by Henry on April 25, 2013

I have a gloomy article on the parlous state of social democracy in Italy and elsewhere in Europe up at Aeon. The draft was completed two weeks ago; if anything the events in the interim have given even more cause for depression. The Italian Democratic Party looks on the verge of entering into a coalition with Berlusconi’s people that is neither appetizing nor particularly convincing – it has also led to a very bad three way split between (1) the party’s old guard, (2) a quasi-Blairite wing lead by Matteo Renzi, the mayor of Florence and (3) the left (who would have liked to see Renzi win, if only because whoever ends up as prime minister under current circumstances is likely to be badly damaged). The Movimento 5 Stelle is still dithering, while trying to attract defectors from the Democratic Party’s left (a few weeks ago, the Democratic Party hoped that all the movement would be in the other direction). It has done poorly in a recent regional election, and is likely less enthusiastic about immediate elections than it was a few days ago. Even by the impressive standards of its international peers, the Italian left and center left have a prodigious capacity for screwing stuff up due to factionalism. It would be fair to say that it’s not withering away through disuse.

Last September, Il Partito Democratico, the Italian Democratic Party, asked me to talk about politics and the internet at its summer school in Cortona. Political summer schools are usually pleasant — Cortona is a medieval Tuscan hill town with excellent restaurants — and unexciting. Academics and public intellectuals give talks organised loosely around a theme; in this case, the challenges of ‘communication and democracy’. Young party activists politely listen to our speeches while they wait to do the real business of politics, between sessions and at the evening meals.

by John Holbo on April 24, 2013

Remember a couple years back? I made some sort of a kind of a graphical fiction, Squid & Owl?

I made it into a book. Mom liked it a lot! A few other people did, too. Fast forward a couple years: Comixology comes along, and it’s a great platform for digital comics. And, finally, they started allowing independent submissions. And, long story short, they accepted Squid & Owl and now it’s sitting proudly in the Staff Picks section. Only 99 cents! 106 pages. Such a bargain! You should buy it. You should give it a lot of stars. Help me achieve the fame I so richly deserve.

(Speaking of which: it’s getting harder and harder to impress my 11-year old daughter, but this time I did it. Because Atomic Robo is on Comixology, and she really, really likes Atomic Robo. So I must be cool.)

by niamh on April 24, 2013

Greece is at the hard end of another European policy problem, related to austerity, but this time to do with immigration, and it’s turning into a serious human rights and humanitarian crisis. According to Europe’s border control agency Frontex, 93% of migrants to Europe came through eastern and central Mediterranean routes in 2011.With the tightening of the patrolling of Spanish and Italian access routes, most of these arrived first in Greece, with legal rights under the European Convention of Human Rights to seek asylum status there. Greece doesn’t have the resources to provide adequate social services, and the justice system is grossly inadequate to deal with the demands put on it. This means that large numbers of people are cast adrift in Greece in a legal limbo and with no resources. They are then at the mercy not only of highly repressive policing but of the fascist organization Golden Dawn, whose growing influence is now also starting to contaminate the political discourse of other political parties. A new internet crowd-released film, Into the Fire, documents the human face on what’s going on.

This is not just a story about Greece, but about European policy more generally. Under what is known as the Dublin regulation, people can only claim asylum in the EU country in which they first arrive. It means that if anyone manages to move on to another country, their claim to asylum need not be heard in that country, but they can be summarily deported back to the country in which they first arrived. This was supposed to be a burden-sharing measure to cut out parallel asylum claims in multiple jurisdictions. But in effect, because of the way people arrive in Europe, it corrals the EU’s asylum-seekers into the southern European countries, and increasingly concentrates it in Greece. A 2011 decision by the European Court of Human Rights found that, unlike other EU member states, Greece was not able to vindicate people’s rights under the European Convention on Human Rights, and that deportations back there are not defensible. But as shown in the documentary Dublin’s Trap: another side of the Greek crisis, these rights are hard to access and the implications extend to very few people. And securing ’Fortress Europe’ is taking an even greater toll on human lives:

…at least 18,567 people have died since 1988 along the european borders. Among them 8,695 were reported to be missing in the sea. The majority of them, 13,733 people, lost their life trying to cross the Mediterranean sea and the Atlantic Ocean towards Europe. And 2011 was the worst year ever, considering that during the year at least 2,352 people have died at the gates of Europe.

