The Tuareg (also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym Imuhagh) are a Berber people with a traditionally nomadic pastoralist lifestyle. They are the principal inhabitants of the Saharan interior of North Africa.[2][3]

The Tuareg language, or languages, have an estimated 1.2 million speakers. About half this number is accounted for by speakers of the Eastern dialect (Tamajaq, Tawallammat).[1] Most Tuareg live in the Saharan parts of Niger and Mali but, being nomadic, there is constant movement across national borders, and small groups of Tuareg are also found in southeastern Algeria, southwestern Libya and northern Burkina Faso, and a small community in northern Nigeria.[4]

The name Tuareg is derived from Targa, the Berber name of Libya's Fezzan province. The name Tuareg thus in origin designated the inhabitants of Fezzan from the perspective of the Berbers living closer to the Mediterranean coast, and was adopted from them into English, French and German during the colonial period. The Berber noun targa means "drainage channel" and by extension "arable land, garden". It designated the Wadi al-Haya area between Sabha and Ubari and is rendered in Arabic as bilad al-khayr "good land". There is a widespread Arabic folk etymology of the name, connecting tawariq "abandoned [by God]", reflecting the religious disapproval of residual animist practice among the Tuareg by orthodox Muslims.

The name of the Tuareg for themselves is Imuhagh (Imazaghan or Imashaghen, Imazighan). The term for a Tuareg man is Amajagh (var. Amashegh, Amahagh), the term for a woman Tamajaq (var. Tamasheq, Tamahaq, Timajaghen). The spelling variants given reflect the variety of the Tuareg dialects, but they all reflect the same linguistic root, expressing the notion of "freemen", strictly only referring to the Tuareg "nobility", to the exclusion of the artisan client castes and slaves. Another self-designation of more recent origin is linguistic, Kel Tamasheq or Kel Tamajaq (Neo-Tifinagh ⴾⴻⵍ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵌⴰⵆ) "Speakers of Tamasheq".

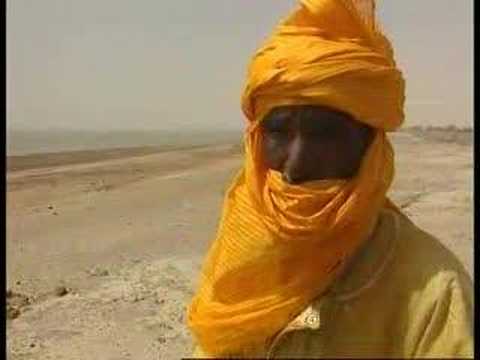

Also encountered in ethnographic literature of the early 20th century is the name Kel Tagelmust "People of the Veil"[5] and "the Blue People" (for the indigo colour of their veils).[citation needed]

Areas where significant numbers of Tuareg live

The Tuareg people inhabit a large area, covering almost all the middle and western Sahara and the north-central Sahel. In Tuareg terms, the Sahara is not one desert but many, so they call it Tinariwen ("the Deserts"). Among the many deserts in Africa, there is the true desert Ténéré. Other deserts are more and less arid, flat and mountainous: Adrar, Tagant, Tawat (Touat) Tanezrouft, Adghagh n Fughas, Tamasna, Azawagh, Adar, Damargu, Tagama, Manga, Ayr, Tarramit (Termit), Kawar, Djado, Tadmait, Admer, Igharghar, Ahaggar, Tassili n'Ajjer, Tadrart, Idhan, Tanghart, Fezzan, Tibesti, Kalansho, Libyan Desert, etc. While there is little conflict about the driest parts of Tuareg territory, many of the water sources and pastures they need for cattle breeding get fenced off by absentee landlords, impoverishing some Tuareg communities. There is also an unresolved land conflict about many stretches of farm land just south of the Sahara. Tuareg often also claim ownership over these lands and over the crop and property of the impoverished Rimaite-people, farming them.[citation needed]

