- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Chiang Kai-Shek

http://wn.com/Chiang_Kai-Shek -

Courtney Whitney

Major General Courtney Whitney (May 20, 1897 - March 21, 1969) was an American lawyer and Army commander during World War II who later served as a senior official during the occupation of Japan.

http://wn.com/Courtney_Whitney -

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (January 26, 1880 – April 5, 1964) was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the Philippines Campaign. Arthur MacArthur, Jr., and Douglas MacArthur were the first father and son to each be awarded the medal. He was one of only five men ever to rise to the rank of general of the army in the U.S. Army, and the only man ever to become a field marshal in the Philippine Army.

http://wn.com/Douglas_MacArthur -

Emperor of Japan

The of Japan is the Japanese head of state. He is the head of the Japanese Imperial Family. He is also the highest authority of the Shinto religion. Under Japan's present constitution, the Emperor is the "symbol of the state and the unity of the people," and is a ceremonial figurehead in a constitutional monarchy (see Politics of Japan).

http://wn.com/Emperor_of_Japan -

Emperor Showa

http://wn.com/Emperor_Showa -

Harry S Truman

http://wn.com/Harry_S_Truman -

Hirohito

Hirohito (), also known as Emperor Shōwa () (Shōwa tennō), (April 29, 1901 – January 7, 1989) was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in 1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to exclusively by his posthumous name Emperor Shōwa. The word Shōwa is the name of the era that corresponded with the Emperor's reign, and was made the Emperor's own name upon his death.

http://wn.com/Hirohito -

Joji Matsumoto

was a Japanese lawyer of Meiji period specializing in commercial law.

http://wn.com/Joji_Matsumoto -

Junichiro Koizumi

is a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 2001 to 2006. He retired from politics when his term in parliament ended.

http://wn.com/Junichiro_Koizumi -

Milo Rowell

Lt. Col. Milo E. Rowell (July 25, 1903 - October 7, 1977) was an American lawyer and Army officer best known for his role in drafting the Constitution of Japan.

http://wn.com/Milo_Rowell -

Shinzo Abe

http://wn.com/Shinzo_Abe -

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War (WWII). He is widely regarded as one of the great wartime leaders. He served as prime minister twice (1940–1945 and 1951–1955). A noted statesman and orator, Churchill was also an officer in the British Army, a historian, writer, and an artist. To date, he is the only British prime minister to have received the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the first person to be recognised as an honorary citizen of the United States.

http://wn.com/Winston_Churchill

-

Japan

Japan (日本 Nihon or Nippon), officially the State of Japan ( or Nihon-koku), is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south. The characters that make up Japan's name mean "sun-origin" (because it lies to the east of nearby countries), which is why Japan is sometimes referred to as the "Land of the Rising Sun".

http://wn.com/Japan -

United States

The United States of America (also referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district. The country is situated mostly in central North America, where its forty-eight contiguous states and Washington, D.C., the capital district, lie between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The state of Alaska is in the northwest of the continent, with Canada to the east and Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. The state of Hawaii is an archipelago in the mid-Pacific. The country also possesses several territories in the Caribbean and Pacific.

http://wn.com/United_States

- 1890

- 1947

- 26 July

- 3 May

- absolute monarchy

- Academic freedom

- Beate Sirota

- bicameral

- Bushi-Dō

- Cabinet (government)

- Cabinet of Japan

- Censorship in Japan

- Chiang Kai-Shek

- Christian

- compulsory education

- constitution

- Constitutionalism

- Courtney Whitney

- de jure

- Diet (assembly)

- Diet of Japan

- double jeopardy

- Douglas MacArthur

- due process

- election

- Emperor of Japan

- Emperor Showa

- ex post facto

- fair trial

- Filing (legal)

