- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

A. N. Prahlada Rao

A. N. Prahlada Rao (born 24 July 1953) is an Indian author and Kannada crossword writer who has created the highest number of crosswords in India.

http://wn.com/A_N_Prahlada_Rao -

Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn ( or ); (c.1501/1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536 as the second wife of Henry VIII of England and 1st Marquess of Pembroke in her own right for herself and her descendants. Henry's marriage to Anne, and her subsequent execution, made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that was the start of the English Reformation. The daughter of Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire and his wife, Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire, Anne was educated in the Netherlands and France, largely as a maid of honour to Claude of France. She returned to England in early 1522, in order to marry her Irish cousin James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond; however, the marriage plans ended in failure and she secured a post at court as maid of honour to Henry VIII's Queen consort, Catherine of Aragon.

http://wn.com/Anne_Boleyn -

Arthur Wynne

Arthur Wynne (1862 - 1945), born Liverpool, England, was a British editor and puzzle constructor in his home country and the United States. After coming to the United States, he was a resident of Cedar Grove, New Jersey. He invented the crossword puzzle in 1913.

http://wn.com/Arthur_Wynne -

Clare Briggs

Clare A. Briggs (August 5, 1875 – January 3, 1930) was an early American comic strip artist who rose to fame in 1904 with his strip A. Piker Clerk.

http://wn.com/Clare_Briggs -

Emily Cox (compiler)

http://wn.com/Emily_Cox_(compiler) -

Eugene T. Maleska

http://wn.com/Eugene_T_Maleska -

Georges Perec

Georges Perec (7 March 1936, Paris – 3 March 1982) was a French novelist, filmmaker and essayist. He was a member of the Oulipo group.

http://wn.com/Georges_Perec -

Henry Rathvon

Henry Rathvon is a puzzle writer. He and his partner, Emily Cox, write The Atlantic Puzzler, a cryptic crossword featured each month in the magazine The Atlantic Monthly since 1977. (Since March 2006, the Puzzler has been published solely online at The Atlantic's website.) They also create acrostic puzzles for the New York Times, cryptic crosswords for Canada's National Post, puzzles for the US Airways in-flight magazine, and (with Henry Hook) Sunday crosswords for the Boston Globe.

http://wn.com/Henry_Rathvon -

Leonard Dawe

Leonard Sydney Dawe (3 November 1889 – 12 January 1963) was an English amateur footballer who played in the Southern League for Southampton between 1912 and 1913, and made one appearance for the England national amateur football team in 1912. He later became a schoolteacher and crossword compiler for The Daily Telegraph newspaper and in 1944 was interrogated on suspicion of espionage in the run-up to the D-Day landings.

http://wn.com/Leonard_Dawe -

Manny Nosowsky

Manny Nosowsky (b. January, 1932, San Francisco, CA) is a U.S. crossword puzzle creator. A medical doctor by training, he retired from a San Francisco urology practice and, beginning in 1991, has created crossword puzzles that have been published in The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and many other newspapers. Will Shortz, the crossword puzzle editor for The New York Times, has described Nosowsky as "a national treasure"[http://www.cruciverb.com/index.php/articles/news/254] and included four Nosowsky puzzles in his 2002 book, ''Will Shortz's Favorite Crossword Puzzles. Since Shortz became editor of the Times crossword in November 1993, Nosowsky has published nearly 250 puzzles there, making him by far the most prolific published constructor in the Times''. [http://wordplay.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/12/nowsowsky/] Nosowsky is frequently chosen to produce puzzles for the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament.[http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2006/06/25/CMG1QJ740C1.DTL&type;=printable]

http://wn.com/Manny_Nosowsky -

Margaret Farrar

Margaret Petherbridge Farrar (March 23, 1897 – June 11, 1984) was an American journalist and the first crossword puzzle editor for the New York Times, from 1942 to 1968. Stanley Newman has referred to her as a "crossword genius", and credits her with the creation of "many, if not most" of the rules that guide modern crossword design.

http://wn.com/Margaret_Farrar -

Roger Squires

Roger Squires (born 22 February 1932, in Tettenhall, Wolverhampton, England) is a British crossword compiler, living in Ironbridge, Shropshire, who is best known for being the world's most prolific compiler .

http://wn.com/Roger_Squires -

Stephen Sondheim

Stephen Joshua Sondheim (born March 22, 1930) is an American composer and lyricist for stage and film. He is the winner of an Academy Award, multiple Tony Awards (eight, more than any other composer) including the Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Theatre, multiple Grammy Awards, and a Pulitzer Prize. His most famous scores include (as composer/lyricist) A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Assassins, as well as the lyrics for West Side Story and . He was president of the Dramatists Guild from 1973 to 1981.

http://wn.com/Stephen_Sondheim -

The Times

The Times is a daily national newspaper published in the United Kingdom since 1785, when it was known as The Daily Universal Register.

http://wn.com/The_Times -

Will Weng

Will Weng (February 25, 1907 – May 2, 1993) was an American journalist and crossword puzzle constructor who served as crossword puzzle editor for New York Times from 1969-1977.

http://wn.com/Will_Weng

-

Australia

{{Infobox country

http://wn.com/Australia -

Bangalore

Bangalore , known as Bengaluru (), is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. Bangalore is nicknamed the Garden City and was once called a pensioner's paradise. Located on the Deccan Plateau in the south-eastern part of Karnataka, Bangalore is India's third most populous city and fifth-most populous urban agglomeration. As of 2009, Bangalore was inducted in the list of Global cities and ranked as a "Beta World City" alongside Geneva, Copenhagen, Boston, Cairo, Riyadh, Berlin, to name a few, in the studies performed by the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network in 2008.

