Electronic mail, commonly known as email or e-mail, is a method of exchanging digital messages from an author to one or more recipients. Modern email operates across the Internet or other computer networks. Some early email systems required that the author and the recipient both be online at the same time, in common with instant messaging. Today's email systems are based on a store-and-forward model. Email servers accept, forward, deliver and store messages. Neither the users nor their computers are required to be online simultaneously; they need connect only briefly, typically to an email server, for as long as it takes to send or receive messages.

An email message consists of three components, the message ''envelope'', the message ''header'', and the message ''body''. The message header contains control information, including, minimally, an originator's email address and one or more recipient addresses. Usually descriptive information is also added, such as a subject header field and a message submission date/time stamp.

Originally a text-only (7-bit ASCII and others) communications medium, email was extended to carry multi-media content attachments, a process standardized in RFC 2045 through 2049. Collectively, these RFCs have come to be called Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME).

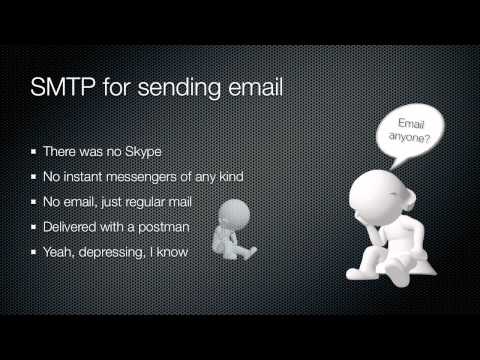

Electronic mail predates the inception of the Internet, and was in fact a crucial tool in creating it, but the history of modern, global Internet email services reaches back to the early ARPANET. Standards for encoding email messages were proposed as early as 1973 (RFC 561). Conversion from ARPANET to the Internet in the early 1980s produced the core of the current services. An email sent in the early 1970s looks quite similar to a basic text message sent on the Internet today.

Network-based email was initially exchanged on the ARPANET in extensions to the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), but is now carried by the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), first published as Internet standard 10 (RFC 821) in 1982. In the process of transporting email messages between systems, SMTP communicates delivery parameters using a message ''envelope'' separate from the message (header and body) itself.

Electronic mail has several English

spelling options that occasionally prove cause for surprisingly vehement disagreement.

''email'' is the form required by IETF Requests for Comment and working groups and increasingly by style guides. This spelling also appears in most dictionaries.

''e-mail'' is a form previously recommended by some prominent journalistic and technical style guides. According to Corpus of Contemporary American English data, this is the form that appears most frequently in edited, published American English writing.

''mail'' was the form used in the original RFC. The service is referred to as ''mail'' and a single piece of electronic mail is called a ''message''.

''eMail'', capitalizing only the letter ''M'', was common among ARPANET users and the early developers of Unix, CMS, AppleLink, eWorld, AOL, GEnie, and Hotmail.

''EMail'' is a traditional form that has been used in RFCs for the "Author's Address", and is expressly required "for historical reasons".

''E-mail'' is sometimes used, capitalizing the initial letter ''E'' as in similar abbreviations like ''E-piano'', ''E-guitar'', ''A-bomb'', ''H-bomb'', and ''C-section''.

There is also some variety in the plural form of the term. In US English ''email'' is used as a mass noun (like the term ''mail'' for items sent through the postal system), but in British English it is more commonly used as a count noun with the plural ''emails''.

Sending text messages electronically could be said to date back to the

Morse code telegraph of the mid 1800s; and the

1939 New York World's Fair, where

IBM sent a letter of congratulations from San Francisco to New York on an IBM radio-type, calling it a high-speed substitute for mail service in the world of tomorrow.

Teleprinters were used in Germany during World War II, and use spread until the late 1960s when there was a worldwide

Telex network. Additionally, there was the similar but incompatible

American TWX, which remained important until the late 1980s.

With the introduction of

MIT's

Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) in 1961 for the first time multiple users were able to log into a central system from remote dial-up terminals, and to store, and share, files on the central disk. Informal methods of using this to pass messages developed—and were expanded to create the first true email system:

MIT's

CTSS MAIL, in 1965.

