Brittany

Bretagne / Breizh / Bertaèyn |

|

|

Motto: Kentoc'h mervel eget bezañ saotret

Rather death than dishonour |

Anthem: None (de jure)

De facto "Bro Gozh ma Zadoù"

Old Land of My Fathers |

|

Location of Brittany (dark blue) within the European Union (light blue) |

| Country |

France France |

| Largest settlements |

|

| Area |

| • Total |

34,023 km2 (13,136 sq mi) |

| Population (January 2007 estimate) |

| • Total |

4,365,500 |

| Time zone |

CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) |

CEST (UTC+2) |

Brittany (French: Bretagne [bʁətaɲ] ( listen); Breton: Breizh, pronounced [brɛjs]; Gallo: Bertaèyn) is a cultural region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain (as opposed to Great Britain). Brittany is considered as one of the six Celtic nations.[1][2][3][4]

listen); Breton: Breizh, pronounced [brɛjs]; Gallo: Bertaèyn) is a cultural region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain (as opposed to Great Britain). Brittany is considered as one of the six Celtic nations.[1][2][3][4]

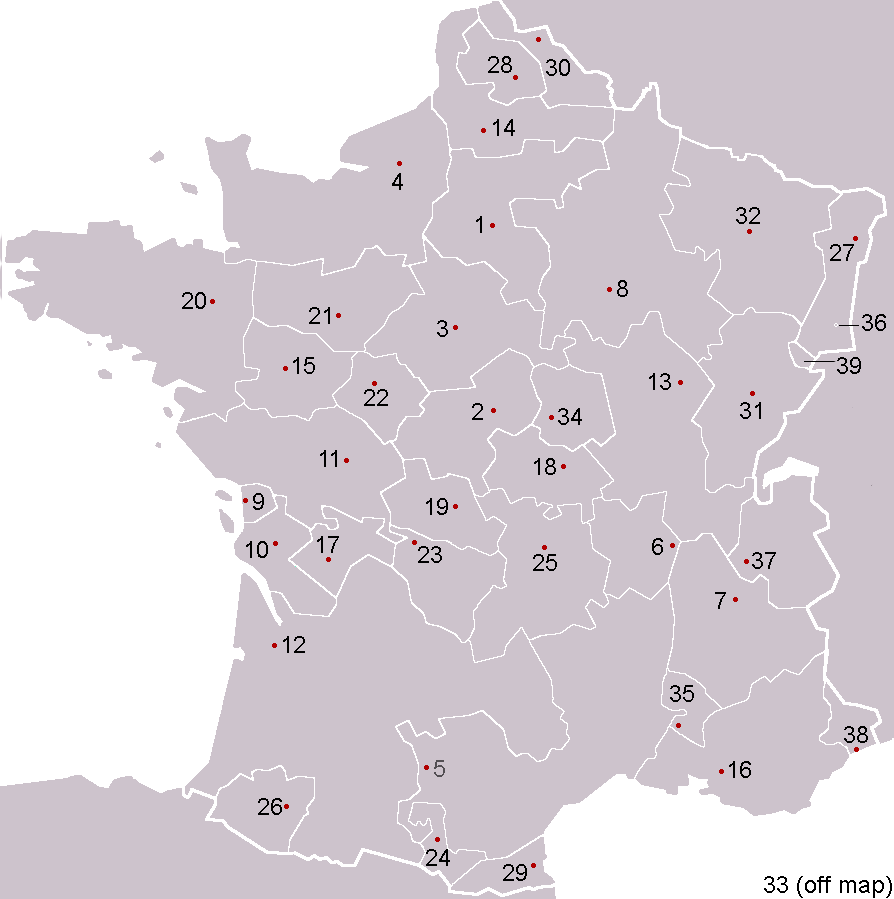

Brittany occupies the northwest peninsula of continental Europe in northwest France. It is bordered by the English Channel to the north, the Celtic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Bay of Biscay to the south. Its land area is 34,023 km² (13,136 sq mi). The historical province of Brittany is divided into five departments: Finistère in the west, Côtes-d'Armor in the north, Ille-et-Vilaine in the north east, Loire-Atlantique in the south east and Morbihan in the south on the Bay of Biscay.

In 1956, French regions were created by gathering departments between them.[5] The Region of Brittany comprises, since then, four of the five Breton departments (80% of historical Brittany), while the remaining area of the old Brittany, the Loire-Atlantique department, around Nantes, forms part of the Pays de la Loire region. This territorial organisation is regularly contested. The Kingdom and the Duchy of Brittany, the province of Brittany, and the modern Region of Brittany cover the Western part of Armorica, as it was known during the period of Roman occupation.

