- Order:

- Duration: 2:49

- Published: 17 Nov 2007

- Uploaded: 11 Dec 2010

- Author: thimblekg

The earliest known thimble was Roman and was found at Pompeii. Made of bronze, its creation has been dated to the 1st century AD. A second Roman thimble was found at Verulamium, present day St Albans, in the UK and can be viewed in the museum there.

According to the United Kingdom Detector Finds Database , thimbles dating to the 10th century have been found in England, and thimbles were in widespread use there by the 14th century. Although there are isolated examples of thimbles made of precious metals—Elizabeth I is said to have given one of her ladies-in-waiting a thimble set with precious stones—the vast majority of metal thimbles were made of brass. Medieval thimbles were either cast brass or made from hammered sheet. Early centers of thimble production were those places known for brass-working, starting with Nuremberg in the 15th century, and moving to Holland by the 17th.

In 1693, a Dutch thimble manufacturer named John Lofting established a thimble manufactory in Islington, in London, England, expanding British thimble production to new heights. He later moved his mill to Buckinghamshire to take advantage of water-powered production, resulting in a capacity to produce more than two million thimbles per year. By the end of the 18th century, thimble making had moved to Birmingham, and shifted to the "deep drawing" method of manufacture, which alternated hammering of sheet metals with annealing, and produced a thinner-skinned thimble with a taller shape. At the same time, cheaper sources of silver from the Americas made silver thimbles a popular item for the first time.

Thimbles are usually made from metal, leather, rubber, and wood, and even glass or china. Early thimbles were sometimes made from whale bone, horn, or ivory. Natural sources were also utilized such as Connemara marble, bog oak, or mother of pearl. Rarer works from thimble makers utilized diamonds, sapphires, or rubies.

Advanced thimblemakers enhanced thimbles with semi-precious stones to adorn the apex or along the outer rim. Cabochon adornments are sometimes made of cinnabar, agate, moonstone, or amber. Thimble artists would also utilize enameling, or the Guilloché techniques advanced by Peter Carl Fabergé.

Originally, thimbles were used solely for pushing a needle through fabric or leather as it was being sewn. Since then, however, they have gained many other uses. In the 19th century they were used to measure spirits, which brought rise to the phrase "just a thimbleful". Prostitutes used them in the practice of thimble-knocking where they would tap on a window to announce their presence. Thimble-knocking also refers to the practice of Victorian schoolmistresses who would tap on the heads of unruly pupils with dames thimbles.

Before the 18th century the small dimples on the outside of a thimble were made by hand punching, but in the middle of that century, a machine was invented to do the job. If one finds a thimble with an irregular pattern of dimples, it was likely made before the 1850s. Another consequence of the mechanization of thimble production is that the shape and the thickness of the metal changed. Early thimbles tend to be quite thick and to have a pronounced dome on the top. The metal on later ones is thinner and the top is flatter.

Collecting thimbles became popular in the UK when many companies made special thimbles to commemorate the Great Exhibition held in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London.

In the 19th century, many thimbles were made from silver; however, it was found that silver is too soft a metal and can be easily punctured by most needles. Charles Horner solved the problem by creating thimbles consisting of a steel core covered inside and out by silver, so that they retained their aesthetics but were now more practical and durable. He called his thimble the Dorcas, and these are now popular with collectors. There is a small display of his work in Bankfield Museum, Halifax, England.

Early American thimbles made of whale bone or tooth featuring miniature scrimshaw designs are considered valuable collectibles. Such rare thimbles are prominently featured in a number of New England Whaling Museums.

During the First World War, silver thimbles were collected from "those who had nothing to give" by the British government and melted down to buy hospital equipment. In the 1930s and 40s red-topped thimbles were used for advertising. Leaving a sandalwood thimble in a fabric store was a common practice for keeping moths away. Thimbles have also been used as love-tokens and to commemorate important events. A miniature thimble is one of the tokens in the game of Monopoly. People who collect thimbles are known as digitabulists.

Corning Glass Works in New York developed a prototype thimble during the Second World War due to the shortage of metal needed for defense purposes. The thimbles were made of light blue and clear Pyrex, but were never sold commercially.

On December 3, 1979, a London dealer bid the sum of $18,000 USD for a dentil shaped Meissen porcelain thimble, circa 1740, at Christie's auction in Geneva, Switzerland. The thimble, just over a half inch high, was painted in a rare lemon-yellow color about the band. It also had tiny harbor scene hand painted within gold-trimmed cartouches. The rim was scalloped with fired gold on its bottom edge. The thimble now belongs to a Meissen collector in Canada who wanted it for its lemon-yellow color.

During November 1994, Sirthey's saleroom yielded a one of a kind Meissen thimble bearing an armorial coat of arms at the massive price of GBP 26,000.

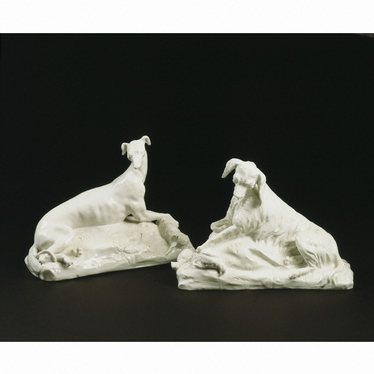

On 13 June 1995, Sotheby's sold a Meissen thimble adorned with two pugs for GBP 10,350.

Category:Tools Category:Sewing equipment Category:Embroidery equipment

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.