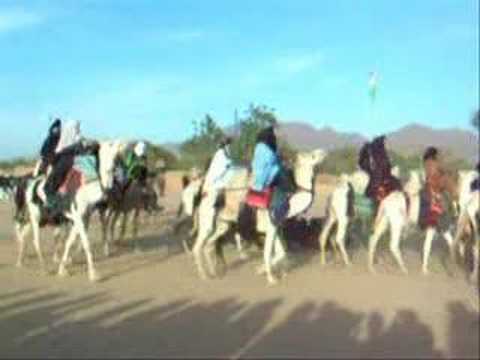

The Tuareg adopted camel nomadism, along with its distinctive form of social organization, from camel-herding Arabs about two thousand years ago, when the camel was introduced to the Sahara from Arabia. Since that time, they had operated the trans-Saharan caravan trade connecting the great cities on the southern edge of the Sahara via five desert trade routes to the northern (Mediterranean) coast of Africa.[3] The Tuareg once took captives, either for trade and sale, or for domestic labor purposes. Those who were not sold became assimilated into the Tuareg community. Slaves and herdsmen formed a component of the division of labor in camel nomadism.

They expanded southward from the Tafilalt region into the Sahel under their legendary queen Tin Hinan, who is assumed to have lived in the 4th or 5th century.[6] Tin Hinan is credited in Tuareg lore with uniting the ancestral tribes and founding the unique culture that continues to our time. At Abalessa, a grave traditionally held to be hers has been scientifically studied.[citation needed]

In the late 19th century, the Tuareg resisted the French colonial invasion of their Central Saharan homelands. Tuareg broadswords were no match for the more advanced weapons of French squadrons. After numerous massacres on both sides,[7] the Tuareg were subdued and required to sign treaties in Mali 1905 and Niger 1917. In southern Morocco and Algeria, the French met some of the strongest resistance from the Ahaggar Tuareg. Their Amenokal, traditional chief Moussa ag Amastan, fought numerous battles in defense of the region. Finally, Tuareg territories were taken under French governance, and their confederations were largely dismantled and reorganized.

Before French colonization, the Tuareg were organized into loose confederations, each consisting of a dozen or so tribes. Each of the main groups had a traditional leader called Amenokal, along with an assembly of tribal chiefs (imɣaran, singular amɣar). The groups were the Kel Ahaggar, Kel Ajjer, Kel Ayr, Adrar n Fughas, Iwəlləmədan, and Kel Gres.

At the turn of the 19th century, the Tuareg territory was organized into confederations, each ruled by a supreme Chief (Amenokal), along with a counsel of elders from each tribe. These confederations are sometimes called "Drum Groups" after the Amenokal's symbol of authority, a drum. Clan (Tewsit) elders, called Imegharan (wisemen), are chosen to assist the chief of the confederation. Historically, there are seven recent major confederations:

- Kel Ajjer or Azjar: center is the oasis of Aghat (Ghat).

- Kel Ahaggar, in Ahaggar mountains.

- Kel Adagh, or Kel Assuk: Kidal, and Tin Buktu

- Iwillimmidan Kel Ataram, or Western Iwillimmidan: Ménaka, and Azawagh region (Mali)

- Iwillimmidan Kel Denneg, or Eastern Iwillimmidan: Tchin-Tabaraden, Abalagh, Teliya Azawagh (Niger).

- Kel Ayr: Assodé, Agadez, In Gal, Timia and Ifrwan.

- Kel Gres: Zinder and Tanut (Tanout) and south into northern Nigeria.

- Kel Owey: Air Massif, seasonally south to Tessaoua (Niger)

When African countries achieved widespread independence in the 1960s, the traditional Tuareg territory was divided among a number of modern nations: Niger, Mali, Algeria, Morocco, Libya, and Burkina Faso. Competition for resources in the Sahel have since led to conflicts between the Tuareg and neighboring African groups, especially after political disruption and economic constraints following French colonization and independence. There have been tight restrictions placed on nomadization because of high population growth. Desertification is exacerbated by human activity i.e.; exploitation of resources and the increased firewood needs of growing cities. Some Tuareg are therefore experimenting with farming; some have been forced to abandon herding and seek jobs in towns and cities.

In Mali, a Tuareg uprising resurfaced in the Adrar N'Fughas mountains in the 1960s, following Mali's independence. Several Tuareg joined, including some from the Adrar des Iforas in northeastern Mali. The 1960s' rebellion was a fight between a group of Tuareg and the newly independent state of Mali. The Malian Army suppressed the revolt. Resentment among the Tuareg fueled the second uprising.