In January 2007 the population of historic Brittany was estimated to be 4,365,500. Of these, 71% lived in the region of Brittany, while 29% lived in the region of Pays-de-la-Loire. At the 1999 census, the largest metropolitan areas were Nantes (711,120 inhabitants), Rennes (521,188 inhabitants), and Brest (303,484 inhabitants).

The peninsula that came to be known as Brittany was a centre of ancient megalithic constructions in the Neolithic era. It has been called the "core area" of megalithic culture.[6] It later became the territory of several Celtic tribes, of which the most powerful was the Veneti. After Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul, the area became known to the Romans as Armorica, from the Celtic term for "coastal area". Its transformation into Brittany occurred in the late Roman period, with the establishment of Romano-British settlement in the area. The history behind such an establishment is unclear, but medieval Breton and Welsh sources connect it to a figure known as Conan Meriadoc. Welsh literary sources assert that Conan came to Armorica with the Roman usurper Magnus Maximus, who took his British troops to Gaul to enforce his claims and settled them in Armorica. Regardless of the truth of this story, Brythonic (British Celtic) settlement probably increased during the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain in the 5th century. Scholars such as Léon Fleuriot have suggested a two-wave model of migration from Britain which saw the emergence of an independent Breton people and established the dominance of the Brythonic Breton language in Armorica.[7] Over time the Armorican British colony expanded, forming a group of petty kingdoms which were later unified in the 840s under Nominoe in resistance to Frankish control.[8]

Historical regions of Brittany in the 14th century

In the mid-9th century Nominoe and his successors won a series of victories over the Franks which secured an independent Duchy of Brittany. In the High Middle Ages the Duchy was sometimes allied to England and sometimes to France. The pro-English faction was victorious in 1364 in the Breton War of Succession, but the independent Breton army was eventually defeated by the French in 1488, leading to dynastic union with France following the marriage of Duchess Anne of Brittany to two kings of France in succession.[9] In 1532 the Duchy was incorporated into France.

Two significant revolts occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries: the Revolt of the papier timbré (1675) and the Pontcallec Conspiracy (1719). Both arose from attempts to resist centralisation and assert Breton constitutional exceptions to tax.[10] The Duchy was legally abolished during the French Revolution and divided into five departments. The area became a centre of royalist and Catholic resistance to the Revolution during the Chouannerie. During the Second Empire conservative Catholic values were reasserted. When the Republic was reinstituted in 1871, there were rumours that Breton troops were mistrusted and mistreated at Camp Conlie during the Franco-Prussian War because of fears that they were a threat to the Republic.[11]

In the 19th century the Celtic Revival led to the foundation of the Breton Regionalist Union (URB) and later to independence movements linked to Irish, Welsh and Scottish independence parties in the UK and to pan-Celticism. There was a cultural renaissance in the 20th century associated with the movement Seiz Breur.[12] The alliance of the Breton National Party with Nazi Germany in World War II weakened Breton nationalism in the post-war period. In 1956, Brittany was legally reconstituted as the Region of Brittany, although the region excluded the ducal capital of Nantes and the surrounding area. Over this period the Breton language declined precipitously. Children were not allowed to speak Breton at school, and were punished by teachers if they did. Famously, signs in schools read: "It is forbidden to speak Breton and to spit on the floor" ("Il est interdit de parler breton et de cracher par terre").[13] As a result, a generation of native Breton speakers were made to feel ashamed of their language and avoided speaking it or teaching it to their children. These factors contributed to the decline of Breton. Nevertheless Brittany retained its cultural distinctiveness.

Brittany is home to many megalithic monuments which are scattered across the peninsula. The largest alignments are near Karnag/Carnac. The purpose of these monuments is still unknown, and many local people are reluctant to entertain speculation on the subject.

Brittany is also known for its calvary sculptures, elaborately carved crucifixion scenes found at crossroads in villages and small towns, especially in Western Brittany.

Besides its numerous intact manors and châteaux, Brittany also has several old fortified towns. The walled city of Saint-Malo (Sant-Maloù), a popular tourist attraction, is also an important port linking Brittany with England and the Channel Islands. It was the birthplace of the historian Louis Duchesne, the acclaimed author Chateaubriand, the corsair Surcouf and the explorer Jacques Cartier. The town of Roscoff (Rosko) is served by ferry links with England and Ireland.

