I | Confidence and Trust

B. R. Cohen (BC): Questions about trust, faith, and chance in American cultural history are at the core of your work as I see it. Your interest in confidence and con men is especially striking. Fables of Abundance, for example, is ostensibly a cultural history of advertising in America, but it’s more truly a study of how salesmen throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries came to garner trust and faith in a product, how in a marketplace amongst strangers they sought to gain a customer’s confidence in them and their wares.

JACKSON LEARS (JL): I think that’s right. Actually, I’d been thinking that I’d write about confidence games in American history, but I didn’t want it to be just the tabloid version about rogues and scoundrels, even if they’re fascinating and fun. The broader uses of confidence in American culture are more interesting to me, as are what Keynes called “animal spirits.” These are the spontaneous emotions that play a central role in capitalism, despite the persistent myth that “rational self-interest” is at the core of our economic life.

BC: The particular cast to confidence and deception, your history of advertising shows, is one tied up in economic markets and financial transactions. It deals with those charlatans and hucksters of the Gilded Age, the cagey, conniving street peddlers of what we’d rather think was a premodern world. How much cultural basis for the confidence game is universal and timeless? How much is it American?

JL: If not universal, it’s at least widely shared by various threads of tradition and historical circumstances. Here are two examples. When I was writing Fables of Abundance I found certain examples of the mountebank from Italy, among other places, in the late Middle Ages. The original mountebank is a guy who, plainly enough, mounts a bench in the town square to sell his magic, a little prayer written on pieces of paper and wrapped up in a small cylindrical container, sold to people to cure their ills. This is not formally orthodox or recognized by the Church, but it created this religious aura around the mountebank. There’s also Melville’s great Confidence-Man, his portrayal of a host of characters of ill repute and questionable virtue, all trying to represent themselves as something they aren’t. Melville’s setting is a Mississippi River steamboat, but this doesn’t mean the problem is strictly American.

BC: Maybe in the American setting the distance from an official church helps explain why the confidence and deception that get bound up with faith and hope have more to do with capitalistic structures or sales or market-based mechanisms, a context that is much more dominant here.

JL: Absolutely, the confidence games take the form of their setting. In capitalist settings, it’s multivalent. Not only does one need confidence to trust the merchant who’s selling you an item, but the merchant needs confidence to start his own business, he needs it to invest, and the market needs it to be propelled forward. Of course we’re sitting here talking about this in the shadow of the banking crisis and recession! The cultural feature we’re talking about may be common to human interaction, no matter the specific setting, but those specific settings—a Mississippi River steamboat in the the mid-nineteenth century, or Catholic Italy a half millennium before—give form to its expression.

II | “All history is the history of unintended consequences”

BC: Those cultural features bring to mind a comment someone made calling you the Dean of Cultural Historians. How you define that field?

JL: I understand cultural history as the history of meanings, of how people make meanings—often in a helter-skelter way. It isn’t just conscious construction. It comes about through people expressing their anxieties, aspirations, and fears, their longings, prejudices, tacit assumptions. My job is to unpack the ways the personal is always political and vice versa—of how, for example, apparently arcane policy documents are rooted in visceral desires, whether it’s Teddy Roosevelt expressing his own ideals of character and virtue writ large with antitrust policies and imperial crusades, or George W. Bush, a century later, launching a global “war on terror” that satisfies (among other things) his own emotional needs.

BC: What is that historical study for? How do you see the public importance of historical inquiry today?

JL: My view is that just as anthropologists and geographers help us overcome our cultural and spatial provincialism, so historians have a job to do with temporal provincialism. The humanities, generally, get people outside their own skin, and give them access to the mentality of a remote place or time or culture, another worldview. We’re in a situation in the 21st century where most journalists and other shapers of conventional wisdom have known nothing but Reaganism and its descendants; they’ve never experienced a war that was actually declared by the US congress, a world of progressive taxation, or for that matter one where welfare benefits were defended as welfare. Neoliberalism has outlasted that memory, making historical work that much more important.

BC: And your work calls out those historical moments that got us here?

JL: One of the aphorisms I resort to in Rebirth of a Nation is, “All history is the history of longing,” but I also felt another aphorism was on point, which is that “History is essentially tragic.” What I mean is not that history is sad, though it often is, but that, to paraphrase the historian E. P. Thompson, all history is the history of unintended consequences. If you look at the growth of cultural history from the later 1970s, when I came into the field, you find an effort to get beyond both a social history that had become largely quantitative and an intellectual history that had become somewhat distanced from everyday life. One thing that helped this effort, especially into the 1980s, was the growth of semiotics. Here was a theory that said meaning doesn’t descend from on high, from some abstract realm of ideas, but rather that meaning adheres in artifacts, whether those artifacts are a sermon or a roller coaster or a radio. That creation of meaning isn’t always intentional; it’s made by people as they live.

BC: It’s a philosophy of history that suggests activity and process, then. It’s a history of peoples’ choices and decisions-in-the-making, not the static summary of the worlds they lived in after the fact.