- flagrante delicto

- forced marriage

- Freedom of assembly

- Freedom of choice

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Freedom of thought

- general election

- Government of Japan

- habeas corpus

- Harry S Truman

- head of state

- Hirohito

- human rights

- international law

- Japan

- Japanese Buddhism

- Japanese nationalism

- Joji Matsumoto

- Judicial review

- Junichiro Koizumi

- Kijuro Shidehara

- Kyūjitai

- liberal democracy

- liberalism

- liberty

- lèse-majesté

- majority

- Matsumoto Commission

- Meiji Constitution

- Meiji Restoration

- Militarism

- Milo Rowell

- occupied Japan

- parliamentary system

- peerage

- postwar Japan

- Potsdam Declaration

- Prime Minister

- Privy Council

- Prussia

- public trial

- public welfare

- referendum

- reserve power

- Right to petition

- Robert E. Ward

- Save Article 9

- search and seizure

- secret ballot

- self-incrimination

- Shinjitai

- Shintō

- Shinzo Abe

- slavery

- Social equality

- sovereignty

- super majority

- tax

- torture

- trade union

- treaty

- unicameral

- United Nations

- United States

- upper house

- Winston Churchill

- Workers' rights

- World War II

- Yasuhiro Nakasone

- Yomiuri Shimbun

- Yoshida Shigeru

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:57

- Published: 02 Mar 2009

- Uploaded: 26 Oct 2011

- Author: ultimateinfinity1985

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:07

- Published: 06 Jun 2009

- Uploaded: 17 Apr 2011

- Author: reynoldsair

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:48

- Published: 06 May 2009

- Uploaded: 28 Nov 2011

- Author: CommunistPartyJapan

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:39

- Published: 30 Jun 2009

- Uploaded: 15 Feb 2011

- Author: JapanSocietyNYC

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:48

- Published: 06 Aug 2006

- Uploaded: 22 Oct 2009

- Author: lordzombie

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:42

- Published: 02 Feb 2009

- Uploaded: 17 Jun 2011

- Author: artlinefilms

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:00

- Published: 31 Jan 2008

- Uploaded: 10 Jan 2011

- Author: notcricketer

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:06

- Published: 07 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 18 Oct 2011

- Author: RevolutionNewsUS

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:50

- Published: 24 Jul 2007

- Uploaded: 03 Dec 2011

- Author: section6nakamura

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:13

- Published: 03 Nov 2010

- Uploaded: 22 Oct 2011

- Author: edtheball69

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:06

- Published: 23 Jan 2010

- Uploaded: 10 Sep 2010

- Author: lyricallily

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:01

- Published: 27 Jan 2011

- Uploaded: 30 Oct 2011

- Author: smokingman83

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:20

- Published: 28 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Dec 2011

- Author: astonisher1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:24

- Published: 29 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 20 Apr 2011

- Author: astonisher1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:21

- Published: 29 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 08 May 2011

- Author: astonisher1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:21

- Published: 29 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 19 Apr 2011

- Author: astonisher1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:26

- Published: 29 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 29 Sep 2011

- Author: astonisher1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:32

- Published: 26 Sep 2010

- Uploaded: 04 Dec 2011

- Author: MiradaAtlantica

- 1868

- 1890

- 1947

- 26 July

- 3 May

- absolute monarchy

- Academic freedom

- Beate Sirota

- bicameral

- Bushi-Dō

- Cabinet (government)

- Cabinet of Japan

- Censorship in Japan

- Chiang Kai-Shek

- Christian

- compulsory education

- constitution

- Constitutionalism

- Courtney Whitney

- de jure

- Diet (assembly)

- Diet of Japan

- double jeopardy

- Douglas MacArthur

- due process

- election

- Emperor of Japan

- Emperor Showa

- ex post facto

- fair trial

- Filing (legal)

- flagrante delicto

- forced marriage

- Freedom of assembly

- Freedom of choice

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Freedom of thought

- general election

- Government of Japan

- habeas corpus

- Harry S Truman

- head of state

- Hirohito

- human rights

- international law

- Japan

- Japanese Buddhism

- Japanese nationalism

- Joji Matsumoto

- Judicial review

- Junichiro Koizumi

- Kijuro Shidehara

- Kyūjitai

- liberal democracy

- liberalism

- liberty

- lèse-majesté

- majority

- Matsumoto Commission

size: 5.4Kb

size: 2.5Kb

size: 11.3Kb

size: 1.9Kb

size: 9.3Kb

size: 3.5Kb

size: 8.5Kb

size: 3.1Kb

Outline

The constitution provides for a parliamentary system of government and guarantees certain fundamental rights. Under its terms the Emperor of Japan is "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people" and exercises a purely ceremonial role without the possession of sovereignty.The constitution, also known as the or the , is most characteristic and famous for the renunciation of the right to wage war contained in Article 9 and to a lesser extent, the provision for de jure popular sovereignty in conjunction with the monarchy.

The constitution was drawn up under the Allied occupation that followed World War II and was intended to replace Japan's previous militaristic and absolute monarchy system with a form of liberal democracy. Currently, it is a rigid document and no subsequent amendment has been made to it since its adoption.

