- Order:

- Duration: 9:02

- Published: 18 Jun 2008

- Uploaded: 05 Aug 2011

- Author: ProfASAr

- http://wn.com/Old_High_German_Languages_of_the_World_Introductory_Overvi

- Email this video

- Sms this video

![Star Wars: The Old Republic [German] [HD] Star Wars: The Old Republic [German] [HD]](http://web.archive.org./web/20110817053750im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/ioPMWW7i1nU/0.jpg)

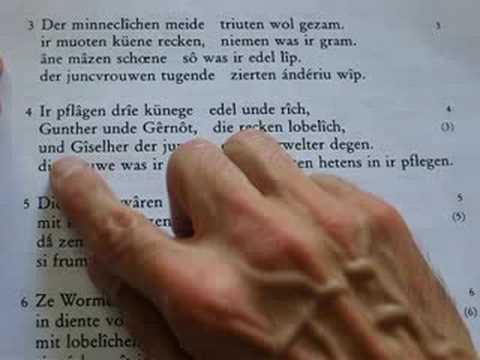

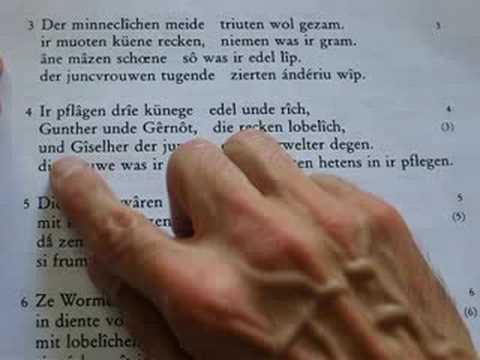

| Name | Old High German |

|---|---|

| Region | southern Germany (south of the Benrath line), parts of Austria and Switzerland, Southern Bohemia, Sporadic communities in Eastern Gaul |

| Extinct | developed into Middle High German from the 11th century |

| Familycolor | Indo-European |

| Fam2 | Germanic |

| Fam3 | West Germanic |

| Iso2 | goh |

| Iso3 | goh |

By the mid 11th century the many different vowels found in unstressed syllables had all been reduced to "e". Since these vowels were part of the grammatical endings in the nouns and verbs, their loss led to radical simplification of the inflectional grammar of German. For these reasons, 1050 is seen as the start of the Middle High German period, though in fact there are almost no texts in German for the next hundred years.

Examples of vowel reduction in unstressed syllables:

{| cellspacing="0" cellpadding="0"

|

The main dialects, with their bishoprics and monasteries:

There are some important differences between the geographical spread of the Old High German dialects and that of Modern German:

Old High German diphthongs are indicated by the digraphs ‹ei›, ‹ie›, ‹io›, ‹iu›, ‹ou›, ‹uo›.

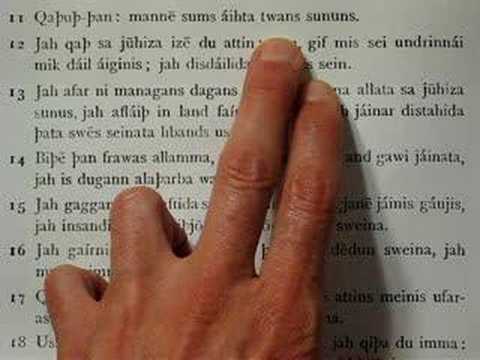

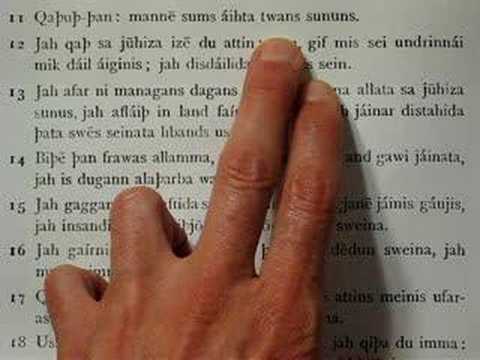

# There is wide variation in the consonant systems of the Old High German dialects arising mainly from the differing extent to which they are affected by the High German Sound Shift. Precise information about the articulation of consonants is impossible to establish. #In the plosive and fricative series, where there are two consonants in a cell, the first is fortis the second lenis. The voicing of lenis consonants varied between dialects. #Old High German distinguished long and short consonants. Double-consonant spellings don't indicate a preceding short vowel as in Modern German but true consonant gemination. Double consonants found in Old High German include pp, bb, tt, dd, ck (for ), gg, ff, ss, hh, zz, mm, nn, ll, rr. # changes to in all dialects during the 9th century. The status in the Old High German Tatian (c. 830), reflected in modern Old High German dictionaries and glossaries, is that th is found in initial position, d in other positions. # It is not clear whether Old High German had already acquired a palatized allophone following front vowels as in Modern German. #A curly-tailed z (ȥ) is sometimes used in modern grammars and dictionaries to indicate the dental fricative which arose from Common Germanic t in the High German consonant shift, to distinguish it from the dental affricate, represented as z. This distinction has no counterpart in the original manuscripts, except in the OHG Isidor, which uses tz for the affricate. # The original Germanic fricative s was in writing usually clearly distinguished from the younger fricative z that evolved from the High German consonant shift - the sounds of these two graphs seem not to have merged before the 13th century. Now seeing that s later came to be pronounced /ʃ/ before other consonants (as in Stein /ʃtaɪn/, Speer /ʃpeːɐ/, Schmerz /ʃmɛrts/ (original smerz) or the southwestern pronunciation of words like Ast /aʃt/) it seems safe to assume that the actual pronunciation of Germanic s was somewhere between [s] and [ʃ], most likely about [ɕ], in all Old High German up to late Middle High German. A word like swaz, "whatever", would thus never have been [swas] but rather [ɕwas], later (13th century) [ʃwas], [ʃvas].

