Jainism ( /ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/; Sanskrit: जैनधर्म - Jainadharma, Tamil: சமணம் - Samaṇam Kannada: ಜೈನ ಧರ್ಮ - Jaina Dharma), is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state of supreme being is called a jina ("conqueror" or "victor"). The ultimate status of these perfect souls is called siddha. Ancient texts also refer to Jainism as shramana dharma (self-reliant) or the "path of the niganthas" (those without attachments or aversions).

/ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/; Sanskrit: जैनधर्म - Jainadharma, Tamil: சமணம் - Samaṇam Kannada: ಜೈನ ಧರ್ಮ - Jaina Dharma), is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state of supreme being is called a jina ("conqueror" or "victor"). The ultimate status of these perfect souls is called siddha. Ancient texts also refer to Jainism as shramana dharma (self-reliant) or the "path of the niganthas" (those without attachments or aversions).

Jain doctrine teaches that Jainism has always existed and will always exist,[2][3][4] although historians date the foundation of the organized or present form of Jainism to sometime between the 9th and the 6th century BCE.[5][6] Like most ancient Indian religions, Jainism may have its roots in the Indus Valley Civilization, reflecting native spirituality prior to the Indo-Aryan migration into India.[7][8][9] Other scholars suggested the shramana traditions were separate and contemporaneous with Indo-Aryan religious practices of the historical Vedic religion.[10]

Contemporary Jainism is a small but influential religious minority with as many as 6 million followers in India,[11] and growing immigrant communities in North America, Western Europe, the Far East, Australia and elsewhere.[12] Jains have significantly influenced and contributed to ethical, political and economic spheres in India. Jains have an ancient tradition of scholarship and have the highest degree of literacy for a religious community in India.[13][14] Jain libraries are the oldest in the country.[15]

Five Mahavratas of Jain ascetics

Jainism encourages spiritual development through cultivation of one's own personal wisdom and reliance on self control through vows (Sanskrit: व्रत, vrata).[16] The triple gems of Jainism - right vision or view (Samyak Darshana), right knowledge (Samyak Gyana) and right conduct (Samyak Charitra) - provide the path for attaining liberation from the cycles of birth and death. When the soul sheds its karmic bonds completely, it attains divine consciousness. Those who have attained moksha are called siddhas, while those attached to the world through their karma are called samsarin. Every soul has to follow the path, as explained by the Jinas and revived by the tirthankaras, to attain complete liberation or nirvana. Jains do not believe in a creator deity that could be responsible for the manifestation, creation, or maintenance of this universe. The universe is self regulated by the laws of nature. Jains believe that life exists in various forms in different parts of the universe including earth. Jainism has extensive classification of various living organisms including micro-organisms that live in mud, air and water. All living organisms have soul and therefore need to be interacted with, without causing much harm.

Jains believe that to attain enlightenment and ultimately liberation from all karmic bonding, one must practice the following ethical principles not only in thought, but also in words (speech) and action. Such a practise through lifelong work towards oneself is called as observing the Mahavrata ("Great Vows"). These vows are:

- Ahimsa (Non-violence)

- To cause "no harm" to living beings (on the lines of "live" and "let live"). The vow involves "minimizing" intentional as well as unintentional harm to another living creature. There should even be no room for any thought conjuring injury to others, let alone talking about it or performing of such an act.[17] Besides, it also includes respecting the views of others (non-absolutism and acceptance of multiple views).

- Satya (Truthfulness)

- To always speak of truth such that no harm is caused to others. A person who speaks truth becomes trustworthy like a mother, venerable like a preceptor and dear to everyone like a kinsman. Given that non-violence has priority, all other principles yield to it whenever there is a conflict. For example, in a situation where speaking truth would lead to violence, it would be perfectly moral to remain silent (for you are neither being untrue, nor causing violence by way of truth)

- Asteya (Non-stealing)

- Not to take into possession, anything that is not willingly offered. It is the strict adherence to one's own possessions without desiring for the ones that belong to others. One should remain satisfied by whatever is earned through honest labour. Any attempt to squeeze material wealth from others and/or exploit the weak is considered theft. Some of the guidelines for this principle follow as under:

- Always give people fair value for their labor or product.

- Not to take into possession materials that are not earned or offered by others.

- Not to take materials into personal possession that have been dropped off or forgotten by others.

- Not to purchase materials as a result of being cheaper in value, if the resultant price reduction is a result of improper method of preparation. For instance, products made out of raw materials obtained by way of pyramid schemes, illegal businesses, stolen goods, etc., should be strictly prohibited

- Brahmacharya (Celibacy)

- To exercise control over senses (including mind) from indulgence. The basic intent of this vow is to conquer passion, thus preventing wastage of energy in the direction of pleasurable desires. During observance of this vow, the householder must not have a sensual relationship with anybody other than one's own spouse. Jain monks and nuns practice complete abstinence from any sexual activity.[18]

- Aparigraha (Non-possession, Non-materialism)

- To observe detachment from people, places and material things. Ownership of an object itself is not possessiveness; however, attachment to the owned object is possessiveness. For householders, non-possession is owning without attachment, because the notion of possession is illusory. The basic principle behind observance of this vow lies in the fact that life changes. What you own today may not be rightfully yours tomorrow. Hence the householder is encouraged to discharge his or her duties to related people and objects as a trustee, without excessive attachment or aversion. For monks and nuns, non-possession involves complete renunciation of property and human relations.[19]

Jains hold that the universe and its natural laws are eternal, and have always existed in time. However, the world constantly undergoes cyclical changes as per governing universal laws. The universe is occupied by both living beings (jīva) and non-living objects (Ajīva). The samsarin soul incarnates in various life forms during its journey over time. Human, sub-human (category catering to inclusion of animals, birds, insects and other forms of living creatures), super-human (heavenly beings) and hellish-beings are the four forms of samsarin soul incarnations. A living being's thoughts, expressions and actions, executed with intent of attachment and aversion, give rise to the accumulation of karma. These influxes of karma in turn contribute to determination of circumstances that would hold up in our future in the form of rewards or punishment. Jain scholars have explained in-depth methods and techniques that are said to result in clearance of past accumulated karmas as well as stopping the inflow of fresh karmas. This is the path to salvation in Jainism.

A major characteristic of Jain belief is the emphasis on the consequences of not only physical but also mental behaviours.[20] One's unconquered mind tainted with anger, pride (ego), deceit, and greed joined with uncontrolled sense organs are powerful enemies of humans. Anger comes in the way of good human relations, pride destroys humility, deceit destroys peace, and greed destroys good judgement. Jainism recommends conquering anger by forgiveness, pride (ego) by humility, deceit by straight-forwardness, and greed by contentment.[21]

The principle of non-violence seeks to minimize karmas that limit the capabilities of one's own soul. Jainism views every soul as worthy of respect because it has the potential to become siddha (paramatma "highest soul"). Because all living beings possess a soul, great care and awareness is essential in one's actions. Jainism emphasizes the equality of all life, advocating harmlessness towards all, whether great or small. This policy extends even to microscopic organisms.

Jainism acknowledges that every person has different capabilities and capacities to practice and therefore accepts different levels of compliance for ascetics and householders. The Great Vows are prescribed for Jain monastics while limited vows (anuvrata) are prescribed for householders. Householders are encouraged to practice five cardinal principles of non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, celibacy, and non-possessiveness with their current practical limitations, while monks and nuns have to observe them very strictly. With consistent practice, it is possible to overcome the limitations gradually, accelerating spiritual progress. [22]

- Every living being has a soul.[23]

- Every soul is potentially divine, with innate qualities of infinite knowledge, perception, power, and bliss (masked by its karmas).

- Therefore regard every living being as you do yourself, harming no one and being kind to all living beings.

- Every soul is born as a heavenly being, human, sub-human or hellish being according to its own karma.

- Every soul is the architect of its own life, here or hereafter.[24]

- When a soul is freed from karmas, it becomes free and attains divine consciousness, experiencing infinite knowledge, perception, power, and bliss (Moksha).[25]

- The triple gems of Jainism ("Right View, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct") provide the way to this realisation.[26] There is no supreme divine creator, owner, preserver, or destroyer. The universe is self-regulated, and every soul has the potential to achieve divine consciousness (siddha) through its own efforts.