This second (or third) uprising was in May 1990. At this time, in the aftermath of a clash between government soldiers and Tuareg outside a prison in Tchin-Tabaraden, Niger, Tuareg in both Mali and Niger claimed autonomy for their traditional homeland: (Ténéré, capital Agadez, in Niger and the Azawad and Kidal regions of Mali). Deadly clashes between Tuareg fighters (with leaders such as Mano Dayak) and the military of both countries followed, with deaths numbering well into the thousands. Negotiations initiated by France and Algeria led to peace agreements (January 11, 1992 in Mali and 1995 in Niger). Both agreements called for decentralization of national power and guaranteed the integration of Tuareg resistance fighters into the countries' respective national armies.

Major fighting between the Tuareg resistance and government security forces ended after the 1995 and 1996 agreements. As of 2004, sporadic fighting continued in Niger between government forces and Tuareg groups struggling for independence. In 2007, a new surge in violence occurred.

Since the development of Berberism in North Africa in the 1990s, there has also been a Tuareg ethnic revival. A Tuareg ethnic flag in red, white, and blue has been presented,[by whom?][year needed][8] and there is increased use of Neo-Tifinagh, a script derived from the historical Berber script used by the Numidians in pre-Roman times.[citation needed]

Tuareg from the Hoggar, Algeria

Traditionally, Tuareg society is hierarchical, with nobility and vassals. Each Tuareg clan (tawshet) is made up of several family groups, led by their collective chiefs, the amghar. A series of tribes tawsheten may bond together under an Amenokal, forming a Kel clan confederation. Tuareg self identification is related only to their specific Kel, which means "those of". E.g. Kel Dinnig (those of the east), Kel Ataram (those of the west).

The work of pastoralism was specialized according to social class. Tels are ruled by the imúšaɣ (Imajaghan, The Proud and Free) nobility, warrior-aristocrats who organized group defense, livestock raids, and the long-distance caravan trade. Below them were a number of specialised métier castes. The ímɣad (Imghad, singular Amghid), the second rank of Tuareg society, were free vassal-herdsmen and warriors, who pastured and tended most of the confederation's livestock. Formerly enslaved vassals of specific Imajaghan, they are said by tradition to be descended from nobility in the distant past, and thus maintain a degree of social distance from lower orders. Traditionally, some merchant castes had a higher status than all but the nobility among their more settled compatriots to the south. With time, the difference between the two castes has eroded in some places, following the economic fortunes of the two groups.

Imajaghan have traditionally disdained certain types of labor and prided themselves in their warrior skills. The existence of lower servile and semi-servile classes has allowed for the development of highly ritualised poetic, sport, and courtship traditions among the Imajaghan. Following colonial subjection, independence, and the famines of the 1970s and 1980s, noble classes have more and more been forced to abandon their caste differences. They have taken on labor and lifestyles they might traditionally have rejected.

After the adoption of Islam, a separate class of religious clerics, the Ineslemen or marabouts, also became integral to Tuareg social structure. Following the decimation of many clans' noble Imajaghan caste in the colonial wars of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Ineslemen gained leadership in some clans, despite their often servile origins. Traditionally Ineslemen clans were not armed. They provided spiritual guidance for the nobility, and received protection and alms in return.

Inhædˤæn (Inadan), were a blacksmith-client caste who fabricated and repaired the saddles, tools, household equipment and other material needs of the community. In most communities, the Inadin were freedmen drawn from the servile éklan caste and not considered outsiders by the other classes.

The Tuareg once held slaves (éklan / Ikelan in Tamasheq, Bouzou in Hausa, Bella in Songhai).

