-

Ak Koyunlu

The Ak Koyunlu or Aq Qoyunlu, also called the White Sheep Turkomans (, , Ottoman Turkish: آق قوينلى, ), was an Oghuz Turkic tribal federation, that ruled parts of present-day Eastern Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, northern Iraq, and Iran from 1378 to 1508.

http://wn.com/Ak_Koyunlu -

Anania Shirakatsi

Anania Shirakatsi (, , also known as Ananias of Shirak; 610 – 685) was an Armenian mathematician, astronomer and geographer. He is commonly attributed to having written the Geography (Ashkharhatsuyts, in Armenian).

http://wn.com/Anania_Shirakatsi -

Armenians

Armenian people or Armenians (, hayer) are a nation and ethnic group native to the Caucasus and the Armenian Highland.

http://wn.com/Armenians -

Assyrian people

The Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac people (frequently known as Assyrians, Syriacs, Syriac Christians, Suroye/Suryoye, Chaldeans, and other variants, see names of Syriac Christians) are an ethnic group whose origins lie in the Fertile Crescent. Today that ancient territory is part of several nations; the Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac people have been minorities under other ethnic groups' rule since the early Middle Ages. They have traditionally lived in northern Iraq, Syria, northwest Iran, and Turkey's Southeastern Anatolia. Many have migrated to the Caucasus, North America and Europe during the past century. The major sub-ethnic division is between an Eastern group ("Nestorians" and "Chaldean Christians") and a Western one ("Syrian Jacobites").

http://wn.com/Assyrian_people -

Azerbaijani people

The Azerbaijanis(; in Azeri: Azərbaycanlılar, Azeris/Azərilər, Azeri Turks/Azərilər; Azeri Cyrillic: Азәриләр, Azeri: آذری لر ) or Azarbaijanis are an ethnic group mainly living in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Commonly referred to as Azeris/Āzarīs (آذری - Azərilər) or Azerbaijani Turks (), they also live in a wider area from the Caucasus to the Iranian plateau. The Azeris are predominantly Shia Muslim and have a mixed heritage of Turkic, Caucasian and Iranic elements.

http://wn.com/Azerbaijani_people -

Bagrat Ulubabyan

Bagrat Arshaki Ulubabyan (; ; December 9, 1925 – November 19, 2001) was an Armenian writer and historian, known most prominently for his work on the histories of Nagorno-Karabakh and Artsakh.

http://wn.com/Bagrat_Ulubabyan -

Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon ( hanja:潘基文; born 13 June 1944) is the eighth and current Secretary-General of the United Nations, after succeeding Kofi Annan in 2007. Before becoming Secretary-General, Ban was a career diplomat in South Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in the United Nations. He entered diplomatic service the year he graduated from university, accepting his first post in New Delhi, India. In the foreign ministry he established a reputation for modesty and competence.

http://wn.com/Ban_Ki-moon -

Chechnya

The Chechen Republic (; , Chechenskaya Respublika; , Noxçiyn Respublika), or, informally, Chechnya (; ; , Noxçiyçö), sometimes referred to as Ichkeria, Chechnia, Chechenia or Noxçiyn, is a federal subject of Russia. It is located in southeastern part of Europe, in the Northern Caucasus mountains, in the North Caucasian Federal District. As of 1 January 2010, the population was 1,267,740 (according to Russian State statistics).

http://wn.com/Chechnya -

Davtak Kertogh

Davtak Kertogh (Davtak the Poet) was a 7th century Armenian poet, the first secular writer in Armenian literature. He is the author of "Elegy on the Death of the Great Prince Jevansher", dedicated to the first Sassanid Persian prince of Caucasian Albania, who accepted Christianity and was murdered.

http://wn.com/Davtak_Kertogh -

Dmitry Medvedev

Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev (; born 14 September 1965) is the third and current President of the Russian Federation, inaugurated on 7 May 2008. He won the presidential election held on 2 March 2008 with 71.25% of the popular vote.

http://wn.com/Dmitry_Medvedev -

Erekle II

Erekle II () (November 7, 1720, or October 7, 1721 [according to C. Toumanoff] — January 11, 1798) was a Georgian monarch of the Bagrationi Dynasty, reigning as the king of Kakheti from 1744 to 1762, and of Kartli and Kakheti from 1762 until 1798. In the contemporary Persian sources he is referred to as Erekli Khan, while Russians knew him as Irakli (Irakly). His name is frequently transliterated in a Latinized form Heraclius.

http://wn.com/Erekle_II -

Estakhri

Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn Muhammad al-Farisi al Istakhri (aka Estakhri, Persian: استخری, i.e. from the city of Estakhr) was a medieval Persian geographer in the 10th century.

http://wn.com/Estakhri -

Evgeni Kirilov

Evgeni Zahariev Kirilov () (born 26 January 1945 in Lubichevo, Targovishte Oblast) is a Bulgarian politician and Member of the European Parliament. He is a member of the Coalition for Bulgaria, part of the Party of European Socialists, and became an MEP on 1 January 2007 with the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union.

http://wn.com/Evgeni_Kirilov -

Greek people

http://wn.com/Greek_people -

Hayk

Hayk,Haig (, also transliterated as Haik) is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation. His story is told in the History attributed to Moses of Chorene (5th to 7th century).

http://wn.com/Hayk -

Hethumids

The Hethumids (also spelled Hetoumids or '''Het'umids), also known as the House of Lampron''' (after Lampron castle), were the rulers of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia from 1226 to 1373. Hethum I, the first of the Hethumids, came to power when he married Queen Isabella of Armenia who had inherited the throne from her father.

http://wn.com/Hethumids -

Heydar Aliyev

Heydar Alirza oglu Aliyev (, ; May 10, 1923 – December 12, 2003), also spelled as Heidar Aliev, Geidar Aliev, Haydar Aliyev, Geydar Aliyev was the third President of Azerbaijan for the New Azerbaijan Party from June 1993 to October 2003, when his son Ilham Aliyev succeeded him.

http://wn.com/Heydar_Aliyev -

Ibrahim Khalil Khan

Ibrahim Khalil khan Javanshir (1730–1806) was the Azeri Turkic khan of Karabakh from the Javanshir family, who succeeded his father Panah-Ali khan Javanshir as the ruler of Karabakh khanate.

http://wn.com/Ibrahim_Khalil_Khan -

Ilham Aliyev

Ilham Heydar oglu Aliyev (, born 24 December 1961) is the fourth and current President of Azerbaijan. He also functions as the Chairman of the New Azerbaijan Party.

http://wn.com/Ilham_Aliyev -

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are people, communities, and nations who claim a historical continuity and cultural affinity with societies endemic to their original territories that developed prior to exposure to the larger connected civilization associated with Western culture. These societies therefore consider themselves distinct from societies of the majority culture/s that have contested their cultural sovereignty and self-determination.

http://wn.com/Indigenous_peoples -

Israel Ori

Israel Ori () (1658–1711) was a prominent figure of the Armenian national liberation movement and a diplomat that sought the liberation of Armenia from Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

http://wn.com/Israel_Ori -

Ivan Bagramyan

http://wn.com/Ivan_Bagramyan -

Ivan Gudovich

Count Ivan Vasilyevich Gudovich (Russian, in full: граф Иван Васильевич Гудович) (1741–1820) was a Russian noble and military leader of Ukrainian descent. His exploits included the capture of Khadjibey (1789) and the conquest of maritime Dagestan (1807).

http://wn.com/Ivan_Gudovich -

Ivan Isakov

Hovhannes Stepani Isakov (, , Ivan Stepanovich Isakov; ( – October 11, 1967) was a Soviet Armenian military commander, chief of staff and Admiral of the Fleet in the Soviet Navy. He played a crucial role in shaping the Soviet navy, particularly the Baltic and Black Sea flotillas during the Second World War. Asides from his military career, Isakov became a member and writer of the oceanographic committee of the Soviet Union Academy of Sciences in 1958 and in 1967, became an honorary member of that of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic's Academy of Sciences.

http://wn.com/Ivan_Isakov -

Johann Schiltberger

Johann (Hans) Schiltberger (May 9, 1381 – c. 1440) was a German traveller and writer. He was born of a noble family, probably at Hollern near Lohhof halfway between Munich and Freising.

http://wn.com/Johann_Schiltberger -

Joseph Emin

Joseph Emin (, Hovsep Emin) (1726 - August 2, 1809, Calcutta), was a prominent figure of the Armenian national liberation movement who travelled to various European countries and Russia in order to secure support for the liberation of Armenia from Persia and the Ottoman Empire. He married Thangoom-Khatoon (1748 - 14 September 1843) in 1776, whose grave lies next to his.

http://wn.com/Joseph_Emin -

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (18 December 1878 – 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and head of state who served as the first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee from 1922 until his death in 1953. After the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924, Stalin rose to become the leader of the Soviet Union, which he ruled as a dictator.

