About this Author

Derek Lowe, an Arkansan by birth, got his BA from Hendrix College and his PhD in organic chemistry from Duke before spending time in Germany on a Humboldt Fellowship on his post-doc. He's worked for several major pharmaceutical companies since 1989 on drug discovery projects against schizophrenia, Alzheimer's, diabetes, osteoporosis and other diseases.

To contact Derek email him directly: derekb.lowe@gmail.com

Twitter: Dereklowe

|

In the Pipeline: Don't miss Derek Lowe's excellent commentary on drug discovery and the pharma industry in general at In the Pipeline

June 5, 2013

Posted by Derek

Chiral catalyst reactions seem to show up on both lists when you talk about new reactions: the list of "Man, we sure do need more of those" and the "If I see one more paper on that I'm going to do something reckless" list.

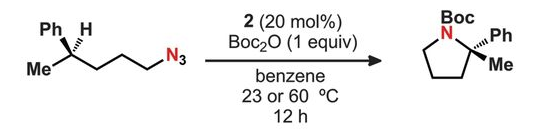

I sympathize with the latter viewpoint, but the former is closer to reality. What we don't need are more lousy chiral catalyst papers, though, on that I think we can all agree. So I wanted to mention a good one, from Erick Carreira's group at the ETH. They're trying something that we're probably going to be seeing more of in the future: a "dual-catalyst" approach:

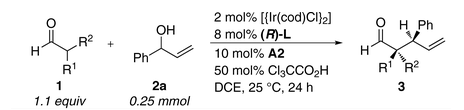

In a conceptually different construct aimed at the synthesis of compounds with a pair of stereogenic centers, two chiral catalysts employed concurrently could dictate the configuration of the stereocenters in the product. Ideally, these would operate independently and set both configurations in a single transition state with minimal matched/mismatched interactions. Herein, we report the realization of this concept in the development of a method for the stereodivergent dual-catalytic α-allylation of aldehydes.

Shown is a typical reaction scheme. They're doing iridium-catalysed allylation reactions, which are already known via the work of Hartwig and others, but with a chiral catalyst to activate the nucleophilic end of the reaction and a separate one for the electrophilic end. That lets you more or less dial in the stereocenters you want in the product. It looks like the allyl alcohol need some sort of aryl group, although they can get it to work with a variety of those. The aldehyde component can vary more widely.

You'd expect a scheme like this to have some combinations that work great, but other mismatched ones that struggle a bit. But in this case the yields stay at 60 to 80%, and the ee values are >99% across the board as they switch things around, which is why we're reading this in Science rather than in, well, you can fill in the names of some other journals as well as I can. Making a quaternary chiral center next to a tertiary one in whatever configuration you want is not something you see every day.

I think that chiral multi-catalytic systems will be taking up even more journal pages than ever in the future. It really seems like a way to get things to perform, and there's certainly enough in the idea to keep a lot of people occupied for a long time. Those of us doing drug discovery should resist the urge to flip the pages too quickly, too, because if we really mean all that stuff about making more three-dimensional molecules, we're going to have to do better with chirality than "Run it down an SFC and throw half of it away".

Comments (0)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

Posted by Derek

If you're in iPad sort of chemist (one of Baran's customers?), you may well already know that app versions of ChemDraw and Chem3D came out yesterday for that platform. I haven't tried them out myself, not (yet) being a swipe-and-poke sort of guy, but at $10 for the ChemDraw app (and Chem3D for free), it could be a good way to get chemical structures going on your own tablet.

Andre the Chemist has a writeup on his experiences here. As an inorganic chemist, he's run into difficulties with text labels, but for good ol' organic structures, things should be working fine. I'd be interested in hearing hands-on reviews of the software in the comments: how does the touch-screen interface work out for drawing? Seems like it could be a good fit. . .

Update: here's a review at MacInChem, and one at Chemistry and Computers.

Comments (7)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

June 4, 2013

Posted by Derek

Late last year came word that the AstraZeneca/Rigel compound, fostamatinib, had failed to show any benefit versus AbbVie's Humira in the clinic. Now they've gritted their corporate teeth and declared failure, sending the whole program back to Rigel.

I've lost count of how many late-stage clinical wipeouts this makes for AZ, but it sure is a lot of them. The problem is, it's hard to say just how much of this is drug discovery itself (after all, we have brutal failure rates even when things are going well), how much of it is just random bad luck, or what might be due to something more fundamental about target and compound selection. At any rate, their CEO, Pascal Soriot, has a stark backdrop against which to perform. Odds are, things will pick up, just by random chance if by nothing else. But odds are, that may not be enough. . .

Comments (15)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Clinical Trials

Posted by Derek

I see that Neil Withers is trying to start up a new discussion in that "Kudzu of Chemistry" comment thread. The main topic is what reactions and chemistry we see too much of, but he's wondering what we should see more of. It's a worthwhile question, but I wonder if it'll be hard to answer. Personally, I'd like to see more reactions that let me attach primary and secondary amines directly into unactivated alkyl CH bonds, but I'm not going to arrange my schedule around that waiting period.

So maybe we should stick with reactions (or reaction types) that have been reported, but don't seem to be used as much as they should. What are the unsung chemistries that should be more famous? What reactions have you seen that you can't figure out why no one's ever followed up on them? I'll try to add some of my own in the comments as the day goes on.

Comments (21)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

June 3, 2013

Posted by Derek

Here's a worthwhile paper from Donna Huryn, Lynn Resnick, and Peter Wipf on the academic contributions to chemical biology in recent years. They're not only listing what's been done, they're looking at the pluses and minuses of going after probe/tool compounds in this setting:

The academic setting provides a unique environment distinct from traditional pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies, which may foster success and long-term value of certain types of probe discovery projects while proving unsuitable for others. The ability to launch exploratory high risk and high novelty projects from both chemistry and biology perspectives, for example, testing the potential of unconventional chemotypes such as organometallic complexes, is one such distinction. Other advantages include the ability to work without overly constrained deadlines and to pursue projects that are not expected to reap commercial rewards, criteria and constraints that are common in “big pharma.” Furthermore, projects to identify tool molecules in an academic setting often benefit from access to unique and highly specialized biological assays and/or synthetic chemistry expertise that emerge from innovative basic science discoveries. Indeed, recent data show that the portfolios of academic drug discovery centers contain a larger percentage of long-term, high-risk projects compared to the pharmaceutical industry. In addition, many centers focus more strongly on orphan diseases and disorders of third world countries than commercial research organizations. In contrast, programs that might be less successful in an academic setting are those that require significant resources (personnel, equipment, and funding) that may be difficult to sustain in a university setting. Projects whose goals are not consistent with the educational mission of the university and cannot provide appropriate training and/or content for publications or theses would also be better suited for a commercial enterprise.

Well put. You have to choose carefully (just as commercial enterprises have to), but there are real opportunities to do something that's useful, interesting, and probably wouldn't be done anywhere else. The examples in this paper are sensors of reactive oxygen species, a GPR30 ligand, HSP70 ligands, an unusual CB2 agonist (among other things), and a probe of beta-amyloid.

I agree completely with the authors' conclusion - there's plenty of work for everyone:

By continuing to take advantage of the special expertise resident in university settings and the ability to pursue novel projects that may have limited commercial value, probes from academic researchers can continue to provide valuable tools for biomedical researchers. Furthermore, the current environment in the commercial drug discovery arena may lead to even greater reliance on academia for identifying suitable probe and lead structures and other tools to interrogate biological phenomena. We believe that the collaboration of chemists who apply sound chemical concepts and innovative structural design, biologists who are fully committed to mechanism of action studies, institutions that understand portfolio building and risk sharing in IP licensing, and funding mechanisms dedicated to provide resources leading to the launch of phase 1 studies will provide many future successful case studies toward novel therapeutic breakthroughs.

But it's worth remembered that bad chemical biology is as bad as anything in the business. You have the chance to be useless in two fields at once, and bore people across a whole swath of science. Getting a good probe compound is not like sitting around waiting for the dessert cart to come - there's a lot of chemistry to be done, and some biology that's going to be tricky almost by definition. The examples in this paper should spur people on to do the good stuff.