- Non-violence (to be in soul consciousness rather than body consciousness) is the foundation of right view, the condition of right knowledge and the kernel of right conduct. It leads to a state of being unattached to worldly things and being non-judgmental and non-violent; this includes compassion and forgiveness in thoughts, words and actions toward all living beings and respecting views of others (non-absolutism).

- Jainism stresses the importance of controlling the senses including the mind, as they can drag one far away from true nature of the soul.

- Limit possessions and lead a life that is useful to yourself and others. Owning an object by itself is not possessiveness; however, attachment to an object is possessiveness.[27] Non-possessiveness is the balancing of needs and desires while staying detached from our possessions.

- Enjoy the company of the holy and better-qualified, be merciful to afflicted souls, and tolerate the perversely inclined.[28]

- Four things are difficult for a soul to attain: 1. human birth, 2. knowledge of the laws governing the souls, 3. absolute conviction in the philosophy of non-violence, and 4. practicing this knowledge with conviction in everyday life activities.

- It is, therefore, important not to waste human life in evil ways. Rather, strive to rise on the ladder of spiritual evolution.

- The goal of Jainism is liberation of the soul from the negative effects of unenlightened thoughts, speech, and action. This goal is achieved through clearance of karmic obstructions by following the triple gems of Jainism.

- Namokar Mantra is the fundamental prayer in Jainism and can be recited at any time of the day. Praying by reciting this mantra, the devotee bows in respect to liberated souls still in human form (arihants), fully liberated souls forever free from rebirth (siddhas), spiritual leaders (Acharyas), teachers, and all the monks and nuns.[29] By saluting them saying "namo namaha", Jains receive inspiration from them to follow their path to achieve true bliss and total freedom from the karmas binding their souls. In this main prayer, Jains do not ask for any favours or material benefits. This mantra serves as a simple gesture of deep respect toward beings that are more spiritually advanced. The mantra also reminds followers of the ultimate goal of reaching nirvana or moksha.[30]

- Jains worship the icons of jinas, arihants and Tirthankaras, who have conquered their inner passions and attained divine consciousness, and study the Scriptures of these liberated beings.

- Jainism acknowledges the existence of powerful heavenly souls that look after the well-being of Tirthankaras. Usually they are found in pairs around the icons as male (yaksha) and female (yakshini) guardian deities. Even though they have supernatural powers, these deities are also souls wandering through the cycles of births and deaths just like most other souls. Over time, people began worshiping these deities as well.[31]

Aspects of Violence (Himsa)

Jains hold the above five major vows at the center of their lives. These vows cannot be fully implemented without the acceptance of a philosophy of non-absolutism. Anēkāntavāda ("multiple points of view") is a foundation of Jain philosophy. This philosophy allows the Jains to accept the truth in other philosophies from their perspective and thus inculcating a tolerance for other viewpoints. Jain scholars have devised methods to view both physical objects and abstract ideas from different perspectives systematically. This is the application of non-violence in the sphere of thought. It is a Jain philosophical standpoint just as there is the Advaitic standpoint of Sankara and the standpoint of the "middle way" of the Buddhists.[32] This search to view things from different angles leads to understanding and toleration of different and even conflicting views. When this happens prejudices subside and a tendency to accommodate increases. The doctrine of Anēkānta is therefore a unique experiment of non-violence at the root.[23]

A derivation of this principle is the doctrine of Syādvāda that highlights every model relative to its view point. It is a matter of our daily experience that the same object that gives pleasure to us under certain circumstances becomes boring under different situations. Nonetheless, relative truth is useful, as it is a stepping-stone to the ultimate realization and understanding of reality. The doctrine of Syādvāda is based on the premise that every proposition is only relatively true. It all depends on the particular aspect from which we approach that proposition. Jains, therefore, developed logic that encompasses seven-fold predication so as to assist in the construction of proper judgment about any proposition.

Syādvāda provides Jains with a systematic methodology to explore the real nature of reality and consider the problem in a non-violent way from different perspectives. This process ensures that each statement is expressed from seven different conditional and relative viewpoints or propositions, and thus it is known as theory of conditioned predication. These seven propositions are described as follows:

- 1.Syād-asti — "in some ways it is"

- 2.Syād-nāsti — "in some ways it is not"

- 3.Syād-asti-nāsti — "in some ways it is and it is not"

- 4.Syād-asti-avaktavya — "in some ways it is and it is indescribable"

- 5.Syād-nāsti-avaktavya — "in some ways it is not and it is indescribable"

- 6.Syād-asti-nāsti-avaktavya — "in some ways it is, it is not and it is indescribable"

- 7.Syād-avaktavya — "in some ways it is indescribable"

For example, a tree could be stationary with respect to an observer on earth, however it will be viewed as moving along with planet Earth for an observer in space.

Jains are very welcoming and friendly toward other faiths and often help with interfaith functions. Several non-Jain temples in India are administered by Jains. A palpable presence in Indian culture, Jains have contributed to Indian philosophy, art, architecture, and science.

Karma in Jainism conveys a totally different meaning than commonly understood in the Hindu philosophy and western civilization.[33] It is not the so called inaccessible force that controls the fate of living beings in inexplicable ways. It does not simply mean "deed", "work", nor mystical force (adrsta), but a complex of very fine matter, imperceptible to the senses, which interacts with the soul in intensity and quantity proportional to the thoughts, speech and physical actions carried out with attachments and aversions, causing further bondages. Karma in Jainism is something material (karmapaudgalam), which produces certain conditions, like a medical pill has many effects.[34] The effects of karma in Jainism is therefore a system of natural laws rather than moral laws. When one holds an apple in one's hand and then lets go of the apple, the apple will fall due to gravitational force. In this example, there is no moral judgment involved, since this is a mechanical consequence of a physical action.[35] The concept of Karma in Jainism is basically a reaction due to the attachment or aversion with which an activity (both positive and negative) is executed in thought, verbal and physical sense. Extending on the example outlined, the same apple dropped within a zero gravity environment such as a spacecraft circling around earth, will float in its place. Similarly, when one acts without attachment and aversion there will be no further karmic bonding to the soul.

Karmas are grouped as Destructive Karmas, that obstruct the true nature of the soul and Non-Destructive Karmas that only affect the body in which the soul resides. As long as there are Destructive Karmas, the soul is caged in a body and will have to experience pain and suffering in many different forms. Jainism has extensive sub-classifications and detailed explanations of each of these major categories. Jain liturgy and scriptures explains ways to stop the influx as well as get rid of the accumulated karmas.

Jainism prescribes mainly two methods for shedding karmas (Nirjara), accumulated by the soul.

- Passive Method – By allowing past karmas to ripen in due course of time and experiencing the results, both good and bad with equanimity. If the fruits of the past karmas are received with attachment or with agitation then the soul earns fresh karmic bondages. It is also not possible for the soul to know before-hand when and which karma will start to produce results. Therefore, a person should practice equanimity under all circumstances.

- Active Method – By practicing internal and external austerities (penances or tapas) so as to accelerate the ripening process as well as reducing the effects produced. This is the recommended approach as it prepares and conditions the soul and reminds one to be vigilant.

The internal austerities are

- Atonement of sinful acts

- Practice politeness and humility - in spite of having comparatively more wealth, wisdom, social status, power, etc.

- Service to others, especially monks, nuns, elders and the weaker souls without any expectations in return

- Scriptural study, questioning and expanding the spiritual knowledge

- Abandonment of passions – especially anger, ego, deceit and greed

- Meditation

The external austerities are meant to discipline the sensual cravings. They are

- Fasting

- Eating less than one's normal diet

- Abstention from tasty and stimulating food

- Practising humility and thankfulness – by seeking help and offering assistance without egoistic tendencies

- Practising solitude and introspection

- Mastering demands of the body

Main article:

Tirthankara

Sculpture representing two founders of Jainism: left,

Rishabha first of the 24

tirthankaras; right

Mahavira, the last of those 24, who consolidated and reformed the religious and philosophical system.

The purpose of life is to undo the negative effects of karma through mental and physical purification. This process leads to liberation accompanied by a great natural inner peace. A soul is called a 'victor' (in Sanskrit/Pali language, Jina) because one has achieved liberation by one's own efforts. A Jain is a follower of Jinas ("conquerors").[36][37] Jinas are spiritually advanced human beings who rediscovered the dharma, became fully liberated from the bondages of karma by conquering attachments and aversions, and taught the spiritual path to benefit all living beings.

