- Order:

- Duration: 5:30

- Published: 27 Sep 2008

- Uploaded: 18 Apr 2011

- Author: wwwRSCorg

| Name | High-performance liquid chromatography |

|---|---|

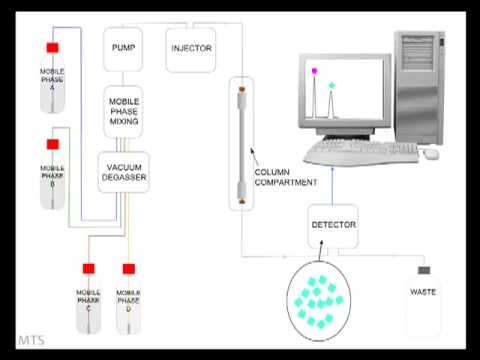

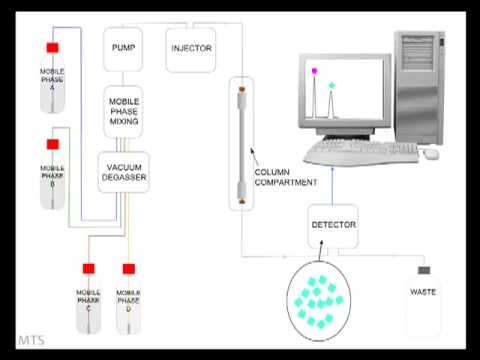

| Caption | An HPLC. From left to right: A pumping device generating a gradient of two different solvents, a steel enforced column and an apparatus for measuring the absorbance. |

| Acronym | HPLC |

| Classification | Chromatography |

| Analytes | organic moleculesbiomoleculesionspolymers |

| Related | ChromatographyAqueous Normal Phase ChromatographyIon exchange chromatographySize exclusion chromatographyMicellar liquid chromatography |

| Hyphenated | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

High-performance liquid chromatography (or high-pressure liquid chromatography, HPLC) is a chromatographic technique that can separate a mixture of compounds and is used in biochemistry and analytical chemistry to identify, quantify and purify the individual components of the mixture.

HPLC typically utilizes different types of stationary phases, a pump that moves the mobile phase(s) and analyte through the column, and a detector that provides a characteristic retention time for the analyte. The detector may also provide other characteristic information (i.e. UV/Vis spectroscopic data for analyte if so equipped). Analyte retention time varies depending on the strength of its interactions with the stationary phase, the ratio/composition of solvent(s) used, and the flow rate of the mobile phase.

With HPLC, a pump (rather than gravity) provides the higher pressure required to propel the mobile phase and analyte through the densely packed column. The increased density arises from smaller particle sizes. This allows for a better separation on columns of shorter length when compared to ordinary column chromatography.

A further refinement of HPLC is to vary the mobile phase composition during the analysis; gradient elution. A normal gradient for reversed phase chromatography might start at 5% methanol and progress linearly to 50% methanol over 25 minutes; the gradient depends on how hydrophobic the sample is. The gradient separates the sample mixtures as a function of the affinity. This partitioning process is similar to that which occurs during a liquid-liquid extraction but is continuous, not step-wise. In this example, using a water/methanol gradient, more hydrophobic components will elute (come off the column) when the mobile phase consists mostly of methanol (giving a relatively hydrophobic mobile phase).

The choice of solvents, additives and gradient depend on the nature of the column and sample. Often a series of tests are performed on the sample together with a number of trial runs in order to find the HPLC method which gives the best peak separation.

The polar analytes diffuse into a stationary water layer associated with the polar stationary phase and are thus retained. Retention strengths increase with increased analyte polarity, and the interaction between the polar analyte and the polar stationary phase (relative to the mobile phase) increases the elution time. The interaction strength depends on the functional groups in the analyte molecule which promote partitioning but can also include coulombic (electrostatic) interaction and hydrogen donor capability. Use of more polar solvents in the mobile phase will decrease the retention time of the analytes, whereas more hydrophobic solvents tend to increase retention times.

