Momentum

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Common symbol(s): | p |

| SI unit: | kg m/s or N s |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Core topics

|

In classical mechanics, linear momentum or translational momentum (pl. momenta; SI unit kg m/s, or equivalently, N s) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. For example, a heavy truck moving fast has a large momentum—it takes a large and prolonged force to get the truck up to this speed, and it takes a large and prolonged force to bring it to a stop afterwards. If the truck were lighter, or moving more slowly, then it would have less momentum.

Like velocity, linear momentum is a vector quantity, possessing a direction as well as a magnitude:

Linear momentum is also a conserved quantity, meaning that if a closed system is not affected by external forces, its total linear momentum cannot change. In classical mechanics, conservation of linear momentum is implied by Newton's laws; but it also holds in special relativity (with a modified formula) and, with appropriate definitions, a (generalized) linear momentum conservation law holds in electrodynamics, quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, and general relativity.

Contents |

Newtonian mechanics

Momentum has a direction as well as magnitude. Quantities that have both a magnitude and a direction are known as vector quantities. Because momentum has a direction, it can be used to predict the resulting direction of objects after they collide, as well as their speeds. Below, the basic properties of momentum are described in one dimension. The vector equations are almost identical to the scalar equations (see multiple dimensions).

Single particle

The momentum of a particle is traditionally represented by the letter p. It is the product of two quantities, the mass (represented by the letter m) and velocity (v):[1]

The units of momentum are the product of the units of mass and velocity. In SI units, if the mass is in kilograms and the velocity in meters per second, then the momentum is in kilograms meters/second (kg m/s). Being a vector, momentum has magnitude and direction. For example, a model airplane of 1 kg, traveling due north at 1 m/s in straight and level flight, has a momentum of 1 kg m/s due north measured from the ground.

Many particles

The momentum of a system of particles is the sum of their momenta. If two particles have masses m1 and m2, and velocities v1 and v2, the total momentum is

The momenta of more than two particles can be added in the same way.

A system of particles has a center of mass, a point determined by the weighted sum of their positions:

If all the particles are moving, the center of mass will generally be moving as well. If the center of mass is moving at velocity vcm, the momentum is:

This is known as Euler's first law.[2][3]

Relation to force

If a force F is applied to a particle for a time interval Δt, the momentum of the particle changes by an amount

In differential form, this gives Newton's second law: the rate of change of the momentum of a particle is equal to the force F acting on it:[1]

If the force depends on time, the change in momentum (or impulse) between times t1 and t2 is

The second law only applies to a particle that does not exchange matter with its surroundings,[4] and so it is equivalent to write

so the force is equal to mass times acceleration.[1]

Example: a model airplane of 1 kg accelerates from rest to a velocity of 6 m/s due north in 2 s. The thrust required to produce this acceleration is 3 newton. The change in momentum is 6 kg m/s. The rate of change of momentum is 3 (kg m/s)/s = 3 N.

Conservation

In a closed system (one that does not exchange any matter with the outside and is not acted on by outside forces) the total momentum is constant. This fact, known as the law of conservation of momentum, is implied by Newton's laws of motion.[5] Suppose, for example, that two particles interact. Because of the third law, the forces between them are equal and opposite. If the particles are numbered 1 and 2, the second law states that F1 = dp1/dt and F2 = dp2/dt. Therefore

or

If the velocities of the particles are u1 and u2 before the interaction, and afterwards they are v1 and v2, then

This law holds no matter how complicated the force is between particles. Similarly, if there are several particles, the momentum exchanged between each pair of particles adds up to zero, so the total change in momentum is zero. This conservation law applies to all interactions, including collisions and separations caused by explosive forces.[5] It can also be generalized to situations where Newton's laws do not hold, for example in the theory of relativity and in electrodynamics.[6]

Dependence on reference frame

Momentum is a measurable quantity, and the measurement depends on the motion of the observer. For example, if an apple is sitting in a glass elevator that is descending, an outside observer looking into the elevator sees the apple moving, so to that observer the apple has a nonzero momentum. To someone inside the elevator, the apple does not move, so it has zero momentum. The two observers each have a frame of reference in which they observe motions, and if the elevator is descending steadily they will see behavior that is consistent with the same physical laws.