http://wn.com/Joseph_Stalin -

Kara Koyunlu

The Kara Koyunlu or Qara Qoyunlu, also called the Black Sheep Turkomans (Azerbaijani:قه ره قویونلو / Qaraqoyunlu; Persian: قرا قویونلو ; Turkish: Karakoyunlu); , were a Shi'ite Oghuz Turkic tribal federation that ruled over the territory comprising the present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, north western Iran, eastern Turkey and Iraq from about 1375 to 1468.

http://wn.com/Kara_Koyunlu -

Kura-Araxes culture

The Kura-Araxes culture or the Early trans-Caucasian culture, was a civilization that existed from 3400 B.C until about 2000 B.C. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; thence it spread to Georgia by 3000 B.C., and during the next millennium it proceeded westward to the Erzurum plain, southwest to Cilicia, and to the southeast into an area below the Urmia basin and Lake Van, down to the borders of present day Syria. Altogether, the early Trans-Caucasian culture, at its greatest spread, enveloped a vast area approximately 1000 km by 500 km.

http://wn.com/Kura-Araxes_culture -

Kurds

http://wn.com/Kurds -

Levon Ter-Petrossian

Levon Ter-Petrossian (; ) (born January 9, 1945), sometimes transliterated Levon Ter-Petrosyan or Ter-Petrosian (with or without the hyphen), was the first President of Armenia from 1991 to 1998. Due to some economic and political problems, he resigned on February 3, 1998 and was succeeded by Robert Kocharyan.

http://wn.com/Levon_Ter-Petrossian -

Louis Figuier

Louis Figuier (1819-1894) was a French scientist and writer. He was the nephew of Pierre-Oscar Figuier and became Professor of chemistry at L'Ecole de

http://wn.com/Louis_Figuier -

Louis XIV of France

| align=right

http://wn.com/Louis_XIV_of_France -

Mesrob Mashtots

http://wn.com/Mesrob_Mashtots -

Movses Baghramian

Movses Baghramian (birth and death dates are unknown) was a 18th century Armenian liberation movement leader.

http://wn.com/Movses_Baghramian -

Nader Shah

Nāder Shāh Afshār (; also known as Nāder Qoli Beg - نادر قلی بیگ or Tahmāsp Qoli Khān - تهماسپ قلی خان) (November, 1688 or August 6, 1698 – June 19, 1747) ruled as Shah of Iran (1736–47) and was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty. Because of his military genius, some historians have described him as the Napoleon of Persia or the Second Alexander. Nader Shah was a member of the Turkic Afshar tribe of northern Persia, which had supplied military power to the Safavid state since the time of Shah Ismail I.

http://wn.com/Nader_Shah -

Napoléon Bonaparte

http://wn.com/Napoléon_Bonaparte -

Ottoman Empire

The Sublime Ottoman State (Ottoman Turkish, Persian: دَوْلَتِ عَلِيّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه Devlet-i ʿAliyye-yi ʿOsmâniyye, Modern Turkish: Yüce Osmanlı Devleti or Osmanlı İmparatorluğu) was an empire that lasted from 1299 to 1923.

http://wn.com/Ottoman_Empire -

Panah Ali Khan

Panah-Ali khan Javanshir (1693, Sarijali – 1761, Shiraz, Iran) was the founder and first ruler of Karabakh khanate, initially under nominal Persian suzeiranty and by 1748 an independent feudal state that existed in 1747–1822 in Karabakh and adjacent areas.

http://wn.com/Panah_Ali_Khan -

Paul I of Russia

Paul I (; Pavel Petrovich) ( – ) was the Emperor of Russia between 1796 and 1801.

http://wn.com/Paul_I_of_Russia -

Pavel Tsitsianov

Pavel Dmitriyevich Tsitsianov (; ; , Moscow—) was the Georgian Imperial Russian military commander and infantry general from 1804. A member of the noble Georgian family Tsitsishvili (Georgian: ციციშვილი), Tsitsianov participated in suppression of the Kościuszko Uprising and in the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813). In 1802 he became the head of the Russian troops in Georgia. He was assassinated outside Baku in 1806.

http://wn.com/Pavel_Tsitsianov -

Peter the Great

Peter I the Great or Pyotr Alexeyevich Romanov () ( – ) ruled Russia and later the Russian Empire from until his death, jointly ruling before 1696 with his weak and sickly half-brother, Ivan V.

http://wn.com/Peter_the_Great -

Petr Ivanovich Panin

General Count Petr Ivanovich Panin () (1721 – April 26, 1789), younger brother of Nikita Ivanovich Panin, fought with distinction in the Seven Years' War and in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, capturing Bender on September 26, 1770. In 1773–1775 he participated in suppressing Pugachev's rebellion. He died in Moscow, as the senior General of the Russian Army. He is a father of Nikita Petrovich Panin.

http://wn.com/Petr_Ivanovich_Panin -

Pope Innocent XII

Pope Innocent XII (13 March 1615 – 27 September 1700), born Antonio Pignatelli, was Pope from 1691 to 1700. He was the successor of Pope Alexander VIII (1689–91).

http://wn.com/Pope_Innocent_XII -

Robert H. Hewsen

Robert H. Hewsen is Professor Emeritus of History at Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey and is an expert on the ancient history of the South Caucasus.

http://wn.com/Robert_H_Hewsen -

Seljuk Turks

http://wn.com/Seljuk_Turks -

Sergei Khudyakov

Sergei Alexandrovich Khudyakov (; – April 18, 1950), born Armenak Artem Khanferiants (), was a Soviet Armenian chief Marshal of the Air Force.

http://wn.com/Sergei_Khudyakov -

Strabo

Strabo (; 63/64 BC – ca. AD 24) was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.

http://wn.com/Strabo -

Turkic language

http://wn.com/Turkic_language -

Turkmen people

The Turkmen (Türkmen or Түркмен, plural Türkmenler or Түркменлер) are a Turkic people located primarily in the Central Asian states of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, northern Iraq and in northeastern Iran. They speak the Turkmen language, which is classified as a part of the Western Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages family together with Turkish, Azerbaijani, Qashqai, Gagauz and Salar.

http://wn.com/Turkmen_people -

Vardan Areveltsi

Vardan Areveltsi (; Vardan the Easterner, circa 1198 – 1271 AD) was a thirteenth century Armenian historian, geographer, philosopher and translator. In addition to establishing numerous schools and monasteries, he also left behind a rich contribution to Armenian literature. He is well known for writing Havakumn Patmutsyun (Historical Compilation ), one of the first ever attempts to write a history of the world by an Armenian historian.

http://wn.com/Vardan_Areveltsi -

World War I

World War I was a military conflict centered on Europe that began in the summer of 1914. The fighting ended in late 1918. This conflict involved all of the world's great powers, assembled in two opposing alliances: the Allies (centred around the Triple Entente) and the Central Powers. More than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, were mobilized in one of the largest wars in history. More than 9 million combatants were killed, due largely to great technological advances in firepower without corresponding ones in mobility. It was the second deadliest conflict in history.

http://wn.com/World_War_I

-

Afghanistan

{{Infobox country

http://wn.com/Afghanistan -

Agdam (rayon)

http://wn.com/Agdam_(rayon) -

Araxes River

http://wn.com/Araxes_River -

Armenia

Armenia (, transliterated : Hayastan, ), officially the Republic of Armenia (, Hayastani Hanrapetut’yun, ), is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Situated at the juncture of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, it is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia to the north, the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic and Azerbaijan to the east, and Iran and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan to the south.

http://wn.com/Armenia -

Armenian Highland

The Armenian Highland ( Haykakan leṙnašxarh; ''Armyanskoye nagor'e''; also known as the Armenian Upland, Armenian plateau, or simply Armenia) is the central-most and highest of three land-locked plateaus that together form the northern sector of the Middle East. To its west is the Anatolian plateau which rises slowly from the lowland coast of the Aegean Sea and rises to an average height of 3,000 feet. In Armenia, the average height rises dramatically to 3,000 to 7,000 feet. To its southeast is the Iranian plateau, where the elevation drops rapidly to an average 2,000 to 5,000 feet above sea level.

http://wn.com/Armenian_Highland -

Armenian Kingdom

http://wn.com/Armenian_Kingdom -

Asia Minor

http://wn.com/Asia_Minor -

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan ( ; ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan (), is one of the six independent Turkic states in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Located at the crossroads of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, it is bounded by the Caspian Sea to the east, Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west, and Iran to the south.

http://wn.com/Azerbaijan -

Azerbaijan SSR

http://wn.com/Azerbaijan_SSR -

Barda, Azerbaijan

Barda (; also, Bärdä) is the capital city of Barda Rayon, Azerbaijan. For a long period Barda was the seat of kings of Caucasian Albania and the Albanian Church, as well as an important trading and cultural centre, but it declined after the Arab invasions. During Islamic times, it was the chief city of Arran. In the tenth and eleventh centuries Barda was a metropolitan province of the Church of the East.

