- Order:

- Duration: 10:49

- Published: 12 May 2009

- Uploaded: 20 Jul 2011

- Author: musissima

| Name | Front de libération du Québec |

|---|---|

| Logo | Bandera FLQ.svg|thumb|Flag |

| Dates | 1963–1970 |

| Motives | Creation of an independent socialist Quebec state, economic nationalism |area = Quebec |

| Status | Inactive (disbanded)}} |

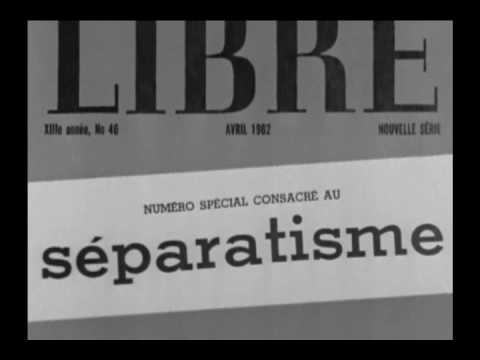

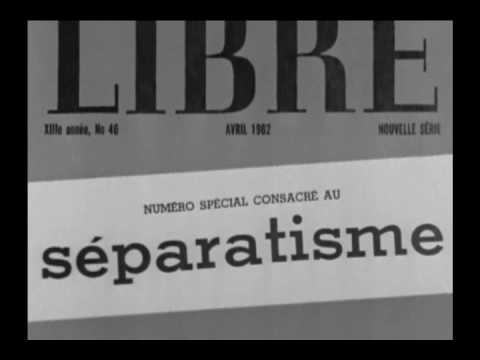

The Front de libération du Québec (FLQ; ) was a left-wing nationalist and socialist paramilitary group in Quebec, Canada, active between 1963 and 1970, which is regarded as a terrorist organization due to its violent methods of action. It was responsible for over 160 violent incidents which killed eight people and injured many more, including the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange in 1969. These attacks culminated in 1970 with what is known as the October Crisis, in which British Trade Commissioner James Cross was kidnapped and Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte was murdered by strangulation. Founded in the early 1960s, it supported the Quebec sovereignty movement.

FLQ members practised propaganda of the deed and issued declarations that called for a socialist insurrection against oppressors identified with "Anglo-Saxon" imperialism, The FLQ was a loose association operating as a clandestine cell system. Various cells emerged over time: the Viger Cell founded by Robert Comeau, history professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal; the Dieppe Cell; the Louis Riel Cell; the Nelson Cell; the Saint-Denis Cell; the Liberation Cell; and the Chénier Cell. The last two of these cells were involved in what became known as the October Crisis. From 1963 to 1970, the FLQ committed more than 200 violent actions, including bombings, bank hold-ups, kidnappings, at least three killings by FLQ bombs and two killings by gunfire. In 1966 Revolutionary Strategy and the Role of the Avant-Garde was prepared by the FLQ, outlining their long term strategy of successive waves of robberies, violence, bombings, and kidnappings, culminating in revolution. The history of the FLQ is sometimes described as a series of "waves".

By June 1, 1963, this original group had been arrested. In 1963, Gabriel Hudon and Raymond Villeneuve were sentenced to 12 years in prison after their bomb killed Wilfred O'Neill, a watchman at Montreal's Canadian Army Recruitment Centre. Their targets also included English-owned businesses, banks, McGill University, Loyola College.

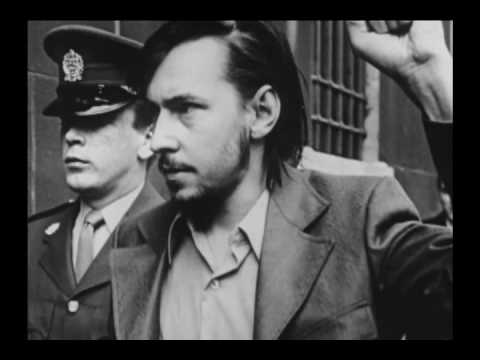

By August 1966, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) had arrested many FLQ members. Gagnon and Vallières had fled to the United States, where they protested in front of the United Nations and were later arrested. It was during his incarceration that Vallières wrote his book White Niggers of America. In September 1967, the pair were extradited to Canada.

In 1968, after various riots within Quebec and in Europe, a new group of FLQ was formed. Within a year, this group of Felquistes had exploded 52 bombs. Rather than La Cognée, they wrote La Victoire, or Victory. The various members of the group were arrested by May 2, 1969.

1969 also saw many riots, including one against McGill University. The RCMP had intercepted intelligence relating to the planned riots, and prevented excessive damage. This failed riot led to Mario Bachand leaving Canada, and another group of FLQ forming, which would become responsible for the October Crisis. This group, formed of Paul Rose, Jacques Rose, Francis Simard, and Nigel Hamer became known as the "South Shore Gang".