Comments (4)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical Biology

Posted by Derek

Chemistry, like any other human-run endeavor, goes through cycles and fads. At one point in the late 1970s, it seemed as if half the synthetic organic chemists in the world had made cis-jasmone. Later on, a good chunk of them switched to triquinane synthesis. More recently, ionic liquids were all over the literature for a while, and while it's not like they've disappeared, they're past their publishing peak (which might be a good thing for the field).

So what's the kudzu of chemistry these days? One of my colleagues swears that you can apparently get anything published these days that has to do with a BODIPY ligand, and looking at my RSS journal feeds, I don't think I have enough data to refute him. There are still an awful lot of nanostructure papers, but I think that it's a bit harder, compared to a few years ago, to just publish whatever you trip over in that field. The rows of glowing fluorescent vials might just have eased off a tiny bit (unless, of course, that's a BODIPY compound doing the fluorescing!) Any other nominations? What are we seeing way too much of?

Comments (31)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News | The Scientific Literature

May 31, 2013

Posted by Derek

For those who are into total synthesis of natural products, Arash Soheili has a Twitter account (Total_Synthesis) that keeps track of all the reports in the major journals. He's emailed me with a link to a searchable database of all these, which brings a lot of not-so-easily-collated information together into one place. Have a look! (Mostly, when I see these, I'm very glad that I'm not still doing them, but that's just me).

Comments (1)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

Posted by Derek

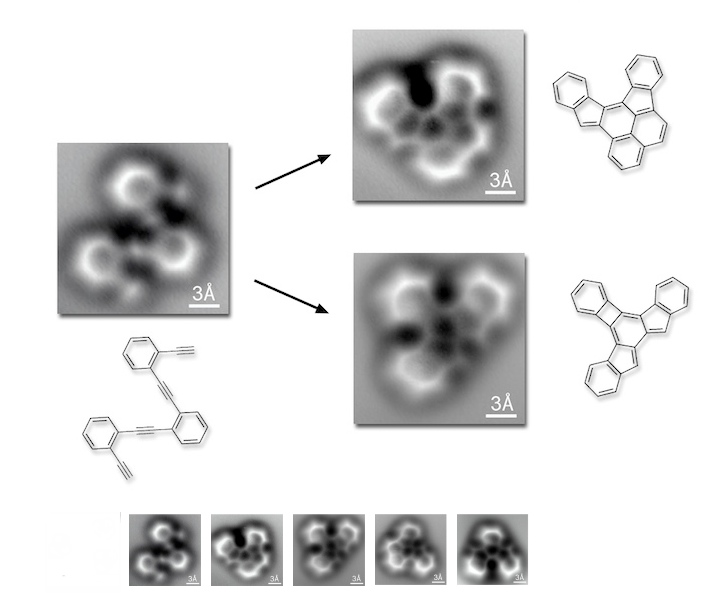

It's molecular imaging week! See Arr Oh and others have sent along this paper from Science, a really wonderful example of atomic-level work. (For those without journal access, Wired and PhysOrg have good summaries).

As that image shows, what this team has done is take a starting (poly) phenylacetylene compound and let it cyclize to a variety of products. And they can distinguish the resulting frameworks by direct imaging with an atomic force microscope (using a carbon monoxide molecule as the tip, as in this work), in what is surely the most dramatic example yet of this technique's application to small-molecule structure determination. (The first use I know of, from 2010, is here). The two main products are shown, but they pick up several others, including exotica like stable diradicals (compound 10 in the paper).

There are some important things to keep in mind here. For one, the only way to get a decent structure by this technique is if your molecules can lie flat. These are all sitting on the face of a silver crystal, but if a structure starts poking up, the contrast in the AFM data can be very hard to interpret. The authors of this study had this happen with their compound 9, which curls up from the surface and whose structure is unclear. Another thing to note is that the product distribution is surely altered by the AFM conditions: a molecule in solution will probably find different things to do with itself than one stuck face-on to a metal surface.

But these considerations aside, I find this to be a remarkable piece of work. I hope that some enterprising nanotechnologists will eventually make some sort of array version of the AFM, with multiple tips splayed out from each other, with each CO molecule feeding to a different channel. Such an AFM "hand" might be able to deconvolute more three-dimensional structures (and perhaps sense chirality directly?) Easy for me to propose - I don't have to get it to work!

Comments (21)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Analytical Chemistry | Chemical News

May 30, 2013

Posted by Derek

Here's a question for the organic chemists in the crowd, and not just those in the drug industry, either. Over the last few years, though, there's been a lot of discussion about how drug company compound libraries have too many compounds with too many aromatic rings in them. Here are some examples of just the sort of thing I have in mind. As mentioned here recently, when you look at real day-to-day reactions from the drug labs, you sure do see an awful lot of metal-catalyzed couplings of aryl rings (and the rest of the time seems to be occupied with making amides to link more of them together).

Now, it's worth remembering that some of the studies on this sort of thing have been criticized for stacking the deck. But at the same time, it's undeniable that the proportion of "flat stuff" has been increasing over the years, to the point that several companies seem to be openly worried about the state of their screening collections.

So here's the question: if you're trying to break out of this, and go to more three-dimensional structures with more saturated rings, what are the best ways to do that? The Diels-Alder reaction has come up here as an example of the kind of transformation that doesn't get run so often in drug research, and it has to be noted that it provides you with instant 3-D character in the products. What we could really use are reactions that somehow annulate pyrrolidines or tetrahydropyrans onto other systems in one swoop, or reliably graft on spiro systems where there was a carbonyl, say.

I know that there are some reactions like these out there, but it would be worthwhile, I think, to hear what people think of when they think of making saturated heterocyclic ring systems. Forget the indoles, the quinolines, the pyrazines and the biphenyls: how do you break into the tetrahydropyrans, the homopiperazines, and the saturated 5,5 systems? Embrace the stereochemistry! (This impinges on the topic of natural-product-like scaffolds, too).

My own nomination, for what it's worth, is to use D-glucal as a starting material. If you hydrogenate that double bond, you now have a chiral tetrahydropyran triol, with differential reactivity, ready to be functionalized. Alternatively, you can go after that double bond to make new fused rings, without falling back into making sugars. My carbohydrate-based synthesis PhD work is showing here, but I'm not talking about embarking on a 27-step route to a natural product here (one of those per lifetime is enough, thanks). But I think the potential for library synthesis in this area is underappreciated.

Comments (28)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News | Life in the Drug Labs

Posted by Derek

Here's a follow-up on the news that bexarotene might be useful for Alzheimer's. Unfortunately, what seems to be happening is what happens almost every time that the word "Alzheimer's" is mentioned along with a small molecule. As Nature reports here, further studies are delivering puzzling results.

The original work, from the Landreth lab at Case Western, reported lower concentrations of soluble amyloid, memory improvements in impaired rodents, and (quite strikingly), clearance of large amounts of existing amyloid plaque in their brain tissue. Now four separate studies (1, 2, 3, 4) are out in the May 24th issue of Science, and the waters are well muddied. No one has seen the plaque clearance, for one thing. Two groups have noted a lowering of soluble amyloid, though, and one study does report some effects on memory in a mouse model.

So where are we? Here's Landreth himself on the results:

It was our expectation other people would be able to repeat this,” says Landreth about the results of the studies. “Turns out that wasn’t the case, and we fundamentally don’t understand that.” He suggests that the other groups might have used different drug preparations that altered the concentration of bexarotene in the brain or even changed its biological activity.

In a response published alongside the comment articles, Landreth emphasizes that some of the studies affirm two key conclusions of the original paper: the lowering of soluble β-amyloid levels and the reversal of cognitive deficits. He says that the interest in plaques may even be irrelevant to Alzheimer’s disease.