There are lots of questions about other European countries’ ways of dealing with asylum seekers and refugees. Ireland’s citizenship laws were changed in 2004 to deter possible claimants; people are left for

unconscionably long periods living in

‘direct provision’ accommodation; and the rate of successful application is

very low indeed. But the scale of the humanitarian and human rights issues building up in Greece is something else again. And while many northern European policy-makers may well be silently grateful that the issue of rising refugee pressures (most recently from Syria) is kept out of their country, the

fillip it gives to Golden Dawn, the third-largest political grouping in Greece in recent polls, should be a cause for deep alarm right across Europe.

by John Quiggin on April 24, 2013

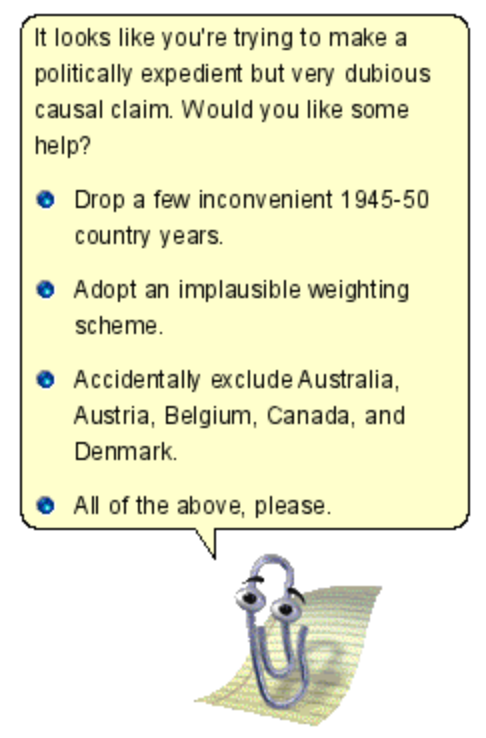

With the exception of an unnameable region bordering on the Eastern Mediterranean, posts on diet and exercise seem to promote more bitter disputes than any others. So, in the spirit of adventure, I’m going to step away from my usual program of soft and fluffy topics like the bubbliness of bitcoins, the uselessness of navies and the agnotology of climate denial, and tackle the thorny question of running vs walking.

Happily, and unlike, say climate science, this is a question on which you can find a reputable scientific study to support just about any position you care to name, and even some that appear to support both sides, so I’m just going to pick the ones I like, draw the conclusions I want, and invite you all to have it out in the comments thread. I’m also going to attempt the classic move of representing the opposing positions as extremes, relative to which I occupy the sensible centre.

[click to continue…]

by John Holbo on April 23, 2013

A couple weeks back the Mercatus Freedom In The 50 States Index came out and there was much bemusement to be had by most. Matthew Yglesias may be wrong on dragons but he was right, I think, that the exercise holds promise chiefly as a solution to a coalition-building problem: how to “simultaneously preserve libertarianism as a distinct brand and also preserve libertarianism’s strong alliance with social conservatism.” Regular old freedom-loving folk, by contrast, will tend to be left cold.