Suppose a particle has position x in a stationary frame of reference. From the point of view of another frame of reference moving at a uniform speed u, the position (represented by a primed coordinate) changes with time as

This is called a Galilean transformation. If the particle is moving at speed dx/dt = v in the first frame of reference, in the second it is moving at speed

Since u does not change, the accelerations are the same:

Thus, momentum is conserved in both reference frames. Moreover, as long as the force has the same form in both frames, Newton's second law is unchanged. Forces such as Newtonian gravity, which depend only on the scalar distance between objects, satisfy this criterion. This independence of reference frame is called Newtonian relativity or Galilean invariance.[7]

A change of reference frame can often simplify calculations of motion. For example, in a collision of two particles a reference frame can be chosen where one particle begins at rest. Another commonly used reference frame is the center of mass frame, one that is moving with the center of mass. In this frame, the total momentum is zero.

Application to collisions

By itself, the law of conservation of momentum is not enough to determine the motion of particles after a collision. Another property of the motion, kinetic energy, must be known. This is not necessarily conserved. If it is conserved, the collision is called an elastic collision; if not, it is an inelastic collision.

Elastic collisions

An elastic collision is one in which no kinetic energy is lost. Perfectly elastic "collisions" can occur when the objects do not touch each other, as for example in atomic or nuclear scattering where electric repulsion keeps them apart. A slingshot maneuver of a satellite around a planet can also be viewed as a perfectly elastic collision from a distance. A collision between two pool balls is a good example of an almost totally elastic collision, due to their high rigidity; but when bodies come in contact there is always some dissipation.[8]

A head-on elastic collision between two bodies can be represented by velocities in one dimension, along a line passing through the bodies. If the velocities are u1 and u2 before the collision and v1 and v2 after, the equations expressing conservation of momentum and kinetic energy are:

A change of reference frame can often simplify the analysis of a collision. For example, suppose there are two bodies of equal mass m, one stationary and one approaching the other at a speed v (as in the figure). The center of mass is moving at speed v/2 and both bodies are moving towards it at speed v/2. Because of the symmetry, after the collision both must be moving away from the center of mass at the same speed. Adding the speed of the center of mass to both, we find that the body that was moving is now stopped and the other is moving away at speed v. The bodies have exchanged their velocities. Regardless of the velocities of the bodies, a switch to the center of mass frame leads us to the same conclusion. Therefore, the final velocities are given by[5]

In general, when the initial velocities are known, the final velocities are given by[9]

If one body has much greater mass than the other, its velocity will be little affected by a collision while the other body will experience a large change.

Inelastic collisions

In an inelastic collision, some of the kinetic energy of the colliding bodies is converted into other forms of energy such as heat or sound. Examples include traffic collisions,[10] in which the effect of lost kinetic energy can be seen in the damage to the vehicles; electrons losing some of their energy to atoms (as in the Franck–Hertz experiment);[11] and particle accelerators in which the kinetic energy is converted into mass in the form of new particles.

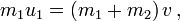

In a perfectly inelastic collision (such as a bug hitting a windshield), both bodies have the same motion afterwards. If one body is motionless to begin with, the equation for conservation of momentum is

so

In a frame of reference moving at the speed v), the objects are brought to rest by the collision and 100% of the kinetic energy is converted.

One measure of the inelasticity of the collision is the coefficient of restitution CR, defined as the ratio of relative velocity of separation to relative velocity of approach. In applying this measure to ball sports, this can be easily measured using the following formula:[12]

The momentum and energy equations also apply to the motions of objects that begin together and then move apart. For example, an explosion is the result of a chain reaction that transforms potential energy stored in chemical, mechanical, or nuclear form into kinetic energy, acoustic energy, and electromagnetic radiation. Rockets also make use of conservation of momentum: propellant is thrust outward, gaining momentum, and an equal and opposite momentum is imparted to the rocket.[13]

Multiple dimensions

Real motion has both direction and magnitude and must be represented by a vector. In a coordinate system with x, y, z axes, velocity has components vx in the x direction, vy in the y direction, vz in the z direction. The vector is represented by a boldface symbol:[14]

Similarly, the momentum is a vector quantity and is represented by a boldface symbol:

The equations in the previous sections work in vector form if the scalars p and v are replaced by vectors p and v. Each vector equation represents three scalar equations. For example,

represents three equations:[14]

