| Cream |

Cream, 1966. L-R: Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce, and Eric Clapton |

| Background information |

| Origin |

London, England |

| Genres |

Psychedelic rock, blues rock, hard rock, acid rock |

| Years active |

1966 (1966)–1968, 1993, 2005 |

| Labels |

Reaction, Polydor, Atco, RSO, Reprise |

| Associated acts |

Powerhouse, The Graham Bond Organisation, John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, Blind Faith, Bruce-Baker-Moore |

| Past members |

Jack Bruce

Eric Clapton

Ginger Baker |

Cream were a 1960s British rock supergroup consisting of bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce, guitarist/vocalist Eric Clapton, and drummer Ginger Baker. Their sound was characterised by a hybrid of blues rock, hard rock and psychedelic rock,[1] combining the psychedelia-themed lyrics, Eric Clapton's blues guitar playing, Jack Bruce's voice and prominent bass playing and Ginger Baker's jazz-influenced drumming. The group's third album, Wheels of Fire, was the world's first platinum-selling double album.[2][3] Cream are widely regarded as being the world's first successful supergroup.[4][5][6][7] In their career, they sold over 15 million albums worldwide.[8]

Cream's music included songs based on traditional blues such as "Crossroads" and "Spoonful", and modern blues such as "Born Under a Bad Sign", as well as more eccentric songs such as "Strange Brew", "Tales of Brave Ulysses" and "Toad". Cream's biggest hits were "I Feel Free" (UK, number 11),[3] "Sunshine of Your Love" (US, number 5),[9] "White Room" (US, number 6),[9] "Crossroads" (US, number 28),[9] and "Badge" (UK, number 18).[10]

Cream made a significant impact on the popular music of the time, and, along with Jimi Hendrix, popularised the use of the wah-wah pedal. They provided a heavy yet technically proficient musical theme that foreshadowed and influenced the emergence of British bands such as Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, and The Jeff Beck Group in the late 1960s. The band's live performances influenced progressive rock acts such as Rush,[11] jam bands such as The Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead, Phish and heavy metal bands such as Black Sabbath.[12]

Cream were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.[13] They were included in both Rolling Stone and VH1's lists of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".[14][15] They were also ranked number 16 on VH1's "100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock".[16]

By July 1966, Eric Clapton's career with The Yardbirds and John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers had earned him a reputation as the premier blues guitarist in Britain.[1] Clapton, however, found the environment of Mayall's band confining, and sought to expand his playing in a new band.

In 1966, Clapton met Ginger Baker, then the leader of the Graham Bond Organisation, which at one point featured Jack Bruce on bass guitar, harmonica and piano. Baker felt stifled in the Graham Bond Organisation and had grown tired of Graham Bond's drug addictions and bouts of mental instability. "I had always liked Ginger", explained Clapton. "Ginger had come to see me play with the Bluesbreakers. After the gig he drove me back to London in his Rover. I was very impressed with his car and driving. He was telling me that he wanted to start a band, and I had been thinking about it too."[17] Each was impressed with the other's playing abilities, prompting Baker to ask Clapton to join his new, then-unnamed group. Clapton immediately agreed, on the condition that Baker hire Bruce as the group's bassist;[3] according to Clapton, Baker was so surprised at the suggestion that he almost crashed the car.[18]

Clapton had met Bruce when the bassist/vocalist briefly played with the Bluesbreakers in March 1966;[3] the two also had worked together as part of a one-shot band called Powerhouse (which also included Steve Winwood and Paul Jones). Impressed with Bruce's vocals and technical prowess, Clapton wanted to work with him on an ongoing basis.

In contrast, while Bruce was in Bond's band, he and Baker had been notorious for their quarreling.[19] Their volatile relationship included on-stage fights and the sabotage of one another's instruments.[19] After Baker fired Bruce from the band, Bruce continued to arrive for gigs; ultimately, Bruce was driven away from the band after Baker threatened him at knifepoint.[citation needed]

Baker and Bruce put aside their differences for the good of Baker's new trio, which he envisioned as collaborative, with each of the members contributing to music and lyrics. The band was named "Cream", as Clapton, Bruce, and Baker were already considered the "cream of the crop" amongst blues and jazz musicians in the exploding British music scene. Before deciding upon "Cream", the band considered calling themselves "Sweet 'n' Sour Rock 'n' Roll". Of the trio, Clapton had the biggest reputation in England; however, he was all but unknown in the United States, having left The Yardbirds before "For Your Love" hit the American Top Ten.[1]