That last line of thought is a bit dangerous. It was, after all, the plaque clearance that got this work all the attention in the first place, so to claim that it might not be that big a deal once it failed to repeat looks like an exercise in goalpost-shifting. There might be something here, don't get me wrong. But chasing it down is going to be a long-term effort. It helps, of course, that bexarotene has already been out in clinical practice for a good while, so we already know a lot about it (and the barriers to its use are lower). But there's no guarantee that it's the optimum compound for whatever this effect is. We're in for a long haul. With Alzheimer's, we're always in for a long haul, it seems. I wish it weren't so.

Comments (7)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Alzheimer's Disease

May 29, 2013

Posted by Derek

You'd think that by now we'd know all there is to know about the side effects of sulfa drugs, wouldn't you? These were the top-flight antibiotics about 80 years ago, remember, and they've been in use (in one form or another) ever since. But some people have had pronounced CNS side effects from their use, and it's never been clear why.

Until now, that is. Here's a new paper in Science that shows that this class of drugs inhibits the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for a number of hydroxylase and reductase enzymes. And that in turn interferes with neurotransmitter levels, specifically dopamine and serotonin. The specific culprit here seems to be sepiapterin reductase (SPR). Here's a summary at C&E; News.

This just goes to show you how much there is to know, even about things that have been around forever (by drug industry standards). And every time something like this comes up, I wonder what else there is that we haven't uncovered yet. . .

Comments (16)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Infectious Diseases | Toxicology

Posted by Derek

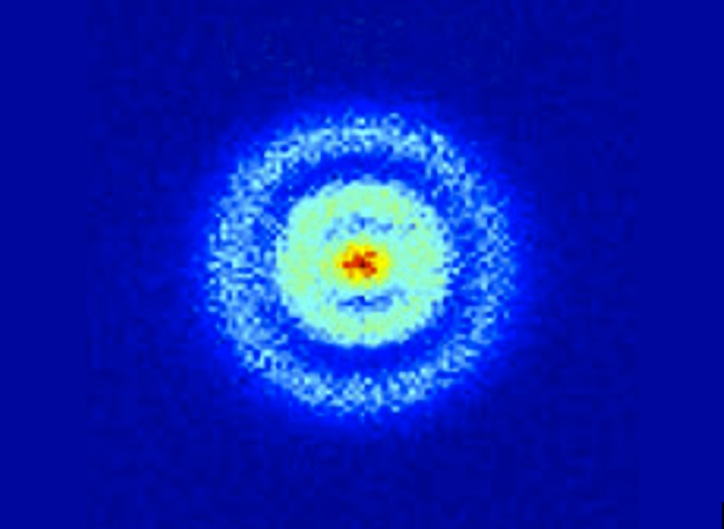

Here's another one of those images that gives you a bit of a chill down the spine. You're looking at a hydrogen atom, and those spherical bands are the orbitals in which you can find its electron. Here, people, is the wave function. Yikes.Update: true, what you're seeing are the probability distributions as defined by the wave function. But still. . .

This is from a new paper in Physical Review Letters (here's a commentary at the APS site on it). Technically, what we're seeing here are Stark states, which you get when the atom is exposed to an electric field. Here's more on how the experiment was done:

In their elegant experiment, Stodolna et al. observe the orbital density of the hydrogen atom by measuring a single interference pattern on a 2D detector. This avoids the complex reconstructions of indirect methods. The team starts with a beam of hydrogen atoms that they expose to a transverse laser pulse, which moves the population of atoms from the ground state to the 2s and 2p orbitals via two-photon excitation. A second tunable pulse moves the electron into a highly excited Rydberg state, in which the orbital is typically far from the central nucleus. By tuning the wavelength of the exciting pulse, the authors control the exact quantum numbers of the state they populate, thereby manipulating the number of nodes in the wave function. The laser pulses are tuned to excite those states with principal quantum number n equal to 30.

The presence of the dc field places the Rydberg electron above the classical ionization threshold but below the field-free ionization energy. The electron cannot exit against the dc field, but it is a free particle in many other directions. The outgoing electron wave accumulates a different phase, depending on the direction of its initial velocity. The portion of the electron wave initially directed toward the 2D detector (direct trajectories) interferes with the portion initially directed away from the detector (indirect trajectories). This produces an interference pattern on the detector. Stodolna et al. show convincing evidence that the number of nodes in the detected interference pattern exactly reproduces the nodal structure of the orbital populated by their excitation pulse. Thus the photoionization microscope provides the ability to directly visualize quantum orbital features using a macroscopic imaging device.

n=30 is a pretty excited atom, way off the ground state, so it's not like we're seeing a garden-variety hydrogen atom here. But the wave function for a hydrogen atom can be calculated for whatever state you want, and this is what it should look like. The closest thing I know of to this is the work with field emission electron microscopes, which measure the ease of moving electrons from a sample, and whose resolution has been taken down to alarming levels).

So here we are - one thing after another that we've had to assume is really there, because the theory works out so well, turns out to be observable by direct physical means. And they are really there. Schoolchildren will eventually grow up with this sort of thing, but the rest of us are free to be weirded out. I am!

Comments (15)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: General Scientific News

May 28, 2013

Posted by Derek

Readers may recall the bracing worldview of Valeant CEO Mike Pearson. Here's another dose of it, courtesy of the Globe and Mail. Pearson, when he was brought in from McKinsey, knew just what he wanted to do:

Pearson’s next suggestion was even more daring: Cut research and development spending, the heart of most drug firms, to the bone. “We had a premise that most R&D; didn’t give good return to shareholders,” says Pearson. Instead, the company should favour M&A; over R&D;, buying established treatments that made enough money to matter, but not enough to attract the interest of Big Pharma or generic drug makers. A drug that sold between $10 million and $200 million a year was ideal, and there were a lot of companies working in that range that Valeant could buy, slashing costs with every purchase. As for those promising drugs it had in development, Pearson said, Valeant should strike partnerships with major drug companies that would take them to market, paying Valeant royalties and fees.

It's not a bad strategy for a company that size, and it sure has worked out well for Valeant. But what if everyone tried to do the same thing? Who would actually discover those drugs for inlicensing? That's what David Shayvitz is wondering at Forbes. He contrasts the Valeant approach with what Art Levinson cultivated at Genentech:

While the industry has moved in this direction, it’s generally been slower and less dramatic than some had expected. In part, many companies may harbor unrealistic faith in their internal R&D; programs. At the same time, I’ve heard some consultants cynically suggest that to the extent Big Pharma has any good will left, it’s due to its positioning as a science-driven enterprise. If research was slashed as dramatically as at Valeant, the industry’s optics would look even worse. (There’s also the non-trivial concern that if Valeant’s acquisition strategy were widely adopted, who would build the companies everyone intends to acquire?)

The contrasts between Levinson’s research nirvana and Pearson’s consultant nirvana (and scientific dystopia) could hardly be more striking, and frame two very different routes the industry could take. . .

I can't imagine the industry going all one way or all the other. There will always be people who hope that their great new ideas will make them (and their investors) rich. And as I mentioned in that link in the first paragraph, there's been talk for years about bigger companies going "virtual", and just handling the sales and regulatory parts, while licensing in all the rest. I've never been able to quite see that, either, because if one or more big outfits tried it, the cost of such deals would go straight up - wouldn't they? And as they did, the number would stop adding up. If everyone knows that you have to make deals or die, well, the price of deals has to increase.

But the case of Valeant is an interesting and disturbing one. Just think over that phrase, ". . .most R&D; didn't give good return to the shareholders". You know, it probably hasn't. Some years ago, the Wall Street Journal estimated that the entire biotech industry, taken top to bottom across its history, had yet to show an actual profit. The Genentechs and Amgens were cancelled out, and more, by all the money that had flowed in never to be seen again. I would not be surprised if that were still the case.

So, to steal a line from Oscar Wilde (who was no stranger to that technique), is an R&D-driven; startup the triumph of hope over experience? Small startups are the very definition of trying to live off returns of R&D;, and most startups fail. The problem is, of course, that any Valeants out there need someone to do the risky research for there to be something for them to buy. An industry full of Mike Pearsons would be a room full of people all staring at each other in mounting perplexity and dismay.