Historical origins

Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan of 1890 (commonly called the "Meiji Constitution", after the emperor during whose reign it was composed), was the fundamental law of the former state. Enacted after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, it provided for a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy, based jointly on the Prussian and British models. In theory, the Emperor of Japan or Tenno was the supreme ruler, and the Cabinet, whose Prime Minister would be elected by a Privy Council, were his followers; in practice, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime Minister was the actual head of government. Under the Meiji Constitution, the Prime Minister and his Cabinet were not necessarily chosen from the elected members of the Diet. Pursuing the regular amending procedure of the "Meiji Constitution", it was entirely revised to become the "Postwar Constitution" on 3 November 1946. The Postwar Constitution has been in force since 3 May 1947.

The Potsdam Declaration

On 26 July 1945, Allied leaders Winston Churchill, Harry S Truman, and Chiang Kai-Shek issued the Potsdam Declaration, which demanded Japan's unconditional surrender. This declaration also defined the major goals of the postsurrender Allied occupation: "The Japanese government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established" (Section 10). In addition, the document stated: "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government" (Section 12). The Allies sought not merely punishment or reparations from a militaristic foe, but fundamental changes in the nature of its political system. In the words of political scientist Robert E. Ward: "The occupation was perhaps the single most exhaustively planned operation of massive and externally directed political change in world history."

Drafting process

The wording of the Potsdam Declaration—"The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles..."—and the initial postsurrender measures taken by Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), suggest that neither he nor his superiors in Washington intended to impose a new political system on Japan unilaterally. Instead, they wished to encourage Japan's new leaders to initiate democratic reforms on their own. But by early 1946, MacArthur's staff and Japanese officials were at odds over the most fundamental issue, the writing of a new constitution. Emperor Showa (known to the West as Hirohito), Prime Minister Shidehara Kijuro and most of the cabinet members were extremely reluctant to take the drastic step of replacing the 1889 Meiji Constitution with a more liberal document. In late 1945, Shidehara appointed Joji Matsumoto, state minister without portfolio, head of a blue-ribbon committee of constitutional scholars to suggest revisions. The Matsumoto Commission's recommendations, made public in February 1946, were quite conservative (described by one Japanese scholar in the late 1980s as "no more than a touching-up of the Meiji Constitution"). MacArthur rejected them outright and ordered his staff to draft a completely new document.

Much of it was drafted by two senior army officers with law degrees: Milo Rowell and Courtney Whitney, though others chosen by MacArthur also had a large say in the document. The articles about equality between men and women are reported to be written by Beate Sirota. Although the document's authors were non-Japanese, they took into account the Meiji Constitution, the demands of Japanese lawyers, and the opinions of pacifist political leaders such as Shidehara and Yoshida Shigeru. MacArthur gave the authors less than a week to complete the draft, which was presented to surprised Japanese officials on 13 February 1946. On 6 March 1946 the government publicly disclosed an outline of the pending constitution. On 10 April elections were held to the House of Representatives of the Ninetieth Imperial Diet, which would consider the proposed constitution. The election law having been changed, this was the first general election in Japan in which women were permitted to vote.

The MacArthur draft, which proposed a unicameral legislature, was changed at the insistence of the Japanese to allow a bicameral legislature, both houses being elected. In most other important respects, however, the ideas embodied in the 13 February document were adopted by the government in its own draft proposal of 6 March. These included the constitution's most distinctive features: the symbolic role of the Emperor, the prominence of guarantees of civil and human rights, and the renunciation of war.

Adoption

It was decided that in adopting the new document the Meiji Constitution would not be violated, but rather legal continuity would be maintained. Thus the 1946 constitution was adopted as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution in accordance with the provisions of Article 73 of that document. Under Article 73 the new constitution was formally submitted to the Imperial Diet by the Emperor, through an imperial rescript issued on 20 June. The draft constitution was submitted and deliberated upon as the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution. The old constitution required that the bill receive the support of a two-thirds majority in both houses of the Diet in order to become law. After both chambers had made some amendments the House of Peers approved the document on 6 October; it was adopted in the same form by the House of Representatives the following day, with only five members voting against, and finally became law when it received the Emperor's assent on 3 November. Under its own terms the constitution came into effect six months later on 3 May 1947.