http://wn.com/Barda_Azerbaijan -

Caucasus

The Caucasus or Caucas (also referred to as Caucasia, , , , (''K'avk'asia''), , , , , , , ) is a geopolitical region at the border of Europe and Asia. It is home to the Caucasus Mountains, including Europe's highest mountain (Mount Elbrus).

http://wn.com/Caucasus -

Chechnya

The Chechen Republic (; , Chechenskaya Respublika; , Noxçiyn Respublika), or, informally, Chechnya (; ; , Noxçiyçö), sometimes referred to as Ichkeria, Chechnia, Chechenia or Noxçiyn, is a federal subject of Russia. It is located in southeastern part of Europe, in the Northern Caucasus mountains, in the North Caucasian Federal District. As of 1 January 2010, the population was 1,267,740 (according to Russian State statistics).

http://wn.com/Chechnya -

Dakar

Dakar is the capital city of Senegal, located on the Cap-Vert Peninsula, on the country's Atlantic coast. It is Senegal's largest city. Its position, on the western edge of Africa (it is the westernmost city on the African mainland), is an advantageous departure point for trans-Atlantic and European trade; this fact aided its growth into a major regional port.

http://wn.com/Dakar -

Dizak

Dizak (), also known as Ktish after its main stronghold, was a medieval Armenian principality in the historical Artsakh and later one of the five melikdoms of Karabakh, which included the southern third of Khachen (present-day Nagorno-Karabakh) and from the 13th century also the canton of Baghk of Syunik. The founder of this principality was Esayi abu-Muse, in the 9th century. In the 16-18th centuries Dizak was ruled by the Armenian Melik-Avanian dynasty, a branch of the House of Syunik-Khachen . The seat of the princes of Dizak was the town of Togh (or Dogh) with the adjacent ancient fortress of Ktish. One of the last princes of Dizak, Esayi Melik-Avanian, was killed by Ibrahim Khalil Khan in 1781, after a long-lasting resistance in the fortress of Ktish.

http://wn.com/Dizak -

Dushanbe

Dushanbe (, Dushanbe; Dyushambe until 1929, Stalinabad until 1961), population 679,400 people (2008 est.), is the capital and largest city of Tajikistan. Dushanbe means "Monday" in Tajik, and the name reflects the fact that the city grew on the site of a village that originally was a popular Monday marketplace.

http://wn.com/Dushanbe -

European Parliament

The European Parliament (abbreviated as Europarl or the EP) is the directly elected parliamentary institution of the European Union (EU). Together with the Council of the European Union (the Council), it forms the bicameral legislative branch of the EU and has been described as one of the most powerful legislatures in the world. The Parliament and Council form the highest legislative body within the EU. The Parliament is composed of 736 MEPs (Member of the European Parliament), who serve the second largest democratic electorate in the world (after India) and the largest trans-national democratic electorate in the world (375 million eligible voters in 2009).

http://wn.com/European_Parliament -

Georgia (country)

Georgia (, sak’art’velo ; ) is a sovereign state in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Situated at the juncture of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, it is bounded to the west by the Black Sea, to the north by Russia, to the south by Turkey and Armenia, and to the east by Azerbaijan. Georgia covers a territory of 69,700 km² and its population is more than 4.6 million. Georgia's constitution is that of a representative democracy, organized as a unitary, semi-presidential republic. It is currently a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the World Trade Organization, the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Community of Democratic Choice, the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development, and the Asian Development Bank. The country aspires to join NATO and the European Union.

http://wn.com/Georgia_(country) -

Gladzor

Gladzor (; formerly, Ortakend) is a town in the Vayots Dzor province of Armenia.

http://wn.com/Gladzor -

Haterk

http://wn.com/Haterk -

Kapan

Kapan (); former names include Ghapan, Ghap’an, Kafin, Kafan, Katan, Qafan, Zangezur, and Madan) is the capital of the Syunik province (marz) of Armenia. The city is located 316 kilometers from Yerevan

http://wn.com/Kapan -

Lesser Caucasus

Lesser Caucasus (Armenian: Փոքր Կովկաս, Azeri: Kiçik Qafqaz Dağları, Georgian: მცირე კავკასიონი, , sometimes translated as "Caucasus Minor") is one of the two main mountain ranges of Caucasus mountains, of length about 600 km.

http://wn.com/Lesser_Caucasus -

Moscow

Moscow ( or ; ; see also ) is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the world, a global city. Moscow is the most populous city on the continent of Europe and the seventh largest city proper in the world, a megacity. The population of Moscow (as of 1 January 2010) is 10,563,038.

http://wn.com/Moscow -

Murovdag

The Murovdag (or Murovdagh, ) is the highest mountain range in Lesser Caucasus (peack point - Gamish Mountain, , length ca. 70 km). It is made up mainly of Jurassic, Cretaceous and Paleogene rocks.

http://wn.com/Murovdag -

Nakhchivan

The Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic () is a landlocked exclave of Azerbaijan. The region covers 5,363 km² and borders Armenia (221 km) to the east and north, Iran (179 km) to the south and west, and Turkey (15 km) to the northwest. The capital is Nakhchivan City.

http://wn.com/Nakhchivan -

Persia

http://wn.com/Persia -

Republic of Armenia

http://wn.com/Republic_of_Armenia -

Russia

Russia (; ), also officially known as the Russian Federation (), is a state in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects. From northwest to southeast, Russia shares borders with Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (both via Kaliningrad Oblast), Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, the People's Republic of China, Mongolia, and North Korea. It also has maritime borders with Japan by the Sea of Okhotsk and the United States by the Bering Strait. At , Russia is the largest country in the world, covering more than a ninth of the Earth's land area. Russia is also the ninth most populous nation with 142 million people. It extends across the whole of northern Asia and 40% of Europe, spanning 9 time zones and incorporating a wide range of environments and landforms. Russia has the world's largest reserves of mineral and energy resources. It has the world's largest forest reserves and its lakes contain approximately one-quarter of the world's fresh water.

http://wn.com/Russia -

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg () is a city and a federal subject (a federal city) of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city's other names were Petrograd (, 1914–1924) and Leningrad (, 1924–1991). It is often called just Petersburg () and is informally known as Piter ().

http://wn.com/Saint_Petersburg -

Shusha

Shusha (), also known as Shushi () is a town in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh in the South Caucasus. It has been under the control of the self-proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh Republic since its capture in 1992 during the Nagorno-Karabakh War. However, it is a de-jure part of the Republic of Azerbaijan, with the status of an administrative division of the surrounding Shusha Rayon.

http://wn.com/Shusha -

Shusha Rayon

Shusha (Azeri: Şuşa) is a rayon of Azerbaijan. It surrounds the city of Shusha, in Nagorno-Karabakh, and is completely under control of unrecognised Nagorno-Karabakh Republic.

http://wn.com/Shusha_Rayon -

Soviet

http://wn.com/Soviet -

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, , abbreviated СССР, SSSR), informally known as the Soviet Union () or Soviet Russia, was a constitutionally socialist state that existed on the territory of most of the former Russian Empire in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991.

http://wn.com/Soviet_Union -

Stepanakert

Stepanakert (), called Khankendi () by Azerbaijan, is the largest city and capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, a de facto independent republic, though is internationally recognized as a part of Azerbaijan. The city population comprises about 53,000 ethnic Armenians.

http://wn.com/Stepanakert -

Syunik

http://wn.com/Syunik -

Syunik Province

Syunik (, also transliterated as Siunik, Siwnik, or Syunig) is the southernmost province (marz) of Armenia. It borders the Vayots Dzor marz to the north, Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan exclave to the west, Karabakh to the east, and Iran to the south. Its capital is Kapan. Other important cities and towns include Goris, Sisian, Meghri, Agarak, and Dastakert.

http://wn.com/Syunik_Province -

Tavush Province

Tavush () is a province (marz) of Armenia. It is in the north-east of the country, bordering Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to the east. Its capital is Ijevan. The province once comprised part of the northwestern region of the historic Utik province of the Kingdom of Armenia. It surrounds the Barkhudarli and Yukhari Askipara exclaves of Azerbaijan which have been controlled by Armenia since their capture during the Nagorno-Karabakh War. The other cities in Tavush are Noyemberyan, Dilijan and Berd. Berd is the center of the Shamshadin region where the late Ukrainian-Armenian painter Sarkis Ordyan was born. Tavush was part of Tiflis Governorate at first, later Elisabethpol Governorate during Russian Tsardom rule.