Other early time-sharing system soon had their own email applications:

1972 - Unix mail program

1972 - APL Mailbox by Larry Breed

1981 - PROFS by IBM

1982 - ALL-IN-1 by Digital Equipment Corporation

Although similar in concept, all these original email systems had widely different features and ran on incompatible systems. They allowed communication only between users logged into the same host or "mainframe" - although this could be hundreds or even thousands of users within an organization.

Soon systems were developed to link compatible mail programs between different organisations over dialup modems or leased lines, creating local and global networks.

In 1971 the first ARPANET email was sent, and through RFC 561, RFC 680, RFC 724—and finally 1977's RFC 733, became a standardized working system.

Other separate networks were also being created including:

Unix mail was networked by 1978's uucp, which was also used for USENET newsgroup postings

IBM mainframe email was linked by BITNET in 1981

IBM PCs running DOS in 1984 could link with FidoNet for email and shared bulletin board posting

In the early 1980s, networked

personal computers on

LANs became increasingly important. Server-based systems similar to the earlier mainframe systems were developed. Again these systems initially allowed communication only between users logged into the same server infrastructure. Examples include:

cc:Mail

Lantastic

WordPerfect Office

Microsoft Mail

Banyan VINES

Lotus Notes

Eventually these systems too could also be linked between different organizations, as long as they ran the same email system and proprietary protocol.

Early interoperability among independent systems included:

ARPANET, the forerunner of today's Internet, defined the first protocols for dissimilar computers to exchange email

uucp implementations for non-Unix systems were used as an open "glue" between differing mail systems, primarily over dialup telephones

CSNet used dial-up telephone access to link additional sites to the ARPANET and then Internet

Later efforts at interoperability standardization included:

Novell briefly championed the open MHS protocol but abandoned it after purchasing the non-MHS WordPerfect Office (renamed Groupwise)

The Coloured Book protocols on UK academic networks until 1992

X.400 in the 1980s and early 1990s was promoted by major vendors and mandated for government use under GOSIP but abandoned by all but a few — in favor of Internet SMTP by the mid-1990s.

In the early 1970s, Ray Tomlinson updated an existing utility called

SNDMSG so that it could copy messages (as files) over the network.

Lawrence Roberts, the project manager for the ARPANET development, took the idea of READMAIL, which dumped all "recent" messages onto the user's terminal, and wrote a program for

TENEX in

TECO macros called RD which permitted accessing individual messages. Barry Wessler then updated RD and called it NRD.

Marty Yonke combined rewrote NRD to include reading, access to SNDMSG for sending, and a help system, and called the utility WRD which was later known as BANANARD. John Vittal then updated this version to include 3 important commands: ''Move'' (combined save/delete command), ''Answer'' (determined to whom a reply should be sent) and ''Forward'' (send an email to a person who was not already a recipient). The system was called MSG. With inclusion of these features, MSG is considered to be the first integrated modern email program, from which many other applications have descended.

The ARPANET

computer network made a large contribution to the development of email. There is one report that indicates experimental inter-system email transfers began shortly after its creation in 1969.

Ray Tomlinson is generally credited as having sent the first email across a network, initiating the use of the "

@" sign to separate the names of the user and the user's machine in 1971, when he sent a message from one

Digital Equipment Corporation DEC-10 computer to another DEC-10. The two machines were placed next to each other. Tomlinson's work was quickly adopted across the ARPANET, which significantly increased the popularity of email. For many years, email was the

killer app of the ARPANET and then the Internet.

Most other networks had their own email protocols and address formats; as the influence of the ARPANET and later the Internet grew, central sites often hosted email gateways that passed mail between the Internet and these other networks. Internet email addressing is still complicated by the need to handle mail destined for these older networks. Some well-known examples of these were UUCP (mostly Unix computers), BITNET (mostly IBM and VAX mainframes at universities), FidoNet (personal computers), DECNET (various networks) and CSNET a forerunner of NSFNet.