Cream made its unofficial debut at the Twisted Wheel on 29 July 1966.[3][20] Its official debut came two nights later at the Sixth Annual Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival.[3][20] Being new and with few original songs to its credit, Cream performed blues reworkings that thrilled the large crowd and earned it a warm reception. In October the band also got a chance to jam with Jimi Hendrix, who had recently arrived in London. Hendrix was a fan of Clapton's music, and wanted a chance to play with him onstage.[3] Hendrix was introduced to Cream through Chas Chandler, Hendrix's manager.[3]

It was during the early organisation that they decided Bruce would serve as the group's lead vocalist. While Clapton was shy about singing,[21] he occasionally harmonised with Bruce and, in time, took lead vocals on some Cream tunes including "Four Until Late",[22] "Strange Brew",[23] "World of Pain",[24] "Outside Woman Blues",[23] "Anyone for Tennis",[25] "Crossroads",[26] and "Badge".[27]

[edit] Fresh Cream

Cream's debut album, Fresh Cream, was recorded and released in 1966. The album reached number 6 in the UK charts and number 39 in the United States.[28] It was evenly split between self-penned originals and blues covers, including "Four Until Late", "Rollin' and Tumblin'", "Spoonful", "I'm So Glad"[7] and "Cat's Squirrel". The rest of the songs were written by either Jack Bruce or Ginger Baker. "I Feel Free", a UK hit single,[3] was only included on the American edition of the LP). The track "Toad" contained one of the earliest examples of a drum solo in rock music.

The early Cream bootlegs display a much tighter band showcasing more songs. All of the songs are reasonably short five-minute versions of "N.S.U.", "Sweet Wine" and "Toad". But a mere two months later, the setlist shortened, with the songs then much longer.

[edit] Disraeli Gears

Cream first visited the United States in March 1967 to play nine dates at the RKO Theater in New York. They returned to record Disraeli Gears in New York between 11 May and 15 May 1967.[29] Cream's second album was released in November 1967 and reached the Top 5 in the charts on both sides of the Atlantic.[30] Produced by Felix Pappalardi (who later co-founded the Cream-influenced quartet Mountain) and engineer Tom Dowd, it was recorded at Atlantic Studios in New York. Disraeli Gears is often considered to be the band's defining effort, successfully blending psychedelic British rock with American blues. Disraeli Gears not only features hits "Strange Brew" and "Tales of Brave Ulysses", but also "Sunshine of Your Love".[7]

The album was originally slated for release in the summer of 1967, but the record label opted to scrap the planned cover and repackage it with a new psychedelic cover, designed by artist Martin Sharp, and the resulting changes delayed its release for several months. The album was remarkable for the time, with a psychedelic design patterned over a publicity photo of the trio.

Although the album is considered one of Cream's finest efforts, it has never been well represented in Cream's live sets. Although they consistently played "Tales of Brave Ulysses" and "Sunshine of Your Love", several songs from Disraeli Gears were quickly dropped from performances in mid-1967, favouring longer jams instead of short pop songs. "We're Going Wrong" was the only additional song from the album the group performed live. In fact, at their 2005 reunion shows in London, Cream played only three songs from Disraeli Gears: "Outside Woman Blues", "We're Going Wrong," and "Sunshine of Your Love." ("Tales of Brave Ulysses" was included in the band's 2005 New York performances, however.)

In August 1967, Cream played their first headlining dates in America, playing at the Fillmore West in San Francisco for the first time. The concerts were a great success and proved very influential on both the band itself and the flourishing hippie scene surrounding them. Upon discovering a growing listening audience, the band began to stretch out on stage, incorporating more time in their repertoire, some songs reaching jams of twenty minutes. Long drawn-out jams in numbers like "Spoonful", "N.S.U.", "I'm So Glad", and "Sweet Wine" became live favourites, while songs like "Sunshine of Your Love", "Crossroads", and "Tales of Brave Ulysses" remained reasonably short.