Tuareg moved south on the continent in the 11th century AD, taking slaves from other groups. These éklan once formed a distinct social class in Tuareg society. Some Tuareg noble and vassal men married slaves, and their children became freemen. Eklan formed distinct sub-communities; they were a class held in an inherited serf-like condition, common among societies in precolonial West Africa.[citation needed]

When French colonial governments were established, they passed legislation to abolish slavery, but did not enforce it. Some commentators believe the French interest was directed more at dismantling the traditional Tuareg political economy, which depended on slave labor for herding, than at freeing the slaves.[9][10][11][12] Historian Martin Klein reports that there was a large scale attempt by French West African authorities to liberate slaves and other bonded castes in Tuareg areas following the 1914–1916 Firouan revolt.[13] Despite this, French officials following the Second World War reported there were some 50,000 "Bella" under direct control of Tuareg masters in the Gao–Timbuktu areas of French Soudan alone.[14] This was at least four decades after French declarations of mass freedom had happened in other areas of the colony. In 1946, a series of mass desertions of Tuareg slaves and bonded communities began in Nioro and later in Menaka, quickly spreading along the Niger River valley.[15] In the first decade of the 20th century, French administrators in southern Tuareg areas of French Soudan estimated "free" to "servile" Tuareg populations at ratios of 1 to 8 or 9.[16] At the same time the servile "rimaibe" population of the Masina Fulbe, roughly equivalent to the Bella, made up between 70% to 80% of the Fulbe population, while servile Songhai groups around Gao made up some 2/3 to 3/4 of the total Songhai population.[16] Klein concludes that roughly 50% of the population of French Soudan at the beginning of the 20th century were in some servile or slave relationship.[16]

While post-independence states have sought to outlaw slavery, results have been mixed. Traditional caste relationships have continued in many places, including the institution of slavery.[17][18][19][20][21][22] According to the Travel Channel show, Bob Geldof in Africa, the descendants of those slaves known as the Bella are still slaves in all but name. In Niger, where the practice of slavery was outlawed in 2003, a study found that almost 8% of the population are still enslaved.[23]

Tuareg nomads in the south of Algeria

The Tuareg are "largely matrilineal".[24][25][26] Tuareg women have high status compared with their Arab counterparts; for further information see the Tuareg section of the Matrilineality article.

Many Tuareg today are either settled agriculturalists or nomadic cattle breeders, though there are also blacksmiths and caravan leaders.

In Tuareg society women do not traditionally wear the veil, whereas men do.[24][26] The most famous Tuareg symbol is the Tagelmust (also called éghéwed), referred to as a Cheche (pronounced "Shesh"), an often indigo blue-colored veil called Alasho. The men's facial covering originates from the belief that such action wards off evil spirits. It may have related instrumentally from the need for protection from the harsh desert sands as well. It is a firmly established tradition, as is the wearing of amulets containing sacred objects and from recently also verses from the Qur'an. Taking on the veil is associated with the rite of passage to manhood; men begin wearing a veil when they reach maturity. The veil usually conceals their face, excluding their eyes and the top of the nose.

The Tuareg are sometimes[year needed] called the "Blue People" because the indigo pigment in the cloth of their traditional robes and turbans stained their skin dark blue.[by whom?][citation needed] The traditional indigo turban is still preferred for celebrations, and generally Tuareg wear clothing and turbans in a variety of colors.

Taguella is a flat bread made from millet(a grain) which is cooked on charcoals in the sand and eaten with a heavy sauce. Millet porridge is a staple much like ugali and fufu. Millet is boiled with water to make a pap and eaten with milk or a heavy sauce. Common dairy foods are goat's and camel's milk, as well as cheese and yogurt made from them. Eghajira is a thick beverage drunk with a ladle. It is made by pounding millet, goat cheese, dates, milk and sugar and is served on festivals like Eid ul-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. A popular tea, gunpowder tea, is poured three times in and out of a tea pot with mint and sugar into tiny glasses.

The Tuareg speak Tamajaq/Tamasheq/Tamahaq, the language is called Tamasheq by western Tuareg in Mali, Tamahaq among Algerian and Libyan Tuareg, and Tamajaq in the Azawagh and Aïr regions, Niger.

French missionary Charles de Foucauld famously compiled a dictionary of the Tuareg language.

Traditionally Tuareg practiced Animism, then with the onset of Arabs into North Africa, Islam came in and the Tuareg travelled South and mixed their animistic beliefs with Islam.[27]

Much Tuareg art is in the form of jewelry, leather and metal saddle decorations called trik, and finely crafted swords. The Inadan community makes traditional handicrafts. Among their products are tanaghilt or zakkat (the 'Agadez Cross' or 'Croix d'Agadez'); the Tuareg Takoba, many gold and silver-made necklaces called 'Takaza'; and earrings called 'Tizabaten'.