An example of an Internet email address that routed mail to a user at a UUCP host:

hubhost!middlehost!edgehost!user@uucpgateway.somedomain.example.com

This was necessary because in early years UUCP computers did not maintain (and could not consult central servers for) information about the location of all hosts they exchanged mail with, but rather only knew how to communicate with a few network neighbors; email messages (and other data such as Usenet News) were passed along in a chain among hosts who had explicitly agreed to share data with each other. (Eventually the UUCP Mapping Project would provide a form of network routing database for email.)

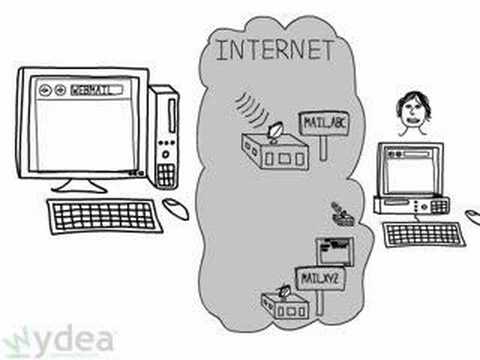

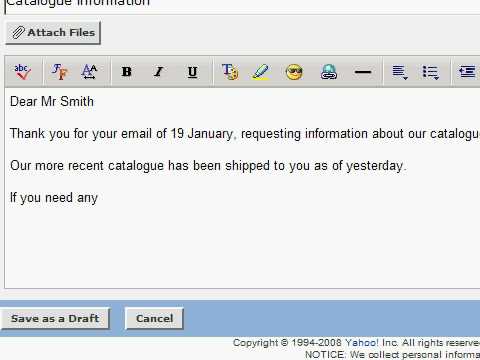

The diagram to the right shows a typical sequence of events that takes place when

Alice composes a message using her

mail user agent (MUA). She enters the

email address of her correspondent, and hits the "send" button.

400px|How email works

# Her MUA formats the message in email format and uses the Submission Protocol (a profile of the

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), see RFC 6409) to send the message to the local

mail submission agent (MSA), in this case

smtp.a.org, run by Alice's

internet service provider (ISP).

# The MSA looks at the destination address provided in the SMTP protocol (not from the message header), in this case

bob@b.org. An Internet email address is a string of the form

localpart@exampledomain. The part before the @ sign is the ''local part'' of the address, often the

username of the recipient, and the part after the @ sign is a

domain name or a

fully qualified domain name. The MSA resolves a domain name to determine the fully qualified domain name of the

mail exchange server in the

Domain Name System (DNS).

# The

DNS server for the

b.org domain,

ns.b.org, responds with any

MX records listing the mail exchange servers for that domain, in this case

mx.b.org, a

message transfer agent (MTA) server run by Bob's ISP.

#

smtp.a.org sends the message to

mx.b.org using SMTP.

This server may need to forward the message to other MTAs before the message reaches the final

message delivery agent (MDA).

# The MDA delivers it to the

mailbox of the user

bob.

# Bob presses the "get mail" button in his MUA, which picks up the message using either the

Post Office Protocol (POP3) or the

Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP4).

That sequence of events applies to the majority of email users. However, there are many alternative possibilities and complications to the email system:

Alice or Bob may use a client connected to a corporate email system, such as IBM Lotus Notes or Microsoft Exchange. These systems often have their own internal email format and their clients typically communicate with the email server using a vendor-specific, proprietary protocol. The server sends or receives email via the Internet through the product's Internet mail gateway which also does any necessary reformatting. If Alice and Bob work for the same company, the entire transaction may happen completely within a single corporate email system.

Alice may not have a MUA on her computer but instead may connect to a webmail service.

Alice's computer may run its own MTA, so avoiding the transfer at step 1.

Bob may pick up his email in many ways, for example logging into mx.b.org and reading it directly, or by using a webmail service.

Domains usually have several mail exchange servers so that they can continue to accept mail when the main mail exchange server is not available.

Email messages are not secure if email encryption is not used correctly.