http://wn.com/Tavush_Province -

Turkey

Turkey (), known officially as the Republic of Turkey (), is a Eurasian country that stretches across the Anatolian peninsula in western Asia and Thrace in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe. Turkey is one of the six independent Turkic states. Turkey is bordered by eight countries: Bulgaria to the northwest; Greece to the west; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, Azerbaijan (the exclave of Nakhchivan) and Iran to the east; and Iraq and Syria to the southeast. The Mediterranean Sea and Cyprus are to the south; the Aegean Sea to the west; and the Black Sea is to the north. The Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles (which together form the Turkish Straits) demarcate the boundary between Eastern Thrace and Anatolia; they also separate Europe and Asia.

http://wn.com/Turkey -

Ukraine

Ukraine ( ; , transliterated: , ), with its area of 603,628 km2, is the second largest country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by the Russian Federation to the east and northeast, Belarus to the northwest, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary to the west, Romania and Moldova to the southwest, and the Black Sea and Sea of Azov to the south and southeast respectively.

http://wn.com/Ukraine -

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (commonly known as the United Kingdom, the UK, or Britain) is a country and sovereign state located off the northwestern coast of continental Europe. It is an island nation, spanning an archipelago including Great Britain, the northeastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller islands. Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK with a land border with another sovereign state, sharing it with the Republic of Ireland. Apart from this land border, the UK is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea, the English Channel and the Irish Sea. Great Britain is linked to continental Europe by the Channel Tunnel.

http://wn.com/United_Kingdom -

Yerevan

Yerevan (, ) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's oldest continuously-inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and industrial center of the country. It has been the capital since 1918, the thirteenth in the history of Armenia.

http://wn.com/Yerevan

- above sea level

- Adjective

- Afghanistan

- Agdam (rayon)

- Ak Koyunlu

- alpine meadow

- Amaras Monastery

- Anania Shirakatsi

- Ancient Greek

- Ancient Rome

- Arabic language

- Araxes River

- Armenia

- Armenian alphabet

- Armenian Highland

- Armenian Kingdom

- Armenian language

- Armenian SSR

- Armenians

- Artsakh

- Asia Minor

- Askeran

- Askeran clash

- Assyrian people

- Azerbaijan

- Azerbaijan SSR

- Azerbaijani language

- Azerbaijani people

- Azerbaijani SSR

- Bagrat Ulubabyan

- Ban Ki-moon

- Barda, Azerbaijan

- BBC News Online

- beech

- birchwood

- Bolshevik

- Bolsheviks

- Britannica

- Byzantium

- Caliphate

- Catholicos

- Caucasian Albania

- Caucasus

- Chechnya

- Christianity

- coal

- Communist

- Dadivank

- Dadivank Monastery

- Dakar

- Davtak Kertogh

- Dizak

- Dmitry Medvedev

- Dushanbe

- Dvin

- Eastern Armenian

- Emperor of Austria

- enclave

- Erekle II

- Estakhri

- European Parliament

- Evgeni Kirilov

- Farsi

- Galina Starovoitova

- Gandzasar Monastery

- Ganja Khanate

- Gardman

- Georgia (country)

- Getashen

- Gladzor

- gold

- Goshavank

- Greater Caucasus

- Greek people

- grenade launcher

- Gtichavank Monastery

- Hadrut

- Hasan Jalal

- Hasan Jalalyan

- Haterk

- Hayk

- Hethumids

- Heydar Aliyev

- hornbeam

- House of Khachen

- Hovhannes Imastaser

- Human Rights Watch

- hymnologist

- Ibrahim Khalil Khan

- Ilham Aliyev

- Imperial Russia

- Indigenous peoples

- Israel Ori

- Ivan Bagramyan

- Ivan Gudovich

- Ivan Isakov

- Jahan Shah

- Janapar

- Johann Schiltberger

- Joseph Emin

- Joseph Stalin

- Judaism

- Kapan

- Kara Koyunlu

- Karabakh

- Karabakh carpet

- Karabakh Khanate

- Khachen

- Khachkar

- Khojavend Rayon

- Khosrov bey Sultanov

- Kingdom of Armenia

- Kingdom of Artsakh

- Kirakos Gandzaketsi

- Kura River

- Kura-Araxes culture

- Kurds

- Kurekchay Treaty

- Lachin corridor

- landlocked

- lead

- Lesser Caucasus

- Levon Ter-Petrossian

- limestone

- Louis Figuier

- Louis XIV of France

- machine gun

- marble

- Martakert

- Martuni

- Matenadaran

- Mediterranean Sea

- melik

- Mesrob Mashtots

- Middle Ages

- Military of Russia

- mineral spring

- Mkhitar Gosh

- Moscow

- Movses Baghramian

- Movses Khorenatsi

- mujahideen

- Munich

- Murovdag

- Nader Shah

- Nagorno-Karabakh War

- nakharar

- Nakhchivan

- Napoléon Bonaparte

- Narkomnats

- oak

- Ogg

- Orontids

- OSCE

- OSCE Minsk Group

- Oshin of Lampron

- Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Turks

- PACE Resolution 1416

- Panah Ali Khan

- Paul I of Russia

- Pavel Tsitsianov

- Persia

- Persian language

- Peter the Great

- Petr Ivanovich Panin

- phonetics

- Pope Innocent XII

- power vacuum

- protectorate

- Regnum news agency

- Republic of Armenia

- RFERL

- Robert H. Hewsen

- Russia

- Russian Empire

- Russian language

- Russian people

- Safavid

- Safavid dynasty

- Sahl Smbatian

- Saint Petersburg

- Sarsang reservoir

- scriptorium

- Seljuk Turks

- Sergei Khudyakov

- Serzh Sarkisian

- Shahumian

- Shusha

- Shusha pogrom

- Shusha Rayon

- sniper

- South Caucasus

- sovereignty

- Soviet

- Soviet Union

- Sovietization

- Stepanakert

- steppe

- Strabo

- Strasbourg

- submachine gun

- Supreme Soviet

- syntax

- Syunik

- Syunik Province

- Tavush Province

- The Daily Telegraph

- The New York Times

- Tigran the Great

- Tigranakert (Silvan)

- toponym

- Transcaucasia

- Transliteration

- Treaty of Gulistan

- Trend News Agency

- Tsar

- Turkey

- Turkic language

- Turkish language

- Turkmen people

- Udis

- Ukraine

- UN General Assembly

- UNHCR

- United Kingdom

- Urartian

- Utik

- Vardan Areveltsi

- World War I

- World War II

- Yerevan

- zinc

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:00

- Published: 19 Aug 2008

- Uploaded: 12 Oct 2011

- Author: shootandscribble

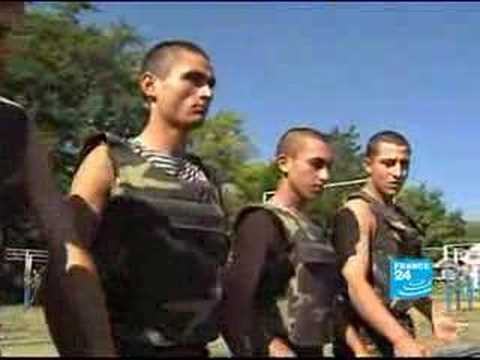

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:47

- Published: 21 Dec 2007

- Uploaded: 22 Oct 2011

- Author: france24english

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:18

- Published: 06 Oct 2011

- Uploaded: 04 Nov 2011

- Author: CaspianReport

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:34

- Published: 21 Oct 2008

- Uploaded: 05 Nov 2011

- Author: ArtsakhOnline

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:51

- Published: 03 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Oct 2011

- Author: FreeNagornoKarabakh

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:46

- Published: 28 Jun 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Oct 2011

- Author: STRATFORvideo

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 43:50

- Published: 21 Aug 2011

- Uploaded: 07 Oct 2011

- Author: RadioOdlarYurdu

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:20

- Published: 04 Nov 2011

- Uploaded: 04 Nov 2011

- Author: Californiaclip

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 12:58

- Published: 01 Oct 2011

- Uploaded: 30 Oct 2011

- Author: karabakhvideo

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:15

- Published: 03 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 22 Sep 2011

- Author: FreeNagornoKarabakh

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 17:07

- Published: 31 Aug 2007

- Uploaded: 04 Nov 2011

- Author: france24english

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:04

- Published: 02 Aug 2011

- Uploaded: 22 Sep 2011

- Author: PulitzerCenter

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 15:47

- Published: 16 May 2011

- Uploaded: 23 Oct 2011

- Author: FreeArtsakh

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:17

- Published: 03 Sep 2011

- Uploaded: 03 Sep 2011

- Author: FreeNagornoKarabakh

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:02

- Published: 14 Aug 2009

- Uploaded: 02 Nov 2011

- Author: peacemun1993

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:22

- Published: 10 Oct 2011

- Uploaded: 30 Oct 2011

- Author: ArmenianNetwork

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:42

- Published: 20 Apr 2011

- Uploaded: 02 Nov 2011

- Author: ArmeniaKharabakh

size: 12.4Kb

-

![Round breasts that project almost horizontally.There is considerable variation in a the volume, shape, size and spacing of a woman's breasts.[9] They vary in size, density, shape, Round breasts that project almost horizontally.There is considerable variation in a the volume, shape, size and spacing of a woman's breasts.[9] They vary in size, density, shape,](http://web.archive.org./web/20111108101659im_/http://cdn4.wn.com/ph/img/f8/2a/6d1a88561dfb15e6a5e27cc9f1cf-thumb.jpg) How two women's breasts were rebuilt following a mastectomy - using part of their thigh

