- Order:

- Duration: 8:00

- Published: 06 Dec 2009

- Uploaded: 27 May 2011

- Author: SisyphusRedeemed

![Zeitgeist: Addendum - ENG MultiSub [FULL MOVIE] Zeitgeist: Addendum - ENG MultiSub [FULL MOVIE]](http://web.archive.org./web/20110602035549im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/gmIYMMYDXK8/0.jpg)

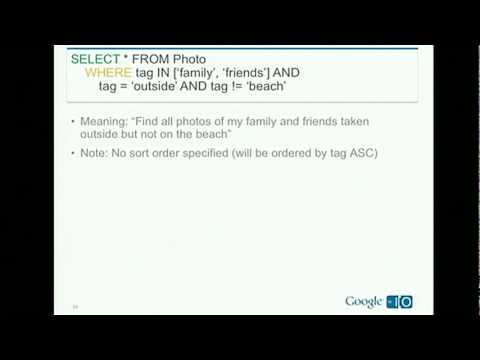

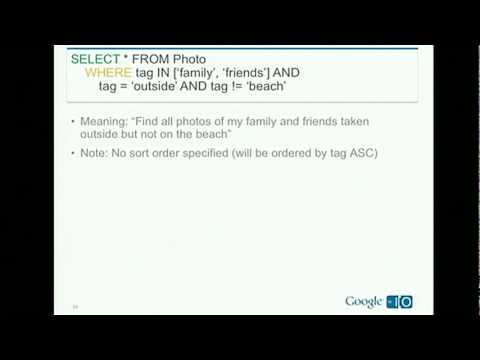

Multi-valued logics are intended to preserve the property of designationhood (or being designated). Since there are more than two truth values, rules of inference may be intended to preserve more than just whichever corresponds (in the relevant sense) to truth. For example, in a three-valued logic, sometimes the two greatest truth-values (when they are represented as e.g. positive integers) are designated and the rules of inference preserve these values. Precisely, a valid argument will be such that the value of the premises taken jointly will always be less than or equal to the conclusion.

For example, the preserved property could be justification, the foundational concept of intuitionistic logic. Thus, a proposition is not true or false; instead, it is justified or flawed. A key difference between justification and truth, in this case, is that the law of excluded middle doesn't hold: a proposition that is not flawed is not necessarily justified; instead, it's only not proven that it's flawed. The key difference is the determinacy of the preserved property: One may prove that P is justified, that P is flawed, or be unable to prove either. A valid argument preserves justification across transformations, so a proposition derived from justified propositions is still justified. However, there are proofs in classical logic that depend upon the law of excluded middle; since that law is not usable under this scheme, there are propositions that cannot be proven that way.

Another example of an infinitely-valued logic is probability logic.

The 20th century brought the idea of multi-valued logic back. The Polish logician and philosopher Jan Łukasiewicz began to create systems of many-valued logic in 1920, using a third value "possible" to deal with Aristotle's paradox of the sea battle. Meanwhile, the American mathematician Emil L. Post (1921) also introduced the formulation of additional truth degrees with n ≥ 2,where n are the truth values. Later Jan Łukasiewicz and Alfred Tarski together formulated a logic on n truth values where n ≥ 2 and in 1932 Hans Reichenbach formulated a logic of many truth values where n→infinity. Kurt Gödel in 1932 showed that intuitionistic logic is not a finitely-many valued logic, and defined a system of Gödel logics intermediate between classical and intuitionistic logic; such logics are known as intermediate logics.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Matt Dillahunty |

|---|---|

| Caption | Matt Dillahunty on The Atheist Experience TV show, 25th July 2006. |

| Birth date | March 31, 1969 |

| Death date | |

| Known for | Atheist activism |

| Nationality |

Matt Dillahunty is the president of the Atheist Community of Austin, and is also a host of the live internet radio show "Non-Prophets Radio" and of the Austin cable access show "The Atheist Experience". Matt was raised as a fundamentalist Baptist Christian, and sought to become a Baptist minister. His religious studies, instead of bolstering his faith as he intended, led to a complete rejection of Christianity. He now continues to study philosophy, religion, science, and history, while attempting to educate people about atheism and religion, and "to prevent others from wasting another day on irrational beliefs". Dillahunty also served in the armed forces during the Gulf War and was also in the Armed forces in Haiti during the early 1990s.