The kinetic energy equations are exceptions to the above replacement rule. The equations are still one-dimensional, but each scalar represents the magnitude of the vector, for example,

Each vector equation represents three scalar equations. Often coordinates can be chosen so that only two components are needed, as in the figure. Each component can be obtained separately and the results combined to produce a vector result.[14]

A simple construction involving the center of mass frame can be used to show that if a stationary elastic sphere is struck by a moving sphere, the two will head off at right angles after the collision (as in the figure).[15]

Objects of variable mass

The concept of momentum plays a fundamental role in explaining the behavior of variable-mass objects such as a rocket ejecting fuel or a star accreting gas. In analyzing such an object, one treats the object's mass as a function that varies with time: m(t). The momentum of the object at time t is therefore p(t) = m(t)v(t). One might then try to invoke Newton's second law of motion by saying that the external force F on the object is related to its momentum p(t) by F = dp/dt, but this is incorrect, as is the related expression found by applying the product rule to d(mv)/dt:[16]

This equation does not correctly describe the motion of variable-mass objects. The correct equation is

where u is the velocity of the ejected/accreted mass as seen in the object's rest frame.[16] This is distinct from v, which is the velocity of the object itself as seen in an inertial frame.

This equation is derived by keeping track of both the momentum of the object as well as the momentum of the ejected/accreted mass. When considered together, the object and the mass constitute a closed system in which total momentum is conserved.

Generalized coordinates

Newton's laws can be difficult to apply to many kinds of motion because the motion is limited by constraints. For example, a bead on an abacus is constrained to move along its wire and a pendulum bob is constrained to swing at a fixed distance from the pivot. Many such constraints can be incorporated by changing the normal Cartesian coordinates to a set of generalized coordinates that may be fewer in number.[17] Refined mathematical methods have been developed for solving mechanics problems in generalized coordinates. They introduce a generalized momentum, also known as the canonical or conjugate momentum, that extends the concepts of both linear momentum and angular momentum. To distinguish it from generalized momentum, the product of mass and velocity is also referred to as mechanical, kinetic or kinematic momentum.[6][18][19] The two main methods are described below.

Lagrangian mechanics

In Lagrangian mechanics, a Lagrangian is defined as the difference between the kinetic energy T and the potential energy V:

If the generalized coordinates are represented as a vector q = (q1, q2, ... , qN) and time differentiation is represented by a dot over the variable, then the equations of motion (known as the Lagrange or Euler–Lagrange equations) are a set of N equations:[20]

If a coordinate qi is not a Cartesian coordinate, the associated generalized momentum component pi does not necessarily have the dimensions of linear momentum. Even if qi is a Cartesian coordinate, pi will not be the same as the mechanical momentum if the potential depends on velocity.[6] Some sources represent the kinematic momentum by the symbol Π.[21]

In this mathematical framework, a generalized momentum is associated with the generalized coordinates. Its components are defined as

Each component pj is said to be the conjugate momentum for the coordinate qj.

Now if a given coordinate qi does not appear in the Lagrangian (although its time derivative might appear), then

This is the generalization of the conservation of momentum.[6]

Even if the generalized coordinates are just the ordinary spatial coordinates, the conjugate momenta are not necessarily the ordinary momentum coordinates. An example is found in the section on electromagnetism.

Hamiltonian mechanics

In Hamiltonian mechanics, the Lagrangian (a function of generalized coordinates and their derivatives) is replaced by a Hamiltonian that is a function of generalized coordinates and momentum. The Hamiltonian is defined as

where the momentum is obtained by differentiating the Lagrangian as above. The Hamiltonian equations of motion are[22]

As in Lagrangian mechanics, if a generalized coordinate does not appear in the Hamiltonian, its conjugate momentum component is conserved.[23]

Symmetry and conservation

Conservation of momentum is a mathematical consequence of the homogeneity (shift symmetry) of space (position in space is the canonical conjugate quantity to momentum). That is, conservation of momentum is a consequence of the fact that the laws of physics do not depend on position; this is a special case of Noether's theorem.[24]

Relativistic mechanics

Lorentz invariance

Newtonian physics assumes that absolute time and space exist outside of any observer; this gives rise to the Galilean invariance described earlier. It also results in a prediction that the speed of light can vary from one reference frame to another. This is contrary to observation. In the special theory of relativity, Einstein keeps the postulate that the equations of motion do not depend on the reference frame, but assumes that the speed of light c is invariant. As a result, position and time in two reference frames are related by the Lorentz transformation instead of the Galilean transformation.[25]

