A small Spring Thing this year. There was one game that I liked fairly well, and two that I didn't like enough to finish.

Witch's Girl, Geoff Moore, Twine

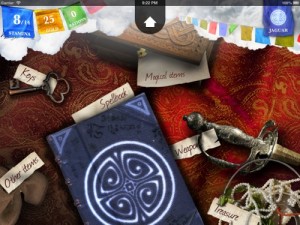

This is a Twine game: browser-based CYOA with some light state-tracking. It's well outside the Anna Anthropy style that's become near-synonymous with the platform, though; it eschews the grimy, retro, nocturnal, Robb Sherwiny white-on-black default for black-on-white and cute, simple illustrations, suggesting a children's book.

The story itself follows a young girl and her best friend on a fantasy adventure to save the world, of the familiar variety that involves collecting equipment and plot tokens, with a central journey thread; in overall shape it looks like a Fighting Fantasy kind of story, minus the fiddly details of combat. Links are presented in the 'if X, turn to page Y' format. This reinforces the conceit of an illustrated book, but I don't feel that this is taken quite far enough to hold together; a more print-like font would have gone a long way here.

We're firmly in Worst Witch / Harry Potter territory. The main character's name is Oblivia (definitely points there), and the whole thing has a heavy dose of lampshading. We're in fantasyland, but it's a very English fantasyland. On the one hand, we have

chums,

the hols,

apple-scrumping, all things which I'm pretty sure ceased to exist at some point in the seventies. On the other, perms are common enough that small children have them (suggesting the 80s). Which, ah, suggests an author of a very specific generation, fairly close to mine, for whom the 80s are the Land of Small Childhood and thus blurred into a sort of gumbo Penny Lane English nostalgia with Oram & Kitamura and Molesworth and Just William and Five Children and It.

Although it's larger than you'd expect of a Twine game, it has a certain feeling of hurriedness; there's the sense, more or less, that you already know this kind of story, so there's no point in doing every scene thoroughly. You get similar effects with Asylum movies, or with the Kingdom of Loathing, in which every story element is self-consciously a knockoff from other stories and thus can be handwaved. Oblivia and Esme frequently get sort of distracted from saving the world and have to be shepherded back on track by the titular witch; in one sense this is because they're both regarding it as a sort of game, but in another it's because the whole story, like

a bunch of other CYOA, operates through the lens of millenial snark. Yeah yeah, save the world, we know that tune. Because of this I found it difficult, despite its simplicity and gentleness, to think of it as an actual children's story, rather than a grown-up story packaged as kidlit. The story does a good job of depicting the uncomplicated friendship between Esme and Oblivia, and there are some individual scenes that felt just right; on the larger scale, though, the world and story don't feel of a piece, as though the author didn't quite trust them. (I'm reminded of Terry Jones' children's stories, which at times have a similar basic feeling of snarky mistrust in the basic matter of story.)

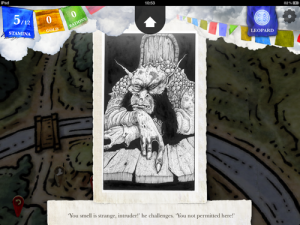

Again, there are illustrations, and they are just right for the story's tone: simple, charming, a little snarky. They add to the work - particularly one's sense of the characters - without dominating it. My main complaint is that it'd be nice if there had been more of them, which is the most complimentary complaint I know of.

The story is fairly linear as CYOA goes, with one central trunk and lots of short branches that reconnect to it. It's made more so because, at around the halfway point, you discover a time-travel device that can drop you off at any major story node that you've already encountered. (Time-travel has always been a big theme of CYOA; the medium seems to automatically suggest it.) Using it a lot is pretty much mandatory, because you require a lot of items, knowledge tokens and so forth to overcome the obstacles of the central plot and advance the story into new areas - and getting everything you need is not possible on a straight playthrough. Unlike, say,

Time Machine; Secret of the Knights, the point of time-travel isn't to return you to the One True Path, which you could have stayed on the whole time if only you'd chosen correctly; the story requires you to go everywhere and do everything. (Well, nearly.)

I have a few minor complaints, mostly derived from the time-looping core mechanic. There is no way of checking inventory, which I wanted to do rather often (if nothing else, it'd be a list of loose ends that still needed clearing up). Similarly, nodes that showed you gaining an object didn't change if you've already acquired that object. (So do objects vanish when you go back in time? Apparently not, because you can go back in time, fail to get an object you've already acquired, but still use it later on in the same playthrough.) The epilogue seems to assume that you've exhausted every possible node, but I'm pretty sure that this isn't necessary to win, and some events were referenced that I had never encountered. So it'd be nice to see the logic here tidied up a little.

Finally, the looping structure strongly encourages lawnmowering. This is a mixed blessing; it means that you see a pretty high proportion of the content without replaying, but it also means that you repeat through the same text a lot, eyes glazed over.

A Roiling Original, Andrew Schultz, Glulx

This is a sequel to the anagram-based wordplay game from IF Comp 2012

Shuffling Around, and delivers a very similar experience. Once again, it offers a good deal of brain-puzzly fun, but for my tastes there's not enough narrative or IF-gameplay-like content to distinguish it from a series of pen-and-paper anagram puzzles. The puzzles I encountered don't really build on one another; they're isolates, and once you've solved enough of them you move on to doing some more.

If you are into this sort of thing, it is the sort of thing you will be into. I mean, I say that a lot, but this is very true of

A Roiling Original. It's catering to a specific taste, has a laser-like focus on it, and everything else is sort of off in the distance.