Comments (32)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Drug Industry History

May 24, 2013

Posted by Derek

There's a new paper out today in Nature on a very unusual way to determine the chirality of organic molecules. It uses an exotic effect of microwave spectroscopy, and I will immediately confess that the physics is (as of this morning, anyway) outside my range.

This is going to be one of those posts that comes across as gibberish to the non-chemists in the audience. Chirality seems to be a concept that confuses people pretty rapidly, even though the examples of right and left shoes or gloves (or right and left-handed screw threads) are familiar from everyday objects, and exactly the same principles apply to molecules. But the further you dig into the concept, the trickier it gets, and when you start dragging the physics of it in, you start shedding your audience quickly. Get a dozen chemists together and ask them how, exactly, chiral compounds rotate plane-polarized light and see how that goes. (I wouldn't distinguish myself by the clarity of my explanation, either).

But this paper is something else again. Here, see how you do:

Here we extend this class of approaches by carrying out nonlinear resonant phase-sensitive microwave spectroscopy of gas phase samples in the presence of an adiabatically switched non-resonant orthogonal electric field; we use this technique to map the enantiomer-dependent sign of an electric dipole Rabi frequency onto the phase of emitted microwave radiation.

The best I can do with this is that the two enantiomers have the same dipole moment, but that the electric field interacts with them in a manner that gives different signs. This shows up in the phase of the emitted microwaves, and (as long as the sample is cooled down, to cut back on the possible rotational states), it seems to give a very clear signal. This is a completely different way to determine chirality from the existing polarized-light ones, or the use of anomalous dispersion in X-ray data (although that one can be tricky).

Here's a rundown on this new paper from Chemistry World. My guess is that this is going to be one of those techniques that will be used rarely, but when it comes up it'll be because nothing else will work at all. I also wonder if, possibly, the effect might be noticed on molecules in interstellar space under the right conditions, giving us a read on chirality from a distance?

Comments (12)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

May 23, 2013

Posted by Derek

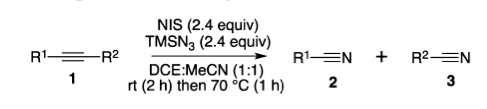

Put this one in the category of "reactions you probably wouldn't have thought of". There's a new paper in Organic Letters on cleaving a carbon-carbon triple bond, yielding the two halves as their own separate nitriles.

It seems to be a reasonable reaction, and someone may well find a use for it. I just enjoyed it because it was totally outside the way that I think about breaking and forming bonds. And it makes me wonder about the reverse: will someone find a way to take two nitriles and turn them into a linked alkyne? Formally, that gives off nitrogen, so you'd think that there would be some way to make it happen. . .

Comments (9)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Chemical News

Posted by Derek

FiercePharma has some good figures to back up my posts the other day on R&D; spending versus marketing. I mentioned how many people, when they argue that drug companies spend more on marketing than they do on research, are taking the entire SG&A; number, and how companies tend to not even break out their marketing numbers at all.

Well, the folks at Fierce had a recent article on marketing budgets in the business, and they take Pfizer's numbers as a test case. That's actually a really good example: Pfizer is known as a mighty marketing machine, and for a long time they had what must have been the biggest sales force in the industry. They also have a lower R&D; spend than many of their peers, as a percentage of sales. So if you're looking for the sort of skewed priorities that critics are always complaining about, here's where you'd look.

Pfizer spent $622 million on advertising last year. Man, that's a lot of money. It's so much that it's not even one-tenth of their R&D; budget. Ah, you say, but ads are only part of the story, and so they are. But while we don't have a good estimate on that for Pfizer, we do have one for the industry as a whole:

DTC spending is only part of the overall sales-and-marketing budget, of course. Detailing to doctors costs a pretty penny, and that's where drugmakers spend much of their sales budget. Consumer advertising spending dropped by 11.5% in 2012 to $3.47 billion. Marketing to physicians, according to a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health study, amounted to $27.7 billion in 2010; that same year, DTC spending was just over $4 billion.

That's a total for 2010 of more than $31 billion, the best guess-timate we can come up with on short notice. According to FierceBiotech's 2010 R&D; spending report, the industry shelled out $67 billion on research that year--more than twice our quick-and-dirty marketing estimate.

So let's try for a Pfizer estimate then. If they stayed at roughly that ratio, then they would have spent seven times as much marketing to physicians as they did on advertising per se. That gives a rough number of $4.3 billion, plus that $622 million, for a nice round five billion dollars of marketing. That's still less than their R&D; budget of $7.9 billion, folks, no small sum. (And as for that figure from a couple of years ago about how it only costs $43 million to find a new drug, spare me. Spare everyone. Pfizer is not allocating $7.9 billion dollars for fun, nor are they planning on producing 184 new drugs with that money at $43 million per, more's the pity.)

So let me take a stronger line: Big Pharma does not spend more on marketing than it does on R&D.; This is a canard; it's not supported by the data. And let me reiterate a point that's been made here several times: no matter what the amount spent on marketing, it's supposed to bring in more money than is spent. That's the whole point of marketing. Even if the marketing budget was the same as the R&D;, even if it were more, it still wouldn't get rid of that point: the money that's being spent in the labs is money that came in because of marketing. Companies aren't just hosing away billions of dollars on marketing because they enjoy it; they're doing it to bring in a profit (you know, that more-money-than-you-spend thing), and if some marketing strategy doesn't look like it's performing, it gets ditched. The response-time loop over there is a lot tighter than it is in research.

There. Now the next time this comes up, I'll have a post to point to, with the numbers, and with the links. It will do no good at all.

Note: I am not saying that every kind of drug company marketing is therefore good. Nor am I saying that I do not cringe and roll my eyes at some of it. And yes indeed, companies can and do cross lines that shouldn't be crossed when they get to selling their products too hard. Direct-to-consumer advertising, although it has brought in the money, has surely damaged the industry from other directions. All this is true. But the popular picture of big drug companies as huge advertising shops with little vestigial labs stuck to them: that isn't.

Comments (29)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Why Everyone Loves Us

May 22, 2013

Posted by Derek

A conversation the other day about 2-D NMR brought this thought to mind. What do you think are the most underused analytical methods in organic chemistry? Maybe I should qualify that, to the most underused (but potentially useful) ones.

I know, for example, that hardly anyone takes IR spectra any more. I've taken maybe one or two in the last ten years, and that was to confirm the presence of things like alkynes or azides, which show up immediately and oddly in the infrared. Otherwise, IR has just been overtaken by other methods for many of its application in organic chemistry, and it's no surprise that it's fallen off so much since its glory days. But I think that carbon-13 NMR is probably underused, as are a lot of 2D NMR techniques. Any other nominations?

Comments (58)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Analytical Chemistry | Life in the Drug Labs

Posted by Derek

Just how many different small-molecule binding sites are there? That's the subject of this new paper in PNAS, from Jeffrey Skolnick and Mu Gao at Georgia Tech, which several people have sent along to me in the last couple of days.

This question has a lot of bearing on questions of protein evolution. The paper's intro brings up two competing hypotheses of how protein function evolved. One, the "inherent functionality model", assumes that primitive binding pockets are a necessary consequence of protein folding, and that the effects of small molecules on these (probably quite nonspecific) motifs has been honed by evolutionary pressures since then. (The wellspring of this idea is this paper from 1976, by Jensen, and this paper will give you an overview of the field). The other way it might have worked, the "acquired functionality model", would be the case if proteins tend, in their "unevolved" states, to be more spherical, in which case binding events must have been much more rare, but also much more significant. In that system, the very existence of binding pockets themselves is what's under the most evolutionary pressure.

The Skolnick paper references this work from the Hecht group at Princeton, which already provides evidence for the first model. In that paper, a set of near-random 4-helical-bundle proteins was produced in E. coli - the only patterning was a rough polar/nonpolar alternation in amino acid residues. Nonetheless, many members of this unplanned family showed real levels of binding to things like heme, and many even showed above-background levels of several types of enzymatic activity.

