IMAGING CONFLICT RESOLUTION

A Conversation with

The advantage of neuroscience is being able to look under the hood and see the mechanisms that actually create the thoughts and the behaviors that create and perpetuate conflict. Seems like it ought to be useful. That's the question that I'm asking myself right now, can science in general, or neuroscience in particular, be used to understand what drives conflict, what prevents reconciliation, why some interventions work for some people some of the time, and how to make and evaluate better ones.

REBECCA SAXE is an Associate Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience in the department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT. She is also an associate member of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research. She is known for her research on the neural basis of social cognition.

Rebecca Saxe's Edge Bio Page

IMAGING CONFLICT RESOLUTION

[REBECCA SAXE:] One of the questions I'm asking myself from my work is the question I've always been asking myself: how is it going to be useful? I have an idea for how the kind of work I do could be useful, but I'm not at all sure this is possible, or possible in my lifetime. The idea has a big version and a little version. The big version has to do with self-knowledge and understanding ourselves. The big idea is that neuroscience is a kind of self-knowledge. It's a way of understanding our minds and our behaviors. If we get it right, if we really come to understand our brains, we will understand ourselves, we will be better at predicting our behaviors in contexts and in ways that really matter. In trying to run a society, you need to know how the elements of it would work, just as much as to run a machine you need to know how the physical elements work.

Our society is built of a bunch of minds trying to work together. It seems like having better, more scientific understanding of the mind is the only possible way to have a better functioning society. That's the big idea, which seems quite ludicrous. Then the question is to try to work it out in an example. The example is almost as ludicrous. The example I'm working on right now is conflict and conflict resolution: how to make groups of people that are suspicious of one another and on the brink of war with one another more tolerant, more accepting, more forgiving, and more capable of working together. There are a bunch of ways that the kind of neuroscience I've done could help in that context.

J. CRAIG VENTER: THE BIOLOGICAL-DIGITAL CONVERTER, OR, BIOLOGY AT THE SPEED OF LIGHT @ THE EDGE DINNER IN TURIN

Ginevra Elkann e Carlo Antonelli

hanno il piacere di invitarla all'

Edge Dinner

in onore di John Brockman, J. Craig Venter e Brian Eno

martedì 10 luglio

ore 19.30 aperitivo

ore 20.30 cena

Ristorante Del Cambio – Piazza Carignano, 2 – Torino

Introduction

by John Brockman

It was a perfect trifecta of invitations.

1. An invitation from Craig Venter to join him in Dublin for "one of the landmark events of 20th Century science" in which he had been asked, to celebrate and reinterpret for the 21st Century Erwin Schrödinger's seminal lecture, entitled "What is Life?"delivered in 1943 at Trinity College, Dublin. The then Prime Minister, Éamon de Valera, attended the lecture along with his cabinet.

Venter, at the forefront of recent advances in genetics and synthetic biology, was asked to reconsider the fundamental question posed by Schrödinger 70 years ago. Would I join him for the lecture in Examination Hall, Trinity College, and Dublin on Thursday, July 12th? Having been on the road with Venter in Europe and elsewhere, I didn't hesitate. "Maybe", I replied.

2. "I'm a deity in Torino", said a bemused Brian Eno. The artist-musician was talking about expectations for his new exhibition, an installation of clouds of music at the Royal Palace in Venaria Reale, just outside Turin, one of Italy's magnificent public places. "When I gave the public lecture," Eno said, "thousands of people wanted to get in.Eno is one of the most interesting intellectuals I know, is and always worth my time, so spending a couple of days with him in Italy, was an attractive proposition. We had recently collaborated on an Edge dinner at his London studio in Notting Hill. Since then, I learned some more about Eno's background in music and art when I happened to watch a documentary about U2's early days in Germany. In it, Bono explains that he, and many musicians in his world, started as artists, and Eno was their teacher.

3. "Yes, you should go to Torino", said the curator and Edge collaborator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Co-Director of London's Serpentine Gallery. "It is very glamorous. And Edge has a big following there. Whatever Ginevra has in mind, it will be elegant". He was talking about Ginevra Elkann, a film producer, as well as President of Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, the modern museum that houses part of her grandparent's permanent collection which was designed for the Agnelli family by the architect Renzo Piano. Perched on the roof of the gigantic building that once housed the Fiat plant in Turin, the museum is surrounded by a race track for testing the automobiles manufactured for Fiat and Ferrari by Elkann's late grandfather, Gianni Agnelli, the biggest industrialist in Italian history. The museum, in addition to its permanent collection, is primarily devoted to exhibits of personal collections of interesting people from the artist Damian Hirst, to the dealer Bruno Bischofberger, to Jean Pigozzi, the owner of the largest collection of African art and a long-time Edgie.