The Daily Mail

How two women's breasts were rebuilt following a mastectomy - using part of their thigh

The Daily Mail

-

Iran, U.S. and Ethical-Religious Reasoning

WorldNews.com

Iran, U.S. and Ethical-Religious Reasoning

WorldNews.com

-

Russia warns against any military strike on Iran

The Times of India

Russia warns against any military strike on Iran

The Times of India

-

Iran's Ahmadinejad defiant as U.S. raises heat - paper

The Star

Iran's Ahmadinejad defiant as U.S. raises heat - paper

The Star

-

Islam, Wall Street and Prophetic Violence

WorldNews.com

Islam, Wall Street and Prophetic Violence

WorldNews.com

- Above mean sea level

- above sea level

- Adjective

- Afghanistan

- Agdam (rayon)

- Ak Koyunlu

- alpine meadow

- Amaras Monastery

- Anania Shirakatsi

- Ancient Greek

- Ancient Rome

- Arabic language

- Araxes River

- Armenia

- Armenian alphabet

- Armenian Highland

- Armenian Kingdom

- Armenian language

- Armenian SSR

- Armenians

- Artsakh

- Asia Minor

- Askeran

- Askeran clash

- Assyrian people

- Azerbaijan

- Azerbaijan SSR

- Azerbaijani language

- Azerbaijani people

- Azerbaijani SSR

- Bagrat Ulubabyan

- Ban Ki-moon

- Barda, Azerbaijan

- BBC News Online

- beech

- birchwood

- Bolshevik

- Bolsheviks

- Britannica

- Byzantium

- Caliphate

- Catholicos

- Caucasian Albania

- Caucasus

- Chechnya

- Christianity

- coal

- Communist

- Dadivank

- Dadivank Monastery

- Dakar

- Davtak Kertogh

- Dizak

- Dmitry Medvedev

- Dushanbe

- Dvin

- Eastern Armenian

- Emperor of Austria

- enclave

- Erekle II

size: 2.4Kb

size: 6.9Kb

size: 2.0Kb

size: 5.2Kb

size: 1.3Kb

size: 2.9Kb

size: 2.7Kb

size: 1.0Kb

size: 4.0Kb

| Native name | Լեռնային Ղարաբաղ , Leṙnayin ĠarabaġDağlıq Qarabağ / Yuxarı Qarabağ Нагорный Карабах, Nagorny Karabakh |

|---|---|

| Conventional long name | Nagorno-Karabakh |

| Common name | Nagorno-Karabakh |

| Continent | Asia |

| Region | Caucasus |

| Image map2 | Location Nagorno-Karabakh2.png |

| Map caption2 | The borders of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast |

| Area km2 | 4,400 |

| Area sq mi | 1,700 |

| Percent water | negligible |

| Population estimate | 138,000 |

| Population estimate year | 2006 |

| Population census year | 2003 |

| Population density km2 | 29 |

| Population density sq mi | 43 |

| Utc offset | +4 |

| Time zone dst | +5 |

| Drives on | right |

Most of the region is governed by the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (usually abbreviated as NKR), a de facto independent but unrecognized state established on the basis of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast of the Soviet Union's Azerbaijan SSR and populated mainly by ethnic Armenians. Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, although it has not exercised power over most of the region since 1991.

The region is usually equated with the administrative borders of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within the Azerbaijani SSR comprising an area of . The historical area of the region, however, encompasses approximately .

At present, the Constitution of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic has a territorial definition based on the total area that is under de facto control of the republic until a future settlement of the conflict, plus territories lost to Azerbaijan during the war. This area includes the district of Shahumian and the rural community of Getashen, which NKR does not control at the moment, as well as some territories of Azerbaijan that NKR presently controls. The latter, often referred to as the Nagorno-Karabakh buffer zone, link the Nagorno Karabakh Republic and Armenia.

Etymology

The original, historical and most enduring name for Nagorno-Karabakh is Artsakh (Armenian: ), which is used mostly by Armenians and designates the 10th province of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia. As a political and geographical term Artsakh was used continuously throughout the Middle Ages and modern times. In Urartian inscriptions (9th–7th centuries BC), the name Urtekhini is used for the region. Ancient Greek sources called the area Orkhistene. Both Urtekhini and Orkhistene are thought to be phonetic variants of the word Artsakh. In the high Middle Ages, the entire region was often called Khachen, after the name of Artsakh's largest and most politically significant district. The name “Khachen” originated from Armenian word khach which means “cross”.Other names used to denote Nagorno Karabakh in history include: Lesser Armenia, Lesser Syunik, and Armenia Interior.

, founded in Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1st century BC by Tigran the Great, King of Armenia (95–55 BC), is the oldest historical monument in the region with which the toponym Artsakh has been associated. Tigran the Great built four cities named Tigranakert in different parts of the Kingdom of Armenia.]]

The term Nagorno-Karabakh is a modern construct. The word Nagorno- is a Russian attributive adjective, derived from the adjective nagorny (нагорный), which means "highland". The Azerbaijani name of the region includes similar adjectives "dağlıq" (mountainous) or "yuxarı" (upper). Such words are not used in Armenian name, but appeared in the official name of the region during the Soviet era as Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. Other languages apply their own wording for mountainous, upper, or highland; for example, the official name used by the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic in France is Haut-Karabakh, meaning "Upper Karabakh".

The word Karabakh is generally held to originate from Turkic and Persian, and literally means "black garden". The name first appears in Georgian and Persian sources of the 13th and 14th centuries. Karabagh is an acceptable alternate spelling of Karabakh, and also denotes a kind of patterned rug originally produced in the area.

In an alternative theory proposed by Bagrat Ulubabyan the name Karabakh has a Turkic-Armenian origin, meaning "Greater Baghk" (), a reference to Ktish-Baghk (later: Dizak), one of the principalities of Artsakh under the rule of the Aranshahik dynasty, which held the throne of the Kingdom of Syunik in the 11th–13th centuries and called itself the "Kingdom of Baghk".]] was commissioned by the House of Khachen and completed in 1238]] , built by the Karabakh Khanate ruler Panah Ali Khan in the 18th century]] (Kingdom of Artsakh) during the reign of Grand Prince Hasan Jalal Vahtangian (1214-1261), featuring Armenian Christian abbreviations - Lord, God, Jesus, and Christ.]] :ru:Ованес III Одзнеци. Source: Բաբկեն ՀԱՐՈՒԹՅՈՒՆՅԱՆ. ՍԲ ՀՈՎՀԱՆՆԵՍ Գ ՕՁՆԵՑԻ. Հայկական Հանրագիտարան. 1977.]] Nagorno-Karabakh falls within the lands occupied by peoples known to modern archaeologists as the Kura-Araxes culture, who lived between the two rivers Kura and Araxes.

It is thought that the original population of the region consisted of various autochthonous and migrant tribes. According to the American scholar Robert H. Hewsen, these primordial tribes were "certainly not of Armenian origin", and "although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans".

However, relying on information provided by the 5th century Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, other Western authors argued—and Hewsen himself indicated later—that these peoples could have been added to the Kingdom of Armenia much earlier, in the 4th century BC.

Overall, from around 180 BC and up until the 4th century AD — before becoming part of the Armenian Kingdom again, in 855 — the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh remained part of the united Armenian Kingdom as the province of Artsakh.

Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since Roman times: Strabo states that, by the second or first century BC, the entire population of Greater Armenia—Artsakh and Utik included—spoke Armenian, though this does not mean that its population consisted exclusively of ethnic Armenians.

Tigran the Great, King of Armenia, (ruled 95–55 BC), founded in Artsakh one of four cities named “Tigranakert” after himself. The ruins of the ancient Tigranakert, located 30 miles north-east of Stepanakert, are being studied by a group of international scholars.