In this new work, Skolnick and Gao produce a computational set of artificial proteins (called the ART library in the text), made up of nothing but poly-leucine. These were modeled to the secondary structure of known proteins in the PDB, to produce natural-ish proteins (from a broad structural point of view) that have no functional side chain residues themselves. Nonetheless, they found that the small-molecule-sized pockets of the ART set actually match up quite well with those found in real proteins. But here's where my technical competence begins to run out, because I'm not sure that I understand what "match up quite well" really means here. (If you can read through this earlier paper of theirs at speed, you're doing better than I can). The current work says that "Given two input pockets, a template and a target, (our algorithm) evaluates their PS-score, which measures the similarity in their backbone geometries, side-chain orientations, and the chemical similarities between the aligned pocket-lining residues." And that's fine, but what I don't know is how well it does that. I can see poly-Leu giving you pretty standard backbone geometries and side-chain orientations (although isn't leucine a little more likely than average to form alpha-helices?), but when we start talking chemical similarities between the pocket-lining residues, well, how can that be?

But I'm even willing to go along with the main point of the paper, which is that there are not-so-many types of small-molecule binding pockets, even if I'm not so sure about their estimate of how many there are. For the record, they're guessing not many more than about 500. And while that seems low to me, it all depends on what we mean by "similar". I'm a medicinal chemist, someone who's used to seeing "magic methyl effects" where very small changes in ligand structure can make big differences in binding to a protein. And that makes me think that I could probably take a set of binding pockets that Skolnick's people would call so similar as to be basically identical, and still find small molecules that would differentiate them. In fact, that's a big part of my job.

But in general, I see the point they're making, but it's one that I've already internalized. There are a finite number of proteins in the human body. Fifty thousand? A couple of hundred thousand? Probably not a million. Not all of these have small-molecule binding sites, for sure, so there's a smaller set to deal with right there. Even if those binding sites were completely different from one another, we'd be looking at a set of binding pockets in the thousands/tens of thousands range, most likely. But they're not completely different, as any medicinal chemist knows: try to make a selective muscarinic agonist, or a really targeted serine hydrolase inhibitor, and you'll learn that lesson quickly. And anyone who's run their drug lead through a big selectivity panel has seen the sorts of off-target activities that come up: you hit someof the other members of your target's family to greater or lesser degree. You hit the flippin' sigma receptor, not that anyone knows what that means. You hit the hERG channel, and good luck to you then. Your compound is a substrate for one of the CYP enzymes, or it binds tightly to serum albumin. Who has even seen a compound that binds only to its putative target? And this is only with the counterscreens we have, which is a small subset of the things that are really out there in cells.

And that takes me to my main objection to this paper. As I say, I'm willing to stipulate, gladly, that there are only so many types of binding pockets in this world (although I think that it's more than 500). But this sort of thing is what I have a problem with:

". . .we conclude that ligand-binding promiscuity is likely an inherent feature resulting from the geometric and physical–chemical properties of proteins. This promiscuity implies that the notion of one molecule–one protein target that underlies many aspects of drug discovery is likely incorrect, a conclusion consistent with recent studies. Moreover, within a cell, a given endogenous ligand likely interacts at low levels with multiple proteins that may have different global structures.

"Many aspects of drug discovery" assume that we're only hitting one target? Come on down and try that line out in a drug company, and be prepared for rude comments. Believe me, we all know that our compounds hit other things, and we all know that we don't even know the tenth of it. This is a straw man; I don't know of anyone doing drug discovery that has ever believed anything else. Besides, there are whole fields (CNS) where polypharmacy is assumed, and even encouraged. But even when we're targeting single proteins, believe me, no one is naive enough to think that we're hitting those alone.

Other aspects of this paper, though, are fine by me. As the authors point out, this sort of thing has implications for drawing evolutionary family trees of proteins - we should not assume too much when we see similar binding pockets, since these may well have a better chance of being coincidence than we think. And there are also implications for origin-of-life studies: this work (and the other work in the field, cited above) imply that a random collection of proteins could still display a variety of functions. Whether these are good enough to start assembling a primitive living system is another question, but it may be that proteinaceous life has an easier time bootstrapping itself than we might imagine.

Comments (16)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Biological News | In Silico | Life As We (Don't) Know It

May 21, 2013

Posted by Derek

Here's a man who says what he thinks about getting students into STEM careers:

The United States spent more than US$3 billion last year across 209 federal programmes intended to lure young people into careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). The money goes on a plethora of schemes at school, undergraduate and postgraduate levels, all aimed at promoting science and technology, and raising standards of science education.

In a report published on 10 April, Congress’s Government Accountability Office (GAO) asked a few pointed questions about why so many potentially overlapping programmes coexist. The same day, the 2014 budget proposal of President Barack Obama’s administration suggested consolidating the programmes, but increasing funding.

What no one asked was whether these many activities actually benefit science and engineering, or society as a whole. My answer to both questions is an emphatic ‘no’.

And I think he's right about that. Whipping and driving people into science careers doesn't seem like a very good way to produce good scientists. In fact, it seems like an excellent way to produce a larger cohort of indifferent ones, which is exactly what we don't need. Or does that depend on the definition of "we"?

The dynamic at work here isn’t complicated. By cajoling more children to enter science and engineering — as the United Kingdom also does by rigging university-funding rules to provide more support for STEM than other subjects — the state increases STEM student numbers, floods the market with STEM graduates, reduces competition for their services and cuts their wages. And that suits the keenest proponents of STEM education programmes — industrial employers and their legion of lobbyists — absolutely fine.

And that takes us back to the subject of these two posts, on the oft-heard complaints of employers that they just can't seem to find qualified people any more. To which add, all too often, ". . .not at the salaries we'd prefer to pay them, anyway". Colin Macilwain, the author of this Nature piece I'm quoting from, seems to agree:

But the main backing for government intervention in STEM education has come from the business lobby. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard a businessman stand up and bemoan the alleged failure of the education system to produce the science and technology ‘skills’ that his company requires, I’d be a very rich man.

I have always struggled to recognize the picture these detractors paint. I find most recent science graduates to be positively bursting with both technical knowledge and enthusiasm.

If business people want to harness that enthusiasm, all they have to do is put their hands in their pockets and pay and train newly graduated scientists and engineers properly. It is much easier, of course, for the US National Association of Manufacturers and the British Confederation of British Industry to keep bleating that the state-run school- and university-education systems are ‘failing’.

This position, which was not my original one on this issue, is not universally loved. (The standard take on this issue, by contrast, has the advantage of both flattering and advancing the interests of employers and educators alike, and it's thus very politically attractive). I don't even have much affection for my own position on this, even though I've come to think it's accurate. As I've said before, it does feel odd for me, as a scientist, as someone who values education greatly, and as someone who's broadly pro-immigration, to be making these points. But there they are.

Update: be sure to check the comments section if this topic interests you - there are a number of good ones coming in, from several sides of this issue.

Comments (74)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Current Events

May 20, 2013

Posted by Derek

So drug companies may spend a lot on R&D;, but they spend even more on marketing, right? I see the comments are already coming in to that effect on this morning's post on R&D; expenditures as a percentage of revenues. Let's take a look at those other numbers, then.

We're talking SG&A;, "sales, general, and administrative". That's the accounting category where all advertising, promotion and marketing ends up. Executive salaries go there, too, in case you're wondering. Interestingly, R&D; expenses technically go there as well, but companies almost always break that out as a separate subcategory, with the rest as "Other SG&A;". What most companies don't do is break out the S part separately: just how much they spend on marketing (and how, and where) is considering more information than they're willing to share with the world, and with their competition.

That means that when you see people talking about how Big Pharma spends X zillion dollars on marketing, you're almost certainly seeing an argument based on the whole SG&A; number. Anything past that is a guess - and would turn out to be a lower number than the SG&A;, anyway, which has some other stuff rolled into it. Most of the people who talk about Pharma's marketing expenditures are not interested in lower numbers, anyway, from what I can see.