[edit] Wheels of Fire

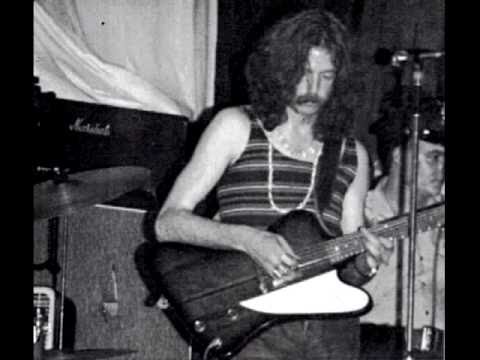

Eric Clapton performing after leaving Cream in Barcelona, 1974

In 1968 came Cream's third release, Wheels of Fire, which topped the American charts. Wheels of Fire studio recordings showcased Cream moving slightly away from the blues and more towards a semi-progressive rock style highlighted by odd time signatures and various orchestral instruments. However, the band did record Howlin' Wolf's "Sitting on Top of the World" and Albert King's "Born Under A Bad Sign". According to a BBC interview with Clapton, the record company, also handling Albert King, asked the band to cover "Born Under a Bad Sign", which became a popular track off the record. The opening song, "White Room", became a radio staple. Another song, "Politician", was written by the band while waiting to perform live at the BBC.[17] The album's second disc featured three live recordings from the Winterland Ballroom and one from the Fillmore. Eric Clapton's second solo from "Crossroads" has made it to the top 20 in multiple "greatest guitar solo" lists.[31][32]

After the completion of Wheels of Fire in mid-1968, the band members had had enough and wanted to go their separate ways. Baker stated in a 2006 interview with Music Mart magazine, "It just got to the point where Eric said to me: 'I've had enough of this,' and I said so have I. I couldn't stand it. The last year with Cream was just agony. It damaged my hearing permanently, and today I've still got a hearing problem because of the sheer volume throughout the last year of Cream. But it didn't start off like that. In 1966, it was great. It was really a wonderful experience musically, and it just went into the realms of stupidity." Bruce and Baker's combustible relationship proved even worse as a result of the strain put upon the band by non-stop touring, forcing Clapton to play the perpetual role of peacekeeper.

Clapton had also fallen under the spell of Bob Dylan's former backing group, now known as The Band, and their debut album, Music from Big Pink,[3] which proved to be a welcome breath of fresh air in comparison to the incense and psychedelia that had informed Cream. Furthermore, he had read a scathing Cream review in Rolling Stone, a publication he had much admired, in which the reviewer, Jon Landau, called him a "master of the blues cliché."[3] In the wake of that article, Clapton wanted to end Cream and pursue a different musical direction.

At the beginning of their farewell tour on 4 October 1968, in Oakland, nearly the entire set consisted of songs from Wheels of Fire: "White Room", "Politician", "Crossroads", "Spoonful", "Deserted Cities of the Heart", and "Passing the Time" taking the place of "Toad" for a drum solo. "Passing the Time" and "Deserted Cities" were quickly removed from the setlist and replaced by "Sitting on Top of the World" and "Toad".

[edit] Goodbye

Cream were eventually persuaded to do one final album. That album, the appropriately titled Goodbye, was recorded in late 1968 and released in early 1969, after the band had broken up. It featured six songs: three live recordings dating from a concert at The Forum in Los Angeles, California, on 19 October, and three new studio recordings (including "Badge", which was written by Clapton and George Harrison, who also played rhythm guitar as "L'Angelo Misterioso"). "I'm So Glad" was included among the live tracks.

Jack Bruce performing in 1972

Cream's "farewell tour" consisted of 22 shows at 19 venues in the United States between 4 October and 4 November 1968, and two final farewell concerts at the Royal Albert Hall on 26 November 1968. Initially another double album was planned, comprising live material from this tour plus new studio tracks, but a single album, Goodbye was released instead with three live tracks taken from their performance at The Forum in Los Angeles on 19 October 1968, and three studio tracks, one written by each of the band members. The final U.S. gig was at the Rhode Island Auditorium, 4 November 1968. The band arrived late and, due to local restrictions, they were able to perform only two songs, "Toad" and a 20+ minute version of "Spoonful". Bootlegs of inferior quality exist of the final US Concert.