It was at the DLD Conference in Munich last January that I met Elkann and Carlo Antonelli, editor-in-chief of the Italian edition of Wired. "Come to Torino," they said. We'll host an Edge evening, an Edge dinner. "Everyone" will come, not just from Torino, but from Rome and from Milan as well.

So, I told Venter I would go to Dublin to hear his talk if he would come to Turin with me and do a trial run at an Edge dinner two days prior. Eno agreed to stay on for the event. Elkann and Antonelli created a marvelous ambience of people and place that made for a memorable event, particularly due to Venter's provocative talk on new developments in synthetic genomics research, which set the stage for his historic lecture in Dublin later in the week.

—JB

WHAT IS LIFE? A 21st CENTURY PERSPECTIVE

Introduction

by John Brockman

Several weeks ago, I received the following message from Craig Venter:

"John,

"I would like to extend an invitation for you to join me in Dublin, Ireland the week of July 10 during which one of the landmark events of 20th Century science will be celebrated and reinterpreted for the 21st Century as part of the Science in the City program of Euroscience Open Forum 2012 (ESOF 2012). This unique event will connect an important episode in Ireland's scientific heritage with the frontier of contemporary research.

"In February 1943 one of the most distinguished scientists of the 20th Century, Erwin Schrödinger, delivered a seminal lecture, entitled 'What is Life?', under the auspices of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, in Trinity College, Dublin. The then Prime Minister, Éamon de Valera, attended the lecture and an account of it featured in the 5 April 1943, issue of Time magazine.

"The lecture presented far-sighted ideas on how hereditary information could be encoded in a chemical structure (aperiodic crystal) in living cells. Schrödinger's book (1944) of the same title is considered to be a scientific classic. The book was cited by Crick and Watson as one of the inspirations which ultimately led them to unravel the structure of DNA in 1953, a breakthrough which won them the Nobel prize. Recent advances in genetics and synthetic biology mean that it is now timely to reconsider the fundamental question posed by Schrödinger 70 years ago. I have been asked to revisit Schrödinger's question and will do so in a lecture entitled "What is Life? A 21st century perspective"; on the evening of Thursday, July 12 at the Examination Hall in Trinity College Dublin."

Never one to turn down an interesting invitation, I was able to organize an interesting week beginning with an Edge Dinner in Turin, in honor of Venter, Brian Eno and myself, where Venter, in an after-dinner talk, began to publicly present some of the new ideas he would flesh out in his Dublin talk.

Then on to Dublin, where I sat in the front row at Examination Hall next to Jim Watson and Irish Prime Minister (the "Taoiseach) Enda Kenny for Venter's lecture. At it's conclusion, the two legendary scientists, Watson and Venter, shook hands on stage, as Watson congratulated Venter for "a beautiful lecture". Schrödinger to Watson to Venter: It was an historic moment.

Listen and watch carefully.

—JB

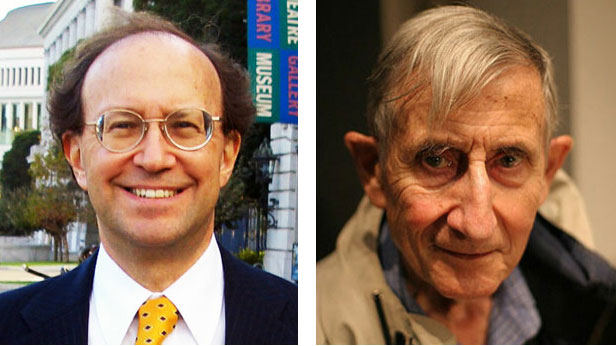

James Watson congratulates Craig Venter at conclusion of the lecture

A NEW KIND OF SOCIO-INSPIRED TECHNOLOGY

There's a new kind of socio-inspired technology coming up, now. Society has many wonderful self-organization mechanisms that we can learn from, such as trust, reputation, culture. If we can learn how to implement that in our technological system, that is worth a lot of money; billions of dollars, actually. We think this is the next step after bio-inspired technology.