Significant urban centres include:

-

- Nantes (Gallo: Naunnt, Breton: Naoned) : 282,853 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 804,833 in the urban area.

- Rennes (Gallo: Resnn, Breton: Roazhon) : 209,613 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 521,188 in the urban area.

- Brest (Breton Brest) : 148,316 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 300,000 in the urban area.

- Saint-Nazaire (Gallo: Saint-Nazère, Breton: Sant-Nazer) : 71,373 inhabitants in the commune (2006); located in the urban area of Nantes.

- Lorient (Breton: an Oriant) : 58,547 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 190,000 in the urban area.

- Quimper (Breton: Kemper) : 64,900 inhabitants in the commune (2006).

- Vannes (Breton: Gwened, Gallo: Vann) : 53,079 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 132,880 in the urban area.

- Saint-Brieuc (Gallo: Saint-Bérieu, Breton: Sant-Brieg) : 46,437 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 121,237 in the urban area (2005).

- Saint-Malo (Gallo: Saent-Malô, Breton: Sant-Maloù) : 52,737 inhabitants in the commune (2007), 81,962 in the urban area.

- Redon (Gallo: Rdon, Breton: Redon) : 9,601 inhabitants in the commune (2006), 52,758 in the urban area.

The island of Ushant (Breton: Enez Eusa, French: Ouessant) is the north-westernmost point of Brittany and France, and marks the entrance to the English Channel. Other islands off the coast of Brittany include:

-

The coast at Brittany is unusual due to its colouring. The Côte de Granit Rose (pink granite coast) is located in the Côtes d'Armor department of Brittany. It stretches for more than 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Plestin-les-Greves to Louannec and is one of the outstanding coastlines of Europe. This special pink rock is very rare and can be found in only three other places in the world, Ontario, Canada, Corsica and China.[14]

The landscape has inspired artists, including Paul Signac, Marc Chagall, Raymond Wintz and his wife Renee Carpentier Wintz, who both painted coastal and village scenes. Paul Gauguin and his famous School of Pont-Aven in the Finistère department, Brittany also painted many village scenes.

The Breton musical group

Kevrenn Alre at the Festival Interceltique de Lorient

Brittany has a vibrant calendar of festivals and events. Several are of course maritime themed while others reflect Brittany’s lively music heritage or the region’s diverse culture. Traditional Breton festivals, fest noz in Breton, regularly take place in towns and villages throughout Brittany and include local music and dancing. Brittany also hosts some of France’s biggest contemporary music festivals.

Cultural festivals

- Festival de Cornouaille: July (Quimper, Finistère)

A long-established festival that showcases Brittany’s cultural diversity.

- Les Filets Bleus: August (Concarneau, Finistère)

This long-standing festival celebrates fishing traditions in the coastal town of Concarneau.

An internationally renowned festival that celebrates Celtic traditions.

- Festival du Film Britannique: October (Dinard,Côtes-d’Armor)

This British film festival screens previews of British films in France.

Music festivals

- Art Rock: May (Saint-Brieuc, Côtes d'Armor)

Pop, rock and electro festival.

This music festival is the Breton equivalent of Glastonbury in the UK.

- Astropolis: July (Brest, Finistère)

A prominent electro and techno festival.

Pop and rock, often with an Anglo-Saxon flavour.

Known for showcasing brand new acts : Nirvana and Portishead did some of their early gigs at this festival.

Maritime festivals

- Fêtes Maritimes de Brest: July (Brest, Finistère)

This sailing event takes place every 4 years (the next one is in 2012).

This transatlantic single-handed yacht race takes place every 4 years (the next one is in 2014).

Lower Brittany (in colours), where the Breton language is traditionally spoken and

Upper Brittany (in shades of grey), where the Gallo language is traditionally spoken. The changing shades indicate the advance of Gallo and French, and retreat of Breton from AD900.

Bilingual road signs can be seen in traditional Breton-speaking areas.

French, the only official language of the French Republic, is today spoken throughout Brittany. The two regional languages are supported by the regional authorities within the constitutional limits: Breton, strongest in the west but to be seen all over Brittany, is a Celtic language most closely related to Cornish and Welsh. Gallo, which is spoken in the east, is one of the romance Langues d'oïl.