I thought I would add a footnote to this, and give the CT commentariat an opportunity to weigh in. It might seem that the footnote to add is one of the woolly ones, from Isaiah Berlin’s “Two Concepts of Liberty”: [click to continue…]

by Henry on April 22, 2013

I hate to say it, but Matt Yglesias has just gone too far this time. If you want to apply simplistic economic arguments to complex social situations, you can’t just wave your hands and suggest that the market for dragons in Westeros and neighboring lands is riddled with Akerlof style information asymmetries and complementarity problems. Instead, you should be waving your hands and arguing that under reasonable assumptions, there isn’t a market for dragons in the first place. The problem isn’t an Akerlof-style one, where there are unobservable variations in quality between dragons. The actual qualities of dragons for plunder and conquest appear to be highly visible – the bigger your dragon, the better they are at toasting enemy armies (the slavers in the TV series know this, and go for the largest of the litter). The problem is that the actual good being bought and sold is not the dragon-as-a-physical-entity, but the loyalty of the dragon-as-a-physical-entity. And this simply isn’t a salable commodity, as best as we can tell from George R.R. Martin’s books and the television series. Daenerys can’t sell a set of affections which appear to be rooted in a quasi-maternal bond, based on the Targareyn bloodline, or some combination of the two. Dragons don’t seem to vary in this quality.

Furthermore, even if George R.R. Martin’s world was one in which Daenerys were somehow able to transfer the loyalties and affections of a dragon to another, this problem would still be insuperable, because dragons are so powerful. The buyer of the dragon’s loyalty could never be sure that Daenerys had actually ‘sold’ it, because loyalty is unobservable. Perhaps Daenerys and the dragon were simply waiting for the right moment to turn on them. And since dragons mature, and fully grown dragons can more or less do whatever the hell they want, Daenerys and the dragon are essentially too powerful (PDF) to make bargains that they have a long term incentive to keep. This is a classic form of Thomas Schelling’s credible commitment problem – Schelling remarks in The Strategy of Conflict that the right to be sued is very valuable, because it allows one to make credible commitments. Daenerys, with her dragons, is too powerful over the longer term to be able to make credible commitments.

Hence, the sale of the Unsullied could never occur in equilibrium. The slavers are offering a military asset whose loyalty is unimpeachably transferrable – once the Unsullied have a new master, they obey that master unquestioningly. This is why they are supposed to be so valuable (lots of dubious implications in there of course …). Daenerys is offering a military asset whose loyalty is at best unobservable. Therefore, it can’t be readily sold or exchanged. The exchange should never happen.

by Henry on April 22, 2013

It’s now been exactly a decade since Charles Krauthammer told us that

Hans Blix had five months to find weapons. He found nothing. We’ve had five weeks. Come back to me in five months. If we haven’t found any, we will have a credibility problem.

Charles Krauthammer has not only had that five month period, but twenty-three other five month periods after that first one, for weapons of mass destruction to be found. It’s news to no-one that no weapons have been found. It’s news to no-one that the reason they haven’t been found is because they weren’t there in the first place. It’s news to no-one that Charles Krauthammer is still a columnist at the Washington Post, a syndicated columnist across the US, and a regular talking head on TV. It’s news to no-one that Fred Hiatt, his then-boss and fellow Iraq bullshit artist is still the editor of the Washington Post’s editorial page. Or that Jackson Diehl, who I heard at the time from Washington Post people was even worse than Hiatt, is still there too.

In short, it’s news to no-one that Iraq War related “credibility problems” aren’t really so much of a problem if you’re Charles Krauthammer. Or Fred Hiatt. Or any of the multitudes of journalists or pundits who flagrantly pimped for this disastrous war and hasn’t even gestured towards publicly admitting that they committed a gross dereliction of duty. I think it’s worth remembering Krauthammer day on this blog as long as Krauthammer and the people around him continue to pollute public discourse. I can’t imagine that it’s particularly efficacious, but the alternative of succumbing to the general amnesia seems even less attractive.

by Corey Robin on April 21, 2013

I love Benno Schmidt. He’s the chair of the Board of Trustees of CUNY, where I teach, and a former president of Yale. More important, he’s a man who’s spent so much time in the business world that he’s no longer capable of leaving anything to the imagination. So you get from him a refreshingly crude form of honesty that you ordinarily don’t find in academia. Certainly not in university leaders, who are so adept at making themselves misunderstood that you’d think they were trained by apparatchiks in the former Soviet Union. Or Straussians.