The two Royal Albert Hall concerts were filmed for a BBC documentary and released on video (and later DVD) as Farewell Concert. Both shows were sold out and attracted more attention than any other Cream concert, but their performance was regarded by many as below standard. Baker himself said of the concerts: "It wasn’t a good gig ... Cream was better than that ... We knew it was all over. We knew we were just finishing it off, getting it over with." In an interview from Cream: Classic Artists, he added that the band was getting worse by the minute.[33]

Cream's supporting acts were Taste (featuring a young Rory Gallagher) and the newly formed Yes, who received good reviews. Three performances early in Cream's farewell tour were opened by Deep Purple. Deep Purple had originally agreed to open the entire U.S. leg of the tour, but Cream's management removed them after only three shows, in spite of favourable reviews and good rapport between the bands.[34]

From its creation, Cream were faced with some fundamental problems that would later lead to its dissolution in November 1968. The rivalry between Bruce and Baker created tensions in the band. Clapton also felt that the members of the band did not listen to each other enough. Equipment during these years had also improved; new Marshall amplifier stacks cranked out more power, and Jack Bruce pushed the volume levels higher, creating tension for Baker who would have trouble competing with roaring stacks. Clapton spoke of a concert during which he stopped playing and neither Baker nor Bruce noticed.[19] Clapton has also commented that Cream's later gigs mainly consisted of its members showing off.[35] Cream decided that they would break up in May 1968 during a tour of the US.[36] Later, in July, an official announcement was made that the band would break up after a farewell tour of the United States and after playing two concerts in London. Cream finished their tour of the United States with a 4 November concert in Rhode Island and performed in the UK for the last time in London on 25 and 26 November. Bruce had three Marshall stacks on stage for the farewell shows but one acted only as a spare, and he only used one or two, depending on the song.[36]

Blind Faith was formed immediately after the demise of Cream, following an attempt by Clapton to recruit Steve Winwood into the band in the hope that he would help act as a buffer between Bruce and Baker. Inspired by more song-based acts Clapton went on to perform much different, less improvisational material with Delaney & Bonnie, Derek and the Dominos and in his own long and varied solo career.

Bruce began a varied and successful solo career with the 1969 release of Songs for a Tailor, while Baker formed a jazz-fusion ensemble out of the ashes of Blind Faith called Ginger Baker's Air Force, which featured Winwood, Blind Faith bassist Rick Grech, Graham Bond on sax, and guitarist Denny Laine of the Moody Blues and (later) Wings.

In 1993, Cream were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and reformed to perform at the induction ceremony.[37] Initially, the trio were wary about performing, until encouraging words from Robbie Robertson inspired them to try.[citation needed] The set consisted of "Sunshine of Your Love", "Crossroads", and "Born Under a Bad Sign", a song they had not previously played live.[citation needed] Clapton mentioned in his acceptance speech that their rehearsal the day before the ceremony had marked the first time they had played together in 25 years.[3] This performance spurred rumours of a reunion tour.[citation needed] Bruce and Baker said in later interviews that they were, indeed, interested in touring as Cream.[citation needed] A formal reunion did not take place immediately, as Clapton, Bruce and Baker continued to pursue solo projects, although the latter two worked together again in the mid-1990s as two-thirds of a power trio BBM with Irish blues-rock guitarist Gary Moore.

Cream reunited for a series of four shows, on 2, 3, 5, and 6 May 2005 at the Royal Albert Hall in London, the venue of their final concerts in 1968, at Clapton's request.[38] Although the three musicians chose not to speak publicly about the shows, Clapton would later state that he had become more "generous" in regard to his past, and that the physical health of Bruce and Baker was a major factor:[38] Bruce had recently undergone a liver transplant for liver cancer, and had almost lost his life, while Baker had severe arthritis.

Tickets for all four shows sold out in under an hour. The performances were recorded for a live CD and DVD. Among those in attendance were Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, Steve Winwood, Roger Waters, Brian May, Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin and also Mick Taylor and Bill Wyman.[citation needed] The reunion marked the first time the band had played "Badge" and "Pressed Rat and Warthog" live.[38]

The Royal Albert Hall reunion proved a success on both a personal and financial level, inspiring the reformed band to bring their reunion to the United States. Cream chose to play at only one venue, Madison Square Garden in New York City, from 24–26 October 2005. The shows were marred by some controversy in regard to tickets:[citation needed] the show's promoters had made a deal with credit card company American Express to make tickets available to American Express customers only in an unprecedented week-long pre-sale. The shows were a financial success and received critical praise.[citation needed]

