Aripiprazole

|

|

|---|---|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 7-{4-[4-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butoxy}-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Abilify |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603012 |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | C (USA) |

| Legal status | ℞ Prescription only |

| Routes | Oral (via tablets, orodispersable tablets, and oral solution); intramuscular |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 87% |

| Protein binding | >99% |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Half-life | 75 hours (active metabolite is 94 hours) |

| Excretion | Feces and urine |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 129722-12-9 |

| ATC code | N05AX12 |

| PubChem | CID 60795 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 34 |

| DrugBank | DB01238 |

| ChemSpider | 54790 |

| UNII | 82VFR53I78 |

| KEGG | D01164 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:31236 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1112 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C23H27Cl2N3O2 |

| Mol. mass | 448.385 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Aripiprazole (pron.: /ˌɛərɨˈpɪprəzoʊl/ AIR-i-PIP-rə-zohl; brand names: Abilify, Aripiprex) is a partial dopamine agonist of the second generation class of atypical antipsychotics with additional antidepressant properties that is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and clinical depression. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for schizophrenia on November 15, 2002 and the European Medicines Agency on 4 June 2004; for acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder on October 1, 2004; as an adjunct for major depressive disorder on November 20, 2007; and to treat irritability in children with autism on 20 November 2009.[1][2] Aripiprazole was developed by Otsuka in Japan, and in the United States, Otsuka America markets it jointly with Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Contents |

[edit] Medical uses

Aripiprazole is used for the treatment of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[3]

In the United States, the FDA has approved aripiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults and adolescents (aged 13–17), of manic and mixed episodes associated with Bipolar I Disorder with or without psychotic features in adults, children and adolescents (aged 10–17),[4] of irritability associated with autism in pediatric patients (aged 6–17),[5] and of depression when used along with antidepressants in adults.[6]

Aripiprazole is also used off-label for schizophrenia in children (aged 10–12), and to treat dementia-related psychosis in geriatric patients, though Bristol-Myers Squibb was penalized for promoting such uses in the United States.[7]

[edit] Bipolar disorder

Aripiprazole has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute manic and mixed episodes, in both pediatric patients aged 10–17 and in adults.[8] Several double-blind, placebo-controlled trials support this use.[9][10][11][12] In addition, it is often used as maintenance therapy, either on its own or in conjunction with a mood stabilizer such as lithium or valproate. This use is also supported by a handful of studies.[13][14] Aripiprazole is at least as effective as haloperidol at reducing manic symptoms,[15][unreliable source?] and is much better tolerated by patients.[16]

Aripiprazole's use as a monotherapy in bipolar depression is more controversial. While a few pilot studies have found some effectiveness[17][18] (with one finding a reduction in anhedonia symptoms[19]), two large, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies found no difference between aripiprazole and placebo.[20] One study reported depression as a side effect of the drug.[21]

[edit] Major depression

In 2007, aripiprazole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of unipolar depression when used adjunctively with an antidepressant medication.[22] It has not been FDA-approved for use as monotherapy in unipolar depression.

[edit] Autism

In 2009, the United States FDA approved aripiprazole to treat irritability in "children and adolescents ages 6 to 17 years old" who have been diagnosed with autism.[23] It was approved on the basis of two studies that showed it reduced aggression towards others, self-injury, quickly changing moods, and irritability.

[edit] Cocaine dependency

Perhaps owing to its mechanism of action relating to dopamine receptors, there is some evidence to suggest that aripiprazole blocks cocaine-seeking behavior in animal models without significantly affecting other rewarding behaviors (such as food self-administration).[24]

[edit] Methamphetamine dependency

The book Addiction Medicine mentions studies, suggesting aripiprazole would be counter-therapeutic as treatment for methamphetamine dependency because it increased methamphetamine's stimulant and euphoric effects, and increased the baseline level of desire for methamphetamine. The author mentions studies that suggest that dopamine agonist treatment would be counter-therapeutic for methamphetamine/amphetamine dependency.[25]

[edit] Side effects

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

[edit] Common side effects in adults

- nausea

- vomiting

- constipation

- headache

- dizziness

- inner sense of restlessness/need to move (akathisia)

- anxiety

- insomnia

- restlessness[26]

[edit] Common side effects in children

- feeling sleepy

- headache

- vomiting

- fatigue

- increased appetite

- insomnia

- nausea

- stuffy nose

- weight gain

- uncontrolled movement such as restlessness, tremor muscle stiffness [27]

[edit] Infrequent

- Uncontrollable twitching or jerking movements, tremors, seizure, and weight gain. Some people may feel dizzy, especially when getting up from a lying or sitting position, or may experience a fast heart rate.