http://wn.com/Bangalore -

Eugene T. Maleska

http://wn.com/Eugene_T_Maleska -

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island. With a population of about 60.0 million people in mid-2009, it is the third most populated island on Earth. Great Britain is surrounded by over 1,000 smaller islands and islets. The island of Ireland lies to its west. Politically, Great Britain may also refer to the island itself together with a number of surrounding islands which comprise the territory of England, Scotland and Wales.

http://wn.com/Great_Britain -

India

India (), officially the Republic of India ( ; see also official names of India), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.18 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world. Mainland India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the west, and the Bay of Bengal on the east; and it is bordered by Pakistan to the west; Bhutan, the People's Republic of China and Nepal to the north; and Bangladesh and Burma to the east. In the Indian Ocean, mainland India and the Lakshadweep Islands are in the vicinity of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, while India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands share maritime border with Thailand and the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the Andaman Sea. India has a coastline of .

http://wn.com/India -

Ironbridge

Ironbridge is a settlement on the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, in Shropshire, England. It lies in the civil parish of The Gorge, in the borough of Telford and Wrekin. Ironbridge developed beside, and takes its name from, the famous Iron Bridge, a 30 metre (100 ft) cast iron bridge that was built across the river there in 1779.

http://wn.com/Ironbridge -

Italy

Italy (; ), officially the Italian Republic (), is a country located in south-central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia along the Alps. To the south it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Sardinia — the two largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea — and many other smaller islands. The independent states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy, whilst Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland. The territory of Italy covers some and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With 60.4 million inhabitants, it is the sixth most populous country in Europe, and the twenty-third most populous in the world.

http://wn.com/Italy -

Liverpool

Liverpool () is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880. Liverpool is the fourth largest city in the United Kingdom (third largest in England) and has a population of 435,500, and lies at the centre of the wider Liverpool Urban Area, which has a population of 816,216.

http://wn.com/Liverpool -

Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the code name for the operation that launched the invasion of German-occupied western Europe during World War II by Allied forces. The operation commenced on 6 June 1944 with the Normandy landings (commonly known as D-Day). A 12,000-plane airborne assault preceded an amphibious assault involving almost 7,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on 6 June; more than 3 million troops were in France by the end of August.

http://wn.com/Operation_Overlord -

Poland

Poland (), officially the Republic of Poland (Rzeczpospolita Polska), is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north. The total area of Poland is , making it the 69th largest country in the world and the 9th largest in Europe. Poland has a population of over 38 million people, which makes it the 34th most populous country in the world and the sixth most populous member of the European Union, being its most populous Slavic member.

http://wn.com/Poland -

Rome

Rome (; , ; ) is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . In 2006 the population of the metropolitan area was estimated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to have a population of 3.7 million.

http://wn.com/Rome -

Shropshire

Shropshire ( or ; alternatively Salop; abbreviated, in print only, Shrops) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Wales to the west. Shropshire is one of England's most rural and sparsely populated counties with a population density of 91/km2 (337/sq mi). The shire county and its districts were replaced by a unitary authority on 1 April 2009. The borough of Telford and Wrekin, included in Shropshire for ceremonial purposes, has been a unitary authority since 1998.

http://wn.com/Shropshire -

Sorbonne

The Sorbonne (La Sorbonne) is a building of the Latin Quarter, in Paris, France, which has been the historical house of the former University of Paris. It is commonly used to refer to this historic University of Paris or one of its successor institutions (see below), but this is a recent usage, and "Sorbonne" has actually been used with different meanings over the centuries.

http://wn.com/Sorbonne -

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (commonly known as the United Kingdom, the UK, or Britain) is a country and sovereign state located off the northwestern coast of continental Europe. It is an island nation, spanning an archipelago including Great Britain, the northeastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller islands. Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK with a land border with another sovereign state, sharing it with the Republic of Ireland. Apart from this land border, the UK is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea, the English Channel and the Irish Sea. Great Britain is linked to continental Europe by the Channel Tunnel.

http://wn.com/United_Kingdom

- About.com

- acrostic

- anagram

- Anne Boleyn

- arithmetic

- Arthur Wynne

- Atlantic Monthly

- Australia

- Bangalore

- Bengali language

- Bletchley Park

- blindness

- Boston Globe

- Caesar Cipher

- capitalization

- Ch (digraph)

- chessboard

- cipher

- Clare Briggs

- Compass

- Cross Sums

- cross-figure

- Crosswordese

- cryptogram

- Czech language

- Daily Mail

- Daily Telegraph

- Diacritic

- Dutch alphabet

- Dutch language

- Emily Cox (compiler)

- Eugene T. Maleska

- Financial Times

- French language

- GAMES Magazine

- general knowledge

- Georges Perec

- German language

- Germanic umlaut

- Great Britain

- Grid graph

- Hebrew

- Henry Rathvon

- hiragana

- homophone

- Hungarian language

- IJ (letter)

- India

- Irish language

- Ironbridge

- Italian language

- Italy

- Japanese language

- journalist

- kanji

- Kannada language

- katakana

- ktiv haser

- ktiv male

- lakhs

- Latin

- Latticework

- Le Point

- Leonard Dawe

- Liverpool

- ll

- loanword

- logic

- Manny Nosowsky

- Marc Romano

- Margaret Farrar

- Mel Taub

- New York (magazine)

- New York Times

- New York World

- Nice, France

- numbering scheme

- Operation Overlord

- pangram

- Poland

- polyomino

- proper name

- puzzle

- rectangular

- Roger Squires

- Roman numeral

- Roman numerals

- Romanian language

- Rome

- Russian language

- Scrabble

- Scrabble variants

- Senator

- Shropshire

- Simon and Schuster

- Slovak language

- Sorbonne

- Spanish language

- Square (geometry)