Personally, I need a bit more to keep me going: either a more sustained, less piecemeal puzzle mechanic, or more coherent narrative and character stuff. (Or, ideally,

both.) I think, though, that even within the limits of wordplay-driven wackiness,

A Roiling Original could have been a good deal more readable. As things stand, the prose is thick with throwaway anagrams that slow down comprehension without adding information: my impression was that the design process of the game involved coming up with many, many anagrams, and then finding a place for them in the text

somewhere, even if not as a puzzle.

This often makes sentences read as though they've been run through a translation program a few times: on the first scan it's just a sort of nonsense-verse. I found that this made negotiating the text a chore: I'd have to parse a bunch of garbly English to get to some rather weird information, and then work out whether that information was relevant to the plot or just the product of garbles, and then figure out which part of the jumble was an important, interactive anagram and which were just flavour. This isn't a fantastical world on the order of the

Alice books or

The Phantom Tollbooth; it's more about the twistiness and less about the world.

So ultimately, this is fairly slow going and I'm just not enough of a pure puzzler to make it worth it.

Encyclopedia of Elementals, Adam Holbrook, Quest

This is a game with heavy, conspicuous CRPG influences: it's stock genre fantasy, characters give you miniquests for gold, there is magic and clashing kingdoms and hints of a Hidden Chosen One plot. My impression was that it isn't hugely interested in challenging the boundaries of its well-established genre: it's setting out to be an iteration of an established form. This is not inherently a bad thing; working on doing a good job at something familiar can be a worthy undertaking.

I see two big problems, though: one is to do with my personal taste, the other isn't. Let's get the personal part out of the way first. My personal feeling is that the territory of fantasy CRPG and its adjacent forms are worn out. It's a genre that's slowly been watered down into a homogenous, flavourless mulch, and unless someone finds a really great way to spice it up again, it bores me to tears. Now I'm very happy indeed to consume things that push and twist at the edges of the territory, or that stake out a claim on an underfrequented portion of it and make it theirs. I'm all about

Kerkerkruip or

Treasures of a Slaver's Kingdom, or for that matter

Planescape:Torment or

Polaris or China Mieville or

Chalion. But put me in front of

Baldur's Gate or

The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion or the

Game of Thrones books and I fucking weep with boredom. If something's uninterested in pushing at the assumptions of genre fantasy, it has to provide a really, really high-quality experience to hold me.

The other big problem, which I think is a more general one, is that CRPGs are not typically an all-text form: they deliver much of their information through graphics and audio, with text often functioning in an auxiliary role. When text moves into a central role, it has to do more work and it has to do it better. The writing in

Encyclopedia of Elementals wouldn't be particularly bad if it was serving an auxiliary role in a graphical CRPG, but in an all-text medium it's not doing nearly enough. I think that this pressure on the text becomes greater in CYOA, where the text has less support from the world model.

Often these two issues overlap. For instance, a traditional focus of genre fantasy is detail-oriented, encylopaedic worldbuilding. At its worst this is plodding Jaggedy Mountains/Wiggly River stuff; at its best it creates rich, evocative landscapes, complex, living cultures, and a strong sense of the narrative's grounding in a memorable world.

Encyclopedia of Elementals doesn't spend much time on any of this: we start in a stock castle outside a stock town. Of the two nations mentioned, one doesn't get a name. We're given little idea of setting elements like landscape and culture. The NPCs have strongly mundane real-world names - Dave, Steve, Sheila - except for the ones who don't, like Hephaistos. We know that we're an apprentice wizard, a hostage/slave, and a foreigner - but there's no suggestion of the kind of implications those social categories convey.

In fact, the game is not generally good at delivering information. The introductory sequence, in which you wake up late at night and walk through a castle straight to a secret library, makes it rather unclear whether you knew about the library already. But this sort of plot confusion is less important than the failure to convinvingly deliver the kind of information that makes a story engaging, to identify what's cool about the piece and deliver it to the audience. Perhaps the thing that the author really cares about shows up later in the story; but for CYOA, the plot doesn't get you there in a very smooth or efficient manner.

At length some backstory is delivered (via a textdump that has some serious problems with using second-person dialogue smoothly):

You tell him that the nation you come from was being conquered by the nation you are in, Hinton. By the terms of peace, you were given to Hinton to be a resident and to serve in the castle. You tell the man that you don't know why you were offered up, because up until that point you had only been considered a novice mage, and you alone were surrendered to stop the war.

(We don't call that a

resident, dude. We call those hostages or slaves.) So, okay, we're a Chosen One of some sort. There is some CRPG-ish mini-questing, plus some old-school IF-ish take-everything-in-case-it-may-one-day-become-useful. There is very little in the way of explanation for why you're doing stuff; you do chore-quests to earn money, but it's not clear what you would actually spend money on and why. This sort of prevarication can be offset a bit if the player is presented by shiny things in the meantime, so more engaging writing or setting or characters could have helped here, but really it just needs to get down to it. The title and introduction suggest that the central interest of the story is going to be about elemental magic: but you're told almost nothing about that subject, and after the intro you go into a sequence of dull and apparently unrelated miniquests.

Here's the central failing of

Encyclopedia of Elementals, the big thing I'd advise this author to work on: it's too generic for too long. For writing to come alive, it needs to have flavour. Why is this secret passage, this blacksmith's forge, this fantasy nation more interesting than the vague concept that I already have of what a secret passage or forge or fantasy nation is? Or, if you're not interested in forge design, what

are you interested in? What's the central cool thing that this game's meant to deliver, and how quickly can you get to the part of the story where that starts kicking in?