Many MTAs used to accept messages for any recipient on the Internet and do their best to deliver them. Such MTAs are called ''open mail relays''. This was very important in the early days of the Internet when network connections were unreliable. If an MTA couldn't reach the destination, it could at least deliver it to a relay closer to the destination. The relay stood a better chance of delivering the message at a later time. However, this mechanism proved to be exploitable by people sending unsolicited bulk email and as a consequence very few modern MTAs are open mail relays, and many MTAs don't accept messages from open mail relays because such messages are very likely to be spam.

Message format

The Internet email message format is now defined by RFC 5322, with multi-media content attachments being defined in RFC 2045 through RFC 2049, collectively called ''

Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions'' or ''MIME''. RFC 5322 replaced the earlier RFC 2822 in 2008, and in turn RFC 2822 in 2001 replaced RFC 822 - which had been the standard for Internet email for nearly 20 years. Published in 1982, RFC 822 was based on the earlier RFC 733 for the

ARPANET.

Internet email messages consist of two major sections:

''Header'' — Structured into fields such as From, To, CC, Subject, Date, and other information about the email.

''Body'' — The basic content, as unstructured text; sometimes containing a signature block at the end. This is exactly the same as the body of a regular letter.

The header is separated from the body by a blank line.

Each message has exactly one

header, which is structured into

fields. Each field has a name and a value. RFC 5322 specifies the precise syntax.

Informally, each line of text in the header that begins with a printable character begins a separate field. The field name starts in the first character of the line and ends before the separator character ":". The separator is then followed by the field value (the "body" of the field). The value is continued onto subsequent lines if those lines have a space or tab as their first character. Field names and values are restricted to 7-bit ASCII characters. Non-ASCII values may be represented using MIME encoded words.

Email header fields can be multi-line, and each line must be at most 76 characters long. Header fields can only contain

US-ASCII characters; for encoding characters in other sets, a syntax specified in RFC 2047 can be used. Recently the IETF EAI working group has defined some experimental extensions to allow

Unicode characters to be used within the header. In particular, this allows email addresses to use non-ASCII characters. Such characters must only be used by servers that support these extensions.

The message header must include at least the following fields:

''From'': The email address, and optionally the name of the author(s). In many email clients not changeable except through changing account settings.

''Date'': The local time and date when the message was written. Like the ''From:'' field, many email clients fill this in automatically when sending. The recipient's client may then display the time in the format and time zone local to him/her.

The message header should include at least the following fields:

''Message-ID'': Also an automatically generated field; used to prevent multiple delivery and for reference in In-Reply-To: (see below).

''In-Reply-To'': Message-ID of the message that this is a reply to. Used to link related messages together. This field only applies for reply messages.

RFC 3864 describes registration procedures for message header fields at the IANA; it provides for permanent and provisional message header field names, including also fields defined for MIME, netnews, and http, and referencing relevant RFCs. Common header fields for email include:

''To'': The email address(es), and optionally name(s) of the message's recipient(s). Indicates primary recipients (multiple allowed), for secondary recipients see Cc: and Bcc: below.

''Subject'': A brief summary of the topic of the message. Certain abbreviations are commonly used in the subject, including "RE:" and "FW:".

''Bcc'': Blind Carbon Copy; addresses added to the SMTP delivery list but not (usually) listed in the message data, remaining invisible to other recipients.

''Cc'': Carbon copy; Many email clients will mark email in your inbox differently depending on whether you are in the To: or Cc: list.

Content-Type: Information about how the message is to be displayed, usually a MIME type.

''Precedence'': commonly with values "bulk", "junk", or "list"; used to indicate that automated "vacation" or "out of office" responses should not be returned for this mail, e.g. to prevent vacation notices from being sent to all other subscribers of a mailinglist.

Sendmail uses this header to affect prioritization of queued email, with "Precedence: special-delivery" messages delivered sooner. With modern high-bandwidth networks delivery priority is less of an issue than it once was.

Microsoft Exchange respects a fine-grained automatic response suppression mechanism, the X-Auto-Response-Suppress header.

''References'': Message-ID of the message that this is a reply to, and the message-id of the message the previous reply was a reply to, etc.

''Reply-To'': Address that should be used to reply to the message.