After the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia, in 387 AD, Artsakh became part of Caucasian Albania, which, in turn, came under strong Armenian religious and cultural influence. The Armenian medieval atlas Ashkharatsuits (Աշխարացույց), compiled in the 7th century by Anania Shirakatsi (Անանիա Շիրակացի, but sometimes attributed to Movses Khorenatsi as well), categorizes Artsakh and Utik as provinces of Armenia despite their presumed detachment from the Armenian Kingdom and their political association with Caucasian Albania and Persia at the time of his writing. Shirakatsi specifies that Artsakh and Utik are “now detached” from Armenia and included in “Aghvank,” and he takes care to distinguish this new entity from the old “Aghvank strictly speaking” (Բուն Աղվանք) situated north of the river Kura. Because the Armenian element was more homogeneous and more developed than the tribes living to the north of the Kura River, Armenians took over Caucasian Albania’s political life and was progressively able to impose its language and culture.

Whatever little is known about Nagorno-Karabakh and other eastern Armenian-peopled territories in the early Middle Ages comes from the text History of the Land of Aghvank (Պատմություն Աղվանից Աշխարհի) attributed to two Armenian authors: Movses Kaghankatvatsi and Movses Daskhurantsi. This text, written in Old Armenian, in essence represents the history of Armenia’s provinces of Artsakh and Utik. Kaghankatvatsi, repeating Movses Khorenatsi, mentions that the very name “Aghvank”/“Albania” is of Armenian origin, and relates it to the Armenian word “aghu” (աղու, meaning “kind,” “benevolent”. Khorenatsi states that “aghu” was a nickname given to Prince Arran, whom the Armenian king Vagharshak I appointed as governor of northeastern provinces bordering on Armenia. According to a legendary tradition reported by Khorenatsi, Arran was a descendant of Sisak, the ancestor of the Siunids of Armenia’s province of Syunik, and thus a great-grandson of the ancestral eponym of the Armenians, the Forefather Hayk. Kaghankatvatsi and another Armenian author, Kirakos Gandzaketsi, confirm Arran’s belonging to Hayk’s blood line by calling Arranshahiks “a Haykazian dynasty.”

By the early Middle Ages, the non-Armenian elements of Caucasian Albanian population of upper Karabakh had completed their merger into the Armenian population, and forever disappeared as identifiable groups.

Armenian culture and civilization flourished in the early medieval Nagorno-Karabakh — in Artsakh and Utik. In the 5th century, the first-ever Armenian school was opened on the territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh — at the Amaras Monastery— by the efforts of St. Mesrob Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian Alphabet. St. Mesrob was very active in preaching Gospel in Artsakh and Utik. Four chapters of Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s “History...” amply describe St. Mesrob’s mission, referring to him as “enlightener,” “evangelizer” and “saint”. Overall, Mesrob Mashtots made three trips to Artsakh and Utik, ultimately reaching pagan territories at the foothills of the Greater Caucasus. It was at that time when the foremost Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi confirmed that the Kura River formed "the boundary of Armenian speech." The 7th-century Armenian linguist and grammarian Stephanos Syunetsi stated in his work that Armenians of Artsakh had their own dialect, and encouraged his readers to learn it. The same advice to study the Armenian dialect of Artsakh was repeated by Essayi Nchetsi in the 14th century, the founder of the University of Gladzor. In the same 7th century, Armenian poet Davtak Kertogh writes his Elegy on the Death of Grand Prince Juansher, where each passage begins with a letter of Armenian script in alphabetical order.

In the 5th century’s Nagorno Karabakh Vachagan II the Pious, ruler of Aghvank, adopted the so-called Constitution of Aghven (Սահմանք Կանոնական) — a code of civil regulations consisting of 21 articles and composed after a series of talks with leading clerical and civil figures of Armenia and Aghvank (e.g. Bishop of Syunik). In the 8th century, the Constitution of Aghven was included in the Armenian Book of Laws (Կանոնագիրք Հայոց) by the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church Hovhan III Odznetsi (Catholicos from 717-728), thus laying out a blueprint for later-era Armenian legal texts, such as the Lawcode written in the 12th century by Mkhitar Gosh. The Constitution of Aghven usually features as an inclusion in Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s History of the Land of Aghvank.

High Middle Ages

inside Gandzasar Monastery (1216-1238).]] (1130–1213), author of the Lawcode. Statute in front of the Matenadaran institute in Yerevan, Armenia.]] In the 7th and 8th centuries, during the Arab conquest of the Caucasus, the region was ruled by Caliphate-appointed local governors selected among local dynasts. In 821 the Armenian prince Sahl Smbatian revolted in Artsakh and established the House of Khachen, which ruled parts of Artsakh as a principality until the early 19th century. The name “Khachen” originated from Armenian word “khach,” which means “cross”. Initially, the province of Dizak, in southern part of modern Nagorno-Karabakh, also formed a kingdom ruled by the ancient House of Aranshahik, which descended from the region's earliest monarchs.After the invasion of the Caucasus and Asia Minor by Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, some Armenian noble families from Artsakh chose to flee westward to the province of Cilicia on the Mediterranean Sea, joining their fellow countrymen from other provinces of Armenia. Among them was Oshin of Lampron, Lord of Parisos, who left Artsakh in 1071 and established the Hethumian dynasty that ruled the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in the 13th and 14th centuries.

In 1216, when the daughter of Dizak's last king, Mamkan, married Hasan Jalal Dola, the king of Artsakh, Dizak and Khachen merged into one, which expanded of the territory of the Kingdom of Artsakh further still. After the death of Hasan Jalal Dola, Artsakh continued to exist as a principality.

The strengthening of the Kingdom of Artsakh brought about an unprecedented surge of Armenian cultural and political activity in medieval Nagorno Karabakh and neighboring territories that were under the influence of the kingdom. All major ecclesiastical monuments in the region were constructed or rebuilt in that timeframe, including the Gandzasar Monastery, Gtichavank Monastery, and Dadivank Monastery. The scholar, poet and hymnologist Hovhannes Imastaser (c. 1047-1129), a native of the northern district of Gardman of medieval Nagorno Karabakh, wrote his main works on philosophy, science and literature and composed sharakans and taghs (hymns), such as Ode of the Resurrection . Historian and geographer Vardan Areveltsi (c. 1198–1271) completed his Historical Compilation ( Հաւաքումն պատմութեան), the first history of the world in Armenian. The legal scholar Mkhitar Gosh (1130–1213) wrote his Law Code ( Կանոնագիրք), under the patronage of Prince Hasan the Monk of Khachen, who also sponsored the construction of the monastery at Nor Getik, which received the name Goshavank after Gosh. The major historian Kirakos Gandzaketsi (c. 1200–1271), wrote his History of Armenia.

Nagorno Karabakh’s Gandzasar Monastery during the reign of Grand Prince Hasan Jalal Vahtangian (1214–1238) became home to Armenia's first completed Haysmavurk (Synaxarion in Greek; : Հայսմավուրկ; also known as the “Book of Saints”), a calendar collection of short lives of saints and accounts of important religious events. The idea to have a new, better organized Haysmavurk came from Hasan Jalal himself, who then placed his request with Father Israel (Ter-Israel; Տեր-Իսրաել), a disciple of an important Armenian medieval philosopher and Artsakh native known as Vanakan Vardapet. The Haysmavurk was further developed by Kirakos Gandzaketsi. Ever since, the Haysmavurk ordered by Hasan Jalal became known as "Synaxarion of Ter-Israel;" it was mass printed in Constantinople in 1834. The Gandzasar Monastery as well as Dadivank also hosted important scriptoria, which produced important illuminated manuscripts, such as the world-renowned Red Gospel of Gandzasar (1232). The Red Gospel is on display at the University of Chicago’s library (USA) and belongs to the Goodspeed Manuscript Collection. (prince) David Melik-Shahnazarian of Nagorno Karabakh, Napoléon Bonaparte's envoy to Persia.]] These five Armenian principalities (melikdoms) in Karabakh were as following:

The principalities of Nagorno Karabakh considered themselves direct descendants of the Kingdom of Armenia, and were recognized as such by foreign powers

In the early 16th century, after the fall of the Ak Koyunlu state, control of the region passed to the Safavid dynasty, which created the Karabakh Beylerbeylik. Despite these conquests, the population of Upper Karabakh remained largely Armenian. Initially under the control of the Ganja Khanate of the Persian Empire, wide autonomy of local Armenian princes over the territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent lands was confirmed by the Safavid Empire over.

The Armenian meliks maintained full control over the region until the mid-18th century. In the early 18th century, Persia's Nader Shah took Karabakh out of control of the Ganja khans in punishment for their support of the Safavids, and placed it under his own control At the same time, the Armenian meliks were granted supreme command over neighboring Armenian principalities and Muslim khans in the Caucasus, in return for the meliks' victories over the invading Ottoman Turks in the 1720s.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Nagorno Karabakh became an epicenter of the rebirth of the idea of Armenian independence. This state, centered on semi-independent Armenian principalities of Artsakh and Syunik, would be allied with Georgia and protected by Russia. Another prominent patriot from Nagorno Karabakh who worked to establish an independent Armenian entity in his homeland was Movses Baghramian. Baghramian accompanied the Armenian patriot Joseph Emin (1726–1809), and tried to secure the help of Karabakh's Armenian meliks.