Jains believe that dharma and true living declines and revives cyclically through time. The special Jinas who not only rediscover dharma but also preach it for the Jain community are called Tirthankara. The literal meaning of Tirthankara is "ford-builder". Jains compare the process of becoming a pure soul to crossing a swift river, an endeavour requiring patience and care. A ford-builder has already crossed the river and can therefore guide others. Only a few souls that reach Arihant status become Thirthankars who take a leadership role in assisting the other souls to move up on the spiritual path.

Jaina tradition identifies Rishabha (also known as Adinath) as the first tirthankar of this declining (avasarpini) time cycle (kalachakra).[38] The 24th, and last Tirthankar is Mahavira, who lived from 599 to 527 BCE. The 23rd Tirthankar, Parsva, lived from 877 to 777 BCE.[23][39] The last two Tirthankaras, Parshva and Mahavira, are historical figures whose existence is recorded.[39] The 24 Tirthankaras in chronological order are: Rishabha, Ajitnath, Sambhavanath, Abhinandannath, Sumatinath, Padmaprabha, Suparshvanath, Chandraprabha, Pushpadanta (Suvidhinath), Sheetalnath, Shreyansanath, Vasupujya, Vimalnath, Anantnath, Dharmanath, Shantinath, Kunthunath, Aranath, Mallinath, Munisuvrata, Naminatha, Neminath, Parshva and Mahavira (Vardhamana).

These special Jinas are also referred to in different languages as Bhagvān and Iṟaivaṉ (Kannada: ತೀರ್ಥಂಕರ Tīrthaṅkara, Tamil: இறைவன் Iṟaivaṉ and Hindi: भगवान Bhagvān). Tirthankaras are not regarded as deities in the pantheistic or polytheistic sense, but rather as pure souls that have awakened the divine spiritual qualities that lie dormant within each of us. Apart from the Tirthankaras, Jains worship special Arihants such as Bahubali. According to the scriptures, Bahubali, also known as Gommateshvara, was the second of the one hundred sons of Rishabha and king of Podanpur. A statue of Bahubali is located at Shravana Belagola in the Hassan district of Karnataka State. It is a sacred place of pilgrimage for Jains. When standing at the statue's feet looking up, one sees the saint against the vastness of the sky. This statue of Bahubali is carved from a single large stone that is fifty-seven feet high. The giant image was carved in 981 AD., by order of Chavundaraya, the minister of the Ganga King Rachamalla, and is considered the largest stone sculpture in the world.

Main article:

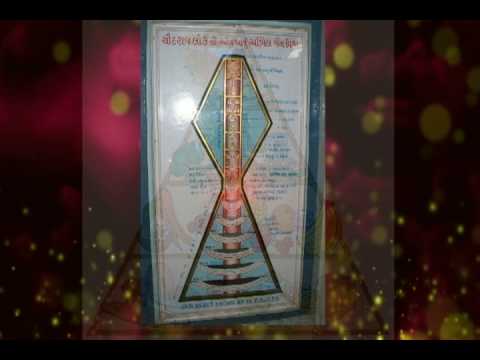

Jain cosmology

Structure of Universe as per the Jain Scriptures.

Depiction of Siddha Shila as per

Jain cosmology, which is abode of infinite Siddhas.

According to Jain beliefs, the universe was never created, nor will it ever cease to exist. Therefore, it is shaswat (eternal) from that point of view. It has no beginning or end, but time is cyclical with progressive and regressive spirituality phases. In other words, within the universe itself there will be constant changes, movements and modifications in line with the macro phases of the time cycles.

Jain text claims that the universe consists of infinite amount of Jiva (life force or souls), and infinite amount of Ajiva (lifeless objects). The shape of the Universe as described in Jainism is shown alongside. At the very top end of the universe is the residence of the liberated souls that reached the siddha status. This supreme abode is above a crescent like boundary. Below this arch is the Deva Loka (Heaven), where all devas, powerful souls enjoying the positive karmic effects, reside. According to Jainism, there are sixteen heavens in total.[40] The enjoyment in heaven is time limited and eventually the soul has to be reborn after its positive karmic effect is exhausted. Similarly, beneath the "waist" like area are the Narka Loka (Hells). There are seven hells, each for a varying degree of suffering a soul has to go through as consequences of its negative karmic effects. From the first to the seventh hell, the degree of suffering increases and light reaching it decreases (with no light in the seventh hell). The ray of hope is that the suffering in hell is also time limited and the soul will be reborn somewhere else in the universe after its negative karmic effects are exhausted. Human, animal, insect, plant and microscopic life forms reside on the middle part of the universe. Ultimate liberation is possible only from this region of the universe.

In Jainism, time is divided into Utsarpinis (Progressive Time Cycle) and Avasarpinis (Regressive Time Cycle). An Utsarpini and an Avasarpini constitute one Time Cycle (Kalachakra). Every Utsarpini and Avasarpini is divided into six unequal periods known as Aras. During the Utsarpini half cycle, humanity develops from its worst to its best: ethics, progress, happiness, strength, health, and religion each start the cycle at their worst, before eventually completing the cycle at their best and starting the process again. During the Avasarpini half-cycle, these human experiences deteriorate from the best to the worst. Jains believe we are currently in the fifth Ara of the Avasarpini phase.

During the first and last two Aras, the knowledge and practice of dharma lapse among humanity and then reappear through the teachings of enlightened humans, those who have reached liberation from their karma, during the third and fourth Aras. Traditionally, in our universe and in this time cycle, Rishabha is regarded as the first to realize the truth. Mahavira (Vardhamana) was the last (24th) Tirthankara to attain enlightenment. For further reading on this aspect of Jainism refer to 'The Jaina Path of Purification' by P.S. Jaini.[41]

Jains are vegetarians. They avoid eating root vegetables in general, as cutting root from a plant kills it unlike other parts of the plant (leaf, fruit, seed, etc.). Furthermore, according to Jain texts, root vegetables contain infinite microorganisms called nigodas. Followers of Jain dharma eat before the night falls. They filter water regularly so as to remove any small insects that may be present and boil water prior to consumption.

Jain monks and nuns practice strict asceticism and strive to make their current birth their last, thus ending their cycle of transmigration.[42] The lay men and women also pursue the same five major vows to the limited extent depending on their capability and circumstances. Following the primary non-violence vow, the laity usually choose professions that revere and protect life and totally avoid violent livelihoods.

Jain monks and nuns walk barefoot and sweep the ground in front of them to avoid killing insects or other tiny beings. Even though all life is considered sacred by the Jains, human life is deemed the highest form of life. For this reason, it is considered vital never to harm or upset any person. Along with the Five Vows, Jains avoid harboring ill will and practice forgiveness. They believe that atma (soul) can lead one to becoming parmatma (liberated soul) and this must come from one's inner self. Jains refrain from all violence (ahimsa) and recommend that sinful activities be avoided.

Pratikraman (turning back from transgression) is a practice of confession and repentance. This is a process of looking back at the bad thoughts and actions carried out during daily activities and learn from this process so as to resolve not to commit those mistakes again. Forgiving others for their faults, extending friendship and asking forgiveness for their own wrongful acts without reservation is part of this process. This enables Jains to get away from the tendency of finding fault in others, criticizing others and to develop habit of self-analysis, self-improvement and introspection.

Jains practice Samayika, which is a Sanskrit word meaning equanimity. During this practice, they remain calm and undisturbed. This helps in recollecting the teachings of Thirthankars and discarding sinful activities for a minimum of 48 minutes.

Mahatma Gandhi was deeply influenced (particularly through the guidance of Shrimad Rajchandra) by Jain tenets such as peaceful, protective living and honesty, and made them an integral part of his own philosophy.[43]

Jainism has several different traditions. Historically, this has led to traditions refusing to recognize each other's religious texts as authoritative. For example, the Digamabaras reject the Svetambara canon.[44] Even though there are some differences in customs and practices among them, the core belief systems are the same. Each tradition brings a unique perspective and completes the picture in the true sense of Non-Absolutism (Anekantvad). For this reason Jains are encouraged to keep their tradition, and at the same time respect other practices so as to complete the Jain view. All traditions unanimously accept and believe in the core Jain philosophies including the major vows of Non-violence, Truthfulness, Non-stealing, Celibacy and Non-possession.