- Stephen Sondheim

- Str8ts

- substitution cipher

- Sudoku

- Sunday Express

- symmetry

- The Cross-Wits

- The Daily Telegraph

- The Guardian

- The Independent

- The New Republic

- The New York Times

- The Straight Dope

- The Times

- thousand

- Time Magazine

- United Kingdom

- Upwords

- USA Today

- Usenet

- Visual impairment

- Washington Post

- weather vane

- Will Shortz

- Will Weng

- windsock

- wit

- Wordplay (film)

- Yōon

- ß

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:47

- Published: 16 Sep 2007

- Uploaded: 17 Jun 2011

- Author: mrmatchgame

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:27

- Published: 10 Mar 2006

- Uploaded: 25 Nov 2011

- Author: Dizrythmia

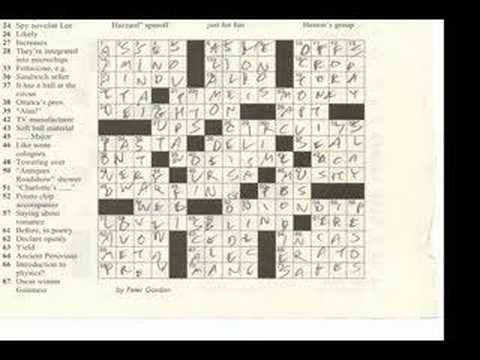

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:41

- Published: 13 Dec 2009

- Uploaded: 20 Apr 2011

- Author: ThePspTester

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:35

- Published: 30 Sep 2008

- Uploaded: 13 Nov 2011

- Author: expertvillage

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:02

- Published: 08 Jun 2010

- Uploaded: 14 Nov 2011

- Author: magicgeekinc

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:58

- Published: 09 Sep 2007

- Uploaded: 04 Nov 2011

- Author: sozoexchange

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:41

- Published: 20 Mar 2008

- Uploaded: 04 Nov 2011

- Author: chrisbarrett

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:32

- Published: 08 Jun 2009

- Uploaded: 25 Aug 2010

- Author: Sterlingpublishing

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:54

- Published: 28 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 03 Jun 2011

- Author: dududueedu

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:25

- Published: 07 Dec 2010

- Uploaded: 17 May 2011

- Author: TheNewYorkTimes

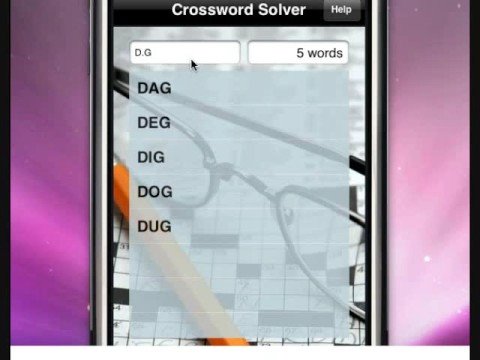

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:10

- Published: 24 Jun 2008

- Uploaded: 18 Apr 2011

- Author: lockergnome

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:15

- Published: 13 Apr 2008

- Uploaded: 28 Nov 2011

- Author: NintendoWorldReport

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:29

- Published: 21 Jul 2009

- Uploaded: 30 Nov 2011

- Author: elleaych2503

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:43

- Published: 27 Oct 2009

- Uploaded: 12 Dec 2011

- Author: ussoccerdotcom

size: 7.3Kb

size: 14.7Kb

-

Philippines floods death toll climbs to over 650

The Observer

Philippines floods death toll climbs to over 650

The Observer

-

'Doomed if You Do, Doomed if You Don't' Leaders and Empires

WorldNews.com

'Doomed if You Do, Doomed if You Don't' Leaders and Empires

WorldNews.com

-

Last US troops leave Iraq, ending 9 years of war

DNA India

Last US troops leave Iraq, ending 9 years of war

DNA India

-

Tropical storm kills scores in Philippines

Gulf News

Tropical storm kills scores in Philippines

Gulf News

-

Last US troops elated to leave Iraq as war ends

Breitbart

Last US troops elated to leave Iraq as war ends

Breitbart

- A. N. Prahlada Rao

- About.com

- acrostic

- anagram

- Anne Boleyn

- arithmetic

- Arthur Wynne

- Atlantic Monthly

- Australia

- Bangalore

- Bengali language

- Bletchley Park

- blindness

- Boston Globe

- Caesar Cipher

- capitalization

- Ch (digraph)

- chessboard

- cipher

- Clare Briggs

- Compass

- Cross Sums

- cross-figure

- Crosswordese

- cryptogram

- Czech language

- Daily Mail

- Daily Telegraph

- Diacritic

- Dutch alphabet

- Dutch language

- Emily Cox (compiler)

- Eugene T. Maleska

- Financial Times

- French language

- GAMES Magazine

- general knowledge

- Georges Perec

- German language

- Germanic umlaut

- Great Britain

- Grid graph

- Hebrew

- Henry Rathvon

- hiragana

- homophone

- Hungarian language

- IJ (letter)

- India

- Irish language

- Ironbridge

- Italian language

- Italy

- Japanese language

- journalist

- kanji

- Kannada language

- katakana

- ktiv haser

- ktiv male

size: 8.5Kb

size: 9.7Kb

size: 10.4Kb

size: 1.5Kb

size: 8.8Kb

A crossword is a word puzzle that normally takes the form of a square or rectangular grid of white and shaded squares. The goal is to fill the white squares with letters, forming words or phrases, by solving clues which lead to the answers. In languages that are written left-to-right, the answer words and phrases are placed in the grid from left to right and from top to bottom. The shaded squares are used to separate the words or phrases.

Squares in which answers begin are usually numbered. The clues are then referred to by these numbers and a direction, for example, "4-Across" or "20-Down". At the end of the clue the total number of letters is sometimes given, depending on the style of puzzle and country of publication. Some crosswords will also indicate the number of words in a given answer, should there be more than one.