Consider, for example, a reference frame moving relative to another at velocity v in the x direction. The Galilean transformation gives the coordinates of the moving frame as

while the Lorentz transformation gives[26]

where γ is the Lorentz factor:

Newton's second law, with mass fixed, is not invariant under a Lorentz transformation. However, it can be made invariant by making the inertial mass m of an object a function of velocity:

m0 is the object's invariant mass.[27]

The modified momentum,

obeys Newton's second law:

Within the domain of classical mechanics, relativistic momentum closely approximates Newtonian momentum: at low velocity, γm0v is approximately equal to m0v, the Newtonian expression for momentum.

Four-vector formulation

In the theory of relativity, physical quantities are expressed in terms of four-vectors that include time as a fourth coordinate along with the three space coordinates. These vectors are generally represented by capital letters, for example R for position. The expression for the four-momentum depends on how the coordinates are expressed. Time may be given in its normal units or multiplied by the speed of light so that all the components of the four-vector have dimensions of length. If the latter scaling is used, an interval of proper time, τ, defined by[28]

is invariant under Lorentz transformations (in this expression and in what follows the (+ − − −) metric signature has been used, different authors use different conventions). Mathematically this invariance can be ensured in one of two ways: by treating the four-vectors as Euclidean vectors and multiplying time by the square root of -1; or by keeping time a real quantity and embedding the vectors in a Minkowski space.[29] In a Minkowski space, the scalar product of two four-vectors U = (U0,U1,U2,U3) and V = (V0,V1,V2,V3) is defined as

In all the coordinate systems, the (contravariant) relativistic four-velocity is defined by

and the (contravariant) four-momentum is

where m0 is the invariant mass. If R = (ct,x,y,z) (in Minkowski space), then[note 1]

Using Einstein's mass-energy equivalence, E = mc2, this can be rewritten as

Thus, conservation of four-momentum is Lorentz-invariant and implies conservation of both mass and energy.

The magnitude of the momentum four-vector is equal to m0c:

and is invariant across all reference frames.

The relativistic energy–momentum relationship holds even for massless particles such as photons; by setting m0 = 0 it follows that

In a game of relativistic "billiards", if a stationary particle is hit by a moving particle in an elastic collision, the paths formed by the two afterwards will form an acute angle. This is unlike the non-relativistic case where they travel at right angles.[30]

Classical electromagnetism

In Newtonian mechanics, the law of conservation of momentum can be derived from the law of action and reaction, which states that the forces between two particles are equal and opposite. Electromagnetic forces violate this law. Under some circumstances one moving charged particle can exert a force on another without any return force.[31] Moreover, Maxwell's equations, the foundation of classical electrodynamics, are Lorentz-invariant. However, momentum is still conserved.

Vacuum

In Maxwell's equations, the forces between particles are mediated by electric and magnetic fields. The electromagnetic force (Lorentz force) on a particle with charge q due to a combination of electric field E and magnetic field (as given by the "B-field" B) is

This force imparts a momentum to the particle, so by Newton's second law the particle must impart a momentum to the electromagnetic fields.[32]

In a vacuum, the momentum per unit volume is

where μ0 is the vacuum permeability and c is the speed of light. The momentum density is proportional to the Poynting vector S which gives the directional rate of energy transfer per unit area:[32][33]

If momentum is to be conserved in a volume V, changes in the momentum of matter through the Lorentz force must be balanced by changes in the momentum of the electromagnetic field and outflow of momentum. If Pmech is the momentum of all the particles in a volume V, and the particles are treated as a continuum, then Newton's second law gives

The electromagnetic momentum is

and the equation for conservation of each component i of the momentum is

The term on the right is an integral over the surface S representing momentum flow into and out of the volume, and nj is a component of the surface normal of S. The quantity Ti j is called the Maxwell stress tensor, defined as

Media

The above results are for the microscopic Maxwell equations, applicable to electromagnetic forces in a vacuum (or on a very small scale in media). It is more difficult to define momentum density in media because the division into electromagnetic and mechanical is arbitrary. The definition of electromagnetic momentum density is modified to

where the H-field H is related to the B-field and the magnetization M by

The electromagnetic stress tensor depends on the properties of the media.[32]

Particle in field

If a charged particle q moves in an electromagnetic field, its kinematic momentum m v is not conserved. However, it has a canonical momentum that is conserved.

Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formulation

The kinetic momentum p is different to the canonical momentum P (synonymous with the generalized momentum) conjugate to the ordinary position coordinates r, because P includes a contribution from the electric potential φ(r, t) and vector potential A(r, t):[21]

-

Classical mechanics Relativistic mechanics Lagrangian

Canonical momentum

Kinetic momentum

Hamiltonian

where ṙ = v is the velocity (see time derivative) and e is the electric charge of the particle. See also Electromagnetism (momentum). If neither φ nor A depends on position, P is conserved.[6]

The classical Hamiltonian  for a particle in any field equals the total energy of the system - the kinetic energy T = p2/2m (where p2 = p·p, see dot product) plus the potential energy V. For a particle in an electromagnetic field, the potential energy is V = eφ, and since the kinetic energy T always corresponds to the kinetic momentum p, replacing the kinetic momentum by the above equation (p = P − eA) leads to the Hamiltonian in the table.

for a particle in any field equals the total energy of the system - the kinetic energy T = p2/2m (where p2 = p·p, see dot product) plus the potential energy V. For a particle in an electromagnetic field, the potential energy is V = eφ, and since the kinetic energy T always corresponds to the kinetic momentum p, replacing the kinetic momentum by the above equation (p = P − eA) leads to the Hamiltonian in the table.

These Lagrangian and Hamiltonian expressons can derive the Lorentz force.

Canonical commutation relations

The kinetic momentum (p above) satisfies the commutation relation:[21]

where: j, k, ℓ are indices labelling vector components, Bℓ is a component of the magnetic field, and εkjℓ is the Levi-Civita symbol, here in 3-dimensions.

Quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics, momentum is defined as an operator on the wave function. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle defines limits on how accurately the momentum and position of a single observable system can be known at once. In quantum mechanics, position and momentum are conjugate variables.

For a single particle described in the position basis the momentum operator can be written as

where ∇ is the gradient operator, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and i is the imaginary unit. This is a commonly encountered form of the momentum operator, though the momentum operator in other bases can take other forms. For example, in momentum space the momentum operator is represented as

where the operator p acting on a wave function ψ(p) yields that wave function multiplied by the value p, in an analogous fashion to the way that the position operator acting on a wave function ψ(x) yields that wave function multiplied by the value x.

For both massive and massless objects, relativistic momentum is related to the de Broglie wavelength λ by

Electromagnetic radiation (including visible light, ultraviolet light, and radio waves) is carried by photons. Even though photons (the particle aspect of light) have no mass, they still carry momentum. This leads to applications such as the solar sail. The calculation of the momentum of light within dielectric media is somewhat controversial (see Abraham–Minkowski controversy).[34]

Deformable bodies and fluids

Conservation

In fields such as fluid dynamics and solid mechanics, it is not feasible to follow the motion of individual atoms or molecules. Instead, the materials must be approximated by a continuum in which there is a particle or fluid parcel at each point that is assigned the average of the properties of atoms in a small region nearby. In particular, it has a density ρ and velocity v that depend on time t and position r. The momentum per unit volume is ρv.[35]

Consider a column of water in hydrostatic equilibrium. All the forces on the water are in balance and the water is motionless. On any given drop of water, two forces are balanced. The first is gravity, which acts directly on each atom and molecule inside. The gravitational force per unit volume is ρg, where g is the gravitational acceleration. The second force is the sum of all the forces exerted on its surface by the surrounding water. The force from below is greater than the force from above by just the amount needed to balance gravity. The normal force per unit area is the pressure p. The average force per unit volume inside the droplet is the gradient of the pressure, so the force balance equation is[36]

If the forces are not balanced, the droplet accelerates. This acceleration is not simply the partial derivative ∂v/∂t because the fluid in a given volume changes with time. Instead, the material derivative is needed:[37]

Applied to any physical quantity, the material derivative includes the rate of change at a point and the changes dues to advection as fluid is carried past the point. Per unit volume, the rate of change in momentum is equal to ρDv/Dt. This is equal to the net force on the droplet.