Jainism is mainly divided into two major sects, namely Svetambara and Digambara. Jainism has a distinct idea underlying Tirthankara worship. The physical form is not worshipped, but the characteristics of the Tirthankara (virtues, qualities) are praised and emulated. Tirthankaras remain role-models, and sects such as the Sthanakavasi and Terapanth stringently reject idol worship. However, Murtipujak and Digambara sects allow praying before idols so as to assist in stimulating and focusing thoughts while praying.

Compassion for all life, human and non-human, is central to Jainism. Human life is valued as a unique, rare opportunity to reach enlightenment; to kill any person, no matter what crime he may have committed, is considered unimaginably abhorrent. It is a religion that requires monks and laity, from all its sects and traditions, to be vegetarian. Some Indian regions, such as Rajasthan, Gujarat and Karnataka, have been strongly influenced by Jains and often the majority of the local Hindus of every denomination have also become vegetarian.[45]

Jain scriptures offer extensive guidance on meditation techniques to achieve full knowledge and awareness. It offers tremendous physical and mental benefits. Jain meditation techniques are designed to assist the practitioner to remain apart from clinging and hatred thereby liberating from karmic bondages through the Ratnatraya: right perception, right knowledge and right conduct.[46] Meditation in Jainism aims at taking the soul to status of complete freedom from bondages.[47]

Meditation assists greatly in managing and balancing one's passion. Great emphasis is placed on the control of internal thoughts, as they influence the behavior, actions and goals. It prescribes twelve mindful reflections or contemplations to help in this process. They are called Bhavanas or Anuprekshas that assist one to remain on the right course of life, and not stray away. Please note that Jains apply the sevenfold predicate methodology of Syadvada, which includes the consideration of different views on each of these topics including the opposite view. The twelve contemplations for meditation are:

- Impermanence - Everything in this world is subject to change and transformation. Spiritual values are therefore worth striving for as they alone offer the soul, its ultimate freedom and stability.

- Protection - Under this reflection, one thinks about how helpless one is against old age, disease and death. The soul is its own saviour and to achieve total freedom one needs to follow the non-violent path of Arihants, Siddhas and practicing saints. Leaders with their powerful armies, scientists with their latest advances in technology cannot provide the protection from the eventual decay and death. The refuge to things other than the non-violent path are due to delusion, is unfortunate, and must be avoided.

- Worldly Existence - The soul transmigrates from one life form to another and is full of pain and miseries. There are no permanent relationships as the soul moves from one body form to another and can only exit this illusion through liberation from the cycles of birth, growth, decay and death.

- Solitude of the Soul - The soul has to bear the consequences of the positive and negative karmas alone. Such thoughts will stimulate to get rid of the existing karmas by one's own efforts and lead a peaceful life of co-existence.

- Separateness of Soul - Under this reflection, one thinks that the soul is separate from other objects or living beings. One should think even the current body is not owned by the soul. It is however an important vehicle to lead a useful life to progress the soul further. The soul therefore should not develop attachment or aversion to any worldly objects.

- Impureness of the body - Under this section of thought, one is urged to think about constituent elements of one's body so as to compare and contrast it with the purity of soul. This kind of concentration assists in detaching emotionally from one's body.

- Influx of Karma - Every time the soul enjoys or suffers through the five senses (touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing) with attachment, aversion or ignorance, it attracts new karma. Practising this reflection, reminds the soul to be more careful.

- Stoppage of influx of Karma - In this reflection, one thinks about stopping evil thoughts and cultivates development of right knowledge that assists to control the wandering mind.

- Karma shedding - Under this reflection, one thinks about practising external and internal austerities to shed the previously accumulated karma. This assists in development of right discipline as a matter of routine habit.

- Universe - Universe consists of Souls, Matter, Medium of motion, Medium of Rest, Space and Time. To think of the nature and structure of universe helps one understand the complex dynamics of eternal modifications and work towards the goal of freeing the soul from the seemingly never ending changes.

- Difficulties in developing triple gems of Jainism - It is very difficult for the transmigrating soul in this world to develop the Right View, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct. Just like one cannot aspire to become a doctor or lawyer or engineer without going through the development process starting from the very basic skill set developments in primary and secondary schooling, spiritual development also needs to go through several stages or steps. Depending on one's current spiritual progress and situation, the challenges faced will differ. Working through the difficulties and applying practical solutions will assist one to continuously make improvements, thereby moving the soul to its goal of ultimate liberation.

- Difficulties in practising Jain Dharma - Jain Dharma is characterised by the following;

-

- Forbearance and Forgiveness

- Humility

- Straightforwardness

- Purity

- Truth

- Self-restraint, control of senses and mind

- External Penance

- Renunciation

- Neither attachment nor aversion

- Celibacy

- In this reflection, the practitioner thinks about the difficulties to practice all of these in the practical world and work through the challenges depending on one's current capabilities and circumstances.

Jains are encouraged to reflect on these thoughts with the following four virtues or value systems clearly in force. They are:

- Peace, love and friendship to all.

- Appreciation, respect and delight for the achievements of others.

- Compassion to souls who are suffering.

- Equanimity and tolerance in dealing with other's thoughts, words and actions.

Mulnayak Shri Adinath Bhagwan, Bibrod Jain Temple, Ratlam, Madhya Pradesh, India

In India there are several Jain Monks, in categories like Acharya, Upadhyaya and Muni. Trainee ascetics are known as Ailaka and Ksullaka in the Digambara tradition. There are two categories of ascetics, Sadhu (monk) and Sadhvi (nun). They practice the five Mahavratas, three Guptis and five Samitis:

Five major vows (Mahavrata)

- Non-violence (Ahinsa): Non-violence in thought, word and deed so as not to cause harm to any living beings

- Truthfulness (Satya): Truth, which is (hita) beneficial, (mita) succinct, and (priya) pleasing. In other words, to speak the harmless truth

- Non-stealing (Astey): Not to take anything that has not been given to them willingly by the owner

- Chastity (Brahmacharya): Absolute purity of mind and body without indulging in sensual pleasure

- Non-possession (Aparigraha): Exercise no attachment or aversion to all people, places, and material objects around.

Three Restraints (Gupti)

- Control of the mind (Mangupti)

- Control of speech (Vachangupti)

- Control of body (Kayagupti)

Five Carefulness (Samiti)

- Carefulness while walking (Irya Samiti)

- Carefulness while communicating (Bhasha Samiti)

- Carefulness while eating (Eshana Samiti)

- Carefulness while handling their fly-whisks, water gourds, etc. (Adan Nikshepan Samiti)

- Carefulness while disposing of bodily waste matter (Pratishthapan Samiti)

Digambara monks do not wear any clothes and are nude. They practice non-attachment to the body and hence, wear no clothes. Svetambara monks and nuns wear white clothes. Svetambaras believe that monks and nuns may wear simple, unstitched white clothes as long as they are not attached to them. Jain monks and nuns travel on foot. They do not use mechanical transport.

Digambaras take up to eleven oaths. Digambara monks eat standing in one place in their palms without using any utensil. They eat only once a day.

Jains practice strict vegetarianism. The practice of vegetarianism is instrumental for the practice of non-violence and peaceful co-operative co-existence. Basic non-violence principles can be performed depending on one's capability and specific situation in terms of meeting one's life's demands and expectations. Jainism acknowledges that it is impossible to discharge one's duties without some degree of himsa/violence, but encourages to minimise as much as possible. Jains are strictly forbidden to use any leather or silk products since they are derived by killing of animals. Jains are prohibited from consuming root vegetables such as potatoes, garlic, onions, carrots, radishes, cassava, sweet potatoes, turnips, etc., as the plant needed to be killed in the process of accessing these prior to their end of life cycle. In addition, the root vegetables interact with soil and therefore contain far more micro-organisms than other vegetables. Also, the root vegetables themselves are composed of infinite smaller organisms, hence, consuming these vegetables would mean killing all those organisms as well. However, they consume rhizomes such as dried turmeric and dried ginger. Eggplants, pumpkins, etc. are also not consumed by some Jains owing to the large number of seeds in the vegetable, as a seed is a form of life. However, tomatoes are consumed normally as its seeds are difficult to be killed (even at high temperatures/pressures). Mushrooms, fungus and yeasts are forbidden because they are parasites, grow in non-hygienic environments and may harbor other life forms. Jains are also not supposed to consume food left overnight because of contamination by microbes. Most Jain recipes substitute potato with plantain.[48]

Apart from all these, Jains also follow strict diets on "teethees" - eleven days (six days in Shukla Paksha - New Moon Fortnight and five days in Krishna Paksha - Full Moon Fortnight). They do not eat greens on these days, also termed as not to touch / use any sharp cutting object in the kitchen. These days and are enlisted below: 1. All Bij - Second day of both the fortnights for aaradhna of "Samyag Darshan" 2. Pacham - Fifth day of Shukla Paksha & Agyiras - Eleventh day of both the fortnights for aaradhna of 14 Purva Gyan 3. Aatham - Eight day of both the fortnights, Chaudas - Fourteenth day of both the fortnights, Punam - Full Moon Day & Amavas - New Moon Day for aaradhna of Charitra. The reason for stricter dietary observance on these eleven days is that the probability of the finalisation of the next birth is much more on these days compared to the other days.