Terminology

The horizontal and vertical lines of white cells into which answers are written are commonly called entries or answers. The clues are usually called just that, or sometimes definitions. White cells are sometimes called lights, and the shaded cells are sometimes called darks, blanks, blocks, or just simply black squares or shaded squares.A white cell that is part of two entries (both Across and Down) is called checked, keyed or crossed. A white cell that is part of only one entry is called unchecked, unkeyed or uncrossed.

The creating of crosswords is called cruciverbalism among its practitioners, who are referred to as cruciverbalists, from the Latin for cross and word. Although the terms have existed since the mid 1970s, non-cruciverbalists rarely use them, calling crossword creators constructors or (especially outside the United States) setters or compilers.

Types of grid

Crossword grids such as those appearing in most North American newspapers and magazines feature solid areas of white squares. Every letter is checked, and usually each answer is required to contain at least three letters. In such puzzles shaded squares are traditionally limited to about one-sixth of the design. Crossword grids elsewhere, such as in Britain and Australia, have a lattice-like structure, with a higher percentage of shaded squares, leaving up to half the letters in an answer unchecked. For example, if the top row has an answer running all the way across, there will be no across answers in the second row.

Another tradition in puzzle design (in North America and Britain particularly) is that the grid should have 180-degree rotational symmetry, so that its pattern appears the same if the paper is turned upside down. Most puzzle designs also require that all white cells be orthogonally contiguous (that is, connected in one mass through shared sides, to form a single polyomino).

The design of Japanese crossword grids often follows two additional rules: that shaded cells may not share a side and that the corner squares must be white.

The "Swedish-Style" grid uses no clue numbers - the clues are contained in the cells which would normally be shaded in other countries. Arrows indicate in which direction the clues have to be answered, vertical or horizontal. This style of grid is used in several countries other than Sweden, usually in magazines with pages of A4 or similar size, but also in the daily newspapers, covering entire pages. The grid often has one or more photos replacing a block of squares, as a clue to one answer, for example the name of a pop star, or some kind of rhyme or phrase that can be associated with the photo. These puzzles usually have no symmetry in the grid.

Substantial variants from the usual forms exist. Two of the common ones are barred crosswords, which use bold lines between squares (instead of shaded squares) to separate answers, and circular designs, with answers entered either radially or in concentric circles. Free form crosswords (criss-cross puzzles) have simple designs and are not symmetric. Grids forming shapes other than squares are also occasionally used.

Puzzles are often one of several standard sizes. For example, many weekday puzzles (such as the New York Times crossword) are 15×15 squares, while weekend puzzles may be 21×21, 23×23, or 25×25. The New York Times puzzles also set a common pattern for American crosswords by increasing in difficulty throughout the week: the Monday puzzles are the easiest and the puzzles get harder until Saturday. The larger Sunday puzzle is approximately the same level of difficulty as a weekday-size Thursday puzzle. This has led U.S. solvers to use the day of the week as a shorthand when describing how hard a puzzle is: i.e., an easy puzzle may be referred to as a Monday or Tuesday, a medium-difficulty puzzle as a Wednesday and a truly difficult puzzle as a Saturday.

Typically clues appear outside the grid, divided into an Across list and a Down list; the first cell of each entry contains a number referenced by the clue lists. For example, the answer to a clue labeled "17-Down" is entered with the first letter in the cell numbered "17", proceeding down from there. Numbers are almost never repeated; numbered cells are labeled consecutively, usually from left to right across each row, starting with the top row and proceeding downward. Some Japanese crosswords are numbered from top to bottom down each column, starting with the leftmost column and proceeding right.

Orthography

Capitalization of answer letters is conventionally ignored. This ensures a proper name can have its initial capital letter checked with a non-capitalizable letter in the intersecting clue. Diacritical markings in foreign loanwords are ignored for similar reasons. In languages other than English, the status of diacritics varies according to the orthography of the particular language, thus:

Types of clues

Straight or quick

In some crosswords, often called straight or quick, the clues are usually simple definitions for the answers. Some clues may feature anagrams, and these are usually explicitly described as such. Often, a straight clue is not in itself sufficient to distinguish between several possible answers (often synonyms), and the solver must make use of checks to establish the correct answer with certainty.Crossword clues should be consistent with the solutions. For instance clues and their solutions should always agree in tense and number. If a clue is in the past tense, so is the answer: thus "Traveled on horseback" would be a valid clue for the solution "RODE", but not for "RIDE". Similarly, "Family members" would be a valid clue for "AUNTS" but not "UNCLE". Some clue examples:

In the hands of any but the most skilled constructors, the constraints of the American-style grid (in which every letter is checked) usually require a fair number of answers not to be dictionary words. As a result the following ways to clue abbreviations and other non-words, although they can be found in "straight" British crosswords, are much more common in American ones:

Crossword themes

Many American crossword puzzles contain a "theme" consisting of a number of long entries (generally three to five in a standard 15×15-square "weekday"-size puzzle) that share some relationship, type of pun, or other element in common. As an example, the New York Times crossword of April 26, 2005 by Sarah Keller, edited by Will Shortz, featured five theme entries ending in the different parts of a tree:SQUAREROOT

TABLELEAF

WARDROBETRUNK

BRAINSTEM

BANKBRANCH

The above is an example of a category theme, where the theme elements are all members of the same set. Other types of themes include quote themes, featuring a famous quote broken up into parts to fit in the grid (and usually clued as "Quote, part 1", "Quote, part 2", etc.); rebus themes, where multiple letters or even symbols occupy a single square in the puzzle (e.g., BERMUDAΔ); pun-based themes (perhaps the most common), where all the answers are similar puns; commemorative themes, based on a particular event or person (often published on an appropriate anniversary); and other less common types.

The Simon & Schuster Crossword Puzzle Series has published many unusual themed crosswords. "Rosetta Stone" by Sam Bellotto Jr., incorporated a Caesar Cipher cryptogram as the theme; the key to breaking the cipher was the answer to 1 Across. Another unusual theme required the solver to use the answer to a clue as another clue. The answer to that clue was the real solution.