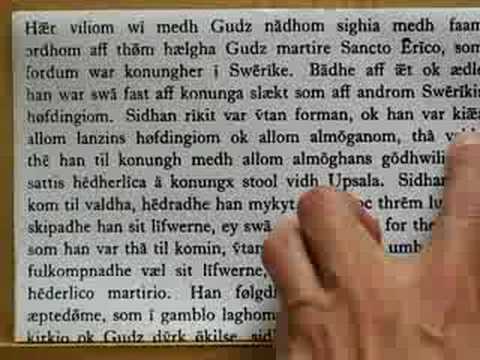

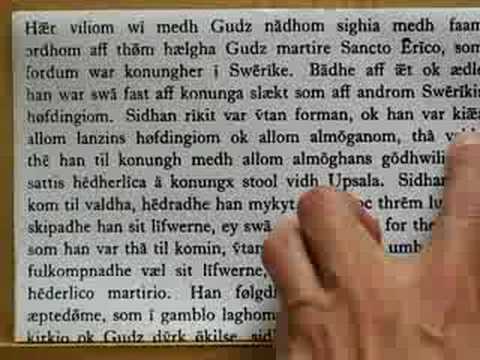

The Franks conquered Northern Gaul as far south as the Loire; the linguistic boundary later stabilised approximately along the course of the Maas and Moselle, with Frankish speakers further west being romanised.

With Charlemagne's conquest of the Lombards in 776, nearly all continental Germanic speaking peoples had been incorporated into the Frankish Empire, thus also bringing all continental West Germanic speakers under Frankish rule. However, since the language of both the administration and the Church was Latin, this unification did not lead to any development of a supra-regional variety of Frankish nor a standardized Old High German.

Old High German literacy is a product of the monasteries, notably at St. Gallen, Reichenau and Fulda. Its origins lie in the establishment of the German church by Boniface in the mid 8th century, and it was further encouraged during the Carolingian Renaissance in the 9th. The dedication to the preservation of Old High German epic poetry among the scholars of the Carolingian Renaissance was significantly greater than could be suspected from the meagre survivals we have today (less than 200 lines in total between the Lay of Hildebrand and the Muspilli). Einhard tells how Charlemagne himself ordered that the epic lays should be collected for posterity. It was the neglect or religious zeal of later generations that led to the loss of these records. Thus, it was Charlemagne's weak successor, Louis the Pious, who destroyed his father's collection of epic poetry on account of its pagan content .

Hrabanus Maurus, a student of Alcuin's and abbot at Fulda from 822, was an important advocate of the cultivation of German literacy. Among his students were Walafrid Strabo and Otfrid of Weissenburg. Notker Labeo (d. 1022) towards the end of the Old High German period was among the greatest stylists in the language, and developed a systematic orthography.

The earliest Old High German text is generally taken to be the Abrogans, a Latin-Old High German glossary variously dated between 750 and 780, probably from Reichenau. The 8th century Merseburg Incantations are the only remnant of pre-Christian German literature. The earliest texts not dependent on Latin originals would seem to be the Hildebrandslied and the Wessobrunn Prayer, both recorded in manuscripts of the early 9th century, though the texts are assumed to derive from earlier copies.

The Bavarian Muspilli is the sole survivor of what must have been a vast oral tradition. Other important works are the Evangelienbuch (Gospel harmony) of Otfrid von Weissenburg, the short but splendid Ludwigslied and the 9th century Georgslied. The boundary to Early Middle High German (from ca. 1050) is not clear-cut. The most impressive example of EMHG literature is the Annolied.

{| cellpadding="5" |----- ! Alemannic, 8th century ! South Rhine Franconian, 9th century ! East Franconian, c. 830 ! Bavarian, early 9th century |----- ! The St Gall Paternoster ! Weissenburg Catechism ! Old High German Tatian ! Freisinger Paternoster |----- | | | | |} Source: Braune/Ebbinghaus, Althochdeutsches Lesebuch, 17th edn (Niemeyer, 1994)

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.