Breton was traditionally spoken in the west (Breton: Breizh-Izel, or Lower Brittany), and Gallo in the east (French: pays Gallo, Breton: Breizh Uhel, Gallo: Haùtt-Bertaèyn, or Upper Brittany). The dividing line stretched from Plouha on the north coast to a point to the south east of Vannes. French had, however, long been the main language of the towns. The Breton-speaking area once covered territory much farther east than its current distribution.

Since the 13th century, long before the union of Brittany and France, the main administrative language of the Duchy of Brittany was French, and previously it was Latin. Breton (in the West) and Gallo (in the East) remained the two languages of the rural population of Brittany, but since the Middle Ages the bourgeoisie, the nobility, and the higher clergy spoke French. Government policies in the 19th and 20th centuries, which forbade the speaking of Breton in schools, along with the demands of education, pushed many non-French speakers into adopting the French language. Nevertheless, until the 1960s Breton was spoken and understood by most of the inhabitants of western Brittany.

In the Middle Ages, Gallo gradually expanded into formerly Breton-speaking areas. Now restricted to a much reduced territory in the east of Brittany, Gallo finds itself under pressure from the dominant Francophone culture. It is also felt by some to be threatened by the Breton language revival, which is gaining ground in territories that were not previously part of the main Breton-speaking area.

Diwan ("seed") schools, where classes are taught in Breton by the immersion method, play an important part in the revival of the Breton language. These schools are privately funded, as they receive no French central government support. The issue of whether they should be funded by the State has long been, and remains, controversial. Some bilingual classes are also provided in ordinary schools.[citation needed]

Bilingual (Breton and French) road signs may be seen in some areas, especially in the traditional Breton-speaking area of Lower Brittany. Signage in Gallo is much rarer.

Some villages have received an influx of English-speaking immigrants and second-home owners, adding to the linguistic diversity.

Be Breizh: Breizh is the Breton word for Brittany and given that the Bretons are particularly proud of their roots, you will see the word – or simply the letters BZH – in evidence throughout the region. Along with the black and white Breton flag (the Gwenn Ha Du) and the triskell, you will see these symbols of Breton identity on cars, t-shirts and shop fronts. In 2011, the regional tourist board adopted the phrase ‘Be Breizh’ to sum up this unique Breton spirit.

Sculpted "calvaries" can be found in many villages.

The Notre-Dame church in

Bodilis, Finistère

While Christianization may have occurred during Roman occupation, the first recorded Christian missionaries came to the region from Wales and are known as the "Seven founder saints":

- St Pol Aurelian, at Saint-Pol-de-Léon (Breton: Kastell-Paol),

- Saint Tudwal (sant Tudwal), at Tréguier (Breton: Landreger),

- St Brioc, at Saint-Brieuc (Breton: Sant-Brieg, Gallo: Saent-Berioec),

- St Malo, at Saint-Malo (Breton: Sant-Maloù, Gallo: Saent-Malô),

- St Samson of Dol, at Dol-de-Bretagne (Breton: Dol, Gallo: Dóu),

- St Patern, at Vannes (Breton: Gwened),

- St Corentin (sant Kaourintin), at Quimper (Breton: Kemper).

Other notable early evangelizers are Gildas and the Irish saint Columbanus. With more than 300 "saints" (only a few recognised by the Catholic Church), the region is strongly Catholic. Since the 19th century at least, Brittany has been known as one of the most devoutly Catholic regions in France, in contrast to many other more secularised areas (see "Bl. Julien Maunoir"). The proportion of students attending Catholic private schools is the highest in France. As in other Celtic regions, the legacy of Celtic Christianity has left a rich tradition of local saints and monastic communities, often commemorated in place names beginning Lan, Lam, Plou or Lok. The patron saint of Brittany is Saint Anne, the Virgin's mother. But the most famous saint is Saint Ivo of Kermartin ('saint Yves' in French, 'sant Erwan' in Breton), a 13th century priest who devoted his life to the poor.

Once a year, believers go on a "Pardon", the saint's feast day of the parish. It often begins with a procession followed by a mass in honour of the saint. There is always a secular side, with some food and craft stalls. The three most famous Pardons are:

- from Sainte-Anne d'Auray/Santez-Anna-Wened, where a poor farmer in the 17th century explained how the saint had ordered him to build a chapel in her honour.

- from Tréguier/Landreger, in honour of St Yves, the patron saint of the judges, advocates, and any profession involved in justice.

- from Locronan/Lokorn, in honour of St Ronan, with a troménie (a procession, 12 km-long) and numerous people in traditional costume (Locronan is also very close to a more known city Douarnenez which used to be the very famous rendez-vous point for all sailers in the world every 4 years).