The clear desert skies allowed the Tuareg to be keen observers. Tuareg stars and constellations include:

While living quarters are progressively changing to adapt to a more sedentary lifestyle, Tuareg groups are well known for their nomadic architecture (tents). There are several documented styles, some covered with animal skin, some with mats. The style tends to vary by location or subgroup.[28] Because the tent is considered to be under the ownership of a married women (and significantly, built during the marriage ceremony), sedentary dwellings generally belong to men, reflecting a patriarchal shift in power dynamics. Current documentation suggests a negotiation of common practice in which a woman's tent is set up in the courtyard of her husband's house.[29]

|

|

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. Consider associating this request with a WikiProject. (March 2011) |

Old legend says Tuareg once lived in grottoes, akazam, and then they lived in foliage beds made on the top acacia trees, tasagesaget, to avoid numerous wild animal during old times and even to this day to escape from mosquitoes.

Other kinds of traditional housing include:

- ahaket: Tuareg goatskin red tent

- tafala: a shade made of millet sticks

- akarban also called takabart: temporary hat for winter

- ategham: summer hat

- taghazamt: adobe house for long stay

- ahaket: a dome-shaped house made of mats for the dry season and square shaped roof with holes to prevent hot air

- takoba: 1 meter long straight sword

- allagh: 2 meter long lance

- agher: 1.50 meter high shield

- tagheda: small and sharp assegai

- taganze: leather covered-wooden bow

- amur: wooden arrow

- sheru: long dagger

- taburek: wooden stick

- alakkud or abartak: riding crop

In 2007, Stanford's Cantor Arts Center opened an exhibition, "Art of Being Tuareg: Sahara Nomads in a Modern World", the first such exhibit in the United States. It was curated by Tom Seligman, director of the center. He had first spent time with the Tuareg in 1971 when he traveled through the Sahara after serving in the Peace Corps. The exhibition included crafted and adorned functional objects such as camel saddles, tents, bags, swords, amulets, cushions, dresses, earrings, spoons and drums.[30] The exhibition also was shown at the University of California, Los Angeles Fowler Museum in Los Angeles and the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C.

Throughout history, the Tuareg were renowned and respected warriors. Their decline as a military might came with the introduction of firearms, weapons which the Tuareg did not possess. The Tuareg warrior attire consisted of a takoba (sword), allagh (lance) and aghar (shield) made of antelope's skin.

Traditional Tuareg music has two major components: the moncord violin anzad played often during night parties and a small tambour covered with goatskin called tende, performed during camel and horse races, and other festivities. Traditional songs called Asak and Tisiway (poems) are sung by women and men during feasts and social occasions. Another popular Tuareg musical genre is takamba, characteristic for its Afro percussions.

Vocal music

- tisiway: poems

- tasikisikit: songs performed by women, accompanied by tende, men on camel back turn around

- asak: songs accompanied by anzad monocord violin.

- tahengemmit: slow songs sung by elder men

Tinariwen, taken at the Nice Jazz Festival in France

Children and youth music

- Bellulla songs made by children playing with the lips

- Fadangama small monocord instrument for children

- Odili flute made from trunk of sorghum

- Gidga small wooden instrument with irons sticks to make strident sounds

Dance

- tagest: dance made while seated, moving the head, the hands and the shoulders.

- ewegh: strong dance performed by men, in couples and groups.

- agabas: dance for modern ishumar guitars: women and men in groups.

In the 1980s rebel fighters founded Tinariwen, a Tuareg band that fuses electric guitars and indigenous musical styles. Tinariwen is one of the best known and authentic Tuareg bands. Especially in areas that were cut off during the Tuareg rebellion (e.g., Adrar des Iforas), they were practically the only music available, which made them locally famous and their songs/lyrics (e.g. Abaraybone, ...) are well known by the locals. They released their first CD in 2000, and toured in Europe and the United States in 2004. Tuareg guitar groups that followed in their path include Group Inerane and Group Bombino. The Niger-based band Etran Finatawa combines Tuareg and Wodaabe members, playing a combination of traditional instruments and electric guitars.