Fasting is one of the main tools for practicing external austerity. It helps to keep the demands of the body under check and assists in the focus on the upliftment of the soul. Spiritually, it helps in melting away the bad karmas accumulated by an individual. Depending on the capacity of an individual, there are several types of fasting:

- Complete fasting: giving up food and/or water completely for a period

- Partial fasting: eating less than you need to avoid hunger

- Vruti Sankshepa: limiting the number of items of food eaten

- Rasa Parityaga: giving up favourite foods

During fasting one immerses oneself in religious activities such as worshipping, serving the saints (monks and nuns & to be in their proximity), reading scriptures, meditating, and donating to the right recipients. However, before starting the fast Jains take a small vow known as pachhchhakhan. A person taking the vow is bound to it and breaking it is considered to be a bad practice. Also, one gets the fruits of a fast only if he is bound by pachhchhakhan.

Most Jains fast at special times, such as during festivals (known as Parva. Paryushana and Ashthanhika are the main Parvas, which occurs 3 times in a year) and on holy days (eighth & fourteenth days of the moon cycle). Paryushana is the most prominent festival (lasting eight days for Svetambara Jains and ten days for Digambaras) during the monsoon. Most people fast during Paryushana because even the trouble-causing planets Rahu and Ketu become calm and instead help the penancing devotees. However, a Jain may fast at any time of the year. Fasting is also one of the ways of absolving one's Spashta, Baddha, or Nidhatta karmas. Variations in fasts encourage Jains to do whatever they can to maintain self-control over their abdominal desires.

A unique ritual in this religion involves a holy fasting until death called sallekhana. Through this one achieves a death with dignity and dispassion as well as a reduction of negative karma to a great extent.[49] When a person is aware of approaching death, and feels that s/he has completed all duties, s/he willingly ceases to eat or drink gradually. This form of dying is also called Santhara. It can be as long as 12 years with gradual reduction in food intake. Considered extremely spiritual and creditable, with all awareness of the transitory nature of human experience, it has recently led to a controversy. In Rajasthan, a lawyer petitioned the High Court of Rajasthan to declare santhara illegal. Jains see santhara as spiritual detachment, a declaration that a person has finished with this world and now chooses to leave. This choice however requires a great deal of spiritual accomplishment and maturity as a pre-requisite.

A person undergoing a complete fast can eat nothing and drink only boiled water during his fasting period. The water has to be boiled for at least twenty minutes to ensure that all the living organisms in it die, and new ones don't form, thereby reducing the amount of himsa that a fasting person does. The unboiled water called sachet (meaning, full of life) is turned achet (meaning devoid of life) on boiling for this long. The boiled water remains achet for only five hours. So after five hours, it should be boiled again for at least another twenty minutes to ensure that it remains achet - fit for use to a fasting person.

All the different types of complete fasts mandate an individual to do the following steps stringently:

- Initiation of the fast: The person desiring to observe a fast on a particular day has to take the vow of Chauvihar (meaning not eat or drink anything till at least 48 minutes after sunrise the next day) at least 48 minutes before sunset the previous day.

- Ingestion during the fast: On the day of fast, he has to take the pachhchhakhan of fast. He cannot eat anything on the day of fast. However, he may drink boiled water after at least 48 minutes after sunrise till at most 48 minutes before sunset on that day. At least 48 minutes before the sunset, he should take the vow of Chauvihar.

- Termination of the fast: He can break his fast only on the day after the day of fast after at least 48 minutes after sunrise, after taking the vow of Naukaarsi, Porsi, Saadh Porsi, Parimuddhi, etc. Optionally, he may continue his fast for that day also by taking the necessary vows and following them.

Chauvihar Upvas, Chauvihar Chhath, Chauvihaar Attham, Chauvihaar Atthai, etc. are those types of complete fasts in which the person can't drink even boiled water during his fasting period. He can eat nothing and drink nothing. The process of initiation and termination of the fast is the same as mentioned above.

- Maasakshaman: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat anything for thirty days.

- Atthai: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat anything for eight days. Normally on 8th day of fasting, the success is celebrated by the community by organising a procession to the temple. On the 9th day, the person will stop fasting. The relatives and friends will come and help the person to break the fast.

- Tela/Athham: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat anything for three days.

- Chhathh: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat anything for two days.

- Upvas: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat anything for one whole day.

- Chauvihar Upvas: A person practising this form of fasting will not eat or drink anything for one whole day.

- Varshitap: This is a difficult form of fasting and demands a high level of skill and discipline; it is based on the story of Lord Rishabh not eating or drinking for 400 days. It is possible for people to try a variation of Varshitap by eating every alternate day, in general. They can eat only twice in every alternate day, but in between during some special calendar events, they may have to fast longer periods.

- Ayambil: A person eats only one kind of food per day, In Ayambil green vegetables, milk and milk products (including ghee),oil and/or salt (optional) are not to be used at all. Generally this kind of fast is done during a 9 day religious days called Ayambil Olee which come twice in a year i.e. in March/April and October/November.

- Ekashana: A person eats only once a day and generally they have lunch. For eating his meal, the person has to sit on the floor with his legs folded and the plate on an elevated position (maybe on another inverted plate, or on a patla). Once he starts his meal, he can't get up or even move till he finishes eating. Also, during the entire meal, his plate must not be moved at all, although the spoons and utensils on the plate can be moved. As in every type of fast they can only have food as well as water only till sunset which varies from day to day but in a yearly bases it's the same.

- Beyashana: A person eats only twice a day and generally they have lunch & dinner. All the rules of Ekashana apply to Beashana as well.

- Uunodri Tap: In this type of fast a person is allowed to have food 3 times a day but as soon as the food is served he/she has to remove one item which is his/her favorite, and also eat a morsel less than required to fill his/her stomach.

- Updhyan Tap: A person has to reside out of home for certain days (usually 51 days) and perform various rituals. He has to do upwas (single day fasting) followed by one ayambil, thereafter upwas and two ayambil and so on. It is the biggest tap as defined by Jain Monks.

- Navkarsi : One must take food or water forty-eight minutes after sunrise. Even the brushing of one’s teeth and rinsing of once mouth must be done after sunrise after the vow of Navkarsi.

- Porsi : Taking food or water three hours after sunrise.

- Sadh-porsi : Taking food or water four hours and thirty minutes after sunrise.

- Purimuddh: :Taking food or water six hours after sunrise.

- Navapad oli : During every year for 9 days starting from the 6/7th day of the bright fortnight until the full moon day in Ashwin and Chaitra months, one does Ayambil. This is repeated for the next four and half years. These ayambils can also be restricted to only one kind of food grain per day.

Jains praying at the feet of a statue of Lord Bahubali.

Om Hrim Siddhi Chakra used by Jains in dravya puja

Every day most Jains bow and say their universal prayer, the Navakar Mantra which is also known variously as Panch Parmesthi Sutra, Panch Namaskar Sutra. Navakar Mantra is the fundamental prayer in Jainism and can be recited at any time of the day. Praying by reciting this mantra, the devotee bows in respect to liberated souls still in human form (Arihantas), fully liberated souls forever free from re-birth (Siddhas), spiritual leaders (Acharyas), teachers (Upadyayas) and all the monks (sarva sadhus) and nuns (sadhvis). By saluting them saying "namo namaha", Jains receive inspiration from them to follow their path to achieve true bliss and total freedom from the karmas binding their souls. In this main prayer, Jains do not ask for any favours or material benefits. This mantra serves as a simple gesture of deep respect toward beings that are more spiritually advanced. The mantra also reminds followers of the ultimate goal of reaching nirvana or moksha. Jains worship the icons of Jinas, Arihants, and Tirthankars, who have conquered their inner passions and attained divine consciousness, and study the scriptures of these liberated beings.