The show of which he is one of the hosts, "The Atheist Experience", has become popular on YouTube and is consistently on the top discussed and top rated pages. He is also the founder and contributor of a counter-apologetics encyclopedia at Iron Chariots and its subsidiary sites.

Category:Living people Category:American atheists Category:Atheism activists Category:1969 births Category:United States Navy sailors Category:Former Baptists

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | George Washington |

|---|---|

| Nationality | American |

| Order | 1st President of the United States |

| Term start | April 30, 1789 |

| Term end | March 4, 1797 |

| Vicepresident | John Adams |

| Predecessor | Office created |

| Successor | John Adams |

| Order2 | 1st Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army |

| Term start2 | June 15, 1775 |

| Term end2 | December 23, 1783 |

| Appointer2 | Continental Congress |

| Successor2 | Henry Knox |

| Term start3 | July 13, 1798 |

| Term end3 | December 14, 1799 |

| President3 | John Adams |

| Predecessor3 | James Wilkinson |

| Successor3 | Alexander Hamilton |

| Birth date | February 22, 1732 |

| Birth place | Westmoreland County, Colony of Virginia |

| Death date | December 14, 1799 |

| Death place | Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Restingplace | Washington family vault,Mount Vernon |

| Nationality | AmericanBritish subject (prior to 1776) |

| Party | None |

| Spouse | Martha Dandridge Custis Washington |

| Children | none |

| Religion | Church of EnglandEpiscopal |

| Occupation | Farmer (planter) soldier (officer) |

| Signature | George Washington signature.svg |

| Signature alt | Cursive signature in ink |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Virginia provincial militiaContinental ArmyUnited States Army |

| Serviceyears | militia: 1752–1758Continental Army: 1775–1783U. S. Army: 1798–1799 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General General of the Armies of the United States (posthumously in 1976) |

| Commands | Colony of Virginia's provincial regimentContinental ArmyUnited States Army |

| Battles | French and Indian War |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal, Thanks of Congress |

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1797, leading the American victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander in chief of the Continental Army, 1775–1783, and presiding over the writing of the Constitution in 1787. As the unanimous choice to serve as the first President of the United States (1789–1797), he developed the forms and rituals of government that have been used ever since, such as using a cabinet system and delivering an inaugural address. The president built a strong, well-financed national government that avoided war, suppressed rebellion and won acceptance among Americans of all types. Acclaimed ever since as the "Father of his country", Washington, along with Abraham Lincoln, has become a central icon of republican values, self sacrifice in the name of the nation, American nationalism and the ideal union of civic and military leadership.

In Colonial Virginia Washington was born into the provincial gentry in a wealthy, well connected family that owned tobacco plantations using slave labor. Washington was home schooled by his father and older brother but both died young and Washington became attached to the powerful Fairfax clan. They promoted his career as surveyor and soldier. Strong, brave, eager for combat and a natural leader, young Washington quickly became a senior officer of the colonial forces, 1754–58, during the first stages of the French and Indian War. Indeed his rash actions helped precipitate the war. Washington's experience, his military bearing, his leadership of the Patriot cause in Virginia, and his political base in the largest colony made him the obvious choice of the Second Continental Congress in 1775 as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army to fight the British in the American Revolution. He forced the British out of Boston in 1776, but was defeated and nearly captured later that year when he lost New York City. After crossing the Delaware River in the dead of winter he defeated the enemy in two battles, retook New Jersey, and restored momentum to the Patriot cause. Because of his strategy, Revolutionary forces captured two major British armies at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. Negotiating with Congress, governors, and French allies, he held together a tenuous army and a fragile nation amid the threats of disintegration and invasion. Historians give the commander in chief high marks for his selection and supervision of his generals, his encouragement of morale, his coordination with the state governors and state militia units, his relations with Congress, and his attention to supplies, logistics, and training. In battle, however, Washington was repeatedly outmaneuvered by British generals with larger armies. Washington is given full credit for the strategies that forced the British evacuation of Boston in 1776 and the surrender at Yorktown in 1781. After victory was finalized in 1783, Washington resigned rather than seize power, and returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon, provong his opposition to dictatorship and his commitment to republican government.

Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the United States Constitution in 1787 because of his dissatisfaction with the weaknesses of Articles of Confederation that had time and again impeded the war effort. Washington became the first President of the United States in 1789. He attempted to bring rival factions together in order to create a more unified nation. He supported Alexander Hamilton's programs to pay off all the state and national debts, implement an effective tax system, and create a national bank, despite opposition from Thomas Jefferson. Washington proclaimed the U.S. neutral in the wars raging in Europe after 1793. He avoided war with Britain and guaranteed a decade of peace and profitable trade by securing the Jay Treaty in 1795, despite intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs. Washington's "Farewell Address" was an influential primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against partisanship, sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars.