PROFESSOR DIRK HELBING is Chair of Sociology, in particular of Modeling and Simulation, at ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and the Scientific Coordinator of the FuturICT Flagship Proposal.

A NEW KIND OF SOCIO-INSPIRED TECHNOLOGY

[DIRK HELBING:] People are sometimes asking me what would we do if we had one billion euro for research. We have been thinking about that, actually, for a while. We thought we know so much about our universe and about our physical world, but we don't understand all the problems on earth, so we should really turn around this man on the moon mission and basically take the shuttle down to the earth in order to see what is going on there. The big unexplored continent in science is actually social science, so we really need to understand much better the principles that make our society work well, and socially interactive systems.

Our future information society will be characterized by computers that behave like humans in many respects. In ten years from now, we will have computers as powerful as our brain, and that will really fundamentally change society. Many professional jobs will be done much better by computers. How will that change society? How will that change business? What impacts does that have for science, actually?

THE FALSE ALLURE OF GROUP SELECTION

An Edge Original Essay

I am often asked whether I agree with the new group selectionists, and the questioners are always surprised when I say I do not. After all, group selection sounds like a reasonable extension of evolutionary theory and a plausible explanation of the social nature of humans. Also, the group selectionists tend to declare victory, and write as if their theory has already superseded a narrow, reductionist dogma that selection acts only at the level of genes. In this essay, I'll explain why I think that this reasonableness is an illusion. The more carefully you think about group selection, the less sense it makes, and the more poorly it fits the facts of human psychology and history.

THE REALITY CLUB: Stewart Brand, Daniel Everett, David C. Queller, Daniel C. Dennett, Herbert Gintis, Harvey Whitehouse & Ryan McKay, Peter J. Richerson, Jerry Coyne, Michael Hochberg, Robert Boyd & Sarah Mathew, Max Krasnow & Andrew Delton,Nicolas Baumard, Jonathan Haidt, David Sloan Wilson, Michael E. Price, Joseph Henrich, Randolph M. Nesse, Richard Dawkins, Helena Cronin, John Tooby.

Group selection has become a scientific dust bunny, a hairy blob in which anything having to do with "groups" clings to anything having to do with "selection." The problem with scientific dust bunnies is not just that they sow confusion; … the apparent plausibility of one restricted version of "group selection" often bleeds outwards to a motley collection of other, long-discredited versions. The problem is that it also obfuscates evolutionary theory by blurring genes, individuals, and groups as equivalent levels in a hierarchy of selectional units; ... this is not how natural selection, analyzed as a mechanistic process, really works. Most importantly, it has placed blinkers on psychological understanding by seducing many people into simply equating morality and culture with group selection, oblivious to alternatives that are theoretically deeper and empirically more realistic.

STEVEN PINKER is a Harvard College Professor and Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology; Harvard University. Author, The Better Angels Of Our Nature: How Violence Has Declined, The Language Instinct, and How the Mind Works.

[photo credit: Max Gerber]

THE FALSE ALLURE OF GROUP SELECTION

Human beings live in groups, are affected by the fortunes of their groups, and sometimes make sacrifices that benefit their groups. Does this mean that the human brain has been shaped by natural selection to promote the welfare of the group in competition with other groups, even when it damages the welfare of the person and his or her kin? If so, does the theory of natural selection have to be revamped to designate "groups" as units of selection, analogous to the role played in the theory by genes?

Several scientists whom I greatly respect have said so in prominent places. And they have gone on to use the theory of group selection to make eye-opening claims about the human condition.[1] They have claimed that human morailty, particularly our willingness to engage in acts of altruism, can be explained as an adaptation to group-against-group competition. As E. O. Wilson explains, "In a group, selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals. But, groups of altruistic individuals beat groups of selfish individuals." They have proposed that group selection can explain the mystery of religion, because a shared belief in supernatural beings can foster group cohesion. They suggest that evolution has equipped humans to solve tragedies of the commons (also known as collective action dilemmas and public goods games), in which actions that benefit the individual may harm the community; familiar examples include overfishing, highway congestion, tax evasion, and carbon emissions. And they have drawn normative moral and political conclusions from these scientific beliefs, such as that we should recognize the wisdom behind conservative values, like religiosity, patriotism, and puritanism, and that we should valorize a communitarian loyalty and sacrifice for the good of the group over an every-man-for-himself individualism.