''Sender'': Address of the actual sender acting on behalf of the author listed in the From: field (secretary, list manager, etc.).

''Archived-At'': A direct link to the archived form of an individual email message.

Note that the ''To:'' field is not necessarily related to the addresses to which the message is delivered. The actual delivery list is supplied separately to the transport protocol, SMTP, which may or may not originally have been extracted from the header content. The "To:" field is similar to the addressing at the top of a conventional letter which is delivered according to the address on the outer envelope. In the same way, the "From:" field does not have to be the real sender of the email message. Some mail servers apply email authentication systems to messages being relayed. Data pertaining to server's activity is also part of the header, as defined below.

SMTP defines the ''trace information'' of a message, which is also saved in the header using the following two fields:

''Received'': when an SMTP server accepts a message it inserts this trace record at the top of the header (last to first).

''Return-Path'': when the delivery SMTP server makes the ''final delivery'' of a message, it inserts this field at the top of the header.

Other header fields that are added on top of the header by the receiving server may be called ''trace fields'', in a broader sense.

''Authentication-Results'': when a server carries out authentication checks, it can save the results in this field for consumption by downstream agents.

''Received-SPF'': stores the results of SPF checks.

''Auto-Submitted'': is used to mark automatically generated messages.

''VBR-Info'': claims VBR whitelisting

Email was originally designed for 7-bit

ASCII. Most email software is

8-bit clean but must assume it will communicate with 7-bit servers and mail readers. The

MIME standard introduced character set specifiers and two content transfer encodings to enable transmission of non-ASCII data:

quoted printable for mostly 7 bit content with a few characters outside that range and

base64 for arbitrary binary data. The

8BITMIME and

BINARY extensions were introduced to allow transmission of mail without the need for these encodings, but many

mail transport agents still do not support them fully. In some countries, several encoding schemes coexist; as the result, by default, the message in a non-Latin alphabet language appears in non-readable form (the only exception is coincidence, when the sender and receiver use the same encoding scheme). Therefore, for international

character sets,

Unicode is growing in popularity.

Most modern graphic

email clients allow the use of either

plain text or

HTML for the message body at the option of the user.

HTML email messages often include an automatically generated plain text copy as well, for compatibility reasons.

Advantages of HTML include the ability to include in-line links and images, set apart previous messages in block quotes, wrap naturally on any display, use emphasis such as underlines and italics, and change font styles. Disadvantages include the increased size of the email, privacy concerns about web bugs, abuse of HTML email as a vector for phishing attacks and the spread of malicious software.

Some web based Mailing lists recommend that all posts be made in plain-text, with 72 or 80 characters per line for all the above reasons, but also because they have a significant number of readers using text-based email clients such as Mutt.

Some Microsoft email clients allow rich formatting using RTF, but unless the recipient is guaranteed to have a compatible email client this should be avoided.

In order to ensure that HTML sent in an email is rendered properly by the recipient's client software, an additional header must be specified when sending: "Content-type: text/html". Most email programs send this header automatically.

Messages are exchanged between hosts using the

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol with software programs called

mail transfer agents (MTAs); and delivered to a mail store by programs called

mail delivery agents (MDAs, also sometimes called local delivery agents, LDAs). Users can retrieve their messages from servers using standard protocols such as

POP or

IMAP, or, as is more likely in a large

corporate environment, with a

proprietary protocol specific to

Novell Groupwise,

Lotus Notes or

Microsoft Exchange Servers. Webmail interfaces allow users to access their mail with any standard

web browser, from any computer, rather than relying on an email client. Programs used by users for retrieving, reading, and managing email are called

mail user agents (MUAs).

Mail can be stored on the client, on the server side, or in both places. Standard formats for mailboxes include Maildir and mbox. Several prominent email clients use their own proprietary format and require conversion software to transfer email between them. Server-side storage is often in a proprietary format but since access is through a standard protocol such as IMAP, moving email from one server to another can be done with any MUA supporting the protocol.

Accepting a message obliges an MTA to deliver it, and when a message cannot be delivered, that MTA must send a bounce message back to the sender, indicating the problem.