Forces that can change the momentum of a droplet include the gradient of the pressure and gravity, as above. In addition, surface forces can deform the droplet. In the simplest case, a shear stress τ, exerted by a force parallel to the surface of the droplet, is proportional to the rate of deformation or strain rate. Such a shear stress occurs if the fluid has a velocity gradient because the fluid is moving faster on one side than another. If the speed in the x direction varies with z, the tangential force in direction x per unit area normal to the z direction is

where μ is the viscosity. This is also a flux, or flow per unit area, of x-momentum through the surface.[38]

Including the effect of viscosity, the momentum balance equations for the incompressible flow of a Newtonian fluid are

These are known as the Navier–Stokes equations.[39]

The momentum balance equations can be extended to more general materials, including solids. For each surface with normal in direction i and force in direction j, there is a stress component σij. The nine components make up the Cauchy stress tensor σ, which includes both pressure and shear. The local conservation of momentum is expressed by the Cauchy momentum equation:

where f is the body force.[40]

The Cauchy momentum equation is broadly applicable to deformations of solids and liquids. The relationship between the stresses and the strain rate depends on the properties of the material (see Types of viscosity).

Acoustic waves

A disturbance in a medium gives rise to oscillations, or waves, that propagate away from their source. In a fluid, small changes in pressure p can often be described by the acoustic wave equation:

where c is the speed of sound. In a solid, similar equations can be obtained for propagation of pressure (P-waves) and shear (S-waves).[41]

The flux, or transport per unit area, of a momentum component ρvj by a velocity vi is equal to ρ vjvj. In the linear approximation that leads to the above acoustic equation, the time average of this flux is zero. However, nonlinear effects can give rise to a nonzero average.[42] It is possible for momentum flux to occur even though the wave itself does not have a mean momentum.[43]

History of the concept

In about 530 A.D., working in Alexandria, Byzantine philosopher John Philoponus developed a concept of momentum in his commentary to Aristotle's Physics. Aristotle claimed that everything that is moving must be kept moving by something. For example, a thrown ball must be kept moving by motions of the air. Most writers continued to accept Aristotle's theory until the time of Galileo, but a few were skeptical. Philoponus pointed out the absurdity in Aristotle's claim that motion of an object is promoted by the same air that is resisting its passage. He proposed instead that an impetus was imparted to the object in the act of throwing it.[44] Ibn Sīnā (also known by his Latinized name Avicenna) read Philoponus and published his own theory of motion in The Book of Healing in 1020. He agreed that an impetus is imparted to a projectile by the thrower; but unlike Philoponus, who believed that it was a temporary virtue that would decline even in a vacuum, he viewed it as a persistent, requiring external forces such as air resistance to dissipate it.[45][46][47] The work of Philoponus, and possibly that of Ibn Sīnā,[47] was read and refined by the European philosophers Peter Olivi and Jean Buridan. Buridan, who in about 1350 was made rector of the University of Paris, referred to impetus being proportional to the weight times the speed. Moreover, Buridan's theory was different to his predecessor's in that he did not consider impetus to be self-dissipating, asserting that a body would be arrested by the forces of air resistance and gravity which might be opposing its impetus.[48][49]

René Descartes believed that the total "quantity of motion" in the universe is conserved, where the quantity of motion is understood as the product of size and speed. This should not be read as a statement of the modern law of momentum, since he had no concept of mass as distinct from weight and size, and more importantly he believed that it is speed rather than velocity that is conserved. So for Descartes if a moving object were to bounce off a surface, changing its direction but not its speed, there would be no change in its quantity of motion.[50][51] Galileo, later, in his Two New Sciences, used the Italian word impeto.

The first correct statement of the law of conservation of momentum was by English mathematician John Wallis in his 1670 work, Mechanica sive De Motu, Tractatus Geometricus: "the initial state of the body, either of rest or of motion, will persist" and "If the force is greater than the resistance, motion will result".[52] Wallis uses momentum and vis for force. Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, when it was first published in 1687, showed a similar casting around for words to use for the mathematical momentum. His Definition II defines quantitas motus, "quantity of motion", as "arising from the velocity and quantity of matter conjointly", which identifies it as momentum.[53] Thus when in Law II he refers to mutatio motus, "change of motion", being proportional to the force impressed, he is generally taken to mean momentum and not motion.[54] It remained only to assign a standard term to the quantity of motion. The first use of "momentum" in its proper mathematical sense is not clear but by the time of Jenning's Miscellanea in 1721, four years before the final edition of Newton's Principia Mathematica, momentum M or "quantity of motion" was being defined for students as "a rectangle", the product of Q and V, where Q is "quantity of material" and V is "velocity", s/t.[55]

See also

Notes

- ^ Here the time coordinate comes first. Several sources put the time coordinate at the end of the vector.