SUMMER READING 2012

INNOVATION ON THE EDGES

.jpg)

Today, what you want is you want to have resilience and agility, and you want to be able to participate in, and interact with the disruptive things. Everybody loves the word 'disruptive innovation.' Well, how does, and where does disruptive innovation happen? It doesn't happen in the big planned R&D labs; it happens on the edges of the network. Most important ideas, especially in the consumer Internet space, but more and more now in other things like hardware and biotech, you're finding it happening around the edges.

JOI ITO is MIT Media Lab Director and a leading thinker and writer on innovation, global technology policy, and the role of the Internet in transforming society in substantial and positive ways. A vocal advocate of emergent democracy, privacy, and Internet freedom, Ito is board chair (and former CEO) of Creative Commons, and sits on the Boards of The New York Times Company, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Knight Foundation, Mozilla Foundation, WITNESS, and Global Voices.

INNOVATION ON THE EDGES

[JOI ITO:] I grew up in Japan part of my life, and we were surrounded by Buddhists. If you read some of the interesting books from the Dalai Lama talking about happiness, there's definitely a difference in the way that Buddhists think about happiness, the world and how it works, versus the West. I think that a lot of science and technology has this somewhat Western view, which is how do you control nature, how do you triumph over nature? Even if you look at the gardens in Europe, a lot of it is about look at what we made this hedge do.

What's really interesting and important to think about is, as we start to realize that the world is complex, and as the science that we use starts to become complex and, Timothy Leary used this quote, "Newton's laws work well when things are normal sized, when they're moving at a normal speed." You can predict the motion of objects using Newton's laws in most circumstances, but when things start to get really fast, really big, and really complex, you find out that Newton's laws are actually local ordinances, and there's a bunch of other stuff that comes into play.

ON "ITERATED PRISONER’S DILEMMA CONTAINS STRATEGIES THAT DOMINATE ANY EVOLUTIONARY OPPONENT"

"Robert Axelrod's 1980 tournaments of iterated prisoner's dilemma strategies have been condensed into the slogan, Don't be too clever, don't be unfair. Press and Dyson have shown that cleverness and unfairness triumph after all." — William Poundstone, from his Commentary

Introduction

In January I had the occasion to spend sometime in Munich with Freeman Dyson who informed me about a paper on "The Prisoner's Dilemma" he had co-authored with William H. Press, and he then briefly sketched out some of its ramifications. He indicated that they had come up with something new, a way to win the game. It's simple, he said. The winning strategy: go to lunch. And, he added, the only way to trump this strategy is to come up with a new theory of mind. I tried to go deeper but, he said, "I don't really understand game theory, I just did the math. This is really Bill Press's work."

The highly technical paper, "Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma contains strategies that dominate any evolutionary opponent" by William H. Press and Freeman J. Dyson has now been published in PNAS (May 22, 2012), which was followed by a PNAS Commentary by Alexander Stewart and Joshua Plotkin of the Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, entitled "Extortion and cooperation in the Prisoner’s Dilemma" (June 18, 2012). Here's the Abstract of the paper:

"The two-player Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma game is a model for both sentient and evolutionary behaviors, especially including the emergence of cooperation. It is generally assumed that there exists no simple ultimatum strategy whereby one player can enforce a unilateral claim to an unfair share of rewards. Here, we show that such strategies unexpectedly do exist. In particular, a player X who is witting of these strategies can (i) deterministically set her opponent Y’s score, independently of his strategy or response, or (ii) enforce an extortionate linear relation between her and his scores. Against such a player, an evolutionary player’s best response is to accede to the extortion. Only a player with a theory of mind about his opponent can do better, in which case Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma is an Ultimatum Game."

Edge asked William Poundstone, author of the book The Prisoner's Dilemma, to explain the paper in non-technical terms. In his Commentary below, he writes:

"Robert Axelrod's 1980 tournaments of iterated prisoner's dilemma strategies have been condensed into the slogan, Don't be too clever, don't be unfair. Press and Dyson have shown that cleverness and unfairness triumph after all."