Early proposals for amendment

The new constitution would not have been written the way it was had MacArthur and his staff allowed Japanese politicians and constitutional experts to resolve the issue as they wished. The document's foreign origins have, understandably, been a focus of controversy since Japan recovered its sovereignty in 1952. Yet in late 1945 and 1946, there was much public discussion on constitutional reform, and the MacArthur draft was apparently greatly influenced by the ideas of certain Japanese liberals. The MacArthur draft did not attempt to impose a United States-style presidential or federal system. Instead, the proposed constitution conformed to the British model of parliamentary government, which was seen by the liberals as the most viable alternative to the European absolutism of the Meiji Constitution.After 1952 conservatives and nationalists attempted to revise the constitution to make it more "Japanese", but these attempts were frustrated for a number of reasons. One was the extreme difficulty of amending it. Amendments require approval by two-thirds of the members of both houses of the National Diet before they can be presented to the people in a referendum (Article 96). Also, opposition parties, occupying more than one-third of the Diet seats, were firm supporters of the constitutional status quo. Even for members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the constitution was advantageous. They had been able to fashion a policy-making process congenial to their interests within its framework. Yasuhiro Nakasone, a strong advocate of constitutional revision during much of his political career, for example, downplayed the issue while serving as prime minister between 1982 and 1987.

Main provisions

Structure

The constitution has a length of approximately 5,000 words. It consists of a preamble and 103 articles grouped into eleven chapters. These are:

Founding principles

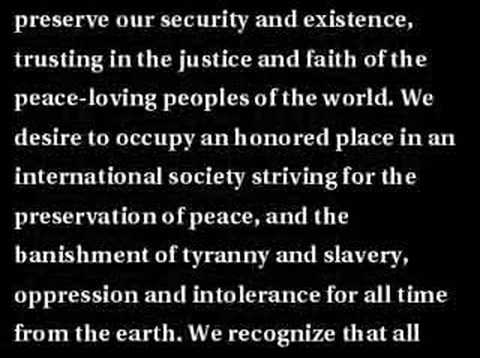

The constitution contains a firm declaration of the principle of popular sovereignty in the preamble. This is proclaimed in the name of the "Japanese people" and declares that "sovereign power resides with the people" and:government is a sacred trust of the people, the authority for which is derived from the people, the powers of which are exercised by the representatives of the people, and the benefits of which are enjoyed by the people.

Part of the purpose of this language is to refute the previous constitutional theory that sovereignty resided in the Emperor. The constitution asserts that the Emperor is merely a symbol and that he derives "his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power" (Article 1). The text of the constitution also asserts the liberal doctrine of fundamental human rights. In particular Article 97 states that

:the fundamental human rights by this Constitution guaranteed to the people of Japan are fruits of the age-old struggle of man to be free; they have survived the many exacting tests for durability and are conferred upon this and future generations in trust, to be held for all time inviolate.

Organs of government

: Main article: Government of JapanThe constitution establishes a parliamentary system of government. The Emperor carries out most of the functions of a head of state but his role is merely ceremonial and, unlike the forms of constitutional monarchy found in some other nations, he possesses no reserve powers. Legislative authority is vested in a bicameral National Diet and, whereas previously the upper house had consisted of members of the nobility, the new constitution provided that both chambers be directly elected. Executive authority is exercised by a Prime Minister and cabinet answerable to the legislature, while the judiciary is headed by a Supreme Court.

Individual rights

"The rights and duties of the people" are prominently featured in the postwar constitution. Altogether, thirty-one of its 103 articles are devoted to describing them in considerable detail, reflecting the commitment to "respect for the fundamental human rights" of the Potsdam Declaration. Although the Meiji Constitution had a section devoted to the "rights and duties of subjects", which guaranteed "liberty of speech, writing, publication, public meetings, and associations", these rights were granted "within the limits of law". Freedom of religious belief was allowed "insofar as it does not interfere with the duties of subjects" (all Japanese were required to acknowledge the Emperor's divinity, and those, such as Christians, who refused to do so out of religious conviction were accused of lèse-majesté). Such freedoms are delineated in the postwar constitution without qualification.Individual rights under the Japanese constitution are rooted in Article 13 where the constitution asserts the right of the people "to be respected as individuals" and, subject to "the public welfare", to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." This article's core notion is jinkaku, which represents "the elements of character and personality that come together to define each person as an individual," and which represents the aspects of each individual's life that the government is obligated to respect in the exercise of its power.

Subsequent provisions provide for:

Other provisions

Amendments and revisions

The constitution has not been amended since its 1947 enactment. Article 96 provides that amendments can be made to any part of the constitution. However, a proposed amendment must first be approved by both houses of the Diet, by at least a super majority of two-thirds of each house (rather than just a simple majority). It must then be submitted to a referendum in which it is sufficient for it to be endorsed by a simple majority of votes cast. A successful amendment is finally promulgated by the Emperor, but the monarch cannot veto an amendment.Some commentators have suggested that the difficulty of the amendment process was favoured by the constitution's American authors from a desire that the fundamentals of the regime they had imposed would be resistant to change. However, among Japanese themselves, any change to the document and to the post-war settlement it embodies is highly controversial. From the 1960s to the 1980s, constitutional revision was rarely debated. In the 1990s, right-leaning and conservative voices broke some taboos, for example, when the Yomiuri Shimbun published a suggestion for constitutional revision in 1994. This period saw a number of right-leaning groups forming to aggressively push for constitutional revision, but also a significant number of organizations and individuals speaking out against revision and in support of "the peace constitution."