During the police strike of 1969, the "Taxi Liberation Front", a creation of the "Popular Liberation Front", which was itself the creation of Jacques Lanctôt and Marc Carbonneau, killed a police officer. Jacques Lanctôt is credited by Michael McLoughlin, author of Last Stop, Paris: The Assassination of Mario Bachand and the Death of the FLQ, with writing the FLQ Manifesto during the prelude to the October Crisis.

The South Shore Gang bought a house, which they named "The Little Free Quebec", and it quickly became a den of the FLQ. Jacques Lanctôt was charged in connection with a failed FLQ kidnapping attempt of an Israeli diplomat, and in 1970, while a member of the FLQ, likely took refuge at "The Little Free Quebec". These new FLQ members bought two other houses, prepared their plans, and stocked sufficient equipment for their upcoming actions.

The group split into two over what plans should be taken, but were reunited during the crisis itself.

The FLQ also stipulated how the above demands would be carried out: #the prisoners were to be taken to the Montreal airport and supplied a copy of the FLQ Manifesto. They were to be allowed to communicate with each other and become familiar with the Manifesto. #they were not to be dealt with in a harsh or brutal manner. #they must be able to communicate with their lawyers to discuss the best course of action, whether to leave Quebec or not. As well, these lawyers must receive passage back to Quebec.

As part of its Manifesto, the FLQ stated: "In the coming year Bourassa (Quebec premier Robert Bourassa) will have to face reality; 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized."

Canada's Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, in his statement to the press during the October Crisis, admitted that the radicalism occurring in Quebec at this time had bred out of social unease due to imperfect legislation. “The government has pledged that it will introduce legislation which deals not only with the symptoms but with the social causes which often underlie or serve as an excuse for crime and disorder.” (Pierre Trudeau, CBC interview). However, despite this admission, Trudeau declared in his statement to the press that in order to deal with the unruly radicals or "revolutionaries," the federal government would invoke the War Measures Act, the only time the country used these powers during peacetime. Invoking the War Measures Act was a risky move for Trudeau because the act overrides fundamental rights and privileges enumerated in the Canadian Bill of Rights; therefore, there was a strong possibility that Trudeau might have lost popular support among Quebec voters; however, this did not occur.

In an impromptu interview with Tim Ralfe and Peter Reilly on the steps of Parliament, Pierre Trudeau, responding to a question of how extreme his implementation of the War Measures Act would be, Trudeau answered, “Well, just watch me.” This line has become a part of Trudeau’s legacy.

Early in December 1970, police discovered the location of the kidnappers holding James Cross. His release was negotiated and on December 3, 1970, five of the terrorists were granted their request for safe passage to Cuba by the Government of Canada after approval by Fidel Castro.

As a result of the invocation of the War Measures Act, civil liberties were suspended. By December 29, 1970, police had arrested 453 persons with suspected ties to the FLQ. Some detainees were released within hours, while others were held for up to 21 days. Several persons who were detained were initially denied access to legal counsel. Of the 453 people who were arrested, 435 were eventually released without ever being charged.

On December 13, 1970, Pierre Vallières announced in Le Journal that he had terminated his association with the FLQ. As well, Vallières renounced the use of terrorism as a means of political reform and instead advocated the use of standard political action.

In July 1980, police arrested and charged a sixth person in connection with the Cross kidnapping. Nigel Barry Hamer, a British radical socialist and FLQ sympathizer, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 months in jail.

In late December, four weeks after, the kidnappers of James Cross were found. Paul Rose and the kidnappers and murderers of Pierre Laporte were found hiding in a country farmhouse. They were tried and convicted for kidnapping and murder.

The events of October 1970 contributed to the loss of support for violent means to attain Quebec independence, and increased support for a political party, the Parti Québécois, which took power in 1976.

The support and political capacity of the FLQ changed drastically during the 1970s. The FLQ immediately lost public support after the October crisis and the murder of Laporte. The general public overwhelmingly supported the emergency powers and the presence of the military in Quebec. The Parti Québécois warned young activists against joining “childish cells in a fruitless revolutionary adventurism which might cost them their future and even their lives.” Laporte’s murder marked a crossroad in the political history of the FLQ. It helped sway public opinion towards more conventional forms of political participation and drove up popular support for the Parti Québécois.

The rise of the PQ attracted both active and would be participants away from the dangerous activities of the FLQ. In December 1971, Pierre Vallières emerged after three years in hiding to announce that he was joining the PQ. In justifying his decisions he said that the FLQ was a “shock group” whose continued activities would only play into the hands of the forces of repression against which they were no match. Those members of the FLQ who had fled began returning to Canada in late 1971 continuing to 1982 and most were given light sentences for their terrorist offences.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.