Also below are responses by William Press to Poundstone and by Freeman Dyson to Stewart and Plotkin.

To kick off a Reality Club conversation, mathematician Karl Sigmund at University of Vienna, and biological mathematician Martin Nowak of Harvard, two pioneers of evolutionary game theory, comment below.

— JB

THE REALITY CLUB: Karl Sigmund & Martin Nowak

THE ADOLESCENT BRAIN

"The idea that the brain is somehow fixed in early childhood, which was an idea that was very strongly believed up until fairly recently, is completely wrong. There's no evidence that the brain is somehow set and can't change after early childhood. In fact, it goes through this very large development throughout adolescence and right into the 20s and 30s, and even after that it's plastic forever, the plasticity is a baseline state, no matter how old you are. That has implications for things like intervention programs and educational programs for teenagers."

Introduction

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore is a leading social neuroscientist of adolescent development. She has reawakened research interest into the puberty period by focusing on social cognition and its neural underpinnings. Part of her question is whether adolescence involves egocentrism, as many popular conceptions suggest, since this is testable.

Part of her originality is to remind us of the remarkable changes in brain structure during adolescence, given the traditional focus of developmental psychology is on early childhood. Using a range of techniques, including conducting elegant MRI studies, she illuminates a neglected phase of cognitive development. Given that the sex steroid hormones are produced in higher quantities during this period, her research opens up interesting questions about whether the changes in the brain are driven by the endocrine system, or by changing social experience, or an interaction of these factors.

—Simon Baron-Cohen

SARAH-JAYNE BLAKEMORE is a Royal Society University Research Fellow and Full Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, UK. Blakemore’s research centers on the development of social cognition and executive function in the typically developing adolescent brain, using a variety of behavioral and neuroimaging methods.

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore's Edge Bio

SIMON BARON-COHEN, Psychologist, is Professor of Developmental Psychopathology and Director of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University, a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge; Author, The Science of Evil; The Essential Difference.

Simon Baron-Cohen's Edge Bio

This Will Make You Smarter New Scientific Concepts To Improve Your Thinking.edited By John Brockman. Harper Perennial, Paper, $15.99. [8.5.12]

Delving into this book is like overhearing a heated conversation in a lab. It captures the preoccupations of top scientists and offers a rare chance to discover big ideas before they hit the mainstream.

This Will Make You Smarter New Scientific Concepts To Improve Your Thinking.edited By John Brockman. Harper Perennial, Paper, $15.99. [8.5.12]

Delving into this book is like overhearing a heated conversation in a lab. It captures the preoccupations of top scientists and offers a rare chance to discover big ideas before they hit the mainstream.

"The Man Who Runs The World's Smartest Website" (in The Observer)

Since the mid-1960s John Brockman has been at the cutting edge of ideas. He is a passionate advocate of both science and the arts, and his website Edge is a salon for the world's finest minds

To say that John Brockman is a literary agent is like saying that David Hockney is a photographer. For while it's true that Hockney has indeed made astonishingly creative use of photography, and Brockman is indeed a successful literary agent who represents an enviable stable of high-profile scientists and communicators, in both cases the description rather understates the reality. More accurate ways of describing Brockman would be to say that he is a "cultural impresario" or, as his friend Stewart Brand puts it, an "intellectual enzyme". (Brand goes on helpfully to explain that an enzyme is "a biological catalyst – an adroit enabler of otherwise impossible things".)

The first thing you notice about Brockman, though, is the interesting way he bridges CP Snow's "Two Cultures" – the parallel universes of the arts and the sciences. When profilers ask him for pictures, one he often sends shows him with Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan, no less. Or shots of the billboard photographs of his head that were used to publicise an eminently forgettable 1968 movie, . But he's also one of the few people around who can phone Nobel laureates in science with a good chance that they will take the call. . . . [Download Guardian Digital pdf of print edition] [Photo Credit: Peter Yang]

RECENT CONVERSATIONS AT EDGE.ORG

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

THIS WILL MAKE YOU SMARTER: New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking Foreword By David Brooks Edited by John Brockman [2.17.12] IMAGING CONFLICT RESOLUTION A Conversation With Rebecca Saxe [8.9.12] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

LATEST NEWS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THIS WILL MAKE YOU SMARTER

New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking.Edited by John Brockman.

Harper Perennial, paper, $15.99.