Jainism acknowledges the existence of powerful heavenly souls (Yaksha and Yakshini) that look after the well-beings of Tirthankarars. Usually, they are found in pair around the icons of Jinas as male (yaksha) and female (yakshini) guardian deities. Even though they have supernatural powers, these deities are also souls wandering through the cycles of births and deaths just like most other souls. Over time, people started worshiping these deities as well.

The purpose of Jain worship or prayer is to break the barriers of the worldly attachments and desires, so as to assist in the liberation of the soul. Jain prayers and ritual in general include:

There are basically two types of prayers:

- Dravya Puja (with symbolic offerings of material objects)

- Bhav Puja (with deep feeling and meditation)

The material offerings made during the prayer are merely symbolic and are for the benefit of the offeror. The action and ritual of offering keeps the mind in meditative state. The symbolism of prayer is so strong it assists the devotee to concentrate on the virtues of Arihantas and Thirthankaras. Above all, prayer is not performed with a desire for any material goal. Jains are clear that the Jinas reside in moksha (Siddha-loka, the permanent abode of the siddhas) and are completely detached from the world. Jains have built temples where idols of tirthankaras are revered. Rituals include offering of symbolic objects and praising Tirthankaras in song. There are some traditions within Jainism that have no prayer at all, and are focused on meditation through scripture reading and philosophical discussions.

- Body cleansing: A bath should be taken before the prayer. A clean body prepares and assists the mind to be in spiritual mode. This is also symbolic of washing one's dirt or karmas. In order to assist in the meditative process place saffron paste or sandal paste on ring finger and anoint the forehead. This may be applied to earlobes, neck and other acupressure parts of the body.

- Clothes: Simple, clean washed clothes are worn. White clothing is preferred. Traditionally, men wear non-stitched cloths (dhotis and khes).

These eight pujas are enlisted chronologically below

Water Symbolizes the life's ocean of birth, struggle and death. Every living being continuously travels through the cycles of birth, life, death and misery. This prayer reminds the devotee to live with honesty, truth, love and compassion toward all living beings.

- Chandan Puja (Sandal-wood)

Sandal wood paste symbolizes Right Knowledge. The devotee reflects on Right Knowledge with clear, proper understanding of reality from different perspectives.

Flowers symbolize Right Conduct. The devotee remembers that conduct should be like a flower that provides fragrance and beauty to all living beings without discrimination.

The flame of the oil lamp represents pure consciousness or a soul without any karmic bondage. The devotee is reminded to follow the five major vows so as to attain liberation.

The incense stick symbolizes renunciation. While burning itself, it provides fragrance to others. This reminds the devotee to live life for the benefit of others, which ultimately leads to liberation.

One cannot grow rice plants by seeding with household rice. Symbolically it means that rice is the last birth. With this prayer, the devotee strives to make all effort in this life to get liberation.

- Naivedya Puja (Homemade sweets, sugar, etc.)

With this prayer, the devotee strives to reduce or eliminate attachment.

- Fal Puja (Fruit - Coconut preferred)

Fruit symbolizes moksha or liberation. The devotee is reminded to perform duties without any expectation and have love and compassion for all living beings so as to attain the ultimate fruit - Moksha.

Invocation begins with Namokar Mantra and Chattari Mangalam. In this prayer the devotee bows to Siddhas, scriptures and monks who are on the path of Right View, Knowledge and Conduct. This prayer is done by taking three full cloves and holding one clove at a time between two ring fingers while keeping the clove head pointed forward while offering and reciting. First Clove: The devotees think of the Arihants/Siddhas/Thirthankaras, Scriptures and Teachers, so that they come into their thoughts.

Second Clove: The devotees take the next step of retaining the above three in their thoughts.

Third Clove: The devotees take the last step of physically requesting them to be near them so as to guide them through on the right path.

The offerings here are similar to the Ashta Prakari Puja with flowers replaced with yellow rice, tasty food with white coconut and fruit with almond in its shell.

Barah Bhavana (12 reflections of mind) is sung as a song. After that prayer of peace for all living beings recited followed by Namokar Mantra.

At the conclusion, Visarjan (closing) prayer is recited, which means knowingly or unknowingly if any mistakes are committed during the prayer please forgive.

Jain festivals are characterized by both internal and external celebrations. The internal celebration is through praying (expressing devotion to Jinas), practicing meditation, spiritual studies and renunciation.

- Paryushana is the most important festival among the Jain festivals.It is also known as Dashlakshan parva.It happens during late August/September commencing on the twelfth day of the fortnight of the waning moon cycle and ending in the fourteenth of the fortnight of the waxing moon cycle. This is generally a rainy season in Northern parts of India. During this 18 day period[50] Jain scholars and monks visit temples and explain the Jain philosophy. Jains during this period practice external austerities such as fasting, limiting their normal activities so as to reduce the harm to worms and insects that thrive during this season. At the conclusion of the festivities, a reflection on the past is encouraged, and Pratikraman is done for repentance of faults. Forgiveness is given to and asked for from all those considered.

- Mahavir Jayanti,[51] The birthday of Mahavir, the last Thirthankar is celebrated on the thirteenth day of the fortnight of the waxing moon, in the month of Chaitra. This day occurs in late March or early April on the Gregorian calendar. Lectures are held to preach the path of virtue. People meditate and offer prayers.

- Diwali is celebrated on the new moon day of Kartik, usually in late October or early November on the Gregorian calendar. On the night of that day, Mahavira, the last Tirthankara, attained Nirvana or deliverance and attained liberation from the bondage of all karmas. During the night of Diwali, holy hymns are recited and meditation is done on Mahavira. On the very second day of Diwali they celebrate their New Year.

- Ashadh Chaturdashi, The sacred commencement of Chaturmas takes place on the 14th day of the fortnight of the waxing moon of Ashad. The Jain monks and nuns remain where they happen to be for four months until the 14th day of Kartik Shukla. During these four months the monks give daily discourses, undertake religious ceremonies, etc.

- Shrutha panchami or Gyan Panchami is on the fifth day of the fortnight of the waxing moon of Kartik (the fifth day after Diwali). This day is devoted for pure knowledge. On this day books preserved in the religious libraries are cleaned and studied.

Jainism timeline Jainism timeline

|

History

| The age of Tīrthaṇkaras |

|

2000–1500 BCE

|

Terracotta seals excavated at site suggest links of Jainism with Indus Valley civilization. Mention of Jain Tīrthaṇkaras in Vedas indicates pre-historic origins of Jainism. |

|

877–777 BCE

|

The period of Pārśva, the 23rd Tīrthaṇkaras |

|

599–527 BCE

|

The age of Māhavīra, the 24th Tīrthaṇkaras of Jainism |

|

527 BCE

|

Nirvāṇa of Māhavīra, Kevala Jñāna of his chief disciple Ganadhara Gautama and origin of Divāli. |

| The age of Kevalins |

|

523 BCE

|

As per Jain cosmology, the end of the 4th āra Duḥṣama-suṣamā and start of 5th āra Duḥṣama (sorrow and misery). The age of sorrow is said to have started three years and eight and a half months after the nirvana of Māhavīra. |

|

527–463 BCE

|

The Reign of the Kevalins — Gautama, Sudharma and Jambusvami |

| The age of Shruta-kevalins |

|

463–367 BCE

|

|

|

320–298 BCE

|

The reign of Chandragupta Maurya. became a Jain ascetic at the end of his reign. |

|

2nd century BCE

|

Kharavela, reign of King of Kalinga (Orissa). Reinstallation of Jina image taken by Nanda Kings of Magadha as per Hathigumpha inscription |

| The Agamic Age |

|

156 CE

|

Recitation of Ṣaṭkhaṇdāgama and Kaṣāyapahuda by Ācārya Dharasena to ĀcāryaPuṣpadanta and Ācārya Bhūtabali in Candragumpha in Mount Girnar. (683 years after Māhavīra) |

|

2nd Century CE

|

Kundakunda, founder of Mūla sangha– the main Digambara ascetic lineage. |

|

2nd – 3rd Century CE

|

Compilation of Tattvārthasūtra by Umāsvāti (Umāsvāmi). This was the first major Jain work in Sanskrit. |

