be a socialist form of labour, so they consider the centralized state to be the social organization of society and bureaucratically administered state-property to be common property! These people really have no instinct for the meaning of society. They haven’t the least idea that society can only be a society of societies, only a federation, only freedom. They therefore do not know that socialism is anarchy and federation. They believe socialism is government, while others who thirst for culture want to create socialism because they want to escape from the disintegration and misery of capitalism and its concomitant poverty, spiritlessness and coercion, which is only the other side of economic individualism. In short, they want to escape from the state into a society of societies and voluntary association.

Because, as these Marxists say, socialism is still so to speak, the private property of the entrepreneurs, who produce wildly and senselessly, and since they are in possession of the socialist production powers (read: of steam power, perfected production machinery and the superfluously available proletarian masses), that is, because this situation is like a magic broomstick in the hands of the sorcerer’s apprentice, a deluge of goods, overproduction and confusion must be the result, i.e., crises must ensue, which, no matter what the details may be, always come about, at least in the opinion of the Marxists, because the regulative function of a statistically controlling and directing world state authority is necessary to go with the socialist mode of production, which, in their wickedly stupid view, already exists.

As long as this controlling authority is missing, “socialism” is still imperfect, and disorder must result. The forms of organization of capitalism are good, but they lack order, discipline, and strict centralization. Capitalism and government must come together, and where we would speak of state capitalism, those Marxists say that socialism is here. But just as their socialism contains all forms of capitalism and regimentation, and just as they allow the tendency to uniformity and leveling that exists today to progress to its ultimate perfection, the proletarian too is carried over into their socialism. The proletarian of the capitalist enterprise has become the state proletarian, and proletarianization has, when this type of socialism begins, really and predictably reached gigantic proportions. Everyone without exception is an employee of the state.

Capitalism and the state must come together—that is in truth Marxism’s ideal. Although they do not want to hear of their ideal, we see they seek to promote this trend of development. They do not see that the tremendous power and bureaucratic desolation of the state is necessary only because our communal life has lost the spirit, because justice and love, the economic associations and the blossoming multiplicity of small social organisms have vanished. They see nothing of all this deep decay of our times; they hallucinate progress.

Technology progresses, of course. It actually does so in many times of culture, although not always—there are also cultures without technical progress. It progresses especially in times of decay, of the individualization of spirit and the atomization of the masses. That is precisely our point. The real progress of technology together with the real baseness of the time is—to speak, for once, Marxistically for the Marxists — the real, material basis for the ideological superstructure, namely for the Marxists’ Utopia of progressive socialism…

No doubt, the Marxists believe that if the front and back sides of our degradation, the capitalist conditions of production and the state, were brought together, then their progress and development would have reached its goal and so justice and equality would be established. Their comprehensive economic state, whether it be the heir to previous states or their world state, is a republican and democratic structure, and they really believe that the laws of such a state would provide for the welfare of all the common people, since they comprise the state. Here we must be allowed to burst out in irrepressible laughter at this most pitiful of all stodgy fantasies. Such a complete mirror image of the Utopia of the sated bourgeois can in fact only be the product of the undisturbed laboratory development of capitalism. We will waste no more time on this accomplished ideal of the era of decline and of depersonalized unculture, this government of dwarves.

We will see that true culture is not empty but fulfilled and that the true society is a multiplicity of real, small affinities that grow out of the binding qualities of individuals, out of the spirit, a structure of communities, and a union. This “socialism” of the Marxists is a gigantic goiter that supposedly will develop. Never fear, we will soon see that it will not develop. Our socialism, however, should grow in the hearts of men. It wishes to cause the hearts of those who belong together to grow in unity and spirit. The alternative is not pigmy-socialism or socialism of the spirit, for we will soon see that if the masses follow the Marxists or even the revisionists, then capitalism will remain. It absolutely does not tend to change suddenly into the “socialism” of the Marxists nor to develop into the socialism of the revisionists, which can be thus called only with a shy voice. Decline—in our case, capitalism— has in our time just as much vitality as culture and expansion had in other times. Decline does not at all mean decrepitude, a tendency toward collapse or drastic reversal. Decline, the Epoch of sunkenness, folklessness, spiritlessness, is capable of lasting for centuries or millennia. Decline, in our case, capitalism, possesses in our time precisely that measure of vitality which is not found in contemporary culture and expansion. It has as much strength and energy as we fail to muster for socialism. The choice we face is not: one form of socialism, or the other, but simply: capitalism or socialism; the state or society; unspirit or spirit. The doctrine of Marxism does not lead out of capitalism. Nor is there any truth to Marxism’s doctrine that capitalism can at times out-trump Baron Münchhausen’s fantastic accomplishment of pulling himself out of a strange swamp by his pig-tail, i.e., the prophecy that capitalism will emerge out of its own swamp by virtue of its own development.

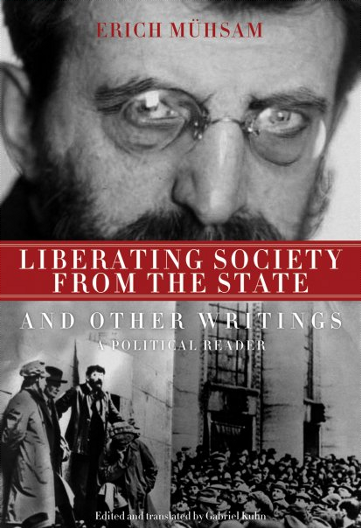

Gustav Landauer, 1911

Published by PM Press