Many music groups emerged after the 1980s cultural revival. Among the Tartit, Imaran and known artists are: Abdallah Oumbadougou from Ayr, Baly Othmany of Djanet.

Traditional music

- Majila Ag Khamed Ahmad, singer Asak (vocal music), of Aduk, Niger

- Almuntaha female Anzad (Tuareg violin) player, of Aduk, Niger

- Ajju female Anzad (Tuareg violin) player, of Agadez, Niger

- Islaman singer, genre Asak (vocal music), of Abalagh, Niger

- Tambatan singer, genre Asak (vocal music), Tchin-Tabaraden, Niger

- Alghadawiat female Anzad (Tuareg violin) player, of Akoubounou, Niger

- Taghdu female Anzad (Tuareg violin) player, of Aduk, Niger

Ishumar music or Teshumara music style

- In Tayaden singer and guitar player, Adagh

- Abareybon singer and guitar player, Tinariwen group, Adagh

- Kiddu Ag Hossad singer and guitar player, Adagh

- Baly Othmani singer, luth player, Djanet, Azjar

- Abdalla Ag Umbadugu, singer, Takrist N'Akal group, Ayr

- Hasso Ag Akotey, singer, Ayr

The Desert Festival in Mali's Timbuktu provides one opportunity to see Tuareg culture and dance and hear their music.

Tuareg celebration of Sbiba

Other festivals include:

Tuareg traditional games and plays include:

- Tiddas, played with small stones and sticks.

- Kelmutan: consists of singing and touching each person's leg, where the ends, that person is out: the last person loses the game.

- Temse: comic game try to make the other team laugh and you win.

- Izagag, played with small stones or dried fruits.

- Iswa, played by picking up stones while throwing another stone.

- Melghas, children hide themselves and another tries to find and touch them before they reach the well and drink.

- Tabillant, traditional Tuareg wrestling

- Alamom, wrestling while running

- Solagh, another type of wrestling

- Tammazaga or Tammalagha, race on camel back

- Takket, singing and playing all night.

- Sellenduq one person to be a jackal and try to touch the others who escape running.

- Takadant, children try to imagine what the others are thinking.

- Tabakoni: clown with a goatskin mask to amuse children.

- Abarad Iqquran: small dressed wooden puppet that tells stories and make people laugh.

- Maja Gel Gel: one person tries to touch all people standing, to avoid this sit down.

- Bellus: everyone run not to be touched by the one who plays.

- Tamammalt: pass a burning stick, when its blown off in ones hands tells who's the lover.

- Ideblan: game with girl prepare food and go search for water and milk and fruits.

- Seqqetu: play with girls to learn how to build tents, look after babies made of clay.

- Mifa Mifa: beauty contest, girls and boys best dressed.

- Taghmart: children pass from house to house singing to get presents: dates, sugar etc.

- Melan Melan: try to find a riddle

- Tawaya: play with the round fruit calotropis or a piece of cloth.

- Abanaban: try to find people while eyes are shut.(blind mans buff)

- Shishagheren, writing the name of one's lover to see if this person brings good luck.

- Taqqanen, telling devinettes and enigmas.

- Maru Maru, young people mime how the tribe works.

Tuareg selling crafts to tourists in the

Hoggar (Algeria)

Tuareg are distinguished in their native language as the Imouhar, meaning the free people; the overlap of meaning has increased local cultural nationalism. The Tuareg are a pastoral people, having an economy based on livestock breeding, trading, and agriculture.[3]

Caravan Trade

Since Prehistoric times Tuareg peoples: the Garamantes have been organising caravans for trading across the Sahara desert. The caravan is called in Tamashek: Tarakaft or Taghlamt and also Azalay.

These caravans used first oxen, horses and later camels as a means of transportation, here differents types of caravans:

- caravans transporting food: dates, millet, dryed meat, dryed Tuareg cheese, butter etc.

- caravans transporting garments, alasho indigo turbans, leather products, ostrich feathers,

- caravans transporting salt: salt caravans used for exchange against other products.

- caravans transporting nothing but made to sell and buy camels.

Salt mines or salines in the desert.