Washington had a vision of a great and powerful nation that would be built on republican lines using federal power. He sought to use the national government to improve the infrastructure, open the western lands, create a national university, promote commerce, found a capital city (later named Washington, D.C.), reduce regional tensions and promote a spirit of nationalism. "The name of AMERICAN," he said, must override any local attachments." At his death Washington was hailed as "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen". The Federalists made him the symbol of their party, but for many years the Jeffersonians continued to distrust his influence and delayed building the Washington Monument. As the leader of the first successful revolution against a colonial empire in world history, Washington became an international icon for liberation and nationalism. His symbolism especially resonated in France and Latin America. Historical scholars consistently rank him as one of the two or three greatest presidents.

Washington was the first-born child from his father's marriage to Mary Ball Washington. Six of his siblings reached maturity including two older half-brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, from his father's first marriage to Jane Butler Washington and four full-siblings, Samuel, Elizabeth(Betty), John Augustine and Charles. Three siblings died before becoming adults: his full-sister Mildred died when she was about one, and two half-siblings Butler and Jane died in their teens. George's father died when George was 11 years old, after which George's half-brother Lawrence became a surrogate father and role model. William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law and cousin of Virginia's largest landowner, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, was also a formative influence. Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County near Fredericksburg. Lawrence Washington inherited another family property from his father, a plantation on the Potomac River which he later named Mount Vernon. George inherited Ferry Farm upon his father's death, and eventually acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence's death.

The death of his father prevented Washington from crossing the Atlantic to receive an education at England's Appleby School, as his older brothers had done. He attended school in Fredericksburg until age 15. Talk of securing an appointment in the Royal Navy was dropped when his mother learned how hard that would be on him. Late in life, Washington was somewhat self-conscious that he was less educated than those of his contemporaries who had attended college. Thanks to Lawrence's connection to the powerful Fairfax family, at age 17 George was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County in 1749, a well-paid position which enabled him to purchase land in the Shenandoah Valley, the first of his many land acquisitions in western Virginia. Thanks also to Lawrence's involvement in the Ohio Company, a land investment company funded by Virginia investors, and Lawrence's position as commander of the Virginia militia, George came to the notice of the new lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Washington was hard to miss: at about six feet two inches (188 cm; estimates of his height vary), he towered over most of his contemporaries.

In 1751, Washington traveled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was suffering from tuberculosis, with the hope that the climate would be beneficial to Lawrence's health. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred, but immunized him against future exposures to the dreaded disease. Lawrence's health did not improve: he returned to Mount Vernon, where he died in 1752. Lawrence's position as Adjutant General (militia leader) of Virginia was divided into four offices after his death. Washington was appointed by Governor Dinwiddie as one of the four district adjutants in February 1753, with the rank of major in the Virginia militia. Washington also joined the Freemasons in Fredericksburg at this time.

Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio Country to protect an Ohio Company group building a fort at present-day Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. Before he reached the area, a French force drove out the company's crew and began construction of Fort Duquesne. With Mingo allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and some of his militia unit ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville; Jumonville was killed. The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754. He was allowed to return with his troops to Virginia. The episode demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience and impetuosity. These events had international consequences; the French accused Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission similar to Washington's 1753 mission. Both France and Britain responded by sending troops to North America in 1755, although war was not formally declared until 1756.

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly fire episode in which his unit and another British unit thought the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with 14 dead and 26 wounded in the mishap. In the end there was no real fighting for the French abandoned the fort and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley. Mission accomplished, Washington retired from his Virginia Regiment commission in December, 1758, and did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.

On January 6, 1759, Washington married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis. Surviving letters suggest that he may have been in love at the time with Sally Fairfax, the wife of a friend. Nevertheless, George and Martha made a compatible marriage, because Martha was intelligent, gracious, and experienced in managing a slave plantation. Together the two raised her two children from her previous marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy" by the family. Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together — his earlier bout with smallpox in 1751 may have made him sterile. Washington, himself, an extraordinary athlete, proudly may not have been able to admit to his own sterility while privately he grieved over not having his own children. The newly wed couple moved to Mount Vernon, near Alexandria, where he took up the life of a planter and political figure.