Anyway, Benno was interviewed by the New York Post about his plans for CUNY Chancellor Matthew Goldstein, who’ll be retiring at the end of the year. Long story short: Schmidt wants to make things nice for Goldstein. Even though CUNY’s faculty are badly paid, even though most of the teaching is done by adjuncts who are really badly paid—like, horribly paid (they’re treated even worse)—Benno’s got his eyes on the prize: making sure Matt has a nice sendoff and a sweet retirement.

Our union at Brooklyn College has a blog, which you should be checking out regularly, and they reproduced the Post article. Here are some highlights: [click to continue…]

by Eric on April 18, 2013

When a book reviewer or manuscript referee describes an argument as “persuasive” or “convincing” without explaining exactly what it is that has persuaded or convinced, or alternatively what it would take to persuade or convince, I feel I’ve failed to get my money’s worth. I suspect I’m getting a purely subjective assessment dressed up in fancy language, and I’ve long had a hunch it’s been increasing in use, at least in my discipline.1

But inasmuch as I had only a hunch that irritatingly subjective language was increasingly used, I knew I was being terribly inconsistent, which troubled me. So at last I went to the data.

I searched JSTOR for instances of “persuasive” and “convincing” and their opposites by year in reviews published in the American Historical Review between 1958 and 2007. To weight the occurrences, I also searched AHR reviews by year for instances of the word “that,” reckoning this was a pretty neutral word to look for. I divided the former by the latter to get a sense of the frequency of subjective language in AHR book reviews. Below is the result, which I hope is more persuasive than my hunch.

The language of “persuasive” is on the increase. Unless I’ve made an Excel error.

1I also have a terrible prescriptivist annoyance over “persuaded … that” and “convinced … of” but we won’t get into it.

by Maria on April 18, 2013

I’ve recently moved from Edinburgh to Bournemouth for a couple of months.Bournemouth is a bit tattier than I’d expected. I reckon 25% of the shop fronts nearby are vacant and the three hair salons I walk past each morning never seem to have more than one customer at a time. But the summer crowds aren’t yet here, and we have the gloriously long beach front to run and cycle along. And there’s always the breath-takingly odd New Forest national park just down the road. It’s like taking a trip back to childhood to round a New Forest corner at fifteen miles an hour and come face to face with a winter-coated donkey. Make the mistake of stopping the car and he’ll edge cheekily up to the window, baring his teeth to beg a free snack.

Bournemouth has a great system of public gyms, and as I’m on a short hiatus from paid employment (using the unexpected gift of 12 free weeks to write) I’ve discovered the wonder of daytime exercise classes. There is something utterly joyous about being at least ten years below the median age of a spinning session, and constantly dialing the bike down to keep up.

But being out of the army-wife bubble is hard. I won’t be going to two or three coffee mornings, then hosting my own and, hey presto, have met most of my local friends already. Last week, the only in-person conversation I had that wasn’t ‘here’s your change’ and ‘thanks very much’ was a rapidly-spinning-into-enthusiastically-shared-interests chat about steampunk with a guy in the Espresso Kitchen café. (I was re-reading Felix Gilman’s The Rise of Ransom City, and scribbling notes for the upcoming CT seminar on same.) Espresso Guy and I got to wondering if there are other kindred spirits about, and whether they might like to meet up for some rather excellent coffee in The Triangle in Bournemouth.