There is a very old pilgrimage called the Tro Breizh (tour of Brittany), where the pilgrims walk around Brittany from the grave of one of the seven founder saints to another. Historically, the pilgrimage was made in one trip (a total distance of around 600 km) for all seven saints. Nowadays, however, pilgrims complete the circuit over the course of several years. In 2002, the Tro Breizh included a special pilgrimage to Wales, symbolically making the reverse journey of the Welshmen Sant Paol, Sant Brieg, and Sant Samzun. It is believed that whoever does not make the pilgrimage at least once in his lifetime will be condemned to make it after his death, advancing only by the length of his coffin each seven years.[15]

Many distinctive traditions and customs have also been preserved in Brittany. The most powerful folk figure is the Ankou or the "Reaper of Death". Sometimes a skeleton wrapped in a shroud with the Breton flat hat, sometimes described as a real human being (the last dead of the year, devoted to bring the dead to Death), he makes his journeys by night carrying an upturned scythe which he throws before him to reap his harvest. Sometimes he is on foot but mostly he travels with a cart, the Karrig an Ankou, drawn by two oxen and a lean horse. Two servants dressed in the same shroud and hat as the Ankou pile the dead into the cart, and to hear it creaking at night means you have little time left to live.[16]

Brittany is an area of strong Celtic heritage, rich in its cultural heritage. Though long under the control of France and influenced by French traditions, Brittany has retained and, since the early 1970s, revived its own folk music, modernising and adapting it into folk rock and other fusion genres (see, for example, Alan Stivell, Dan Ar Braz, and Red Cardell).

A Galette with savory stuffing.

Although some white wine is produced near the Loire, the traditional drinks of Brittany are:

- cider (Breton: sistr or chistr) – Brittany is the second largest cider-producing region in France;[17] Traditionally served in a ceramic cup resembling an English Tea cup ("bolennad" in breton, "bolée" in french).

- beer (Breton: bier) – Brittany has a long beer brewing tradition, tracing its roots back to the seventeenth century; Young artisanal brewers are keeping a variety of beer types alive,[18] such as Coreff de Morlaix, Tri Martolod and Britt;

- a sort of mead made from wild honey called chouchenn;

- an apple eau de vie called lambig.

Historically Brittany was a beer producing region. However, as wine was increasingly imported from other regions of France, beer drinking and production slowly came to an end in the early to mid-20th century. In the 1970s, due to a regional comeback, new breweries started to open and there are now about 20 of them. Whisky is also produced by a handful of distilleries with excellent results, such as Eddu distillery at Plomelin near Quimper, which elaborates a real and successful creation using buckwheat, Glann ar Mor distillery which makes an un-peated Single Malt, as well as a peated expression named Kornog. Another recent drink is kir Breton (crème de cassis and cider) which may be served as an apéritif. Tourists often try a mix of bread and red wine. Large, thin pancakes made from buckwheat flour (blé noir) are eaten with ham, eggs and other savoury fillings. They are made with plain buckwheat flour and water in Eastern Brittany and called galettes (Breton: galetes). La Galette Saucisse, a hot grilled pure pork Breton sausage wrapped in a cold galette, is the "fast food" of Eastern Brittany, sold from road side stands, and served at every occasion from football matches to the local school fête.[19] In the western parts of Brittany buckwheat pancakes are made with eggs and called crêpes de blé noir (Breton: krampouezh). Galettes are often served with a cup of cider, but in Brittany they should traditionally be accompanied by Breton buttermilk called lait ribot (Breton: laezh-ribod). Brittany also has a dish similar to the pot-au-feu known as the Kig ha farz, which consists of stewed pork or beef with buckwheat dumplings.

Thin crêpes made from wheat flour are eaten for dessert or for breakfast. They may be served cold with local butter. Other pastries, such as kouign amann ("butter cake" in Breton) made from bread dough, butter and sugar, or far, a sort of sweet Yorkshire pudding, or clafoutis with prunes, are traditional.

Surrounded by the sea, Brittany offers a wide range of fresh sea food and fish, especially mussels and oysters. Among the sea food specialities is cotriade.

Located on the west coast of France, Brittany has a warm, temperate climate. Rainfall occurs regularly – which has helped keep its countryside green and wooded, but sunny, cloudless days are also common.