Washington's marriage to Martha greatly increased his property holdings and social standing, and made him one of Virginia's wealthiest men. He acquired one-third of the 18,000 acre (73 km²) Custis estate upon his marriage, worth approximately $100,000, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children, for whom he sincerely cared. He frequently bought additional land in his own name and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to , and had increased the slave population there to more than 100 persons. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.

after his marriage]]

Washington lived an aristocratic lifestyle—fox hunting was a favorite leisure activity. He also enjoyed going to dances and parties, in addition to the theater, races, and cock fights. Washington also was known to play cards, backgammon, and billiards. Like most Virginia planters, he imported luxuries and other goods from England and paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop. Extravagant spending and the unpredictability of the tobacco market meant that many Virginia planters of Washington's day were losing money. (Thomas Jefferson, for example, would die deeply in debt.)

Washington began to pull himself out of debt by diversifying his business interests and paying more attention to his affairs. By 1766, he had switched Mount Vernon's primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, a crop that could be sold in America, and diversified operations to include flour milling, fishing, horse breeding, spinning, and weaving. Patsy Custis's death in 1773 from epilepsy enabled Washington to pay off his British creditors, since half of her inheritance passed to him.

A successful planter, he was a leader in the social elite in Virginia. From 1768 to 1775, he invited some 2000 guests to his Mount Vernon estate, mostly those he considered "people of rank." As for people not of high social status, his advice was to "treat them civilly" but "keep them at a proper distance, for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority.". In 1769 he became more politically active, presenting the Virginia Assembly with legislation to ban the importation of goods from Great Britain.

Washington had three roles during the war. In 1775-77, and again in 1781 he led his men against the main British forces. He lost many of his battles—save the last one—but always survived to fight another day. He plotted the overall strategy of the war, in cooperation with Congress.

Second, he was charged with organizing and training the army. He recruited regulars and assigned General von Steuben, a German professional, to train them. He was not in charge of supplies, which were always short, but kept pressuring Congress and the states to provide essentials. Washington had the major voice in selecting generals for command, and in planning their basic strategy. His achievements were mixed, as some of his favorites (like John Sullivan) never mastered the art of command. Eventually he found men who got the job done, like General Nathaniel Greene, and his chief-of-staff Alexander Hamilton. The American officers never equaled their opponents in tactics and maneuver, and consequently they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes, at Saratoga and Yorktown, came from trapping the British far from base with much larger numbers of troops.

Third, and most important, Washington was the embodiment of armed resistance to the Crown—the representative man of the Revolution. His enormous stature and political skills kept Congress, the army, the French, the militias, and the states all pointed toward a common goal. By voluntarily stepping down and disbanding his army when the war was won, he permanently established the principle of civilian supremacy in military affairs. And yet his constant reiteration of the point that well-disciplined professional soldiers counted for twice as much as erratic amateurs helped overcome the ideological distrust of a standing army.

Although highly disparaging toward most of the Patriots, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. These articles were bold, as Washington was enemy general who commanded an army in a cause that many Britons believed would ruin the empire.

Historians debate whether or not Washington preferred a Fabian strategy to harass the British, with quick shark attacks followed by a retreat so the larger British army could not catch him, or whether he preferred to fight major battles. While his southern commander Greene in 1780-81 did use Fabian tactics, Washington, only did so in fall 1776 to spring 1777, after losing New York City and seeing much of his army melt away. Trenton and Princeton were Fabian examples. By summer 1777, however, Washington had rebuilt his strength and his confidence and stopped using raids and went for large-scale confrontations, as at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and Yorktown.

of Washington resigning his commission as commander-in-chief]]

By the Treaty of Paris (signed that September), Great Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers.

On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession. At Fraunces Tavern on December 4, Washington formally bade his officers farewell and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief. Historian Gordon Wood concludes that the greatest act in his life was his resignation as commander of the armies—an act that stunned aristocratic Europe. King George III called Washington the "the greatest character of the age" because of this.

The 1st United States Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however, he ultimately accepted the payment, to avoid setting a precedent whereby the presidency would be perceived as limited only to independently wealthy individuals who could serve without any salary. The president, aware that everything he did set a precedent, attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested.

Washington proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he talked regularly with department heads and listened to their advice before making a final decision. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."

Washington reluctantly served a second term as president. He refused to run for a third, establishing the customary policy of a maximum of two terms for a president.