The first entries

In the 'Quick' crossword in the Daily Telegraph newspaper (Sunday and Daily, UK), it has become a convention also to make the first few words (usually two or three, but can be more) into a phrase. For example, "Dimmer, Allies" would make "Demoralise" or "You, ill, never, walk, alone" would become "You'll never walk alone". This generally aids solvers in that if they have one of the words then they can attempt to guess the phrase. This has also become popular among other British newspapers.

Indirect clues

In many puzzles, some clues involve wordplay and are to be taken metaphorically or in some sense other than their literal meaning, or require some form of lateral thinking. Depending on the puzzle creator or the editor, this might be represented either with a question mark at the end of the clue or with a modifier such as "maybe" or "perhaps". In more difficult puzzles, the indicator may be omitted, increasing ambiguity between a literal meaning and a wordplay meaning. Examples:

Cryptic crosswords

In cryptic crosswords, often called cryptics, the clues are puzzles in themselves. A typical clue contains a definition at the beginning or end of the clue, and wordplay, which describes the word indicated by the definition, and which may not parse logically, but should be grammatical. Cryptics usually give the length of their answers in parentheses after the clue. Certain signs indicate different wordplay. Cryptics have a longer "learning curve" than standard crosswords as learning to interpret the different types of cryptic clues can take some practice. In Great Britain and throughout much of the Commonwealth, cryptics of varying degrees of difficulty are featured in many newspapers.There are several types of wordplay used in cryptics. One is straightforward definition substitution using parts of a word. For example, in one puzzle by Mel Taub, the answer IMPORTANT is given the clue "To bring worker into the country may prove significant". The explanation is that to "import" means "to bring into the country"; the "worker" is a worker ant; and "significant" means "important." Note that in a cryptic clue, there is almost always only one answer that fits both the definition and the wordplay, so that when you see the answer, you know it is the right answer - although it can sometimes be a challenge to figure out why it is the right answer.

A good cryptic clue should provide a fair and exact definition of the answer, while at the same time being deliberately misleading. It is the setter's challenge to mean what he says without necessarily saying what he means - a quandary familiar to those who have enjoyed the writings of Lewis Carroll.

Another type of wordplay used in cryptics is homophones. For example, the clue "A few, we hear, add up (3)" is solved by SUM. The definition is "add up", meaning "totalize". The solver must guess that "we hear" indicates a homophone, and so a homophone of a synonym of "A few" ("SOME") is the answer.

Another wordplay commonly used is the double meaning. For example, "Cat's tongue (7)" is solved by PERSIAN, since this is a type of cat, as well as a tongue, or language.

Cryptics very often include anagrams. The clue "Ned T.'s seal cooked is rather bland (5,4)" is solved by NEEDS SALT. The meaning is "is rather bland", and the word "cooked" is a hint to the solver that this clue is an anagram (the letters have been "cooked", or jumbled up). "Nedtsseal" (ignoring all punctuation, of course) is an anagram for NEEDS SALT. Besides "cooked", other common hints that the clue contains an anagram are words such as "scrambled", "mixed up", "confused", "baked" or "twisted". In answer sheets, an anagram is commonly indicated by an asterisk.

Embedded words are another common trick in cryptics. The clue "Bigotry aside, I'd take him (9)" is solved by APARTHEID. The meaning is "bigotry", and the wordplay explains itself, indicated subtly by the word "take" (since one word "takes" another): "aside" means APART and I'd is simply ID, so APART and ID "take" HE (which is, in cryptic crossword usage, a perfectly good synonym for "him"). The answer could be elucidated as APART(HE)ID.

There is the oft-used hidden clue, where the answer is hidden in the text of the clue itself. For example, "Made a dug-out, buried, and passed away (4)" is solved by DEAD. The answer is written in the clue: "maDE A Dug-out". "Buried" indicates that the answer is embedded within the clue.

There is no end to the wordplay found in cryptic clues. Backwards words can be indicated by words like "climbing", "retreating", or "ascending" (depending on whether it is an across clue or a down clue); letters can be replaced or removed with indicators such as "nothing rather than excellence" (meaning replace E in a word with O); the letter I can be indicated by "me" or "one;" the letter O can be indicated by "nought" or "a ring" (since it visually resembles one); the letter X might be clued as "a cross", or "ten" (as in the Roman numeral), or "an illiterate's signature", or "sounds like your old flame" (homophone for "ex"). "Senselessness" is solved by "e", because "e" is what remains after removing (less) "ness" from "sense".

With the different types of wordplay and definition possibilities, the composer of a cryptic puzzle is presented with many different possible ways to clue a given answer. Most desirable are clues that are clean but deceptive, with a smooth surface reading (that is, the resulting clue looks as natural a phrase as possible). The Usenet newsgroup rec.puzzles.crosswords has a number of clueing competitions where contestants all submit clues for the same word and a judge picks the best one.

In principle, each cryptic clue is usually sufficient to define its answer uniquely, so it should be possible to answer each clue without use of the grid. In practice, the use of checks is an important aid to the solver. (Cryptic crosswords are not to be confused with cryptograms, a different form of puzzle based on a substitution cipher.)

Double clue lists

Sometimes newspapers publish one grid that can be filled by solving either of two lists of clues - usually a straight and a cryptic. The solutions given by the two lists may be different, in which case the solver must decide at the outset which list they are going to follow, or the solutions may be identical, in which case the straight clues offer additional help for a solver having difficulty with the cryptic clues. For example, the solution APARTHEID might be clued as "Bigotry aside, I'd take him (9)" in the cryptic list, and "Racial separation (9)" in the straight list. Usually the straight clue matches the straight part of the cryptic clue, but this is not necessarily the case.Every issue of GAMES Magazine contains a large crossword with a double clue list, under the title The World's Most Ornery Crossword; both lists are straight and arrive at the same solution, but one list is significantly more challenging than the other. The solver is prompted to fold a page in half, showing the grid and the hard clues; the easy clues are tucked inside the fold, to be referenced if the solver gets stuck.