The use of more polar solvents in the mobile phase will decrease the retention time of the analytes, whereas more hydrophobic solvents tend to increase retention times. Very polar solvents in a mixture tend to deactivate the stationary phase by creating a stationary bound water layer on the stationary phase surface. This behavior is somewhat peculiar to normal phase because it is most purely an adsorptive mechanism (the interactions are with a hard surface rather than a soft layer on a surface).

Partition and NP-HPLC fell out of favor in the 1970s with the development of reversed-phase HPLC because of a lack of reproducibility of retention times as water or protic organic solvents changed the hydration state of the silica or alumina chromatographic media. Recently it has become useful again with the development of HILIC bonded phases which improve reproducibility.

Reversed phase HPLC (RP-HPLC or RPC) has a non-polar stationary phase and an aqueous, moderately polar mobile phase. One common stationary phase is a silica which has been treated with RMe2SiCl, where R is a straight chain alkyl group such as C18H37 or C8H17. With these stationary phases, retention time is longer for molecules which are more non-polar, while polar molecules elute more readily. An investigator can increase retention time by adding more water to the mobile phase; thereby making the affinity of the hydrophobic analyte for the hydrophobic stationary phase stronger relative to the now more hydrophilic mobile phase. Similarly, an investigator can decrease retention time by adding more organic solvent to the eluent. RPC is so commonly used that it is often incorrectly referred to as "HPLC" without further specification. The pharmaceutical industry regularly employs RPC to qualify drugs before their release.

RPC operates on the principle of hydrophobic forces, which originate from the high symmetry in the dipolar water structure and play the most important role in all processes in life science. RPC allows the measurement of these interactive forces. The binding of the analyte to the stationary phase is proportional to the contact surface area around the non-polar segment of the analyte molecule upon association with the ligand in the aqueous eluent. This solvophobic effect is dominated by the force of water for "cavity-reduction" around the analyte and the C18-chain versus the complex of both. The energy released in this process is proportional to the surface tension of the eluent (water: 7.3 × 10−6 J/cm², methanol: 2.2 × 10−6 J/cm²) and to the hydrophobic surface of the analyte and the ligand respectively. The retention can be decreased by adding a less polar solvent (methanol, acetonitrile) into the mobile phase to reduce the surface tension of water. Gradient elution uses this effect by automatically reducing the polarity and the surface tension of the aqueous mobile phase during the course of the analysis.

Structural properties of the analyte molecule play an important role in its retention characteristics. In general, an analyte with a larger hydrophobic surface area (C-H, C-C, and generally non-polar atomic bonds, such as S-S and others) results in a longer retention time because it increases the molecule's non-polar surface area, which is non-interacting with the water structure. On the other hand, polar groups, such as -OH, -NH2, COO- or -NH3+ reduce retention as they are well integrated into water. Very large molecules, however, can result in an incomplete interaction between the large analyte surface and the ligand's alkyl chains and can have problems entering the pores of the stationary phase.

Retention time increases with hydrophobic (non-polar) surface area. Branched chain compounds elute more rapidly than their corresponding linear isomers because the overall surface area is decreased. Similarly organic compounds with single C-C-bonds elute later than those with a C=C or C-C-triple bond, as the double or triple bond is shorter than a single C-C-bond.

Aside from mobile phase surface tension (organizational strength in eluent structure), other mobile phase modifiers can affect analyte retention. For example, the addition of inorganic salts causes a moderate linear increase in the surface tension of aqueous solutions (ca. 1.5 × 10−7 J/cm² per Mol for NaCl, 2.5 × 10−7 J/cm² per Mol for (NH4)2SO4), and because the entropy of the analyte-solvent interface is controlled by surface tension, the addition of salts tend to increase the retention time. This technique is used for mild separation and recovery of proteins and protection of their biological activity in protein analysis (hydrophobic interaction chromatography, HIC).