The Residence Act of 1790, which Washington signed, authorized the President to select the specific location of the permanent seat of the government, which would be located along the Potomac River. The Act authorized the President to appoint three commissioners to survey and acquire property for this seat. Washington personally oversaw this effort throughout his term in office. In 1791, the commissioners named the permanent seat of government "The City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia" to honor Washington. In 1800, the Territory of Columbia became the District of Columbia when the federal government moved to the site according to the provisions of the Residence Act.

In 1791, Congress imposed an excise on distilled spirits, which led to protests in frontier districts, especially Pennsylvania. By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale defiance of federal authority known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The federal army was too small to be used, so Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and several other states. The governors sent the troops and Washington took command, marching into the rebellious districts. The rebels dispersed and there was no fighting, as Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.

In spring 1793 a major war broke out between conservative Britain and its allies and revolutionary France, launching an era of large-scale warfare that engulfed Europe until 1815. Washington, with cabinet approval, proclaimed American neutrality. The revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt was welcomed with great enthusiasm and propagandized the case for France in the French war against Britain, and for this purpose promoted a network of new Democratic Societies in major cities. He issued French letters of marque and reprisal to French ships manned by American sailors so they could capture British merchant ships. Washington demanded the French government recall Genêt, and denounced the societies.

Hamilton and Washington designed the Jay Treaty to normalize trade relations with Britain, remove them from western forts, and resolve financial debts left over from the Revolution. John Jay negotiated and signed the treaty on November 19, 1794. The Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington's strong support mobilized public opinion and proved decisive in securing ratification in the Senate by the necessary two-thirds majority. The British agreed to depart from their forts around the Great Lakes, subsequently the U.S.-Canadian boundary had to be re-adjusted, numerous pre-Revolutionary debts were liquidated, and the British opened their West Indies colonies to American trade. Most importantly, the treaty delayed war with Britain and instead brought a decade of prosperous trade with Britain. The treaty angered the French and became a central issue in many political debates.

Washington's public political address warned against foreign influence in domestic affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warned against bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He warned against "permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world", saying the United States must concentrate primarily on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term "entangling" alliances. The address quickly set American values regarding foreign affairs.

On July 4, 1798, Washington was commissioned by President John Adams to be lieutenant general and Commander-in-chief of the armies raised or to be raised for service in a prospective war with France. He served as the senior officer of the United States Army between July 13, 1798, and December 14, 1799. He participated in the planning for a Provisional Army to meet any emergency that might arise, but did not take the field. His second in command, Hamilton, led the army.

Throughout the world, men and women were saddened by Washington's death. Napoleon ordered ten days of mourning throughout France; in the United States, thousands wore mourning clothes for months. To protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only three letters between the couple have survived.

, Virginia]]

On December 18, 1799, a funeral was held at Mount Vernon, where his body was interred.

Congress passed a joint resolution to construct a marble monument in the United States Capitol for his body, supported by Martha. In December 1800, the United States House passed an appropriations bill for $200,000 to build the mausoleum, which was to be a pyramid that had a base square. Southern opposition to the plan defeated the measure because they felt it was best to have his body remain at Mount Vernon.

In 1831, for the centennial of his birth, a new tomb was constructed to receive his remains. That year, an attempt was made to steal the body of Washington, but proved to be unsuccessful. Despite this, a joint Congressional committee in early 1832 debated the removal of Washington's body from Mount Vernon to a crypt in the Capitol, built by Charles Bullfinch in the 1820s. Yet again, Southern opposition proved very intense, antagonized by an ever-growing rift between North and South. Congressman Wiley Thompson of Georgia expressed the fear of Southerners when he said: This ended any talk of the movement of his remains, and he was moved to the new tomb that was constructed there on October 7, 1837, presented by John Struthers of Philadelphia. After the ceremony, the inner vault's door was closed and the key was thrown into the Potomac.

1751 profile of Washington is used on this 1908 postage stamp,]] Lee's words set the standard by which Washington's overwhelming reputation was impressed upon the American memory. Washington set many precedents for the national government and the presidency in particular, and was called the "Father of His Country" as early as 1778. Washington's Birthday (celebrated on Presidents' Day), is a federal holiday in the United States.

During the United States Bicentennial year, George Washington was posthumously appointed to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by the congressional joint resolution passed on January 19, 1976, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1976.