Fans of Cream hoped for a full-scale tour, but a statement from Cream's publicist days after the last performance put the nail in that particular coffin, when it was announced that Cream would not tour the United States. In an interview with Jack Bruce in the December 2005 issue of Bass Player magazine, Bruce hinted that he would like to see Cream continue in one way or another, possibly in the form of a new album, but that a tour was out of the question: "It would be quite a challenge to try to create music that would stand up to the classic songs. I've got a few ideas already—in fact, I wrote a song yesterday that I think would work. I just don't know if it will happen, because we all feel the band is so special we don't want to do it that often, if we go on. We've had offers you wouldn't believe—I didn't believe—for long world tours, and it's tempting. But none of us wants to accept because it would take away from the rarity and special nature of getting together. I'd like to do it every now and again and just play somewhere, but we could do an album amidst that, and I'm going to suggest it."

In February 2006, Cream received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of their contribution to, and influence upon, modern music.[39][40] That same month, a "Classic Albums" DVD was released detailing the story behind the creation and recording of Disraeli Gears. On the day prior to the Grammy ceremony, Bruce made a public statement that more one-off performances of Cream had been planned: multiple dates in a few cities, similar to the Royal Albert Hall and Madison Square Garden shows. However, this story was rebutted by both Clapton and Baker, first by Clapton in a Times article from April 2006. The article stated that when asked about Cream, Clapton said: "No. Not for me. We did it and it was fun. But life is too short. I've got lots of other things I would rather do, including staying at home with my kids. The thing about that band was that it was all to do with its limits ... it was an experiment." In an interview in the UK magazine Music Mart, about the release of a DVD about the Blind Faith concert in Hyde Park 1969, Baker commented about his unwillingness to continue the Cream reunion. These comments were far more specific and explosive than Clapton's, as they were centred around his relationship with Jack Bruce. Ginger said, "When he's Dr. Jekyll, he's fine... It's when he's Mr. Hyde that he's not. And I'm afraid he's still the same. I tell you this — there won't ever be any more Cream gigs, because he did Mr. Hyde in New York last year."[41]

When asked to elaborate, Baker replied: "Oh, he shouted at me on stage, he turned his bass up so loud that he deafened me on the first gig. What he does is that he apologises and apologises, but I'm afraid, to do it on a Cream reunion gig, that was the end. He killed the magic, and New York was like 1968... It was just a get through the gig, get the money sort of deal. I was absolutely amazed. I mean, he demonstrated why he got the sack from Graham Bond and why Cream didn't last very long on stage in New York. I didn't want to do it in the first place simply because of how Jack was. I have worked with him several times since Cream, and I promised myself that I would never work with him again. When Eric first came up with the idea, I said no, and then he phoned me up and eventually convinced me to do it. I was on my best behaviour and I did everything I could to make things go as smooth as possible, and I was really pleasant to Jack."[41]

Jack Bruce told Detroit's WCSX radio station in May 2007 that there were plans for a Cream reunion later in the year. It was later revealed that the potential performance was to be November 2007 London as a tribute to Ahmet Ertegün. The band decided against it and this was confirmed by Bruce in a letter to the editor of the Jack Bruce fanzine, The Cuicoland Express dated 26 September 2007:

- "Dear Marc,

- We were going to do this tribute concert for Ahmet when it was to be at the Royal Albert Hall but decided to pass when it was moved to the O2 Arena and seemed to be becoming overly commercial."

The headlining act for the O2 Arena Ertegun tribute show (postponed to December 2007) turned out to be another reunited English hard-rock act, Led Zeppelin. So while the band members are all still alive and talking again, no Cream reunions are planned for the near future.

In an interview with BBC 6 Music in April 2010, Bruce confirmed that there would be no more Cream shows. He said: "Cream is over."[42]

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Richie. "Cream: Biography". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/artist/p3983. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ "Cream – the Band". BBC. 20 September 2000. http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A425774. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cream: Classic Artists (DVD). Image Entertainment. 2007.

- ^ "The world's 18 biggest supergroups". Musicradar.com. 2009-04-15. http://www.musicradar.com/news/guitars/the-worlds-18-biggest-supergroups-203302. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ^ "Supergroup Cream rises again". CNN.com. 1999-12-20. http://www.cnn.com/2005/SHOWBIZ/Music/05/03/cream.reunion.concert/index.html. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ^ Whereseric.com[dead link]

- ^ a b c Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 53 – String Man. : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc19835/m1/.