In the mid-18th century, as internal conflicts between the meliks led to their weakening, the Karabakh khanate was formed.

Karabakh became a protectorate of the Imperial Russia by the Kurekchay Treaty, signed between Ibrahim Khalil Khan of Karabakh and general Pavel Tsitsianov on behalf of Tsar Alexander I in 1805, according to which the Russian monarch recognized Ibrahim Khalil Khan and his descendants as the sole hereditary rulers of the region. Its new status was confirmed under the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan (1823), when Persia formally ceded Karabakh to the Russian Empire, before the rest of Transcaucasia was incorporated into the Empire in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmenchay.

In 1822, the Karabakh khanate was dissolved, and the area became part of the Elisabethpol Governorate within the Russian Empire. After the transfer of the Karabakh khanate to Russia, many Muslim families emigrated to Persia, while many Armenians were induced by the Russian government to emigrate from Persia to Karabakh.

Russian Revolution, Civil War and Soviet era (1917-1991)

after the city's destruction by Azerbaijani army in March 1920. In the center: defaced Armenian cathedral of the Holy Savior]] dedicated to the region's legendary long-livers]] 's secession from Azerbaijani SSR]] The present-day conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has its roots in the decisions made by Joseph Stalin and the Caucasian Bureau () during the Sovietization of Transcaucasia. Stalin was the acting Commissar of Nationalities for the Soviet Union during the early 1920s, the branch of the government under which the Kavburo was created. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Karabakh became part of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, but this soon dissolved into separate Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian states. Over the next two years (1918–20), there were a series of short wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan over several regions, including Karabakh. In July 1918, the First Armenian Assembly of Nagorno-Karabakh declared the region self-governing and created a National Council and government. Later, Ottoman troops entered Karabakh, meeting armed resistance by Armenians.After the defeat of Ottoman Empire in World War I, British troops occupied Karabakh. The British command provisionally affirmed Khosrov bey Sultanov (appointed by the Azerbaijani government) as the governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur, pending final decision by the Paris Peace Conference. The decision was opposed by Karabakh Armenians. In February 1920, the Karabakh National Council preliminarily agreed to Azerbaijani jurisdiction, while Armenians elsewhere in Karabakh continued guerrilla fighting, never accepting the agreement. The agreement itself was soon annulled by the Ninth Karabagh Assembly, which declared union with Armenia in April.

In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by Bolsheviks. On August 10, 1920, Armenia signed a preliminary agreement with the Bolsheviks, agreeing to a temporary Bolshevik occupation of these areas until final settlement would be reached. In 1921, Armenia and Georgia were also taken over by the Bolsheviks who, in order to attract public support, promised they would allot Karabakh to Armenia, along with Nakhchivan and Zangezur (the strip of land separating Nakhchivan from Azerbaijan proper). However, the Soviet Union also had far-reaching plans concerning Turkey, hoping that it would, with a little help from them, develop along Communist lines. Needing to placate Turkey, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. Had Turkey not been an issue, Stalin would likely have left Karabakh under Armenian control. As a result, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was established within the Azerbaijan SSR on July 7, 1923.

With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged. Accusing the Azerbaijani SSR government of conducting forced azerification of the region, the majority Armenian population, with ideological and material support from the Armenian SSR, started a movement to have the autonomous oblast transferred to the Armenian SSR. The oblast's borders were drawn to include Armenian villages and to exclude as much as possible Azerbaijani villages. The resulting district ensured an Armenian majority.

Secession, War and Nagorno Karabakh Republic

, knocked out of commission while attacking Azeri positions in Askeran, serves as a war memorial on the outskirts of Stepanakert.]] Suddenly, and unexpectedly, on February 13, 1988, Karabakh Armenians began demonstrating in their capital, Stepanakert, in favour of unification with the Armenian republic. Six days later they were joined by mass marches in Yerevan. On February 20 the Soviet of People's Deputies in Karabakh voted 110 to 17 to request the transfer of the region to Armenia. This unprecedented action by a regional soviet brought out tens of thousands of demonstrations both in Stepanakert and Yerevan, but Moscow rejected the Armenians' demands. On February 22, 1988, the first direct confrontation of the conflict occurred as a large group of Azeris marched from Agdam against the Armenian populated town of Askeran, "wreaking destruction en route." The confrontation between the Azeris and the police near Askeran degenerated into the Askeran clash, which left two Azeris dead, one of them reportedly killed by an Azeri police officer, as well as 50 Armenian villagers, and an unknown number of Azerbaijanis and police, injured. Large numbers of refugees left Armenia and Azerbaijan as violence began against the minority populations of the respective countries. In the fall of 1989, intensified inter-ethnic conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh led the Soviet Union to grant Azerbaijani authorities greater leeway in controlling the region. On November 29, 1989 direct rule in Nagorno-Karabakh was ended and the region was returned to Azerbaijani administration. The Soviet policy backfired, however, when a joint session of the Armenian Supreme Soviet and the National Council, the legislative body of Nagorno-Karabakh, proclaimed the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. In 1989, Nagorno-Karabakh had a population of 192,000. The population at that time was 76% Armenian and 23% Azerbaijanis, with Russian and Kurdish minorities.On December 10, 1991 in a referendum boycotted by local Azerbaijanis, Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh approved the creation of an independent state. A Soviet proposal for enhanced autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan satisfied neither side, and a full-scale war subsequently erupted between Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, the latter receiving support from Armenia. According to Armenia's former president, Levon Ter-Petrossian, the Karabakh leadership approach was maximalist and “they thought they could get more.”

The struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh escalated after both Armenia and Azerbaijan attained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. In the post-Soviet power vacuum, military action between Azerbaijan and Armenia was heavily influenced by the Russian military. Furthermore, both the Armenian and Azerbaijani military employed a large number of mercenaries from Ukraine and Russia. As many as one thousand Afghan mujahideen participated in the fighting on Azerbaijan's side. There were also fighters from Chechnya fighting on the side of Azerbaijan. Many survivors from the Azerbaijani side found shelter in 12 emergency camps set up in other parts of Azerbaijan to cope with the growing number of internally displaced people due to the Nagorno-Karabakh war.

By the end of 1993, the conflict had caused thousands of casualties and created hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. By May 1994, the Armenians were in control of 14% of the territory of Azerbaijan. At that stage, for the first time during the conflict, the Azerbaijani government recognized Nagorno-Karabakh as a third party in the war, and started direct negotiations with the Karabakh authorities. As a result, a cease-fire was reached on May 12, 1994 through Russian negotiation.

Contemporary situation (since 1994)

. Armenian forces of Nagorno-Karabakh currently control almost 9% of Azerbaijan's territory outside the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast., while Azerbaijani forces control Shahumian and the eastern parts of Martakert and Martuni.]] with Ilham Aliyev and Serzh Sarkisian in Moscow on 2 November 2008]] , Nagorno Karabakh Republic]] Despite the ceasefire, fatalities due to armed conflicts between Armenian and Azerbaijani soldiers continued. On January 25, 2005 PACE adopted Resolution 1416, which condemns the use of ethnic cleansing against the Azerbaijani population, and supporting the occupation of Azerbaijani territory. On 15–17 May 2007 the 34th session of the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference adopted resolution № 7/34-P, considering the occupation of Azerbaijani territory as the aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan and recognizing the actions against Azerbaijani civilians as a crime against humanity, and condemns the destruction of archaeological, cultural and religious monuments in the occupied territories.At the 11th session of the summit of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference held on March 13–14, 2008 in Dakar, resolution № 10/11-P (IS) was adopted. According to the resolution, OIC member states condemned the occupation of Azerbaijani lands by Armenian forces and Armenian aggression against Azerbaijan, alleged ethnic cleansing against the Azeri population, and charged Armenia with the "destruction of cultural monuments in the occupied Azerbaijani territories." On March 14 of the same year the UN General Assembly adopted non-binding Resolution № 62/243 which "demands the immediate, complete and unconditional withdrawal of all Armenian forces from all occupied territories of the Republic of Azerbaijan". In August 2008, the United States, France, and Russia (the co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group) were mediating efforts to negotiate a full settlement of the conflict, proposing a "a referendum or a plebiscite, at a time to be determined later," to determine the final status of the area, return for some territories under Karabakh's control, and security guarantees. Ilham Aliyev and Serzh Sarkisian traveled to Moscow for talks with Dmitry Medvedev on 2 November 2008. The talks ended in the three Presidents signing a declaration confirming their commitment to continue talks. The two presidents have met again since then, most recently in Saint Petersburg.