Another important component is the influence of the pH since this can change the hydrophobicity of the analyte. For this reason most methods use a buffering agent, such as sodium phosphate, to control the pH. The buffers serve multiple purposes: they control pH, neutralize the charge on any residual exposed silica on the stationary phase and act as ion pairing agents to neutralize charge on the analyte. Ammonium formate is commonly added in mass spectrometry to improve detection of certain analytes by the formation of ammonium adducts. A volatile organic acid such as acetic acid, or most commonly formic acid, is often added to the mobile phase if mass spectrometry is used to analyze the column eluent. Trifluoroacetic acid is used infrequently in mass spectrometry applications due to its persistence in the detector and solvent delivery system, but can be effective in improving retention of analytes such as carboxylic acids in applications utilizing other detectors, as it is one of the strongest organic acids. The effects of acids and buffers vary by application but generally improve the chromatography.

Reversed phase columns are quite difficult to damage compared with normal silica columns; however, many reversed phase columns consist of alkyl derivatized silica particles and should never be used with aqueous bases as these will destroy the underlying silica particle. They can be used with aqueous acid, but the column should not be exposed to the acid for too long, as it can corrode the metal parts of the HPLC equipment. RP-HPLC columns should be flushed with clean solvent after use to remove residual acids or buffers, and stored in an appropriate composition of solvent. The metal content of HPLC columns must be kept low if the best possible ability to separate substances is to be retained. A good test for the metal content of a column is to inject a sample which is a mixture of 2,2'- and 4,4'- bipyridine. Because the 2,2'-bipy can chelate the metal, the shape of the peak for the 2,2'-bipy will be distorted (tailed) when metal ions are present on the surface of the silica...

This technique is widely used for the molecular weight determination of polysaccharides. SEC is the official technique (suggested by European pharmacopeia) for the molecular weight comparison of different commercially available low-molecular weight heparins.

In general, ion exchangers favor the binding of ions of higher charge and smaller radius.

An increase in counter ion (with respect to the functional groups in resins) concentration reduces the retention time. An increase in pH reduces the retention time in cation exchange while a decrease in pH reduces the retention time in anion exchange.

This form of chromatography is widely used in the following applications: water purification, preconcentration of trace components, ligand-exchange chromatography, ion-exchange chromatography of proteins, high-pH anion-exchange chromatography of carbohydrates and oligosaccharides, and others.

The mobile phase composition does not have to remain constant. A separation in which the mobile phase composition is changed during the separation process is described as a gradient elution. One example is a gradient starting at 10% methanol and ending at 90% methanol after 20 minutes. The two components of the mobile phase are typically termed "A" and "B"; A is the "weak" solvent which allows the solute to elute only slowly, while B is the "strong" solvent which rapidly elutes the solutes from the column. Solvent A is often water, while B is an organic solvent miscible with water, such as acetonitrile, methanol, THF, or isopropanol.

In isocratic elution, peak width increases with retention time linearly according to the equation for N, the number of theoretical plates. This leads to the disadvantage that late-eluting peaks get very flat and broad. Their shape and width may keep them from being recognized as peaks.

Gradient elution decreases the retention of the later-eluting components so that they elute faster, giving narrower (and taller) peaks for most components. This also improves the peak shape for tailed peaks, as the increasing concentration of the organic eluent pushes the tailing part of a peak forward. This also increases the peak height (the peak looks "sharper"), which is important in trace analysis. The gradient program may include sudden "step" increases in the percentage of the organic component, or different slopes at different times – all according to the desire for optimum separation in minimum time.

In isocratic elution, the selectivity does not change if the column dimensions (length and inner diameter) change – that is, the peaks elute in the same order. In gradient elution, the elution order may change as the dimensions or flow rate change.

The driving force in reversed phase chromatography originates in the high order of the water structure. The role of the organic component of the mobile phase is to reduce this high order and thus reduce the retarding strength of the aqueous component.

This means that changing to particles that are half as big, keeping the size of the column the same, will double the performance, but increase the required pressure by a factor of four. Larger particles are used in preparative HPLC (column diameters 5 cm up to >30 cm) and for non-HPLC applications such as solid-phase extraction.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.