So we'll use SG&A;, because that's what we've got. Now, one of the things you find out quickly when you look at such figures is that they vary a lot, from industry to industry, and from company to company inside any given group. This is fertile ground for consultants, who go around telling companies that if they'll just hire them, they can tell them how to get their expenses down to what some of their competition can, which is an appealing prospect.

Here you see an illustration of that, taken from the web site of this consulting firm. Unfortunately, this sample doesn't include the "Pharmaceuticals" category, but "Biotechnology" is there, and you can see that SG&A; as a percent of revenues run from about 20% to about 35%. That's definitely not one of the low SG&A; industries (look at the airlines, for example), but there are a lot of other companies, in a lot of other industries, in that same range.

So, what do the SG&A; expenditures look like for some big drug companies? By looking at 2012 financials, we find that Merck's are at 27% of revenues, Pfizer is at 33%, AstraZeneca is just over 31%, Bristol-Myers Squibb is at 28%, and Novartis is at 34% high enough that they're making special efforts to talk about bringing it down. Biogen's SG&A; expenditures are 23% of revenues, Vertex's are 29%, Celgene's are 27%, and so on. I think that's a reasonable sample, and it's right in line with that chart's depiction of biotech.

What about other high-tech companies? I spent some time in the earlier post talking about their R&D; spending, so here are some SG&A; figures. Microsoft spends 25%, Google just under 20%, and IBM spends 21.5%. Amazon's expenditures are about 23%, and have been climbing. But many other tech companies come in lower: Hewlett-Packard's SG&A; layouts are 11% of revenues, Intel's are 15%, Broadcom's are 9%, and Apple's are only 6.5%.

Now that's more like it, I can hear some people saying. "Why can't the drug companies get their marketing and administrative costs down? And besides, they spend more on that than they do on research!" If I had a dollar for every time that last phrase pops up, I could take the rest of the year off. So let's get down to what people are really interested in: sales/administrative costs versus R&D.; Here comes a list (and note that some of the figures may be slightly off this morning's post - different financial sites break things down slightly differently):

Merck: SG&A; 27%, R&D; 17.3%

Pfizer: SG&A; 33%, R&D; 14.2%

AstraZeneca: SG&A; 31.4%, R&D; 15.1%

BMS: SG&A; 28%, R$D 22%

Biogen: SG&A; 23%, R&D; 24%

Johnson & Johnson: SG&A; 31%, R&D; 12.5%

Well, now, isn't that enough? As you go to smaller companies, it looks better (and in fact, the categories flip around) but when you get too small, there aren't any revenues to measure against. But jut look at these people - almost all of them are spending more on sales and administration than they are on research, sometimes even a bit more than twice as much! Could any research-based company hold its head up with such figures to show?

Sure they could. Sit back and enjoy these numbers, by comparison:

Hewlett-Packard: SG&A; 11%, R&D; 2.6%.

IBM: SG&A; 21.5%, R&D; 5.7%.

Microsoft: SG&A; 25%, R&D; 13.3%.

3M: SG&A; 20.4%, R&D; 5.5%

Apple: SG&A; 6.5%, R&D; 2.2%.

GE: SG&A; 25%, R&D; 3.2%

Note that these companies, all of whom appear regularly on "Most Innovative" lists, spend anywhere from two to eight times their R&D; budgets on sales and administration. I have yet to hear complaints about how this makes all their research into some sort of lie, or about how much more they could be doing if they weren't spending all that money on those non-reseach activities. You cannot find a drug company with a split between SG&A; and research spending like there is for IBM, or GE, or 3M. I've tried. No research-driven drug company could survive if it tried to spend five or six times its R&D; on things like sales and administration. It can't be done. So enough, already.

Note: the semiconductor companies, which were the only ones I could find with comparable R&D; spending percentages to the drug industry, are also outliers in SG&A; spending. Even Intel, the big dog of the sector, manages to spend slightly less on that category than it does on R&D;, which is quite an accomplishment. The chipmakers really are off on their own planet, financially. But the closest things to them are the biopharma companies, in both departments.

Comments (25)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Drug Industry History

Posted by Derek

How much does Big Pharma spend on R&D;, compared to what it takes in? This topic came up during a discussion here last week, when a recent article at The Atlantic referred to these expenditures as "only" 16 cents on the dollar, and I wanted to return to it.

One good source for such numbers is Booz, the huge consulting outfit, and their annual "Global Innovation 1000" survey. This is meant to be a comparison of companies that are actually trying to discover new products and bring them to market (as opposed to department stores, manufacturers of house-brand cat food, and other businesses whose operations consist of doing pretty much the same thing without much of an R&D; budget). Even among these 1000 companies, the average R&D; budget, as a per cent of sales, is between 1 and 1.5%, and has stayed in that range for years.

Different industries naturally have different averages. The "chemicals and energy" category in the Booz survey spends between 1 and 3% of its sales on R&D.; Aerospace and defense companies tend to spend between 3 and 6 per cent. The big auto makers tend to spend between 3 and 7% of their sales on research, but those sales figures are so large that they still account for a reasonable hunk (16%) of all R&D; expenditures. That pie, though, has two very large slices representing electronics/computers/semiconductors and biopharma/medical devices/diagnostics. Those two groups account for half of all the industrial R&D; spending in the world.

And there are a lot of variations inside those industries as well. Apple, for example, spends only 2.2% of its sales on R&D;, while Samsung and IBM come in around 6%. By comparison with another flagship high-tech sector, the internet-based companies, Amazon spends just over 6% itself, and Google is at a robust 13.6% of its sales. Microsoft is at 13% itself.

The semiconductor companies are where the money really gets plowed back into the labs, though. Here's a roundup of 2011 spending, where you can see a company like Intel, with forty billion dollars of sales, still putting 17% of that back into R&D.; And the smaller firms are (as you might expect) doing even more. AMD spends 22% of its sales on R&D;, and Broadcom spends 28%. These are people who, like Alice's Red Queen, have to run as fast as they can if they even want to stay in the same place.

Now we come to the drug industry. The first thing to note is that some of its biggest companies already have their spending set at Intel levels or above: Roche is over 19%, Merck is over 17%, and AstraZeneca is over 16%. The others are no slouches, either: Sanofi and GSK are above 14%, and Pfizer (with the biggest R&D; spending drop of all the big pharma outfits, I should add) is at 13.5%. They, J&J;, and Abbott drag the average down by only spending in the 11-to-14% range - I don't think that there's such a thing as a drug discovery company that spends in the single digits compared to revenue. If any of us tried to get away with Apple's R&D; spending levels, we'd be eaten alive.

All this adds up to a lot: if you take the top 20 biggest industrial R&D; spenders in the world, eight of them are drug companies. No other industrial sector has that many on the list, and a number of companies just missed making it. Lilly, for one, spent 23% of revenues on R&D;, and BMS spend 22%, as did Biogen.

And those are the big companies. As with the chip makers, the smaller outfits have to push harder. Where I work, we spent about 50% of our revenues on R&D; last year, and that's projected to go up. I think you'll find similar figures throughout biopharma. So you can see why I find it sort of puzzling that someone can complain about the drug industry as a whole "only" spending 16% of its revenues. Outside of semiconductors, nobody spends more

Comments (26)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Business and Markets | Drug Industry History

May 17, 2013

Posted by Derek

Compare and contrast. Here we have Krishnan Ramalingam, from Ranbaxy's Corporate Communications department, in 2006:

Being a global pharmaceutical major, Ranbaxy took a deliberate decision to pool its resources to fight neglected disease segments. . .Ranbaxy strongly felt that generic antiretrovirals are essential in fighting the world-wide struggle against HIV/AIDS, and therefore took a conscious decision to embark upon providing high quality affordable generics for patients around the world, specifically for the benefit of Least Developed Countries. . .Since 2001, Ranbaxy has been providing antiretroviral medicines of high quality at affordable prices for HIV/AIDS affected countries for patients who might not otherwise be able to gain access to this therapy.