Jascha Hoffman, New York Times - Sunday Book Review

[8.5.12]

Delving into this book is like overhearing a heated conversation in a lab. It captures the preoccupations of top scientists and offers a rare chance to discover big ideas before they hit the mainstream. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CRAIG VENTER: DNA BY E-MAIL AND IN 3D FOR TAILORED VACCINES

GABRIEL BECCARIA, LA STAMPA

[7.12.12]

We will decipher DNA ship at lightning speed around the world, where it is necessary. Yesterday evening you could hear these prophecies by Craig Venter in Turin, in an event known as the "Edge Dinner", one of the many dinners between scientists and assorted guests organized around the world by John Brockman, the literary agent American stars of science. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOW TO CURE A PHANTOM LIMB. In the past, scientists often presented ideas in books that were understandable by non-specialists.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, Il Sole 24 ORE - Domenica

[7.1.12]

Think of the Origin of Species and the emotional expressions of Darwin, in fact almost all his books, to those of Galileo an In the last century that the custom seemed to be lost, but it has been given new life by a literary agent, John Brockman, and authors such as Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, Francis Crick, Eric Kandel, Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

WHERE THE DIALOGUE BETWEEN ART AND SCIENCE WAS BORN.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, LA REPUBLICA

[6.22.12]

Cage was preparing dinner and discussed.Those evenings were great opportunities for cultural enrichment. It was there that I heard for the first time of McLuhan. Unlike writers, scholars and artists were very interested in the sciences. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MYSTERY OF BIG DATA’S PARALLEL UNIVERSE BRINGS FEAR, AND A THRILL

By Denis Overbye, THE NEW YORK TIMES

[6.5.12]

It is perhaps time to be afraid. Very afraid, suggests the science historian George Dyson, author of a recent biography of John von Neumann, one of the inventors of the digital computer. In “A Universe of Self-Replicating Code,” a conversation published on the Web site Edge, Mr. Dyson says that the world’s bank of digital information, growing at a rate of roughly five trillion bits a second, constitutes a parallel universe of numbers and codes and viruses with its own “physics” and “... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE REAL LASTING POWER OF TWO: True Einsteinian, Jobs-like innovation comes from your solar plexus; from your gut; from your soul

Shoba Narayan, Live Mint & The Wall Street Journal

[6.1.12]

Where do cool ideas come from? Every year, the online salon Edge.org poses one question and gets a bunch of smart people to answer it. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THIS WILL MAKE YOU SMARTER might just be the most brilliantly, profoundly, intellectually challenging book you'll ever read. It takes your mind to some extraordinary places, challenging your imagination with ideas that can and will take your breath away.

Kunal Bambawale, Neon Tommy (USC Annnberg Digital News)

[4.21.12]

These are people who live at the outermost frontiers of human knowledge -- thinkers who spend their lives using what we do know to discover what we don't. Their words are inspiring, comforting and occasionally alarming. Their wisdom is great. But their tone is never arrogant or elitist. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

DIGITALLY ALTERED (Review of the Week) The debate surrounding the cyber world's impact on our cognitive processes is delivered from all sides in a finely constructed anthology.

Conrad Walters, Sydney Morning Herald

[4.30.12]

Note, he asked contributors how the internet has changed the way ''you'' - not ''we'' - think. Brockman's aim is not treatises. He wants personal responses, and to a satisfying degree he gets them. ... The question for his 2010 edition (even the internet has not sped the arrival of this print-format book to our shores) produces little consensus. This proves a central strength. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

EVENTS

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| INFORMATION GARDENS Edge ~ Sepentine Gallery Special Events [10.16.11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Master Class 2011: The Science of Human Nature Master Classes [7.15.11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edge@DLD 2011 Special Events [1.23.11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Annual Question

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE DEEP, ELEGANT, OR BEAUTIFUL EXPLANATION?

[2012]

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE DEEP, ELEGANT, OR BEAUTIFUL EXPLANATION?

[2012]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

WHAT SCIENTIFIC CONCEPT WOULD IMPROVE EVERYBODY'S COGNITIVE TOOLKIT?

[2011]

WHAT SCIENTIFIC CONCEPT WOULD IMPROVE EVERYBODY'S COGNITIVE TOOLKIT?

[2011]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GET EDGE.ORG BY EMAIL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unsubscribe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||