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Combination of fever, muscle stiffness, faster breathing, sweating, reduced consciousness, and sudden change in blood pressure and heart rate.)

- Suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts

- Painful and/or sustained erection (Priapism)

- Tardive dyskinesia (As with all antipsychotic medication, patients using aripiprazole may develop the permanent neurological disorder tardive dyskinesia.[28][29][30])

- Stroke (While taking aripiprazole some elderly patients with dementia have suffered from stroke or 'mini' stroke.)

- Allergic reaction (such as swelling in the mouth or throat, itching, rash), speech disorder, nervousness, agitation, fainting, reports of abnormal liver test values, inflammation of the pancreas, muscle pain, weakness, stiffness, or cramps.

- Sudden unexplained death[31]

[edit] Discontinuation

Aripiprazole should be discontinued gradually, with careful consideration from the prescribing doctor, to avoid withdrawal symptoms or relapse.

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing anti-psychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[32] Due to compensatory changes at dopamine, serotonin, adrenergic and histamine receptor sites in the central nervous system, withdrawal symptoms can occur during abrupt or over-rapid reduction in dosage. Withdrawal symptoms reported to occur after discontinuation of antipsychotics include nausea, emesis, lightheadedness, diaphoresis, dyskinesia, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, nervousness, dizziness, headache, excessive non-stop crying, and anxiety.[33][34] Some have argued that additional somatic and psychiatric symptoms associated with dopaminergic super-sensitivity, including dyskinesia and acute psychosis, are common features of withdrawal in individuals treated with neuroleptics.[35][36][37][38] This has led some to suggest that the withdrawal process might itself be schizo-mimetic, producing schizophrenia-like symptoms even in previously healthy patients, indicating a possible pharmacological origin of mental illness in a yet unknown percentage of patients currently and previously treated with antipsychotics. This question is unresolved, and remains a highly controversial issue among professionals in the medical and mental health communities, as well the public.[39] Complicated and long-lasting rebound insomnia symptoms can also occur after withdrawing from antipsychotics.[citation needed]

[edit] Overdosage

Children or adults who ingested acute overdoses have usually manifested central nervous system depression ranging from mild sedation to coma; serum concentrations of aripiprazole and dehydroaripiprazole in these patients were elevated by up to 3-4 fold over normal therapeutic levels, yet to date no deaths have been recorded.[40]

[edit] Drug interactions

Aripiprazole is a substrate of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Coadministration with medications that inhibit (e.g. paroxetine, fluoxetine) or induce (e.g. carbamazepine) these metabolic enzymes are known to increase and decrease, respectively, plasma levels of aripiprazole.[41] As such, anyone taking aripiprazole should be aware that their dosage of aripiprazole may need to be decreased.

Aripiprazole may change the subjective effects of alcohol. One study[42] found that aripiprazole increased the sedative effect and reduced the sense of euphoria normally associated with alcohol consumption. However, another alcohol study[43] found that there was no difference in subjective effect between a placebo group and a group taking aripiprazole.

[edit] Pharmacology

[edit] Binding profile

Aripiprazole acts as an antagonist/inverse agonist (unless otherwise noted) of the following receptors and transporters: [44]

|

Aripiprazole's mechanism of action is different from those of the other FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone). Rather than antagonizing the D2 receptor, aripiprazole acts as a D2 partial agonist.[45][46] Aripiprazole is also a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor, and like the other atypical antipsychotics displays an antagonist profile at the 5-HT2A receptor.[47][48] It also antagonizes the 5-HT7 receptor and acts as a partial agonist at the 5-HT2C receptor, both with high affinity. The latter action may underlie the minimal weight gain seen in the course of therapy.[49] Aripiprazole has moderate affinity for histamine, α-adrenergic, and D4 receptors as well as the serotonin transporter, while it has no appreciable affinity for cholinergic muscarinic receptors.[44]