In general, Brittany has a moderate climate during both summer and winter. In the summer months temperatures in the region can reach 30 °C (86 °F), yet the climate remains comfortable, especially when compared to parts of France south of the Loire. In Brittany a common expression and response to people complaining about the rain is "En Bretagne, il ne pleut que sur les cons", which literally translates as "In Brittany, it only rains on the idiots", and should be understood as if one is not pleased with Brittany, he should leave it.

Brittany's most popular summer resorts are on the south coast (La Baule, Belle Île, Gulf of Morbihan), although the wilder and more exposed north coast (the Côte de granite rose, Perros-Guirec, etc.) also attracts summer tourists.

MV

Pont-Aven, the flagship that serves the routes connecting Brittany to England and

Ireland

Airports in Brittany serving destinations in France, Great Britain and Ireland include Brest, Saint-Malo, Lorient and Rennes. Flights between Brittany and the Channel Islands are served by Saint-Brieuc airport. Several cities in Great Britain and Ireland are also served from Nantes, Loire-Atlantique department and former capital of the historic province of Brittany. The main airlines include, among others, Ryanair, Flybe, Aer Arann, Aer Lingus, Air France and EasyJet.

Others smaller airport operates domestic flights in Quimper, and Lannion

TER Bretagne is the regional train that operates in Brittany and the TGV train services link the region with cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille, and Lille in France. In addition there are ferry services that take passengers, vehicles and freight to Ireland, England and the Channel Islands.

Brittany Ferries operates the following regular services:

Irish Ferries operates the following routes:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Timber Framed houses at Place Rallier du Baty in Rennes

-

- ^ "The Celtic League". The Celtic League. http://www.celticleague.net/. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Festival Interceltique de Lorient 2010". Festival Interceltique de Lorient. http://www.festival-interceltique.com/festival/nations-celtes.cfm. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Official website of the French Government Tourist Office: Brittany". Us.franceguide.com. http://us.franceguide.com/Cultural-Brittany.html?NodeID=1&EditoID=193027. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ The Celtic connection. Google Books. 30 March 1986. http://books.google.com/books?id=iKIWY4P9uFwC. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ Michèle Cointet, op. cit., pp. 183–216 (p. 216 pour la citation)

- ^ Mark Patton, Statements in Stone: Monuments and Society in Neolithic Brittany, Routledge, 1993, p.1

- ^ Léon Fleuriot, Les origines de la Bretagne: l’émigration, Paris, Payot, 1980.

- ^ Smith, Julia M. H. Province and Empire: Brittany and the Carolingians, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.80–83.

- ^ Constance De La Warr, A Twice Crowned Queen: Anne of Brittany, Peter Owen, 2005

- ^ Joël Cornette, Le marquis et le Régent. Une conspiration bretonne à l'aube des Lumières, Paris, Tallandier, 2008.

- ^ "Rennes, guide histoire" (PDF). http://www.rennes.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/Telechargements/rennais/rn382/histoire.pdf. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ J. R. Rotté, Ar Seiz Breur. Recherches et réalisations pour un art Breton moderne, 1923–1947, 1987.

- ^ Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l ... – Google Books. Google Books. 19 June 2008. http://books.google.com/books?id=h99nAAAAMAAJ&q=%22Il+est+interdit+de+parler+breton+et+de+cracher+par+terre%22&dq=%22Il+est+interdit+de+parler+breton+et+de+cracher+par+terre%22&ei=BcJMS8PWMILmzASN-dn2Cw&cd=2. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Cote de Granit Rosé (pink granite coast)". Frenchconnections.co.uk. http://www.frenchconnections.co.uk/en/guide/miniguidepage/150687-cote-de-granit-ros%C3%A9---brittany. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ Bretagne: poems (in French), by Amand Guérin, Published by P. Masgana, 1842: page 238

- ^ Anatole le Braz, La Legende de la Mort, BiblioBazaar reprint, LLC, 2009, pp. 430ff.

- ^ "Le Cidre – Mediaoueg , Ar Vediaoueg – La Médiathèque". Servijer.net. http://servijer.net/mediaoueg/Le-Cidre. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "bierbreizh – Accueil". Bierbreizh.info. http://www.bierbreizh.info/. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Galette saucisse – Wikipédia" (in (French)). Fr.wikipedia.org. 25 April 2011. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galette_saucisse. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

Coordinates: 48°00′N 3°00′W / 48°N 3°W / 48; -3

![Paul Oakenfold feat Brittany Murphy - Faster Kill Pussycat [HD]](http://web.archive.org./web/20121025004218im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/gyTPfifzqjo/0.jpg)