The debate has been highly polarized. The most controversial issues are proposed changes to Article 9, the "peace article" and provisions relating to the role of the Emperor. Progressive, left, center-left and peace movement related individuals and organizations, as well as the opposition parties, labor and youth groups advocate keeping (and even strengthening) the existing constitution in these areas, while right-leaning, nationalist and/or conservative groups and individuals advocate changes to increase the prestige of the Emperor (though not granting him political powers) and to allow a more aggressive stance of the self-defense force, e.g. by turning it officially into a military. Others areas of the constitution and connected laws discussed for potential revision relate to the status of women, the education system and the system of public corporations (including social welfare, non-profit and religious organizations as well as foundations), and structural reform of the election process, e.g. to allow for direct election of the prime minister. There are countless grassroots groups, associations, NGOs, think tanks, scholars, and politicians speaking out in favor of one or the other side of the issue.

In August 2005, the then Japanese Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi, proposed an amendment to the constitution in order to increase Japan's Defence Forces' roles in international affairs. A draft of the proposed constitution was released by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on 22 November 2005 as part of the fiftieth anniversary of the party's founding. The proposed changes included:

This draft fanned the debate, with strong opposition coming even from non-governmental organisations of other countries, as well as established and newly formed grassroots Japanese organisations, such as Save Article 9. Per the current constitution, a proposal for constitutional changes must be passed by a two-thirds vote in the Diet, then be put to a national referendum. However, there was in 2005 no legislation in place for such a referendum.

Koizumi's successor, Shinzo Abe vowed to push aggressively for constitutional revision. A major step toward this was getting legislation passed to allow for a national referendum in April 2007. However, by that time there was little public support for changing the constitution, with a survey showing 34.5% of Japanese not wanting any changes, 44.5% wanting no changes to Article 9, and 54.6% supporting the current interpretation on self-defense. On the 60th anniversary of the constitution, on 3 May 2007, thousands took to the streets in support of Article 9. The Chief Cabinet secretary and other top government officials interpreted the survey to mean that the public wants a pacifist Constitution that renounces war, and may need to be better informed about the details of the revision debate. The legislation passed by parliament specifies that a referendum on constitutional reform could take place at the earliest in 2010, and would need approval from a majority of voters.

Human rights guarantees in practice

: See also: Human rights in JapanInternational bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Amnesty International have argued that many of the guarantees for individual rights contained in the Japanese constitution have not been effective in practice. Such critics have also argued that, contrary to Article 98, and its requirement that international law be treated as part of the domestic law of the state, human rights treaties to which Japan is a party are seldom enforced in Japanese courts.

Despite constitutional guarantees of the right to a fair trial, conviction rates in Japan approach 99%. In one study, the conviction rate in contested Japanese trials in 1994 was found to be 98.8%, while the comparable conviction rate in contested United States federal trials in 1994 was 30.9%. The study concluded that this was due to the limited budgets for prosecutors in Japan compared to the United States, leading them to prosecute only the most solid cases, rather than due to bias by judges.

See also

Notes and references

External links

Category:Government of Japan Japan Category:Postwar Japan Category:Japanese law Category:1947 in law

ar:دستور اليابان ca:Constitució del Japó de:Japanische Verfassung el:Σύνταγμα της Ιαπωνίας es:Constitución de Japón fa:قانون اساسی ژاپن fr:Constitution du Japon ko:일본국 헌법 hy:Ճապոնիայի պետական և սահմանադրական կարգը hi:जापान का संविधान id:Konstitusi Jepang it:Costituzione del Giappone ka:იაპონიის კონსტიტუცია lt:Japonijos Konstitucija hu:Japán alkotmánya ms:Perlembagaan Jepun mn:Японы Үндсэн Хууль nl:Japanse Grondwet ja:日本国憲法 no:Japans grunnlov pl:Konstytucja Japonii pt:Constituição do Japão ru:Конституция Японии fi:Japanin perustuslaki sv:Japans konstitution tl:Saligang Batas ng Hapon tr:Japon Anayasası uk:Конституція Японії vi:Hiến pháp Nhật Bản zh:日本国宪法This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.