D2 and D3 receptor occupancy levels are high, with average levels ranging between ~71% at 2 mg/day to ~96% at 40 mg/day.[50][51] Most atypical antipsychotics bind preferentially to extrastriatal receptors, but aripiprazole appears to be less preferential in this regard, as binding rates are high throughout the brain.[52]

Recently, it has been demonstrated that in 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice, aripiprazole does not reduce immobility time in the forced swim test (FST), and actually increases it.[53][54] This implicates 5-HT7 antagonism as playing a major role in aripiprazole's antidepressant effects, similarly to amisulpride.[53][54][55] Note, however, humans possess a splice variant not found in lower mammals (the "d" isoform), while mice possess one not found in humans (the "c"). The significantly altered c-terminus observed in 5-HT7(d) results in a similar binding affinity to the other forms of this receptor, however, the "c" variant found in lower mammals differs in affinity. This difference in expression means the receptor's function in modulating thalamic and hypothalamic output, and corresponding effect on fatigue perception and alertness may not be homologous in mice and humans.

Aripiprazole produces 2,3-dichlorophenylpiperazine (DCPP) as a metabolite similarly to how trazodone and nefazodone reduce to 3-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) and niaprazine converts to 4-fluorophenylpiperazine (pFPP).[56] It is unknown whether DCPP contributes to aripiprazole's pharmacology.[citation needed]

[edit] Pharmacokinetics

Aripiprazole displays linear kinetics and has an elimination half-life of approximately 75 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations are achieved in about 14 days. Cmax (maximum plasma concentration) is achieved 3–5 hours after oral dosing. Bioavailability of the oral tablets is about 90% and the drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolization (dehydrogenation, hydroxylation, and N-dealkylation), principally by the enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Its only known active metabolite is dehydro-aripiprazole, which typically accumulates to approximately 40% of the aripiprazole concentration. The parenteral drug is excreted only in traces, and its metabolites, active or not, are excreted via feces and urine.[44] When dosed daily, brain concentrations of aripiprazole will increase for a period of 10–14 days, before reaching stable constant levels.[citation needed]

[edit] Patent status

Otsuka's US patent on aripiprazole expires on October 20, 2014;[57] however, due to a pediatric extension, a generic will not become available until at least April 20, 2015.[8] Barr Laboratories (now Teva Pharmaceuticals) initiated a patent challenge under the Hatch-Waxman Act in March 2007.[58] On November 15, 2010, this challenge was rejected by a United States district court in New Jersey.[1][2]

[edit] Dosage forms

- Intramuscular injection, solution: 9.75 mg/mL (1.3 mL)

- Solution, oral: 1 mg/mL (150 mL) [contains propylene glycol, sucrose 400 mg/mL, and fructose 200 mg/mL; orange cream flavor]

- Tablet: 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg

- Tablet, orally disintegrating: 10 mg [contains phenylalanine 1.12 mg; creme de vanilla flavor]; 15 mg [contains phenylalanine 1.68 mg; creme de vanilla flavor]

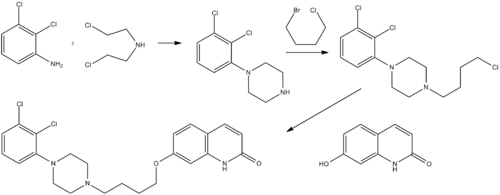

[edit] Synthesis

Aripiprazole can be synthesized beginning with a dichloroaniline and bis(2-chloroethyl)amine:[59]

[edit] References

- ^ Hitti, Miranda (20 November 2007). "FDA OKs Abilify for Depression". WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Keating, Gina (23 November 2009). "FDA OKs Abilify for child autism irritability". Reuters. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "abilify". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Abilify Receives Approval for Expanded Use in Children, Teens". Psych Central. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "Abilify Gets FDA Approval For Autism Irritability". Furious Seasons. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "FDA OKs Abilify for Depression : Antipsychotic Drug Approved for Use in Addition to Antidepressants for Treating Depression". WebMD. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ "Bristol-Myers Squibb to Pay More Than $515 Million to Resolve Allegations of Illegal Drug Marketing and Pricing". US Department of Justice. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ a b "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results". Electronic Orange Book. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Keck PE, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A, Ingenito G (September 2003). "A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania". Am J Psychiatry 160 (9): 1651–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1651. PMID 12944341.