And here we have them in an advertorial section of the South African Mail and Guardian newspaper, earlier this year:

Ranbaxy has a long standing relationship with Africa. It was the first Indian pharmaceutical company to set up a manufacturing facility in Nigeria, in the late 1970s. Since then, the company has established a strong presence in 44 of the 54 African countries with the aim of providing quality medicines and improving access. . .Ranbaxy is a prominent supplier of Antiretroviral (ARV) products in South Africa through its subsidiary Sonke Pharmaceuticals. It is the second largest supplier of high quality affordable ARV products in South Africa which are also extensively used in government programs providing access to ARV medicine to millions.

Yes, as Ranbaxy says on its own web site: "At Ranbaxy, we believe that Anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy is an essential tool in waging the war against HIV/AIDS. . .We estimate currently close to a million patients worldwide use our ARV products for their daily treatment needs. We have been associated with this cause since 2001 and were among the first generic companies to offer ARVs to various National AIDS treatment programmes in Africa. We were also responsible for making these drugs affordable in order to improve access. . ."

And now we descend from the heights. Here, in a vivid example of revealed preference versus stated preference, is what was really going on, from that Fortune article I linked to yesterday:

. . .as the company prepared to resubmit its ARV data to WHO, the company's HIV project manager reiterated the point of the company's new strategy in an e-mail, cc'ed to CEO Tempest. "We have been reasonably successful in keeping WHO from looking closely at the stability data in the past," the manager wrote, adding, "The last thing we want is to have another inspection at Dewas until we fix all the process and validation issues once and for all."

. . .(Dinesh) Thakur knew the drugs weren't good. They had high impurities, degraded easily, and would be useless at best in hot, humid conditions. They would be taken by the world's poorest patients in sub-Saharan Africa, who had almost no medical infrastructure and no recourse for complaints. The injustice made him livid.

Ranbaxy executives didn't care, says Kathy Spreen, and made little effort to conceal it. In a conference call with a dozen company executives, one brushed aside her fears about the quality of the AIDS medicine Ranbaxy was supplying for Africa. "Who cares?" he said, according to Spreen. "It's just blacks dying."

I have said many vituperative things about HIV hucksters like Matthias Rath, who have told patient in South Africa to throw away their antiviral medications and take his vitamin supplements instead. What, then, can I say about people like this, who callously and intentionally provided junk, labeled as what were supposed to be effective drugs, to people with no other choice and no recourse? If this is not criminal conduct, I'd very much like to know what is.

And why is no one going to jail? I'm suggesting jail as a civilized alternative to a barbaric, but more appealingly direct form of justice: shipping the people who did this off to live in a shack somewhere in southern Africa, infected with HIV, and having them subsist as best they can on the drugs that Ranbaxy found fit for their sort.

Comments (43)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Infectious Diseases | The Dark Side

May 16, 2013

Posted by Derek

Here's an excellent, detailed look from Fortune at how things went off the rails at Ranbaxy and their generic atorvastatin (Lipitor). The company has been hit by a huge fine, and no wonder. This will give you the idea:

On May 13, Ranbaxy pleaded guilty to seven federal criminal counts of selling adulterated drugs with intent to defraud, failing to report that its drugs didn't meet specifications, and making intentionally false statements to the government. Ranbaxy agreed to pay $500 million in fines, forfeitures, and penalties -- the most ever levied against a generic-drug company. (No current or former Ranbaxy executives were charged with crimes.) Thakur's confidential whistleblower complaint, which he filed in 2007 and which describes how the company fabricated and falsified data to win FDA approvals, was also unsealed. Under federal whistleblower law, Thakur will receive more than $48 million as part of the resolution of the case. . .

. . .(he says that) they stumbled onto Ranbaxy's open secret: The company manipulated almost every aspect of its manufacturing process to quickly produce impressive-looking data that would bolster its bottom line. "This was not something that was concealed," Thakur says. It was "common knowledge among senior managers of the company, heads of research and development, people responsible for formulation to the clinical people.

Lying to regulators and backdating and forgery were commonplace, he says. The company even forged its own standard operating procedures, which FDA inspectors rely on to assess whether a company is following its own policies. Thakur's team was told of one instance in which company officials forged and backdated a standard operating procedure related to how patient data are stored, then aged the document in a "steam room" overnight to fool regulators.

Company scientists told Thakur's staff that they were directed to substitute cheaper, lower-quality ingredients in place of better ingredients, to manipulate test parameters to accommodate higher impurities, and even to substitute brand-name drugs in lieu of their own generics in bioequivalence tests to produce better results."

You name it, it's probably there. Good thing the resulting generic drugs were cheap, eh? And I suppose these details render inoperative, as the Nixon staff used to say, the explanations that the company used to have about talk of such problems, that it was all the efforts of their big pharma competitors and some unscrupulous stock market types. (Whenever you see a company's CEO going on about a conspiracy to depress his company's share price, you should worry).

The whole article is well worth reading - your eyebrows are guaranteed to go up a few times. This whole affair has been a damaging blow to the whole offshore generics business, India's in particular, and does not help them wear their "Low cost drugs for the poor" halo any better. Not when your pills have glass particles in them along with (or instead of) the active ingredient. . .

Comments (26)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: The Dark Side

Posted by Derek

"Can you respond to this tripe?" asked one of the emails that sent along this article in The Atlantic. I responded that I was planning to, but that things were made more complicated by my being extensively quoted in said tripe. Anyway, here goes.

The article, by Brian Till of the New America Foundation, seems somewhat confused, and is written in a confusing manner. The title is "How Drug Companies Keep Medicine Out of Reach", but the focus is on neglected tropical diseases, not all medicine. Well, the focus is actually on a contested WHO treaty. But the focus is also on the idea of using prizes to fund research, and on the patent system. And the focus is on the general idea of "delinking" R&D; from sales in the drug business. Confocal prose not having been perfected yet, this makes the whole piece a difficult read, because no matter which of these ideas you're waiting to hear about, you end up having a long wait while you work your way through the other stuff. There are any number of sentences in this piece that reference "the idea" and its effects, but there is no sentence that begins with "Here's the idea"

I'll summarize: the WHO treaty in question is as yet formless. There is no defined treaty to be debated; one of the article's contentions is that the US has blocked things from even getting that far. But the general idea is that signatory states would commit to spending 0.01% of GDP on neglected diseases each year. Where this money goes is not clear. Grants to academia? Setting up new institutes? Incentives to commercial companies? And how the contributions from various countries are to be managed is not clear, either: should Angola (for example) pool its contributions with other countries (or send them somewhere else outright), or are they interested in setting up their own Angolan Institute of Tropical Disease Research?

The fuzziness continues. You will read and read through the article trying to figure out what happens next. The "delinking" idea comes in as a key part of the proposed treaty negotiations, with the reward for discovery of a tropical disease treatment coming from a prize for its development, rather than patent exclusivity. But where that money comes from (the GDP-linked contributions?) is unclear. Who sets the prize levels, at what point the money is awarded, who it goes to: hard to say.

And the "Who it goes to" question is a real one, because the article says that another part of the treaty would be a push for open-source discovery on these diseases (Matt Todd's malaria efforts at Sydney are cited). This, though, is to a great extent a whole different question than the source-of-funds one, or the how-the-prizes-work one. Collaboration on this scale is not easy to manage (although it might well be desirable) and it can end up replacing the inefficiencies of the marketplace with entirely new inefficiencies all its own. The research-prize idea seems to me to be a poor fit for the open-collaboration model, too: if you're putting up a prize, you're saying that competition between different groups will spur them on, which is why you're offering something of real value to whoever finishes first and/or best. But if it's a huge open-access collaboration, how do you split up the prize, exactly?

At some point, the article's discussion of delinking R&D; and the problems with the current patent model spread fuzzily outside the bounds of tropical diseases (where there really is a market failure, I'd say) and start heading off into drug discovery in general. And that's where my quotes start showing up. The author did interview me by phone, and we had a good discussion. I'd like to think that I helped emphasize that when we in the drug business say that drug discovery is hard, that we're not just putting on a show for the crowd.