A contemporary variant is occurring in northern Niger, in a traditionally Tuareg territory that comprises most of the uranium-rich land of the country. The central government in Niamey has shown itself unwilling to cede control of the highly profitable mining to indigenous clans. The Tuareg are determined not to relinquish the prospect of substantial economic benefit. The French government has independently tried to defend a French firm, Areva, established in Niger for fifty years and now mining the massive Imouraren deposit.

Additional complaints against Areva are that it is: "...plundering...the natural resources and [draining] the fossil deposits. It is undoubtedly an ecological catastrophe".[citation needed] These mines yield uranium ores, which are then processed to produce yellowcake, crucial to the nuclear power industry (as well as aspirational nuclear powers). In 2007, some Tuareg people in Niger allied themselves with the Niger Movement for Justice (MNJ), a rebel group operating in the north of the country. During 2004–2007, U.S. Special Forces teams trained Tuareg units of the Nigerien Army in the Sahel region as part of the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership. Some of these trainees are reported to have fought in the 2007 rebellion within the MNJ. The goal of these Tuareg appears to be economic and political control of ancestral lands, rather than operating from religious and political ideologies.[citation needed]

Despite the Sahara's erratic and unpredictable rainfall patterns, the Tuareg have managed to survive in the hostile desert environment for centuries. Over recent years however, depletion of water by the uranium exploitation process combined with the effects of climate change are threatening their ability to subsist. Uranium mining has diminished and degraded Tuareg grazing lands. Not only does the mining industry produce radioactive waste that can contaminate crucial sources of ground water resulting in cancer, stillbirths, and genetic defects but it also uses up huge quantities of water in a region where water is already scarce. This is exacerbated by the increased rate of desertification thought to be the result of global warming. Lack of water forces the Tuareg to compete with southern farming communities for scarce resources and this has led to tensions and clashes between these communities. The precise levels of environmental and social impact of the mining industry have proved difficult to monitor due to governmental obstruction.

- ^ a b Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

- ^ "Q&A: Tuareg unrest". BBC. 7 September 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6982266.stm. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "Who are the Tuareg?". Smithsonian Institution. http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/tuareg/who.html. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ "The total Tuareg population is well above one million individuals." Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie, Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world, Elsevier, 2008, ISBN 9780080877747, p. 152.

- ^ See Rodd 1926.

- ^ Brett, Michael; Elizabeth Fentress The Berbers Wiley Blackwell 1997 ISBN 978-0631207672 p. 208

- ^ "Charles de Foucauld - Sera béatifié à l'automne 2005". http://www.africamission-mafr.org/foucauld2.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ "Berbers: Armed movements". Fotw.us. http://www.fotw.us/flags/xb%5Earm.html#pro. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ Martin A. Klein. Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa. (African Studies, number 94.) New York: Cambridge University Press. (1998) ISBN 9780521596787

- ^ Edouard Bernus. "Les palmeraies de l'Aïr", Revue de l'Occident Musulman et de la Méditerranée, 11, (1972) pp. 37–50.

- ^ Frederick Brusberg. "Production and Exchange in the Saharan Air", Current Anthropology, Vol. 26, No. 3. (Jun., 1985), pp. 394–395. Field research on the economics of the Aouderas valley, 1984.

- ^ Michael J. Mortimore. "The Changing Resources of Sedentary Communities in Air, Southern Sahara", Geographical Review, Vol. 62, No. 1. (Jan., 1972), pp. 71–91.

- ^ Klein (1998) pp.111–140

- ^ Klein (1998) p. 234

- ^ Klein (1998) pp. 234–251

- ^ a b c Klein (1998) "Appendix I:How Many Slaves?" pp. 252–263

- ^ Anti-Slavery International & Association Timidira, Galy kadir Abdelkader, ed. Niger: Slavery in Historical, Legal and Contemporary Perspectives. March 2004

- ^ Hilary Andersson, "Born to be a slave in Niger", BBC Africa, Niger

- ^ "Kayaking to Timbuktu, Writer Sees Slave Trade, More", National Geographic.

- ^ "The Shackles of Slavery in Niger". ABC News. 2005-06-03. http://abcnews.go.com/International/Story?id=813618&page=1. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ "Niger: Slavery - an unbroken chain". Irinnews.org. http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=53497. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ "On the way to freedom, Niger's slaves stuck in limbo", Christian Science Monitor

- ^ "The Shackles of Slavery in Niger", ABC News

- ^ a b Haven, Cynthia (2007-05-23). "A Stanford Univ. news article of 23May07". News.stanford.edu. http://news.stanford.edu/pr/2007/pr-tuareg-052307.html. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ Spain, Daphne (1992). Gendered Spaces. Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2012-1, p. 57.