References

- ^ a b c Feynman Vol. 1, Chapter 9

- ^ "Euler's Laws of Motion". Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ McGill and King (1995). Engineering Mechanics, An Introduction to Dynamics (3rd ed.). PWS Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-93399-8.

- ^ Plastino, Angel R.; Muzzio, Juan C. (1992). "On the use and abuse of Newton's second law for variable mass problems". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy (Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers) 53 (3): 227–232. Bibcode:1992CeMDA..53..227P. doi:10.1007/BF00052611. ISSN 0923-2958. "We may conclude emphasizing that Newton's second law is valid for constant mass only. When the mass varies due to accretion or ablation, [an alternate equation explicitly accounting for the changing mass] should be used."

- ^ a b c Feynman Vol. 1, Chapter 10

- ^ a b c d e Goldstein 1980, pp. 54–56

- ^ Goldstein 1980, p. 276

- ^ Carl Nave (2010). "Elastic and inelastic collisions". Hyperphysics. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Serway, Raymond A.; John W. Jewett, Jr (2012). Principles of physics : a calculus-based text (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. p. 245. ISBN 9781133104261.

- ^ Carl Nave (2010). "Forces in car crashes". Hyperphysics. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Carl Nave (2010). "The Franck-Hertz Experiment". Hyperphysics. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ McGinnis, Peter M. (2005). Biomechanics of sport and exercise Biomechanics of sport and exercise (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL [u.a.]: Human Kinetics. p. 85. ISBN 9780736051019.

- ^ Sutton, George (2001), "1", Rocket Propulsion Elements (7th ed.), Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-32642-7

- ^ a b c Feynman Vol. 1, Chapter 11

- ^ Rindler 1986, pp. 26–27

- ^ a b Kleppner; Kolenkow. An Introduction to Mechanics. p. 135–39.

- ^ Goldstein 1980, pp. 11–13

- ^ Jackson 1975, p. 574

- ^ Feynman Vol. 3, Chapter 21-3

- ^ Goldstein 1980, pp. 20–21

- ^ a b c Lerner, Rita G., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of physics (3rd ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH-Verl. ISBN 978-3527405541.

- ^ Goldstein 1980, pp. 341–342

- ^ Goldstein 1980, p. 348

- ^ Hand, Louis N.; Finch, Janet D. (1998). Analytical mechanics (7th print ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Chapter 4. ISBN 9780521575720.

- ^ Rindler 1986, Chapter 2

- ^ Feynman Vol. 1, Chapter 15-2

- ^ Rindler 1986, pp. 77–81

- ^ Rindler 1986, p. 66

- ^ Misner, Charles W.; Kip S. Thorne, John Archibald Wheeler (1973). Gravitation. 24th printing. New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 51. ISBN 9780716703440.

- ^ Rindler 1986, pp. 86–87

- ^ Goldstein 1980, pp. 7–8

- ^ a b c d Jackson 1975, pp. 238–241 Expressions, given in Gaussian units in the text, were converted to SI units using Table 3 in the Appendix.

- ^ Feynman Vol. 1, Chapter 27-6

- ^ Barnett, Stephen M. (2010). "Resolution of the Abraham-Minkowski Dilemma". Physical Review Letters 104 (7). Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104g0401B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.070401. PMID 20366861.

- ^ Tritton 2006, pp. 48–51

- ^ Feynman Vol. 2, Chapter 40

- ^ Tritton 2006, pp. 54

- ^ Bird, R. Byron; Warren Stewart; Edwin N. Lightfoot (2007). Transport phenomena (2nd revised ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 13. ISBN 9780470115398.

- ^ Tritton 2006, p. 58

- ^ Acheson, D. J. (1990). Elementary Fluid Dynamics. Oxford University Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-19-859679-0.