A variant of the double-clue list is commonly called Siamese Twins: two matching grids are provided, and the two clue lists are merged together such that the two clues for each entry are displayed together in random order. Determining which clue is to be applied to which grid is part of the puzzle.

Other clue variations

Any type of puzzle may contain cross-references, where the answer to one clue forms part of another clue, in which it is referred to by number.When an answer is composed of multiple or hyphenated words, some crosswords (especially in Britain) indicate the structure of the answer. For example, "(3,5)" after a clue indicates that the answer is composed of a three-letter word followed by a five-letter word.

Example

Here is a small example of a regular crossword, to illustrate the format:

| width=20 height=20 | 1 | width=20 height=20|| | 2 | ||

| width=20 height=20 | bgcolor=black width=20 height=20 | || | |||

| width=20 height=20 | 3 | width=20 height=20|| | 4 | ||

| bgcolor=black width=20 height=20 | bgcolor=black width=20 height=20 | || | |||

| bgcolor=black width=20 height=20 | bgcolor=black width=20 height=20 | || | 5 |

Across

1. Sheep sound (3) 3. Neither liquid nor gas (5) 5. Humour (3)

Down

1. Road passenger transport (3) 2. Permit (5) 4. Shortened form of Dorothy (3)The solution to this crossword is:

A set of cryptic clues that provide the same answers as above might be:

Across

1. Start of announcement by British Airways sounds woolly? (3) 3. I sold out for real (5) 5. Wilde's intelligence (3)

Down

1. Ferry sees submarine rising (3) 2. Now without its initial after every warrant (5) 4. Do time? There's a point (3)How the clues work:

Across

Down

Major crossword variants

These are common crossword variants that vary more from a regular crossword than just an unusual grid shape or unusual clues; these crossword variants may be based on different solving principles and require a different solving skill set.

Cipher crosswords

Published under various trade names (including Code Breakers, Code Crackers, and Kaidoku), and not to be confused with cryptic crosswords (ciphertext puzzles are commonly known as cryptograms), a cipher crossword replaces the clues for each entry with clues for each white cell of the grid - an integer from 1 to 26 inclusive is printed in the corner of each. The objective, as any other crossword, is to determine the proper letter for each cell; in a cipher crossword, the 26 numbers serve as a cipher for those letters: cells that share matching numbers are filled with matching letters, and no two numbers stand for the same letter. All resultant entries must be valid words. Usually, at least one number's letter is given at the outset. English-language cipher crosswords are nearly always pangrammatic (all letters of the alphabet appear in the solution). As these puzzles are closer to codes than quizzes, they require a different skillset; many basic cryptographic techniques, such as determining likely vowels, are key to solving these. Given their pangrammaticity, a frequent start point is locating where 'Q' and 'U' must appear.

Diagramless crosswords

In a diagramless crossword, often called a diagramless for short or, in the UK, a skeleton crossword or carte blanche, the grid offers overall dimensions, but the locations of most of the clue numbers and shaded squares are unspecified. A solver must deduce not only the answers to individual clues, but how to fit together partially built-up clumps of answers into larger clumps with properly-set shaded squares. Some of these puzzles follow the traditional symmetry rule, others have left-right mirror symmetry, and others have greater levels of symmetry or outlines suggesting other shapes. If the symmetry of the grid is given, the solver can use it to his/her advantage.A variation is the Blankout puzzle in the Daily Mail Weekend magazine. The clues are not individually numbered, but given in terms of the rows and columns of the grid, which has rectangular symmetry. The list of clues gives hints of the locations of some of the shaded squares even before one starts solving them, e.g. there must be a shaded square where a row having no clues intersects a column having no clues.

Fill-in crosswords

A fill-in crossword (also known as crusadex or cruzadex) features a grid and the full list of words to be entered in that grid, but does not give explicit clues for where each word goes. The challenge is figuring out how to integrate the list of words together within the grid so that all intersections of words are valid. Fill-in crosswords may often have longer word length than regular crosswords to make the crossword easier to solve, and symmetry is often disregarded. Fitting together several long words is easier than fitting together several short words because there are fewer possibilities for how the long words intersect together.

Crossnumbers

A crossnumber (also known as a cross-figure) is the numerical analogy of a crossword, in which the solutions to the clues are numbers instead of words. Clues are usually arithmetical expressions, but can also be general knowledge clues to which the answer is a number or year. There are also numerical fill-in crosswords.The Daily Mail Weekend magazine used to feature crossnumbers under the misnomer Number Word. This kind of puzzle should not be confused with a different puzzle that the Daily Mail refers to as Cross Number.

Acrostic puzzles

An acrostic is a type of word puzzle, in eponymous acrostic form, that typically consists of two parts. The first is a set of lettered clues, each of which has numbered blanks representing the letters of the answer. The second part is a long series of numbered blanks and spaces, representing a quotation or other text, into which the answers for the clues fit. In most forms of the puzzle, the first letters of each correct clue answer, read in order from clue A on down the list, will spell out the author of the quote and the title of the work it is taken from; this can be used as an additional solving aid.

Arroword

The arroword is a variant of a crossword that does not have as many black squares as a true crossword, but has arrows inside the grid, with clues preceding the arrows. It has been called the most popular word puzzle in many European countries, and is often called the Scandinavian crossword, as it is believed to have originated in Sweden.