Today, Washington's face and image are often used as national symbols of the United States. He appears on contemporary currency, including the one-dollar bill and the quarter coin, and on U.S. postage stamps. Along with appearing on the first postage stamps issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1847,

) in Washington Circle, Washington, D.C.]]

Many things have been named in honor of Washington. Washington's name became that of the nation's capital, Washington, D.C., one of two national capitals across the globe to be named after an American president (the other is Monrovia, Liberia). The state of Washington is the only state to be named after a United States President. George Washington University and Washington University in St. Louis were named for him, as was Washington and Lee University (once Washington Academy), which was renamed due to Washington's large endowment in 1796. Countless American cities and towns feature a Washington Street among their thoroughfares.

The Confederate Seal prominently featured George Washington on horseback, in the same position as a statue of him in Richmond, Virginia.

London hosts a standing statue of Washington, one of 22 bronze identical replicas. Based on Jean Antoine Houdon's original marble statue in the Rotunda of the State Capitol in Richmond, Virginia, the duplicate was given to the British in 1921 by the Commonwealth of Virginia. It stands in front of the National Gallery at Trafalgar Square.

The definitive letterpress edition was begun by the University of Virginia in 1968, and today comprises 52 published volumes, with more to come. It contains everything written by Washington, or signed by him, together with most of his incoming letters. The collection is online.

As a young man, Washington had red hair. A popular myth is that he wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. Washington did not wear a wig; instead, he powdered his hair, as represented in several portraits, including the well known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.

Washington suffered from problems with his teeth throughout his life. He lost his first adult tooth when he was twenty-two and had only one left by the time he became President. John Adams claims he lost them because he used them to crack Brazil nuts but modern historians suggest the mercury oxide, which he was given to treat illnesses such as smallpox and malaria, probably contributed to the loss. He had several sets of false teeth made, four of them by a dentist named John Greenwood. The hippo ivory was used for the plate, into which real human teeth and bits of horses' and donkeys' teeth were inserted. Dental problems left Washington in constant pain, for which he took laudanum. This distress may be apparent in many of the portraits painted while he was still in office, including the one still used on the $1 bill.

On the death of his father in 1743, the 11-year-old inherited 10 slaves. At the time of his marriage to Martha Custis in 1759, he personally owned at least 36 (and the widow's third of her first husband's estate brought at least 85 "dower slaves" to Mount Vernon). Using his wife's great wealth he bought land, tripling the size of the plantation, and additional slaves to farm it. By 1774, he paid taxes on 135 slaves (this does not include the "dowers"). The last record of a slave purchase by him was in 1772, although he later received some slaves in repayment of debts. Washington also used white indentured servants.

One historian claims that Washington desired the material benefits from owning slaves and wanted to give his wife's family a wealthy inheritance. Before the American Revolution, Washington expressed no moral reservations about slavery, but in 1786, Washington wrote to Robert Morris, saying, "There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery." In 1778, he wrote to his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished "to get quit of negroes". Maintaining a large, and increasingly elderly, slave population at Mount Vernon was not economically profitable. Washington could not legally sell the "dower slaves," however, and because these slaves had long intermarried with his own slaves, he could not sell his slaves without breaking up families.

As president, Washington brought seven slaves to New York City in 1789 to work in the first presidential household. Following the transfer of the national capital to Philadelphia in 1790, he brought nine slaves to work in the President's House. At the time of his death, there were 317 slaves at Mount Vernon– 123 owned by Washington, 154 "dower slaves," and 40 rented from a neighbor. Dorothy Twohig argues that Washington did not speak out publicly against slavery, because he did not wish to create a split in the new republic, with an issue that was sensitive and divisive.

Washington was a member of the Anglican Church, which had 'established status' in Virginia (meaning tax money was used to pay its minister). He was a member of and served on the vestry (governing board) for Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia and for Pohick Church near his Mount Vernon home until the war began; however the parish was the unit of local government and the vestry dealt mostly with civic affairs such as roads and poor relief.

According to historian Paul F. Boller Jr., Washington practically speaking was a Deist who had a profound belief and faith in "Divine Providence" or a higher "Divine Will" derived from a "Supreme Being" who controlled human events and as in Calvinism the course of history followed an orderly pattern rather than mere chance. In 1789, Washington claimed that the "Author of the Universe" actively interposed in favor of the American Revolution. However, according to Boller, Washington never made attempts to personalize his own religious views or express any appeal to the aesthetic side of biblical passages. Boller states that Washington's "allusions to religion are almost totally lacking in depths of feeling." In philosophical terms, he admired and adopted the Stoic philosophy of the ancient Romans, which emphasized virtue and humanitarianism and was highly compatible with Deism.