- ^ Gubbins, David (1992). Seismology and plate tectonics (Repr. (with corr.) ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0521379954.

- ^ LeBlond, Paul H.; Mysak, Lawrence A. (1980). Waves in the ocean (2. impr. ed.). Amsterdam [u.a.]: Elsevier. p. 258. ISBN 9780444419262.

- ^ McIntyre, M. E. (1981). "On the 'wave momentum' myth". J. Fluid. Mech 106: 331–347.

- ^ "John Philoponus". Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 8 June 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Espinoza, Fernando (2005). "An analysis of the historical development of ideas about motion and its implications for teaching". Physics Education 40 (2): 141.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr & Mehdi Amin Razavi (1996). The Islamic intellectual tradition in Persia. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0-7007-0314-4.

- ^ a b Aydin Sayili (1987). "Ibn Sīnā and Buridan on the Motion of the Projectile". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500 (1): 477–482. Bibcode:1987NYASA.500..477S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37219.x.

- ^ T.F. Glick, S.J. Livesay, F. Wallis. "Buridian, John". Medieval Science, Technology and Medicine:an Encyclopedia. p. 107.

- ^ Park, David (1990). The how and the why : an essay on the origins and development of physical theory. With drawings by Robin Brickman (3rd print ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 9780691025087.

- ^ Daniel Garber (1992). "Descartes' Physics". In John Cottingham. The Cambridge Companion to Descartes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 310–319. ISBN 0-521-36696-8.

- ^ Rothman, Milton A. (1989). Discovering the natural laws : the experimental basis of physics ([2ème édition, revue et augmentée]. ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 83–88. ISBN 9780486261782.

- ^ Scott, J.F. (1981). The Mathematical Work of John Wallis, D.D., F.R.S. Chelsea Publishing Company. p. 111. ISBN 0-8284-0314-7.

- ^ Grimsehl, Ernst; Leonard Ary Woodward, Translator (1932). A Textbook of Physics. London, Glasgow: Blackie & Son limited. p. 78.

- ^ Rescigno, Aldo (2003). Foundation of Pharmacokinetics. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 0306477041.

- ^ Jennings, John (1721). Miscellanea in Usum Juventutis Academicae. Northampton: R. Aikes & G. Dicey. p. 67.

Further reading

- Halliday, David; Robert Resnick (1960-2007). Fundamentals of Physics. John Wiley & Sons. Chapter 9.

- Dugas, René (1988). A history of mechanics. Translated into English by J.R. Maddox (Dover ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486656328.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (2005). The Feynman lectures on physics, Volume 1: Mainly Mechanics, Radiation, and Heat (Definitive ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Pearson Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0805390469.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (2005). The Feynman lectures on physics, Volume III: Quantum Mechanics (Definitive ed.). New York: BasicBooks. ISBN 978-0805390490.

- Goldstein, Herbert (1980). Classical mechanics (2d ed.). Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. ISBN 0201029189.

- Hand, Louis N.; Finch, Janet D. Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. Chapter 4.

- Jackson, John David (1975). Classical electrodynamics (2d ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 047143132X.

- Landau, L.D.; E.M. Lifshitz (2000). The classical theory of fields. 4th rev. English edition, reprinted with corrections; translated from the Russian by Morton Hamermesh. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann. ISBN 9780750627689.

- Rindler, Wolfgang (1986). Essential Relativity : Special, general and cosmological (Rev. 2. ed.). New York u.a.: Springer. ISBN 0387100903.

- Serway, Raymond; Jewett, John (2003). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6 ed.). Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7

- Stenger, Victor J. (2000). Timeless Reality: Symmetry, Simplicity, and Multiple Universes. Prometheus Books. Chpt. 12 in particular.

- Tipler, Paul (1998). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Vol. 1: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-492-6

- Tritton, D.J. (2006). Physical fluid dynamics (2nd. ed.). Oxford: Claredon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0198544936.

External links

| Look up momentum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Conservation of momentum – A chapter from an online textbook

- MiuntePhysics - Another Physics Misconception - MinutePhysics explaining a common misconception of momentum

![\left [ p_j , p_k \right ] = \frac{i\hbar e}{c} \epsilon_{jk\ell } B_\ell](http://web.archive.org./web/20130426180142im_/http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/9/8/9/989828171b1314ed1121c3a586b12041.png)