|

300 CE

|

Two simultaneous councils for compilation of Āgamas, 827 years after Māhavīra – Mathura Council headed by Ācārya Skandila and The First Valabhi Council headed by Ācārya Nāgārjuna. |

|

453 or 466 CE

|

Second Valabhi Council headed by Devarddhi Ganin, that is, 980 or 993 AV – Final redaction and compilation of Śvetāmbara Canons. |

| The Age of Logic |

4th – 16th Century CE, also known as the age of logic, was the period of development of Jain logic, Philosophy and Yoga. Various original texts, commentaries and expositions were written. The main Ācāryas were Samantabhadra, Siddhasena Divākara, Akalanka, Haribhadra, Mānikyanandi, Vidyānandi, Prabhācandra, Hemacandra, Yaśovijaya. For a detailed chronological list of Jain philosopher-monks see Jain Philosophers. It was also a period of formation of modern Jain communities and extensive Jain contribution to Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada, Hindi and Gujarati Literature. |

|

981 CE

|

Construction of Gommaṭeśvara – Statue of Lord Bāhubalī (18 meters- 57 feet, worlds tallest monolithic free standing structure), at Sravana Belagola, Karnataka by Cāmuṇḍarāya, the General-in-chief and Prime Minister of the Gaṅga kings of Mysore. |

|

10th Century CE

|

Emergence of Śvetāmbara Gacchas out of which, most prominent are Tapā Gachha, and Kharatara Gaccha |

|

11th–12th Century CE

|

Construction of Delwara temples at Mount Ābu built by the Jain ministers of the king of Gujarat, Vastupāla and Tejapāla |

|

13th Century CE

|

Emergence of institution of Bhattāraka |

|

1474 CE

|

Establishment of non-image worshipping Śvetāmbara sect of Sthānakvasi established by a Jain layman, Lonka Shah. |

|

1506 CE

|

Establishment of Taranapantha Digambara sect |

|

1683 CE

|

Establishment of Digambara sect of Terapantha by a Śvetāmbara layman, Banarasidas |

|

1760 CE

|

Separation of Ācārya Bhikṣu from Sthānakavasi and establishment of Śvetāmbara Terāpantha sect. |

|

1901 CE

|

Establishment of Kavi Pantha based on the teachings of Srimad Rājacandra (1867 – 1901) |

|

1934 CE

|

Separation of Kānjisvāmi from Sthānakavasi and establishment of Digambara Kānjipantha |

|

Parshvanatha, the twenty-third Tirthankar, is the earliest Jain leader who can be reliably dated. As noted, however, Jain mythology asserts that the line of Tirthankars in the present era began with Rishabhdeva; moreover, Jains themselves believe that Jainism has no single founder, and that it has always existed and will always exist, although it is occasionally forgotten by humans. Emperor Chandragupta Maurya embraced Jainism after retiring. At an older age, Chandragupta renounced his throne and material possessions to join a wandering group of Jain monks. Chandragupta was a disciple of Acharya Bhadrabahu. It is said that in his last days, he observed the rigorous but self purifying Jain ritual of santhara i.e. fast unto death, at Shravana Belagola in Karnataka.

However, his successor, Emperor Bindusara, was a follower of a Hindu ascetic movement, Ajivika and distanced himself from Jain and Buddhist movements. Samprati, the grandson of Ashoka also embraced Jainism. Samrat Samprati was influenced by the teachings of Jain monk Arya Suhasti Suri and he is known[citation needed] to have built 125,000 Jain Temples across India. Some of them are still found in towns of Ahmedabad, Viramgam, Ujjain and Palitana. It is also said that just like Ashoka, Samprati sent messengers & preachers to Greece, Persia & the Middle East to facilitate the spread of Jainism. But to date no research has been done in this area. Thus, Jainism became a vital force under the Mauryan Rule. Chandragupta & Samprati are credited for the spread of Jainism in Southern India. Hundreds of thousands of Jain Temples and Jain Stupas were erected during their reign. But due to lack of royal patronage and its strict principles, along with the rise of Shankaracharya & Ramanujacharya, Jainism, once the major religion of southern India, began to decline.[2][3]

According to scholars, Parshvanath was a historical figure and lived in the 9th century BCE.[52][53] In the 6th century BCE, Vardhamana Mahavira became one of the most influential Jainism teachers. He built up a large group of disciples that learned from his teachings and followed him as he taught an ascetic doctrine in order to achieve enlightenment. The disciples referred to him as Jina, which means "the conqueror" and later his followers would use a derivation of this title to refer to themselves as Jains, a follower of the Jina.[54]

It is generally accepted that Jainism started spreading in south India from the 3rd century BCE. i.e. since the time when Badrabahu, a preacher of this religion and the head of the monks' community, came to Karnataka from Bihar.[55]

Kalinga (modern Orissa/Osiaji) was home to many Jains in the past. Rishabhnath, the first Tirthankar, was revered and worshipped in the ancient city Pithunda, capital of Kalinga. This was destroyed by Mahapadma Nanda when he conquered Kalinga and brought the statue of Rushabhanatha to his capital in Magadh. Rushabhanatha is revered as the Kalinga Jina. Ashoka's invasion and his Buddhist policy also subjugated Jains greatly in Kalinga. However, in the first century BCE Emperor Kharvela conquered Magadha and brought Rishabhnath's statue back and installed it in Udaygiri, near his capital, Shishupalgadh. The Khandagiri and Udaygiri caves near Bhubaneswar are the only surviving stone Jain monuments in Orissa. Earlier buildings were made of wood and were destroyed.

Deciphering of the Brahmi script by James Prinsep in 1788 enabled the reading of ancient inscriptions in India and established the antiquity of Jainism. The discovery of Jain manuscripts has added significantly to retracing Jain history. Archaeologists have encountered Jain remains and artifacts at Maurya, Sunga, Kishan, Gupta, Kalachuries, Rashtrakut, Chalukya, Chandel and Rajput as well as later sites. Several western and Indian scholars have contributed to the reconstruction of Jain history. Western historians like Bühler, Jacobi, and Indian scholars like Iravatham Mahadevan, worked on Tamil Brahmi inscriptions.

Double-sided Leaf from a Chandana Malayaqiri Varta Series ascribed to the artists Karam and Mahata Chandji - 1745. This painting was made for a practitioner of the Jain religion. The image illustrates a Jain text and includes a small shrine with an icon of a Jain savior, known as a Jina or Tirthankara, on the right. The icon sits cross-legged in a meditative posture, and the temple has two white towers of the classic North Indian form. A small pool in front of the temple reflects the surrounding architecture.

This pervasive influence of Jain culture and philosophy in ancient Bihar gave rise to Buddhism. The Buddhists have always maintained that during the time of Buddha and Mahavira (who, according to the Pali canon, were contemporaries), Jainism was already an ancient, deeply entrenched faith and culture there. Over several thousand years, Jain influence on Hindu rituals has been observed and similarly the concept of non-violence has been incorporated into Hinduism. Certain Vedic Hindu holy books contain beautiful narrations about various Jain Tirthankaras (e.g. Lord Rushabdev). In the history of mankind, there have been no wars fought in the name of Jainism.

With 10 to 12 million followers,[56] Jainism is among the smallest of the major world religions, but in India its influence is much greater than these numbers would suggest. Jains live throughout India. Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujarat have the largest Jain populations among Indian states. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Bundelkhand and Madhya Pradesh have relatively large Jain populations. There is a large following in Punjab, especially in Ludhiana and Patiala, and there used to be many Jains in Lahore (Punjab's historic capital) and other cities before the Partition of 1947, after which many fled to India. There are many Jain communities in different parts of India and around the world. They may speak local languages or follow different rituals but essentially they follow the same principles.

Outside India, the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) have large Jain communities. The first Jain temple to be built outside India was constructed and consecrated in the 1960s in Mombasa, Kenya by the local Gujarati Jain community, although Jainism in the West mostly came about after the Oswal and Jain diaspora spread to the West in the late 1970s and 1980s. Jainism is presently a strong faith in the United States, and several dozen Jain temples have been built there, primarily by the Gujarati community. American Jainism accommodates all the sects. Smaller Jain communities exist in Nepal, South Africa, Japan, Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, Fiji, and Suriname. In Belgium, the very successful Indian diamond community in Antwerp, almost all of whom are Jain, opened the largest Jain temple outside India in 2010, to strengthen Jain values in and across Western Europe.