In a letter to George Mason in 1785, Washington wrote that he was not among those alarmed by a bill "making people pay towards the support of that [religion] which they profess," but felt that it was "impolitic" to pass such a measure, and wished it had never been proposed, believing that it would disturb public tranquility.

Washington frequently accompanied his wife to church services; however, there is no record of his ever taking communion, and he would regularly leave services before communion—with the other non-communicants (as was the custom of the day), until, after being admonished by a rector, he ceased attending at all on communion Sundays. As president he made a point of being seen attending services at numerous churches, including Presbyterian, Quaker and Catholic, to show his general support for religion. Washington was known for his generosity. Highly gregarious, he attended many charity events and donated money to colleges, schools and to the poor. As Philadelphia's leading citizen, President Washington took the lead in providing charity to widows and orphans hit by the yellow fever epidemic that devastated the capital city in 1793.

;Sources used For a bibliography see George Washington bibliography

{| class="navbox collapsible collapsed" style="width:100%; margin:auto;" |- ! style="background:#ccf;"| Titles and Succession |- | |}

Category:Articles with inconsistent citation formats Category:1732 births Category:1799 deaths Category:18th-century American Episcopalians Category:18th-century presidents of the United States Category:American farmers Category:American foreign policy writers Category:American people of English descent Category:American planters Category:Chancellors of the College of William & Mary Category:Congressional Gold Medal recipients Category:Continental Army generals Category:Continental Army officers from Virginia Category:Continental Congressmen from Virginia Category:Deaths from pneumonia Category:Deaths from asphyxiation Category:House of Burgesses members Category:Members of the Society of the Cincinnati Category:People from Westmoreland County, Virginia Category:People of Virginia in the American Revolution Category:People of Virginia in the French and Indian War Category:Presidents of the United States Category:Recipients of a posthumous promotion Category:Signers of the United States Constitution Category:United States presidential candidates, 1789 Category:United States presidential candidates, 1792 Category:United States presidential candidates, 1796 Category:Virginia colonial people Category:Washington family Category:British America army officers Category:Washington and Lee University people

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Region | Western philosophy |

|---|---|

| Era | 20th & 21st century |

| Name | George Sotiros Pappas |

| Birth date | 1942 |

| Main interests | epistemology, early Modern Philosophy, esp. Berkeley |

| Notable ideas | Berkeley scholarship |

| Awards | International Berkeley Essay Prize (1993), Emeritus Professor |

He is the author of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Internalist versus Externalist conceptions of epistemic justification.

He was co-editor (with Marshall Swain) of Essays on Knowledge and Justification (1978), regarded as a key anthology of essays relating to the Gettier problem and used as a core text in undergraduate epistemology courses.

George Pappas is an editorial consultant of Berkeley Studies.

Pappas' interpretation of Berkeley's ‘esse is percipi’ thesis has sparked much discussion. In 1989, the Garland Publishing Company brought out a 15-volume collection of major works on Berkeley; Pappas' paper “Abstract ideas and the 'esse is percipi' thesis” was included in the third volume, as it was considered to be a significant contribution to Berkeley scholarship.

Pappas developed his treatment of Berkeley’s “esse est percipi” principle to repudiate the "inherence interpretation of Berkeley", upon which Edwin E. Allaire, among others, elaborated

“That account is put forward to answer an extremely perplexing question in the history of philosophy: Why did Berkeley embrace idealism, i. e., why did he hold that esse est percipi, that to be is to be perceived? (Hausman, Alan. Op. cit. Pp. 421–422.)

After emerging in the early 1960s, the “inherence account” attracted numerous proponents and became an influential element of contemporary Berkeley scholarship. In his paper “Ideas, minds, and Berkeley” Pappas revealed some discrepancies between fountain-head evidences and Allaire’s approach to a reconstruction of Berkeley’s idealism. Pappas' critical examination of the “inherence account” is greatly appreciated by Berkeley scholars. Pappas’ penetrating remarks compelled Edwin B. Allaire to revise and improve his conception. Even those who share Allaire’s account of Berkeley’s idealism acknowledge Pappas’ article to be “an excellent review and critique of the IA [inherence account].”

Category:1942 births Category:American philosophers Category:Epistemologists Category:Living people Category:Ohio State University faculty

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.