But there's an awful lot of "Gosh, it's so cheap to make these drugs, why are they so expensive?" in this piece. To be fair, Till does mention that drug discovery is an expensive and risky undertaking, but I'm not sure that someone reading the article will quite take on board how expensive and how risky it is, and what the implications are. There's also a lot of criticism of drug companies for pricing their products at "what the market will bear", rather than as some percentage of what it cost to discover or make them. This is a form of economics I've criticized many times here, and I won't go into all the arguments again - but I will ask:what other products are priced in such a manner? Other than what customers will pay for them? Implicit in these arguments is the idea that there's some sort of reasonable, gentlemanly profit that won't offend anyone's sensibilities, while grasping for more than that is just something that shouldn't be allowed. But just try to run an R&D-driven; business on that concept. I mean, the article itself details the trouble that Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and others are facing with their patent expirations. What sort of trouble would they be in if they'd said "No, no, we shouldn't make such profits off our patented drugs. That would be indecent." Even with those massive profits, they're in trouble.

And that brings up another point: we also get the "Drug companies only spend X pennies per dollar on R&D;". That's the usual response to pointing out situations like Lilly's; that they took the money and spent it on fleets of yachts or something. The figure given in the article is 16 cents per dollar of revenue, and it's prefaced by an "only". Only? Here, go look at different industries, around the world, and find one that spends more. By any industrial standard, we are plowing massive amounts back into the labs. I know that I complain about companies doing things like stock buybacks, but that's a complaint at the margin of what is already pretty impressive spending.

To finish up, here's one of the places I'm quoted in the article:

I asked Derek Lowe, the chemist and blogger, for his thoughts on the principle of delinking R&D; from the actual manufacture of drugs, and why he thought the industry, facing such a daunting outlook, would reject an idea that could turn fallow fields of research on neglected diseases into profitable ones. "I really think it could be viable," he said. "I would like to see it given a real trial, and neglected diseases might be the place to do it. As it is, we really already kind of have a prize model in the developed countries, market exclusivity. But, at the same time, you could look at it and it will say, 'You will only make this amount of money and not one penny more by curing this tropical disease.' Their fear probably is that if that model works great, then we'll move on to all the other diseases."

What you're hearing is my attempt to bring in the real world. I think that prizes are, in fact, a very worthwhile thing to look into for market failures like tropical diseases. There are problems with the idea - for one thing, the prize payoff itself, compared with the time and opportunity cost, is hard to get right - but it's still definitely worth thinking about. But what I was trying to tell Brian Till was that drug companies would be worried (and rightly) about the extension of this model to all other disease areas. Wrapped up in the idea of a research-prize model is the assumption that someone (a wise committee somewhere) knows just what a particular research result is worth, and can set the payout (and afterwards, the price) accordingly. This is not true.

There's a follow-on effect. Such a wise committees might possibly feel a bit of political pressure to set those prices down to a level of nice and cheap, the better to make everyone happy. Drug discovery being what it is, it would take some years before all the gears ground to a halt, but I worry that something like this might be the real result. I find my libertarian impulses coming to the fore whenever I think about this situation, and that prompts me to break out an often-used quote from Robert Heinlein:

Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances which permit this norm to be exceeded — here and there, now and then — are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of a society, the people then slip back into abject poverty.

This is known as "bad luck."

Comments (44)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Drug Development | Drug Prices | Why Everyone Loves Us

May 15, 2013

Posted by Derek

I was talking with someone the other day about the most difficult targets and therapeutic areas we knew, and that brought up the question: which of these has had the greatest number of clinical failures? Sepsis was my nomination: I know that there have been several attempts, all of which have been complete washouts. And for mechanisms, defined broadly, I nominate PPAR ligands. The only ones to make it through were the earliest compounds, discovered even before their target had been identified. What other nominations do you have?

Comments (32)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Clinical Trials | Drug Industry History

Posted by Derek

Speaking about open-source drug discovery (such as it is) and sharing of data sets (such as they are), I really should mention a significant example in this area: the GSK Published Kinase Inhibitor Set. (It was mentioned in the comments to this post). The company has made 367 compounds available to any academic investigator working in the kinase field, as long as they make their results publicly available (at ChEMBL, for example). The people at GSK doing this are David Drewry and William Zuercher, for the record - here's a recent paper from them and their co-workers on the compound set and its behavior in reporter-gene assays.

Why are they doing this? To seed discovery in the field. There's an awful lot of chemical biology to be done in the kinase field, far more than any one organization could take on, and the more sets of eyes (and cerebral cortices) that are on these problems, the better. So far, there have been about 80 collaborations, mostly in Europe and North America, all the way from broad high-content phenotypic screening to targeted efforts against rare tumor types.

The plan is to continue to firm up the collection, making more data available for each compound as work is done on them, and to add more compounds with different selectivity profiles and chemotypes. Now, the compounds so far are all things that have been published on by GSK in the past, obviating concerns about IP. There are, though, a multitude of other compounds in the literature from other companies, and you have to think that some of these would be useful additions to the set. How, though, does one get this to happen? That's the stage that things are in now. Beyond that, there's the possibility of some sort of open network to optimize entirely new probes and tools, but there's plenty that could be done even before getting to that stage.

So if you're in academia, and interested in kinase pathways, you absolutely need to take a look at this compound set. And for those of us in industry, we need to think about the benefits that we could get by helping to expand it, or by starting similar efforts of our own in other fields. The science is big enough for it. Any takers?

Comments (20)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Academia (vs. Industry) | Biological News | Chemical News | Drug Assays

May 14, 2013

Posted by Derek

I mentioned Microryza in that last post. Here's Prof. Michael Pirrung, at UC Riverside, with an appeal there to fund the resynthesis of a compound for NCI testing against renal cell carcinoma. It will provide an experienced post-doc's labor for a month to prepare an interesting natural-product-derived proteasome inhibitor that the NCI would like to take to their next stage of evaluation. Have a look - you might be looking at the future of academic research funding, or at least a real part of it.

Comments (14)

+ TrackBacks (0) | Category: Cancer | General Scientific News

Posted by Derek

Crowdfunding academic research might be changing, from a near-stunt to an widely used method of filling gaps in a research group's money supply. At least, that's the impression this article at Nature Jobs gives:

The practice has exploded in recent years, especially as success rates for research-grant applications have fallen in many places. Although crowd-funding campaigns are no replacement for grants — they usually provide much smaller amounts of money, and basic research tends to be less popular with public donors than applied sciences or arts projects — they can be effective, especially if the appeals are poignant or personal, involving research into subjects such as disease treatments.

The article details several venues that have been used for this sort of fund-raising, including Indiegogo, Kickstarter, RocketHub, FundaGeek, and SciFund Challenge. I'd add Microryza to that list. And there's a lot of good advice for people thinking about trying it themselves, including how much money to try for (at least at first), the timelines one can expect, and how to get your message out to potential donors.

Overall, I'm in favor of this sort of thing, but there are some potential problems. This gives the general pubic a way to feel more connected to scientific research, and to understand more about what it's actually like, both of which are goals I feel a close connection to. But (as that quote above demonstrates), some kinds of research are going to be an easier sell than others. I worry about a slow (or maybe not so slow) race to the bottom, with lab heads overpromising what their research can deliver, exaggerating its importance to immediate human concerns, and overselling whatever results come out.

These problems have, of course, been noted. Ethan Perlstein, formerly of Princeton, used RocketHub for his crowdfunding experiment that I wrote about here. And he's written at Microryza with advice about how to get the word out to potential donors, but that very advice has prompted a worried response over at SciFund Challenge, where Jai Ranganathan had this to say:

His bottom line? The secret is to hustle, hustle, hustle during a crowdfunding campaign to get the word out and to get media attention. With all respect to Ethan, if all researchers running campaigns follow his advice, then that’s the end for science crowdfunding. And that would be a tragedy because science crowdfunding has the potential to solve one of the key problems of our time: the giant gap between science and society.