- ^ a b Murphy, Robert F. (Apr1966). Untitled review of a 1963 major ethnographic study of the Tuareg. American Anthropologist, New Series, 68 (1966), No.2, 554-556.

- ^ Schlichte, Klaus (1994). "Is Ethnicity a Cause of War?". Peace Review (London: Routledge) 6 (1): 59–65. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a787823151. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Prussin, Labelle "African Nomadic Architecture" 1995.

- ^ Rasmussen, Susan "The Tent as Cultural Symbol and Field Site: Social and Symbolic Space, "Topos", and Authority in a Tuareg Community", Anthropological Quarterly, Vol 69, 1996.

- ^ "First Exhibition of Tuareg Art and Culture in America Appears at Stanford Before Traveling to the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art", Cantor Arts Center

- Ghoubeid Alojaly, Karl Prasse, Ghabdouane Mohamed, Dictionnaire touareg-français, Copenhague, Museum Tusculanum, 2003 (2 vols., 1031 p.) - ISBN 87-7289-844-5

- Francis James Rennell Rodd, People of the veil. Being an account of the habits, organisation and history of the wandering Tuareg tribes which inhabit the mountains of Air or Asben in the Central Sahara, London, MacMillan & Co., 1926 (repr. Oosterhout, N.B., Anthropological Publications, 1966)

- Heath Jeffrey 2005: A Grammar of Tamashek (Tuareg of Mali). New York: Mouton de Gruyer. Mouton Grammar Library, 35. ISBN 3-11-018484-2

- Rando et al. (1998) "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of northwest African populations reveals genetic exchanges with European, near-eastern, and sub-Saharan populations". Annals of Human Genetics 62(6): 531-50; Watson et al. (1996) mtDNA sequence diversity in Africa. American Journal of Human Genetics 59(2): 437–44; Salas et al. (2002) "The Making of the African mtDNA Landscape". American Journal of Human Genetics 71: 1082–1111. These are good sources for information on the genetic heritage of the Tuareg and their relatedness to other populations.

- Edmond Bernus, "Les Touareg", pp. 162–171 in Vallées du Niger, Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993.

- Andre Bourgeot, Les Sociétés Touarègues, Nomadisme, Identité, Résistances, Paris: Karthala, 1995.

- Hélène Claudot-Hawad, ed., "Touregs: Exil et Résistance". Révue du Monde Musulman et de la Méiterranée, No. 57, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1991.

- Claudot-Hawad, Touaregs, Portrait en Fragments, Aix-en-Provence: Edisud, 1993.

- Hélène and Hawad Claudot-Hawad, "Touaregs: Voix Solitaires sous l'Horizon Confisque", Ethnies-Documents No. 20-21, Hiver, 1996.

- Mano Dayak, Touareg: La Tragedie, Paris: Éditions Lattes, 1992.

- Sylvie Ramir, Les Pistes de l'Oubli: Touaregs au Niger, Paris: éditions du Felin, 1991.

![Entrance to Kidal. The name of the town is written in Traditional Tifinagh (ⴾⴸⵍ) and Latin script. Tifinagh (ⵜⵉⴼⵉⵏⴰⵖ in Neo-Tifinagh, Tifinaɣ in Berber Latin alphabet, pronounced [tifinaɣ]) is an alphabetic script used by some Berber peoples, notably the Tuareg, to write their language Entrance to Kidal. The name of the town is written in Traditional Tifinagh (ⴾⴸⵍ) and Latin script. Tifinagh (ⵜⵉⴼⵉⵏⴰⵖ in Neo-Tifinagh, Tifinaɣ in Berber Latin alphabet, pronounced [tifinaɣ]) is an alphabetic script used by some Berber peoples, notably the Tuareg, to write their language](http://web.archive.org./web/20121018043922im_/http://cdn4.wn.com/pd/db/25/234a8a922b0613f542368eb6bca2_small.jpg)