- ^ "Time, Cream article". Time.com. 9 March 2009. http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1883726_1883727_1883724,00.html. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ^ a b c "Cream: Biography: Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/cream/biography. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ "Badge" search results. http://www.everyhit.com. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "allmusic (((Rush > Overview)))". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/artist/p5323. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ "allmusic (((Black Sabbath > Overview)))". Allmusic. http://www.allmusic.com/artist/p3693. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ "Cream: inducted in 1993". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved 25 April 2012

- ^ "The Greatest Artists of All Time". VH1/Stereogum. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Waters, Roger. "Cream: 100 Greatest Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 April 2012

- ^ "VH1's 100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock (20–1)". VH1. 2000. http://www.vh1.com/shows/dyn/the_greatest/62188/episode_wildcard.jhtml?wildcard=/shows/dynamic/includes/wildcards/the_greatest/hardrock_list_full.jhtml&event_id=862769&start=81. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ a b McDermott, John (November 1997). "Strange Brew". Guitar World magazine

- ^ Clapton, Eric (2007). Clapton: The Autobiography. New York, United States: Broadway Books. pp. g. 74. ISBN 978-0-385-51851-2.

- ^ a b c White, Dave. "Cream". about.com. http://classicrock.about.com/od/bandsandartists/p/Cream.htm. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- ^ a b Clapton, Eric (2007). Clapton: The Autobiography. United States: Broadway Books. pp. g. 77. ISBN 978-0-385-51851-2.

- ^ Ertegün, Ahmet (2006). Classic Albums: Cream – Disraeli Gears (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ Cream (1966). Fresh Cream

- ^ a b Cream (1967). Disraeli Gears

- ^ Cream (1967). Disraeli Gears"

- ^ Cream (1968).

- ^ Cream (1968). Wheels of Fire

- ^ Cream (1969). Goodbye (1969)

- ^ Pattingale, Graeme (17 January 1999). "Fresh Cream". http://twtd.bluemountains.net.au/cream/fresh.htm. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ GP Flashback : Cream, June 1967 – Guitar Player Article – June 1967

- ^ Pattingale, Graeme (19 November 1998). "Disraeli Gears". http://twtd.bluemountains.net.au/cream/disraeli.htm. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ "The 25 Coolest Guitar Solos". Rolling Stone. 6 August 2007. http://www.rollingstone.com/rockdaily/index.php/2007/08/06/the-25-coolest-guitar-solos/. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Guitar Solos". Guitar World Magazine. http://guitar.about.com/library/bl100greatest.htm. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Pattingale, Graeme (2002). "A Guide to the Bootlegs". http://twtd.bluemountains.net.au/cream/bootlegguide.htm. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple ... – Google Books. Books.google.com. 2004. ISBN 978-1-55022-618-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=LzzCw6xs9roC. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Clapton, Eric (8 October 2007). "Eric Clapton Chronicles Music, Addiction and Romance in New Book". Clapton: The Autobiography. spinner.com. http://www.spinner.com/2007/10/08/eric-clapton-chronicles-music-addiction-and-romance-in-new-book/. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ a b Welch, Chris (4 August 2005). "The Farewell". http://www.cream2005.com/theband_farewell.lasso. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "Cream". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. http://www.rockhall.com/inductee/cream. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ a b c Bruce, Jack; Baker, Ginger; Clapton, Eric (2005). "Interview", Royal Albert Hall London May 2-3-5-6, 2005 special feature (DVD). Rhino Entertainment.

- ^ Cream: Biography. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 April 2012

- ^ Grammys To Salute Bowie, Cream, Haggard, Pryor. Billboard. Retrieved 25 April 2012

- ^ a b "Ginger Baker Interview". Slowhand. http://six.pairlist.net/pipermail/slowhand/2006/009492.html. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ^ "6Music News - Jack Bruce's Cream". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/6music/news/20100411_cream.shtml. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

|

Cream

|

|

|

|

|

| Studio albums |

|

|

| Live albums |

|

|

| Compilations |

|

|

| Singles |

|

|

| Other songs |

|

|

| Collaborators |

|

|

| Related articles |

|

|

|

|

|

![La Cream - Say Goodbye [HD] La Cream - Say Goodbye [HD]](http://web.archive.org./web/20121117082111im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/SLqgCKHQO6A/default.jpg)