On November 22, 2009, several world leaders, among them the heads of state from Azerbaijan and Armenia, met in Munich in the hopes of renewing efforts to reach a peaceful settlement on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Prior to the meeting, President Aliyev once more threatened to resort to military force to reestablish control over the region if the two sides did not reach an agreeable settlement at the summit.

On February 18, 2010 three Azerbaijani soldiers were killed and one wounded as a result of the ceasefire violation in that year. On November 20 of the same year an Armenian sniper opened fire on Azerbaijani positions in Khojavend Rayon, killing one Azerbaijani soldier. This incident brought the number of soldiers killed from both sides in August—November, 2010 to twelve. On September 25, 2010 the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon supported the withdrawal of snipers from the contact line. The spokesman of Azerbaijani Defence Ministry Lt-Col Eldar Sabiroglu, however, commented that Armenian servicemen used to fire on opposite positions across the contact line from machine- and submachine guns, as well as from grenade launchers, and that these weapons have even been used against civilians. On May 18–20, 2010 at the 37th session of the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Organisation of Islamic Conference in Dushanbe, another resolution condemning the aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan, recognizing the actions against Azerbaijani civilians as a crime against humanity and condemning the destruction of archaeological, cultural and religious monuments in occupied territories was adopted. On May 20 of the same year the European Parliament in Strasbourg adopted the resolution on "The need for an EU Strategy for the South Caucasus" on the basis of the report by Evgeni Kirilov, Bulgarian member of the Parliament. The resolution states in particular that "the occupied Azerbaijani regions around Nagorno-Karabakh must be cleared as soon as possible".

Russia, in conjunction with France and the United States, convened talks in June 2011 with the hope that pressure applied to the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan could lead to an agreement over the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh. But no resolution of the dispute over the enclave was achieved.

Geography

.]] Nagorno-Karabakh, considered within the Soviet-era borders of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, had a total area of 4,400 square kilometers (1,699 sq mi) and was an enclave surrounded entirely by Azerbaijani SSR; its nearest point to Armenian SSR was across the present-day Lachin corridor, roughly 4 kilometers across. Approximately half of Nagorno-Karabakh terrain is over 950 m above sea level. The Soviet-era borders of Nagorno-Karabakh resembled a kidney bean with the indentation on the east side. It has tall mountain ridges along the northern edge and along the west and a mountainous south. The part near the indentation of the kidney bean itself is a relatively flat valley, with the two edges of the bean, the provinces of Martakert and Martuni, having flat lands as well. Other flatter valleys exist around the Sarsang reservoir, Hadrut, and the south. The entire region lies, on average, above sea level. Notable peacks include the border mountain Murovdag and the Great Kirs mountain chain in the junction of Shusha Rayon and Hadrut. The territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh forms a portion of historical regions of Artsakh and Karabakh, which lie between the rivers Kura and Araxes, and the modern Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Nagorno-Karabakh in its modern borders is part of the larger region of Upper Karabakh.Nagorno-Karabakh’s environment vary from steppe on the Kura lowland through dense forests of oak, hornbeam and beech on the lower mountain slopes to birchwood and alpine meadows higher up. The region possesses numerous mineral springs and deposits of zinc, coal, lead, gold, marble and limestone. The major cities of the region are Stepanakert, which serves as the capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, and Shusha, which lies partially in ruins. Vineyards, orchards and mulberry groves for silkworms are developed in the valleys.

Culture of Nagorno-Karabakh

Language

The majority of the population in Nagorno-Karabakh speaks an ancient Artsakh dialect of Eastern Armenian, which was first described in the 7th century by the grammarian and philosopher Stephanos Syunetsi. The continued existence of this dialect was noted in the writings of Yessayi Nchetsi, a 14th century author and founder of Armenia’s University of Gladzor. Due to its unique phonetics and archaic syntax developed in relative isolation from other Armenian vernaculars, the Artsakh dialect is not entirely intelligible by other Armenian speakers.

Demographics and ethnic composition

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

codifying military draft obligations of Armenian nakharar dynasties before the King. According to Zoranamak, provinces of Artsakh and Utik were responsible for providing 3000 soldiers.]] Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since Roman times: Strabo states that, by the second or first century BC, the entire population of Greater Armenia—Artsakh and Utik included—spoke Armenian,The Armenian population of Artsakh and Utik remained in place after the partition of the Kingdom of Armenia in 387, as did the entire political, social, cultural and military structure of the provinces.

The population of Nagorno Karabakh was Armenian throughout the Middle Ages. In his description about the Caucasus and neighboring regions, Iranian geographer Abu Ishaq al Istakhri noted in his 10th century work Book of Climates that the road from Bardaa to Dabil lies through the lands of Armenians that belong to Sunbat, son of Ashut, i.e. to Sahl Smbatian, Prince of Khachen, and that "population of Khachen is Armenian."

Johann Schiltberger (1380–c. 1440), a German traveler and writer, observed in the beginning of the 15th century that Karabakh's lowlands divided by the Kura River are populated by Armenians and mentioned Karabakh as part of Armenia.

Late Middle Ages

Concrete numbers about the demographic situation in Nagorno-Karabakh appear since the 18th century. Archimandrite Minas Tigranian, after completing his secret mission to Persian Armenia ordered by the Russian Tsar Peter the Great stated in a report dated March 14, 1717 that the patriarch of the Gandzasar Monastery, in Nagorno-Karabakh, had under his authority 900 Armenian villages. Nagorno-Karabakh's Armenian military commander Tarkhan suggests in his letter to Russia's Collegium of Foreign Affairs dated October 1729 that the four military districts of his land - the seghnakhs - had 30,000 Armenian soldiers, in addition to merchants and other civilians.In his letter of 1769 to Russia’s Count P. Panin, the Georgian king Erekle II, in his description of Nagorno-Karabakh, suggests: "Seven families rule the region of Khamse. Its population is totally Armenian."

When discussing Karabakh and Shusha in the 18th century, the Russian diplomat and historian S. M. Bronevskiy (Russian: С. М. Броневский) indicated in his Historical Notes that Karabakh, which he said "is located in Greater Armenia" had as many as 30–40,000 armed Armenian men in 1796.

Close to 30,000 Armenians left Nagorno-Karabakh in the late 18th century as a result of famine and persecution of Armenian nobility by the Karabakh khan. In 1797, Russian Tsar Paul I of Russia in his letter to General Ivan Gudovich mentioned that the number of Armenians who had to flee Nagorno-Karabakh for Georgia was close to 11,000 families.

Russian Rule (1805-1918)

A survey prepared by the Russian imperial authorities in 1823, several years before the 1828 Armenian migration from Persia to the newly established Armenian Province, shows that all Armenians of Karabakh (5107 boroughs) compactly resided in its highland portion, i.e. on the territory of the five traditional Armenian principalities in Nagorno-Karabakh, and constituted an absolute demographic majority on those lands. The survey's more than 260 pages recorded that the district of Khachen had twelve Armenian villages and no Tatar (Muslim) villages; Jalapert (Jraberd) had eight Armenian villages and no Tatar villages; Dizak had fourteen Armenian villages and one Tatar village; Gulistan had twelve Armenian and five Tatar villages; and Varanda had twenty-three Armenian villages and one Tatar village.According to a Russian census, in 1897 there were 106,363 Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh, and they made up 94 percent of the rural population within the boundaries of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.

and Nagorno-Karabakh Republic in 1921-1989, and 2007]]

Soviet Era

In the Soviet times, Azerbaijan tried to change demographic balance in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region (NKAO) in favor of Azerbaijanis and to the detriment of its Armenian majority by sending Azerbaijanis from other parts of Azerbaijani SSR to NKAO. In 2002, Azerbaijan’s President Heydar Aliyev made a public confession that he personally conceived and directed a policy of squeezing out Armenians from the province and replacing them with Azerbaijanis. Adding an Azerbaijani sector to a local university and sending Azerbaijani workers to a newly-commissioned shoe factory were mentioned by Heydar Aliyev among the tools of his demographic policy.Anon. "Кто на стыке интересов? США, Россия и новая реальность на границе с Ираном" ("Who is at the turn of interests? US, Russia and new reality on the border with Iran"). Regnum. April 4, 2006}}

Heydar Aliyev's commentary was supported by his colleagues and subordinates, such as Ramil Usubov - Azerbaijan's long-served Minister of the Interior.

Nearing the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast boasted a population of 145,593 Armenians (76.4%), 42,871 Azerbaijanis (22.4%), and several thousand Kurds, Russians, Greeks, and Assyrians. Most of the Azerbaijani and Kurdish populations fled the region during the heaviest years of fighting in the war from 1992 to 1993. The main language spoken in Nagorno-Karabakh is Armenian; however, Karabakh Armenians speak a dialect of Armenian which is considerably different from that which is spoken in Armenia as it is layered with Russian, Turkish and Persian words.

Nagorno-Karabakh Republic