- ^ Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Impellizzeri C, Kaplita S, Rollin L, Iwamoto T (July 2006). "Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 20 (4): 536–46. doi:10.1177/0269881106059693. PMID 16401666.

- ^ Vieta E, T'joen C, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Marcus RN, Sanchez R, Owen R, Nameche L (October 2008). "Efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole to either valproate or lithium in bipolar mania patients partially nonresponsive to valproate/lithium monotherapy: a placebo-controlled study". Am J Psychiatry 165 (10): 1316–25. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101560. PMID 18381903.

- ^ Keck PE, Orsulak PJ, Cutler AJ, Sanchez R, Torbeyns A, Marcus RN, McQuade RD, Carson WH (January 2009). "Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and lithium-controlled study". J Affect Disord 112 (1–3): 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.014. PMID 18835043.

- ^ Keck PE, Calabrese JR, McIntyre RS, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Eudicone JM, Carlson BX, Marcus RN, Sanchez R (October 2007). "Aripiprazole monotherapy for maintenance therapy in bipolar I disorder: a 100-week, double-blind study versus placebo". J Clin Psychiatry 68 (10): 1480–91. PMID 17960961.

- ^ Keck PE, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R (April 2006). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder". J Clin Psychiatry 67 (4): 626–37. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0414. PMID 16669728.

- ^ Young AH, Oren DA, Lowy A, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Carson WH, Spiller NH, Torbeyns AF, Sanchez R (January 2009). "Aripiprazole monotherapy in acute mania: 12-week randomised placebo- and haloperidol-controlled study". Br J Psychiatry 194 (1): 40–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.049965. PMID 19118324.

- ^ Vieta E, Bourin M, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Swanink R, Iwamoto T (September 2005). "Effectiveness of aripiprazole v. haloperidol in acute bipolar mania: double-blind, randomised, comparative 12-week trial". Br J Psychiatry 187 (3): 235–42. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.3.235. PMID 16135860.

- ^ Mazza M, Squillacioti MR, Pecora RD, Janiri L, Bria P (December 2008). "Beneficial acute antidepressant effects of aripiprazole as an adjunctive treatment or monotherapy in bipolar patients unresponsive to mood stabilizers: results from a 16-week open-label trial". Expert Opin Pharmacother 9 (18): 3145–9. doi:10.1517/14656560802504490. PMID 19040335.

- ^ Dunn RT, Stan VA, Chriki LS, Filkowski MM, Ghaemi SN (September 2008). "A prospective, open-label study of Aripiprazole mono- and adjunctive treatment in acute bipolar depression". J Affect Disord 110 (1–2): 70–4. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.01.004. PMID 18272230.

- ^ Mazza M, Squillacioti MR, Pecora RD, Janiri L, Bria P (January 2009). "Effect of aripiprazole on self-reported anhedonia in bipolar depressed patients". Psychiatry Res 165 (1–2): 193–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.003. PMID 18973955.

- ^ Thase ME, Jonas A, Khan A, Bowden CL, Wu X, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Marcus RN, Owen R (February 2008). "Aripiprazole monotherapy in nonpsychotic bipolar I depression: results of 2 randomized, placebo-controlled studies". J Clin Psychopharmacol 28 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181618eb4. PMID 18204335.

- ^ Muzina DJ, Momah C, Eudicone JM, Pikalov A, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, Sanchez R, Carlson BX (May 2008). "Aripiprazole monotherapy in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar I disorder: an analysis from a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 62 (5): 679–87. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01735.x. PMC 2324208. PMID 18373615.