History

The first example of a crossword puzzle appeared on September 14, 1890, in the Italian magazine Il Secolo Illustrato della Domenica. It was designed by Giuseppe Airoldi and titled "Per passare il tempo" ("To pass the time"). Airoldi's puzzle was a four-by-four grid with no shaded squares, but it included horizontal and vertical clues.On December 21, 1913, Arthur Wynne, a journalist from Liverpool, England, published a "word-cross" puzzle in the New York World that embodied most of the features of the genre as we know it. This puzzle is frequently cited as the first crossword puzzle, and Wynne as the inventor. Later, the name of the puzzle was changed to "crossword".

Crossword puzzles became a regular weekly feature in the World, and spread to other newspapers; the Boston Globe, for example was publishing them at least as early as 1917.

By the 1920s, the crossword phenomenon was starting to attract notice. In 1921, the New York Public Library reported that "The latest craze to strike libraries is the crossword puzzle," and complained that when "the puzzle 'fans' swarm to the dictionaries and encyclopedias so as to drive away readers and students who need these books in their daily work, can there be any doubt of the Library's duty to protect its legitimate readers?" In October 1922, newspapers published a comic strip by Clare Briggs entitled "Movie of a Man Doing the Cross-Word Puzzle," with an enthusiast muttering "87 across 'Northern Sea Bird'!!??!?!!? Hm-m-m starts with an 'M', second letter is 'U'... I'll look up all the words starting with an 'M-U...' mus-musi-mur-murd--Hot Dog! Here 'tis! Murre!" In 1923 a humorous squib in The Boston Globe has a wife ordering her husband to run out and "rescue the papers... the part I want is blowing down the street." "What is it you're so keen about?" "The Cross-Word Puzzle. Hurry, please, that's a good boy."

The first book of crossword puzzles appeared in 1924, published by Simon and Schuster. "This odd-looking book with a pencil attached to it" was an instant hit and crossword puzzles became the craze of 1924.

Initially, some viewed the crossword puzzle with alarm, and some expected (even hoped) that it would be a short-lived fad. In 1924, The New York Times complained of the "sinful waste in the utterly futile finding of words the letters of which will fit into a prearranged pattern, more or less complex. This is not a game at all, and it hardly can be called a sport... [solvers] get nothing out of it except a primitive form of mental exercise, and success or failure in any given attempt is equally irrelevant to mental development." A clergyman called the working of crossword puzzles "the mark of a childish mentality" and said "There is no use for persons to pretend that working one of the puzzles carries any intellectual value with it.". In 1925 Time Magazine noted that nine Manhattan dailies and fourteen other big newspapers were carrying crosswords, and quoted opposing views as to whether "This crossword craze will positively end by June!" or "The crossword puzzle is here to stay!" In 1925 the New York Times noted, with approval, a scathing critique of crosswords by The New Republic; but concluded that "Fortunately, the question of whether the puzzles are beneficial or harmful is in no urgent need of an answer. The craze evidently is dying out fast and in a few months it will be forgotten." and in 1929 declared "The cross-word puzzle, it seems, has gone the way of all fads...." In 1930 a correspondent noted that "Together with The Times of London, yours is the only journal of prominence that has never succumbed to the lure of the cross-word puzzle" and said that "The craze—the fad—stage has passed, but there are still people numbering it to the millions who look for their daily cross-word puzzle as regularly as for the weather predictions." The New York Times, however, was not to publish a crossword puzzle until 1942.

The term crossword first appeared in a dictionary in 1930.

Today, there are many popular crosswords distributed in American newspapers and online. The most prestigious (and among the most difficult to solve) are the New York Times puzzles. The first editor of the New York Times crossword was Margaret Farrar, who was editor from 1942 to 1969. She was succeeded by Will Weng, who was succeeded by Eugene T. Maleska. Since 1993, they have been edited by Will Shortz, the fourth crossword editor in Times. In 1978 Shortz founded and still directs the annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament.

Simon and Schuster continues to publish the Crossword Puzzle Book Series books that it began in 1924, currently under the editorship of John M. Samson. The original series ended in 2007 after 258 volumes. Since 2008, these books are now in the Mega series, appearing three times per year and each featuring 300 puzzles.

The British cryptic crossword was imported to the US in 1968 by composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim in New York magazine. Until 2006, the Atlantic Monthly regularly featured a cryptic crossword "puzzler" by Emily Cox and Henry Rathvon, which combines cryptic clues with diabolically ingenious variations on the construction of the puzzle itself. In both cases, no two puzzles are alike in construction, and the intent of the puzzle authors is to entertain with novelty, not to establish new variations of the crossword genre.

In the United Kingdom, the Sunday Express was the first newspaper to publish a crossword on November 2, 1924, a Wynne puzzle adapted for the UK. The first crossword in Britain, according to Tony Augarde in his "Oxford Guide to Word Games" (1984), was in "Pearson's Magazine" for February 1922.

Crossword puzzles in World War II

In 1944 Allied security officers were disturbed by the appearance, in a series of crosswords in The Daily Telegraph, of words that were secret code names for military operations planned as part of Operation Overlord. "Utah" (the code name for one of the landing sites) appeared in a puzzle on May 2, 1944. Subsequent puzzles included the landing site "Omaha" and "Mulberry"; the secret artificial harbours.On June 2, four days before the invasion, the puzzle included both "Neptune" (the naval operations plan) and "Overlord". The author of the puzzles, a schoolteacher named Leonard Dawe, was interviewed. The investigators concluded that the appearance of the words was not an attempt to pass messages. According to a former crossword editor of The Daily Telegraph, in 1984 a former student of Dawe's claimed that he had picked up the words from soldiers' conversations around the army camps, and included them when helping Dawe to choose words to fill crossword grids. Marc Romano, author of the book Crossworld: One Man's Journey into America's Crossword Obsession, gives a number of reasons why he believes the story is implausible.

Some cryptologists for Bletchley Park were selected after doing well in a crossword-solving competition.