Main articles:

Digambara and

SvetambaraTimeline of various splits in Jainism

The Jain sangha is divided into two major sects, Digambara and Svetambara. The differences in belief between the two sects are minor and relatively obscure. Digambara monks do not wear clothes because they believe clothes, like other possessions, increase dependency and desire for material things, and desire for anything ultimately leads to sorrow. This also restricts full monastic life (and therefore moksa) to males as Digambaras do not permit women to be nude; female renunciates wear white and are referred to as Aryikas. Svetambara monastics, on the other hand, wear white seamless clothes for practical reasons, and believe there is nothing in the scriptures that condemns wearing clothes. Women are accorded full status as renunciates and are often called sadhvi, the feminine of the term often used for male munis, sadhu. Svetambaras believe women may attain liberation and that Mallinath, a Tirthankara, was female.[57]

The earliest record of Digambara beliefs is contained in the Prakrit Suttapahuda of the Digambara mendicant Kundakunda (c. 2nd century AD).[58]

Digambaras believe that Mahavira remained unmarried, whereas Svetambaras believe Mahavira married a woman who bore him a daughter. The two sects also differ on the origin of Mata Trishala, Mahavira's mother. Digambaras believe that only the first five lines are formally part of the Namokar Mantra (the main Jain prayer), whereas Svetambaras believe all nine form the mantra. Other differences are minor and not based on major points of doctrine.

Excavations at Mathura revealed many Jain statues from the time of the Kushan Empire. Tirthankaras, represented without clothes, and monks with cloth wrapped around the left arm are identified as Ardhaphalaka "half-clothed" and mentioned in some texts. The Yapaniyas, believed to have originated from the Ardhaphalaka, followed Digambara nudity, along with several Svetambara beliefs.

Svetambaras sub-sects include Sthanakavasi, Terapanthi, and Murtipujaka. Some revering statues while other Jains are aniconic. Svetambaras follow the 12 agama literature.

Digambara sub-sects include Bisapanthi, Kanjipanthi, Taranapanthi, Terapanthi and Srimadi.

Most simply call themselves Jains and follow general traditions rather than specific sectarian practices. In 1974 a committee with representatives from every sect compiled a new text called the Saman Suttam.

Main article:

Jain symbols

The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes the Jain Vow of Ahimsa, meaning

non-violence. The word in the middle is "

Ahimsa". The wheel represents the

dharmacakra, to halt the cycle of reincarnation through the pursuit of truth

The

swastika is among the holiest of Jain symbols

The

Jain symbol that was agreed upon by all Jain sects in 1974.

- Eight auspicious symbols (The Asta Mangalas). Their names are:

- Swastika - Signifies peace and well-being

- Shrivatsa - A mark manifested on the centre of the Jina's chest, signifying a pure soul.

- Nandyavartya - Large swastika with nine corners

- Vardhamanaka - A shallow earthen dish used for lamps, suggests an increase in wealth, fame and merit due to a Jina's grace.

- Bhadrasana - Throne, considered auspicious because it is sanctified by the blessed Jina's feet.

- Kalasha - Pot filled with pure water signifying wisdom and completeness

- Minayugala - Fish couple. It signfifies conquering over sexual desires

- Darpana - The mirror reflects one's true self because of its clarity

The holiest symbol is a simple swastika. A Jain swastika is normally associated with the three dots on the top accompanied with a crest and a dot.

Other important symbols are:

- Dharma Wheel on the palm of a hand, symbolizing Ahimsa

- 24 Lanchhanas (symbols) of the Tirthankaras. They are in the sequence of the 1st Thirthankara to the 24th are: bull, elephant, horse, monkey, redgoose, lotus flower, swastika, crescent of moon, crocodile, shade providing tree, rhinoceros, buffalo, pig, porcupine, vajra (a kind of weapon), deer, goat, fish, jar, tortoise, lilly flower, conch, snake and lion.

- Triple umbrellas, signifying protection through triple gems of Jainism. The triple umbrella are usually seen with Thirthankar idols

- Dreams of Trishala, 24th Tirthankar's mother prior to giving birth to Mahavir

While Jains represent less than 1% of the Indian constitution and population, their contributions to culture and society in India are extremely significant. Jainism had a major influence in developing a system of philosophy and ethics that had a great impact on all aspects of Indian culture. Scholarly research and evidences have shown that philosophical concepts considered typically Indian – karma, ahimsa, moksa, reincarnation and the like – were propagated and developed by Jain teachers.[59]

Jains have also contributed to the culture and language of the Indian states Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Jain scholars and poets authored Tamil classics of the Sangam period such as the Silappatikaram, Civaka Cintamani, Manimekalai and Nālaṭiyār. In the beginning of the medieval period, between the 9th and 13th centuries, Kannada authors were predominantly of the Jain and Lingayati faiths. Jains were the earliest known cultivators of Kannada literature, which they dominated until the 12th century. Jains wrote about the Tirthankaras and other aspects of the faith. Adikavi Pampa is one of the greatest Kannada poets of all time and was the court poet of Chalukya king Arikesari, a Rashtrakuta feudatory, and is best known for his Vikramarjuna Vijaya. The works of Adikavi Pampa, Ponna and Ranna, collectively called the "three gems of Kannada literature", heralded the age of classical Kannada in the 10th century. The earliest known Gujarati text, Bharata-Bahubali Rasa, was written by a monk. Some important people in Gujarat's history were Acharya Hemachandra and his pupil, the Solanki ruler Kumarpal.

Jains are among the wealthiest Indians. They run numerous schools, colleges and hospitals and are important patrons of the Somapuras, the traditional temple architects in Gujarat. Jains have greatly influenced Gujarati cuisine. Gujarat is predominantly vegetarian (see Jain vegetarianism), and its food is mild as onions and garlic are omitted.

Jains encourage their monks to do research and obtain higher education. Jain monks and nuns, particularly in Rajasthan, have published numerous research monographs. This is unique among Indian religious groups and parallels Christian clergy. The 2001 census states that Jains are India's most literate community and that India's oldest libraries at Patan and Jaisalmer are preserved by Jain institutions.

Jains have contributed to India's classical and popular literature. For example, almost all early Kannada literature and many Tamil works were written by Jains.

- Some of the oldest known books in Hindi and Gujarati were written by Jain scholars. The first autobiography in the ancestor of Hindi, Braj Bhasha, is called Ardhakathānaka and was written by a Jain, Banarasidasa, an ardent follower of Acarya Kundakunda who lived in Agra.

- Many Tamil classics are written by Jains or with Jain beliefs and values as the core subject.

- Practically all the known texts in the Apabhramsha language are Jain works.

The oldest Jain literature is in Shauraseni and the Jain Prakrit (the Jain Agamas, Agama-Tulya, the Siddhanta texts, etc.). Many classical texts are in Sanskrit (Tattvartha Sutra, Puranas, Kosh, Sravakacara, mathematics, Nighantus etc.). "Abhidhana Rajendra Kosha" written by Acharya Rajendrasuri, is only one available Jain encyclopedia or Jain dictionary to understand the Jain Prakrit, Sanskrit, Ardha-Magadhi and other languages, words, their use and references within oldest Jain literature.

Jain literature was written in Apabhraṃśa (Kahas, rasas, and grammars), Standard Hindi (Chhahadhala, Moksh Marg Prakashak, and others), Tamil (Nālaṭiyār, Civaka Cintamani, Valayapathi, and others), and Kannada (Vaddaradhane and various other texts). Jain versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata are found in Sanskrit, the Prakrits, Apabhraṃśa and Kannada.

Jains literature exists mainly in Jain Prakrit, Sanskrit, Marathi, Tamil, Rajasthani, Dhundari, Marwari, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam,[60] Tulu and more recently in English.

In 2005 the Supreme Court of India declined to issue a writ of mandamus towards granting Jains the status of a religious minority throughout India. The Court noted that Jains have been declared a minority in five states already, and left it to the rest of the States to decide on the minority status of Jain religion.[61]

In 2006 the Indian Supreme Court, in a judgment pertaining to an Indian state, opined that "Jain Religion is indisputably not a part of the Hindu Religion".[62]

Jains are not a part of the Vedic Religion (Hinduism).[63][64][65] Ancient India had two philosophical streams of thought: The Shramana philosophical schools, represented by Jainism movement, and the Brahmana/Vedic/Puranic schools represented by Vedanta, Vaishnava and other movements. Both streams have existed side by side for few thousands of years, influencing each other.[66]