- ^ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021436s21,021713s16,021729s8,021866s8lbl.pdf Section 2.3 pp 7-8

- ^ Yael Waknine (24 November 2009). "FDA Approves Aripiprazole to Treat Irritability in Autistic Children". Medscape Today. WebMD. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ 'Aripiprazole Blocks Reinstatement of Cocaine Seeking in an Animal Model of Relapse' Biological Psychiatry. Volume 61, Issue 5, Pages 582-590 (1 March 2007) http://www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/S0006-3223%2806%2900484-7/abstract

- ^ 'Addiction Medicine:Science and Practice. Author: Bankole A. Johnson. url=http://books.google.com.br/books?id=zvbr4Zn9S9MC&pg=PA145&lpg=PA145&dq=dissulfiram+stop+craving+for+amphetamines&source=bl&ots=PkBZ_o4vXK&sig=J22yh5pVYFggqKMRaiJE0Ejmmgg&hl=pt-BR&ei=7v-xToz9LsLFgAeM3r2kAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ "ABILIFY (aripiprazole) [package insert].". Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "ABILIFY (aripiprazole) [package insert].". Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Abbasian C, Power P (March 2009). "A case of aripiprazole and tardive dyskinesia". J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 23 (2): 214–5. doi:10.1177/0269881108089591. PMID 18515468.

- ^ Zaidi SH, Faruqui RA (January 2008). "Aripiprazole is associated with early onset of Tardive Dyskinesia like presentation in a patient with ABI and psychosis". Brain Inj 22 (1): 99–102. doi:10.1080/02699050701822493. PMID 18183513.

- ^ Maytal G, Ostacher M, Stern TA (June 2006). "Aripiprazole-related tardive dyskinesia". CNS Spectr 11 (6): 435–9. PMID 16816781.

- ^ http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/pdfviewer.aspx?isAttachment=true&documentid=16161

- ^ Group, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 0260-535X Check

|isbn=value (help). "Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse." - ^ Kim, DR.; Staab, JP. (May 2005). "Quetiapine discontinuation syndrome". Am J Psychiatry 162 (5): 1020. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1020. PMID 15863814.

- ^ Michaelides, C.; Thakore-James, M.; Durso, R. (Jun 2005). "Reversible withdrawal dyskinesia associated with quetiapine". Mov Disord 20 (6): 769–70. doi:10.1002/mds.20427. PMID 15747370.

- ^ Chouinard, G.; Jones, BD. (Jan 1980). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis: clinical and pharmacologic characteristics". Am J Psychiatry 137 (1): 16–21. PMID 6101522.

- ^ Miller, R.; Chouinard, G. (Nov 1993). "Loss of striatal cholinergic neurons as a basis for tardive and L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis and refractory schizophrenia". Biol Psychiatry 34 (10): 713–38. PMID 7904833.

- ^ Chouinard, G.; Jones, BD.; Annable, L. (Nov 1978). "Neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis". Am J Psychiatry 135 (11): 1409–10. PMID 30291.

- ^ Seeman, P.; Weinshenker, D.; Quiron, R.; Srivastava, LK.; Bhardwaj, SK.; Grandy, DK.; Premont, RT.; Sotnikova, TD.; Boksa, P.; El-Ghundi, M.; O'dowd, BF.; George, SR.; Perreault, ML.; Mannisto, PT; Robinson, S.; Palmiter, RD.; Tallerico, T. (Mar 2005). "Dopamine supersensitivity correlates with D2High states, implying many paths to psychosis". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (9): 3513–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409766102. PMC 548961. PMID 15716360.

- ^ Moncrieff, J. (Jul 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatr Scand 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 105-106.

- ^ "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Warnings and Precautions". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Kranzler, Henry R. et al. (2008). "Effects of Aripiprazole on Subjective and Physiological Responses to Alcohol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 32 (4): 573–579. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00608.x. PMC 3159685. PMID 18261195.

- ^ Konstantin Voronin, Patrick Randall, Hugh Myrick, Raymond Anton (2008). "ARIPIPRAZOLE EFFECTS ON ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION AND SUBJECTIVE REPORTS IN A CLINICAL LABORATORY PARADIGM: POSSIBLE INFLUENCE OF SELF-CONTROL". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 32 (11): 1954–1961. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00783.x. PMC 2588475. PMID 18782344.