Crossword records

According to Guinness Records, May 15, 2007, the most prolific crossword compiler is Roger Squires of Ironbridge, Shropshire, UK. On May 14, 2007 he published his 66,666th crossword, equivalent to 2 million clues. He is one of only four setters to have provided cryptic puzzles to The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, the Financial Times and The Independent. He also holds the record for the longest word ever used in a published crossword - the 58-letter Welsh town Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch clued as an anagram.Enthusiasts have compiled a number of record-setting achievements for the New York Times crossword, the most prestigious American-style crossword:

The fewest shaded squares in a 15x15 American crossword are 18 (leaving 207 white spaces), first set by the August 22, 2008 Times crossword by Kevin G. Der, and tied by the August 7, 2010 Times crossword by Joe Krozel.

Crosswords in non-English languages

Although the crossword is an English-language invention and most common in English-speaking countries, other countries have crosswords in their respective languages.French-language crosswords are smaller than English-language ones, and not necessarily square: usually 8–13 rows and columns, totaling 81–130 squares. They need not be symmetric and two-letter words are allowed, unlike in most English-language puzzles. Compilers strive to minimize use of shaded squares. 10% is typical; Georges Perec compiled many 9×9 grids for Le Point with four or even three . Rather than numbering the individual clues, the rows and columns are numbered as on a chessboard. All clues for a given row or column are listed, against its number, as separate sentences. This is similar to the notation used in the aforementioned Daily Mail Blankout puzzles.

In Italy, crosswords are usually oblong and larger than French ones, 13x21 being a common size. As in France, they usually are not symmetrical; two-letter words are allowed; and the number of shaded squares is minimized. Nouns (including surnames) and the infinitive or past participle of verbs are allowed, as are abbreviations; in larger crosswords, it is customary to put at the center of the grid phrases made of two to four words, or forenames and surnames. A variant of Italian crosswords does not use shaded squares: words are delimited by thickening the grid. Another variant starts with a blank grid: the solver must insert both the answers and the shaded squares, and Across and Down clues are either ordered by row and column or not ordered at all.

Particularly curious is the Japanese language crossword; due to the writing system, one syllable (typically katakana) is entered into each white cell of the grid rather than one letter, resulting in the typical solving grid seeming rather small in comparison to those of other languages. Any second Yōon character is treated as a full syllable and is rarely written with a smaller character. Even cipher crosswords have a Japanese equivalent, although pangrammaticity does not apply. The crossword with kanji to fill in are also produced, but in far smaller number as it takes far more effort to construct one. Despite having three writing forms, hiragana, katakana and kanji, they are rarely mixed in a crossword puzzle.

In Poland, crosswords typically use British-style grids, but some do not have shaded cells. Shaded cells are often replaced by boxes with clues - such crosswords are called Swedish puzzles or Swedish-style crosswords. In a vast majority of Polish crosswords, nouns are the only allowed words. Modern Hebrew is normally written with only the consonants; vowels are either understood, or entered as diacritical marks. This can lead to ambiguities in the entry of some words, and compilers generally specify that answers are to be entered in ktiv male (with some vowels) or ktiv haser (without vowels). Further, since Hebrew is written from right to left, but Roman numerals are used and written from left to right, there can be an ambiguity in the description of lengths of entries, particularly for multi-word phrases. Different compilers and publications use differing conventions for both of these issues.

In India a setter named A. N. Prahlada Rao from Bangalore has composed some 25,000 crossword puzzles in the language Kannada, including 6,500 crosswords based on films made in Kannada, with a total of 6,40,000 (six hundred forty thousand or six lakhs and forty thousand) clues. He has contributed crosswords to 24 periodicals including 3 dailies. He has created crosswords with themes ranging from Film to Mythology to Crime to Food to the works of famous Kannada novelists. A five volume set of his puzzles was released in February 2008 . Bengali is also well known for its crossword puzzles. Crosswords are published regularly in almost all the Bengali dailies and periodicals. The grid system is quite similar to the British style and two-letter words are usually not allowed.

Notation

A notation has evolved to allow crosswords to be rendered compactly, and enjoyed by the blind or partially sighted.It consists of giving the locations of the shaded squares in each row as letters (A=1,B=2, etc.), e.g. for the example crossword above:

# D E # B D E # # A B D # A B

Although the numbering scheme could be consistently applied from this information, it is customary to quote the starting square of each clue in (number-letter) format.

See also

References

The Crossword Obsession by Coral Amende ISBN 0-425-18157-X Crossworld by Marc Romano ISBN 0-7679-1757-X

External links

Category:British inventions Category:Leisure activities Category:NP-complete problems Category:1913 introductions * Category:Italian inventions

ar:كلمات متقاطعة ay:Kitjata arunaka bn:শব্দছক zh-min-nan:Si̍p-jī-gú bs:Križaljka bg:Кръстословица ca:Mots encreuats cv:Сăмах каçмăш ceb:Pulongbay cs:Křížovka da:Krydsordsopgave de:Kreuzworträtsel el:Σταυρόλεξο es:Crucigrama eo:Krucvortenigmo eu:Hitz gurutzatuak fa:جدول کلمات متقاطع fr:Mots croisés ga:Crosfhocal gl:Encrucillado ko:십자말 hy:Խաչբառ hi:वर्ग पहेली hr:Križaljka id:Teka-teki silang it:Parole crociate he:תשבץ kn:ಪದಬಂಧ ka:კროსვორდი la:Crucigramma lv:Krustvārdu mīkla lt:Kryžiažodis hu:Keresztrejtvény nl:Kruiswoordpuzzel ja:クロスワードパズル no:Kryssord nn:Kryssord pl:Krzyżówka (zagadka) pt:Palavras cruzadas ro:Cuvinte încrucișate ru:Кроссворд sq:Fjalëkryqi simple:Crossword sl:Križanka sr:Укрштене речи sh:Križaljka fi:Sanaristikko sv:Korsord uk:Кросворд zh:填字游戏This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.