JL: Well, by the later 1970s, social historians were beginning to say, you know this is really kind of boring, just counting people. If you want to write a family history, say, you need to know more about working-class culture and consciousness, not just the size of a family. If you want to do labor history it has to be more than just an accounting of public policy; you’ve got to try to get into how working people made meaning. So, cultural history becomes a kind of common ground, a hybrid space for what I’m calling the history of meaning. Cultural historians try to burrow beneath the surface of utterances and claims and arguments, to tell us more about how divided we are as selves and how we all want conflicting things, to show how even the best-intentioned efforts can lead to confused and sometimes self-defeating outcomes. That’s the tragedy. Cultural history can be chastening, giving us an awareness of the possibility that we are over-reaching, even while it could also tell us how to do things better—to change capitalism, for example, or to care for one another as people, as families and neighbors and nations.

BC: What about your own work? How did you get onto the theme, broadly, of the historical shift from the religious to the secular?

JL: It wasn’t direct, I know that, but it certainly had to do with the issues of how people make meaning of their worlds. My original attraction to the Gilded Age, the period in the shadow of the Civil War, grew out of fascination with the religious crisis of the era. So many people were wrestling, as were William James, Henry Adams, and their generation, with the question of how to be an intelligent, skeptical person and yet at the same time somehow sustain what was nourishing about traditional belief. They had to walk that tightrope between faith and doubt. Although I’ve ultimately become more skeptical and more secular as time goes on in my own life, I still find myself attracted to those divided selves, because my own self is divided. I think of this wonderful scene in Conrad’s short story “The Secret Agent,” where the professor character—he’s one of the anarchists trying to blow up the Greenwich Observatory and knock the bourgeoisie on its back—this character is speculating with his comrades about what human beings really want. Then he leans back in his chair, and you can’t see him because of the light, but he announces, “Mankind does not know what it wants.” That confusion about wants is what I’m trying to reconstruct, to illuminate, by writing cultural history.

III | Credit and Thrift

BC: You mentioned the triumph of a kind of free-market ideology as having wiped away historical memory. Isn’t that disheartening for a scholar, that the world you’ve uncovered is shut out?

JL: I might think of it another way. Contemporary amnesia is a compelling reason for renewed commitment to uncover the lost or ambiguous meanings of words and ideas we take for granted. Take confidence again, or trust. Or think of credit and debt, about giving and earning credit, or about owing a debt of gratitude to someone. Although these are economic terms, their meanings are more complex and have shifted historically.

BC. I was thinking of “credit” and how accreditation shows up everywhere now.

JL: Certainly within academia! This is a business school mentality, that education can be measured with precision on sheets of papers with lists and checkmarks. Accreditation—it’s about who gives you credit, and how you can persuade them to do so. It’s trust and confidence again. Who do we trust? Who do we have faith in to say that we’ve done the right thing?

BC: It’s a case where moral measures get redefined as economic ones.

JL: It’s a question of market models intervening in what we like to think of as the sacrosanct realm of the university. Once upon a time it was thought that we had special things to offer, certain traditions of knowledge that we had built up over years and that we, as professionals, had tapped into sufficiently to gain our legitimacy. Isn’t that the vision that brought you into academic life too?

BC: You got it. I worked in industry for a few years and thought the academy would help me escape the downsides of the corporation.

JL: In my case, I was an undergraduate walking past a quote of Jefferson’s on my way to class every day: “For here we are not afraid to follow the truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” So we aren’t afraid. We can teach these things about history, about culture, error, reason, maybe even ideas about truth, and train other people to teach things. But with the business model—and this is a consumer model of education—you have to justify the trust not as someone who possesses knowledge, the tradition, but on the basis of how you’re satisfying your consumers within a market of purchasers. This comes along with an erosion of faculty autonomy. That’s another example of the erosion of trust, in professors whose credit comes from years of knowledgeable reflection and debate. Instead, confidence is placed in checklist metrics, a disembodied form, which has to be renewed each year.

BC: On the one hand, we’re asking for a return to some ethos that the market has taken over, but on the other hand, if you do the historical studies of confidence and trust, it seems pretty timeless. Has it ever been otherwise? Or were these meanings always corrupted? Perhaps by the church rather than the market?

JL: That’s how I would look at it, judging by our example of the mountebank in the town square. And, of course, from the Protestant point of view, we can think of the sale of indulgences, the ultimate scourge that drove Luther out of the Church.

BC: That also brings the moral and the economic to the fore.

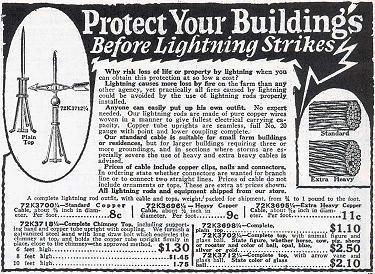

JL: We brought up Melville before. There’s a wonderful scene in his short story “The Lightning-Rod Man,” which was kind of a dress rehearsal for The Confidence-Man. The protagonist is a lightning-rod salesman. He may be the ultimate confidence man in the 19th century, in that he promises to take this extraordinary force of nature and channel it safely into the ground. This is really titanic power, the power that is a direct expression of a kind of theology. In the story, a homeowner challenges the lightning-rod man, challenges his credit, his character, and at one point she says, Get out, leave my house and shut the door, you Tetzel! In Luther’s Europe, Tetzel was the big indulgence salesman. By alluding to Tetzel, the guy that focuses Luther’s ire, Melville makes a direct connection between priests and lightning-rod salesmen—they’re both selling protection from divine wrath. The lighting-rod man is a Tetzel for a Protestant America and for a scientific America too, because the lightning rod is a scientific product, an expression of efforts to understand the invisible, awesome power of electricity, linked to Ben Franklin himself.