So, are there any CT readers on the south coast who would like to meet up at Espresso Kitchen at some point over the next week or so? Purely social agenda in mind, for chats about politics, books, and how nice it is that the People’s Republic of Tory have finally stopped broadcasting Thatcherite hagiography eight hours a day. The café can open late or serve food, and they’re open to hosting readings, book clubs, or just a few like-minded souls having a natter.

by Harry on April 18, 2013

The Boston Review symposium I pointed to last year on James Heckman’s “Promoting Social Mobility” is now out in book form as Giving Kids a Fair Chance . Its all still on the web, at least right now, but the book is cute and inexpensive. I’m curious what other people’s experience is, but I find that when I assign a book in class it gets read by more students, and more carefully, than if I assign something from the web; so I am planning to use it alongside Unequal Childhoods

. Its all still on the web, at least right now, but the book is cute and inexpensive. I’m curious what other people’s experience is, but I find that when I assign a book in class it gets read by more students, and more carefully, than if I assign something from the web; so I am planning to use it alongside Unequal Childhoods with my freshman class in the fall.

with my freshman class in the fall.

by Harry on April 18, 2013

There’s a very good piece by Jal Mehta in the Times last Sunday, reflecting on A Nation at Risk. He criticizes not teachers, but the profession of teaching:

Teaching requires a professional model, like we have in medicine, law, engineering, accounting, architecture and many other fields. In these professions, consistency of quality is created less by holding individual practitioners accountable and more by building a body of knowledge, carefully training people in that knowledge, requiring them to show expertise before they become licensed, and then using their professions’ standards to guide their work.

By these criteria, American education is a failed profession. There is no widely agreed-upon knowledge base, training is brief or nonexistent, the criteria for passing licensing exams are much lower than in other fields, and there is little continuous professional guidance. It is not surprising, then, that researchers find wide variation in teaching skills across classrooms; in the absence of a system devoted to developing consistent expertise, we have teachers essentially winging it as they go along, with predictably uneven results.

I’m very uneasy with his subsequent comparisons with countries that do better, though—Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Finland, Canada—which lack large swathes of relative poverty and, in a couple of cases authoritarian cultures. Its not as though these countries have developed technologies for teaching the kinds of student that American schools educate. But he makes an interesting point about why we know so little, and so little of what we do know is usable:

Anthony S. Bryk, president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, has estimated that other fields spend 5 percent to 15 percent of their budgets on research and development, while in education, it is around 0.25 percent. Education-school researchers publish for fellow academics; teachers develop practical knowledge but do not evaluate or share it; commercial curriculum designers make what districts and states will buy, with little regard for quality.

Anyway, there’s lots of good stuff, so read the whole thing.

by John Quiggin on April 17, 2013

Over at the National Interest, I have a piece arguing that Bitcoin is a more perfect example of a bubble, and therefore a more perfect refutation of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, than anything seen previously. Key quote

It beats the classic historical example, produced during the 18th century South Sea Bubble of “a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” After all, the promoter of this enterprise might, in principle, have had a genuine secret plan. Bitcoin also outmatches Ponzi schemes, which rely on the claim that the issuer is undertaking some kind of financial arbitrage (the original Ponzi scheme was supposed to involve postal orders). The closest parallel is the fictitious dotcom company imagined in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, whose only product was its own stock.

by Eric on April 17, 2013

Today Jim Rickards (author of Currency Wars) says,

Last week I had x ounces of #Gold. Today I have x ounces. So value is unchanged. Constant at x ounces. Dollar is volatile though. #ThinkOz

I know it’s a failing in me, but it is hard not to ponder whether this is charlatanism or delusion. As John Maynard Keynes says in the first sentence of his Tract on Monetary Reform, “Money is only important for what it will procure.” With the stubborn volatility of the dollar, Rickards’s ounces procure rather less than they recently did.

The exhortation #ThinkOz is of course wonderful. I think now of hashtags past…

Last week I had x bulbs of #Tulips. Today I have x bulbs. So value is unchanged. Constant at x bulbs. Florin is volatile though. #ThinkBulbs

Money is a medium of exchange and a store of value, they say.