- ^ a b c "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Clinical Pharmacology". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Lawler CP et al. (1999). "Interactions of the novel antipsychotic aripiprazole (OPC-14597) with dopamine and serotonin receptor subtypes". Neuropsychopharmacology 20 (6): 612–27. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00099-2. PMID 10327430.

- ^ Burstein ES, Ma J, Wong S, Gao Y, Pham E, Knapp AE, Nash NR, Olsson R, Davis RE, Hacksell U, Weiner DM, Brann MR (December 2005). "Intrinsic Efficacy of Antipsychotics at Human D2, D3, and D4 Dopamine Receptors: Identification of the Clozapine Metabolite N-Desmethylclozapine as a D2/D3 Partial Agonist". J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315 (3): 1278–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.092155. PMID 16135699.

- ^ Jordan, S et al. (2002). "The antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor". Eur J Pharmacol 441 (3): 137–140. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01532-7. PMID 12063084.

- ^ Shapiro, DA et al. (2003). "Aripiprazole, A Novel Atypical Antipsychotic Drug with a Unique and Robust Pharmacology". Neuropsychopharmacology 28 (8): 1400–1411. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. PMID 12784105.

- ^ Zhang JY, Kowal DM, Nawoschik SP, Lou Z, Dunlop J (February 2006). "Distinct functional profiles of aripiprazole and olanzapine at RNA edited human 5-HT2C receptor isoforms". Biochem Pharmacol 71 (4): 521–9. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.007. PMID 16336943.

- ^ Kegeles, LS et al. (2008). "Dose–Occupancy Study of Striatal and Extrastriatal Dopamine D2 Receptors by Aripiprazole in Schizophrenia with PET and [18F]Fallypride". Neuropsychopharmacology 33 (13): 3111–3125. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.33. PMID 18418366.

- ^ Yokoi F, Gründer G, Biziere K, Stephane M, Dogan AS, Dannals RF, Ravert H, Suri A, Bramer S, Wong DF (August 2002). "Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride". Neuropsychopharmacology 27 (2): 248–59. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00304-4. PMID 12093598.

- ^ "In This Issue". Am J Psychiatry 165 (8): A46. August 2008. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.165.8.A46.

- ^ a b Hedlund PB (October 2009). "The 5-HT7 receptor and disorders of the nervous system: an overview". Psychopharmacology 206 (3): 345–54. doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1626-0. PMC 2841472. PMID 19649616.

- ^ a b Sarkisyan G, Roberts AJ, Hedlund PB (January 2010). "The 5-HT7 receptor as a mediator and modulator of antidepressant-like behavior". Behavioural Brain Research 209 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.022. PMC 2832919. PMID 20097233.

- ^ Abbas AI, Hedlund PB, Huang XP, Tran TB, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (July 2009). "Amisulpride is a potent 5-HT7 antagonist: relevance for antidepressant actions in vivo". Psychopharmacology 205 (1): 119–28. doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1521-8. PMC 2821721. PMID 19337725.

- ^ Caccia S (August 2007). "N-dealkylation of arylpiperazine derivatives: disposition and metabolism of the 1-aryl-piperazines formed". Current Drug Metabolism 8 (6): 612–22. doi:10.2174/138920007781368908. PMID 17691920.

- ^ Carbostyril derivatives (published October 20, 1989). April 9, 1991 Unknown parameter

|inventor1-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor1-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor2-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|patent-number=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor2-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor3-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor3-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|country-code=ignored (help) - ^ "Barr Confirms Filing an Application with a Paragraph IV Certification for ABILIFY(R) Tablets" (Press release). Barr Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2007-03-20. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ U.S. Patent 5,006,528

Aripiprazole-induced oculogyric crisis (acute dystonia).Jyotik T Bhachech.Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. Jul-Sept 2012,3:279-81.http://www.jpharmacol.com/article.asp?issn=0976-500X;year=2012;volume=3;issue=3;spage=279;epage=281;aulast=Bhachech;type=0

[edit] External links

- Abilify website

- Abilify Full Prescribing Information (for Health Care Professionals)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Aripiprazole

- Abilify adverse events reported to the FDA

- Mechanism of Action Of Aripiprazole

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||