IV | “Be brave, but never take chances”

BC: We started off talking about ideas of fate, chance, and control, and those keep circling through our conversation.

JL: If you connect those themes back to the salesman, there’s another element at stake: the idea of selling comfort, a condition where your risk is reduced. Like an insurance salesmen, striking with fear but offering to quell the risks of everyday life. “Risk” doesn’t have the same moral cache as, say, redemption or salvation, but it crosses from a cultural to an economic world. The value of risk, or the danger of it, is so complicated, in probably the same sense as confidence. A businessperson needs to have confidence to invest, to believe in a product, and so, too, for risk. Taking risks is important; it’s a valuable function of the economy. Risk is rewarded and cherished and applauded.

BC: So long as it’s someone else bearing the responsibility.

JL: That’s right. If things don’t work out, well, the one who took the risk is often protected while others are subject to the consequences of the risk. I have always thought of the Reagan era as one where risk gets resurrected, where the ways Progressives tried to lay out terms for social welfare, taking care of one another during the early decades of the century, were finally pushed aside for risk takers who would benefit from the chances while the rest of us took the responsibility to clean it up if they failed. Which they often do.

BC: Sounds like you’re talking about the banking crisis again.

JL: Or the Savings and Loan crisis before that. Or the unregulated speculation of the late 1920s.

BC: You’ve quoted Roy Rogers elsewhere: “Be brave, but never take chances.”

JL: Right, that 1950s kids’ version—that was the sign-off to his TV show. Be brave, but only bet on a sure thing.

BC: There’s a sense that you can have it all.

JL: It was probably meant to reassure parents. But it comes from a world, 1950s America, where risk has an ambiguous status. The post–World War II era in this country was, in many ways, the fulfillment of a yearning back in the Progressive Era for safety and security, and protection from the well-diagnosed abrasions of the marketplace. I tell my students a story about a very broad movement in the cultural history of 20th-century America organized around the formation, consolidation, and then fragmentation of the managerial consensus. The Progressives began the vision, an idea that you can organize and manage society in a way to be humane and helpful to all, in a way that will soften the corrosive effect of capitalism. Whether they called it a “cooperative commonwealth” or something else, it was idealized as a coming together of people around a vision of society based on the common welfare of its citizens.

BC: You’re talking about the pre–World War I years mostly? The Pure Food Act, public education, national parks, conservation?

JL: When that vision was formed, yes; but it isn’t until the late 1930s, when a bargain is struck between capital and labor, that the vision is realized. The big unions finally get recognized and management says, OK, you get an eight-hour day, steady work, steadily rising wages—just don’t question any of our shop floor practices. We’ll Taylorize your work and jerk you around for eight hours on the job, but the rest of the time we’ll pay you enough money. You can buy a house, you can buy a boat, take it to the lake, buy a refrigerator, buy a washing machine. This bargain comes into being, and by the 1950s, you have, in effect, a fulfillment of the longings of the 1930s, longings for acceptance into a transcendent community. It’s what Henry Fonda talks about in the film version of that scene in The Grapes of Wrath, when Tom Joad says, Maybe we’re all just part of one big soul … It’s a mythical collectivism. We have strong unions, we have high employment, relatively secure jobs—obviously not everyone, there were a good many people excluded from the so-called consensus by reasons of race or class or gender—but there is this moment, and in some ways an accidental moment, that we were the only rich country in the world. Europe is rubble. US corporations are insulated from the world markets. It’s only in the late 1960s, early 1970s, when downsizing starts, a cutback in labor costs enabled by finding cheaper ways to make things overseas, and along with this you find the return of a deregulatory, laissez-faire creed.

BC: Which gives rise to our current neoliberal moment.

JL: We’ve been talking around that this whole time, haven’t we? I know I said it’s wiped out historical memory, but it certainly hasn’t satisfied nostalgic yearnings. You see this with right-wing pronouncements that the US must return to the good old days, even if that means little more than resurrecting Reagan’s “Morning in America.” What worries me is not just that we have to re-teach and re-learn all the lessons about the dangers—the risks—of laissez-faire from a century ago, but that as we were saying before, while we moved from the religious to the secular, now we find a more recent reduction from the cultural to the economic. Credit, redemption, voucher, thrift—all these meaningful human concepts have been impoverished. The reduction of the moral to the financial is so complete that risk is only seen as a number on an investment banker’s computer screen. Neoliberalism seems to me precisely the ideology that celebrates risks for the multitude while protecting the handful.

BC: The culmination of treating corporations as people with all the rights but none of the responsibilities. They get to be brave, you don’t get to take chances.

JL: Roy Rogers speaks to us still.

Please login to comment