Upon reception of email messages,

email client applications save messages in operating system files in the file system. Some clients save individual messages as separate files, while others use various database formats, often proprietary, for collective storage. A historical standard of storage is the ''

mbox'' format. The specific format used is often indicated by special

filename extensions:

;

eml

:Used by many email clients including

Microsoft Outlook Express,

Windows Mail and

Mozilla Thunderbird. The files are

plain text in

MIME format, containing the email header as well as the message contents and attachments in one or more of several formats.

;

emlx

:Used by

Apple Mail.

;

msg

:Used by

Microsoft Office Outlook and

OfficeLogic Groupware.

;

mbx

:Used by

Opera Mail,

KMail, and

Apple Mail based on the

mbox format.

Some applications (like Apple Mail) leave attachments encoded in messages for searching while also saving separate copies of the attachments. Others separate attachments from messages and save them in a specific directory.

The

URI scheme, as registered with the

IANA, defines the

mailto: scheme for SMTP email addresses. Though its use is not strictly defined, URLs of this form are intended to be used to open the new message window of the user's mail client when the URL is activated, with the address as defined by the URL in the ''To:'' field.

There are numerous ways in which people have changed the way they communicate in the last 50 years; email is certainly one of them. Traditionally, social interaction in the local community was the basis for communication – face to face. Yet, today face-to-face meetings are no longer the primary way to communicate as one can use a

landline telephone,

mobile phones,

fax services, or any number of the computer mediated communications such as email.

Flaming occurs when a person sends a message with angry or antagonistic content. The term is derived from the use of the word Incendiary to describe particularly heated email discussions. Flaming is assumed to be more common today because of the ease and impersonality of email communications: confrontations in person or via telephone require direct interaction, where social norms encourage civility, whereas typing a message to another person is an indirect interaction, so civility may be forgotten. Flaming is generally looked down upon by Internet communities as it is considered rude and non-productive.

Also known as "email fatigue", email bankruptcy is when a user ignores a large number of email messages after falling behind in reading and answering them. The reason for falling behind is often due to information overload and a general sense there is so much information that it is not possible to read it all. As a solution, people occasionally send a boilerplate message explaining that the email inbox is being cleared out.

Harvard University law professor

Lawrence Lessig is credited with coining this term, but he may only have popularized it.

Email was widely accepted by the business community as the first broad electronic communication medium and was the first ‘e-revolution’ in business communication. Email is very simple to understand and like postal mail, email solves two basic problems of communication: logistics and synchronization (see below).

LAN based email is also an emerging form of usage for business. It not only allows the business user to download mail when ''offline'', it also allows the small business user to have multiple users' email IDs with just ''one email connection''.

''The problem of logistics'': Much of the business world relies upon communications between people who are not physically in the same building, area or even country; setting up and attending an in-person meeting, telephone call, or conference call can be inconvenient, time-consuming, and costly. Email provides a way to exchange information between two or more people with no set-up costs and that is generally far less expensive than physical meetings or phone calls.

''The problem of synchronisation'': With real time communication by meetings or phone calls, participants have to work on the same schedule, and each participant must spend the same amount of time in the meeting or call. Email allows asynchrony: each participant may control their schedule independently.

Most business workers today spend from one to two hours of their working day on email: reading, ordering, sorting, ‘re-contextualizing’ fragmented information, and writing email. The use of email is increasing due to increasing levels of globalisation—labour division and outsourcing amongst other things. Email can lead to some well-known problems:

''Loss of context'': which means that the context is lost forever; there is no way to get the text back. Information in context (as in a newspaper) is much easier and faster to understand than unedited and sometimes unrelated fragments of information. Communicating in context can only be achieved when both parties have a full understanding of the context and issue in question.

''Information overload'': Email is a push technology—the sender controls who receives the information. Convenient availability of mailing lists and use of "copy all" can lead to people receiving unwanted or irrelevant information of no use to them.

''Inconsistency'': Email can duplicate information. This can be a problem when a large team is working on documents and information while not in constant contact with the other members of their team.

''Liability''. Statements made in an email can be deemed legally binding and be used against a party in a court of law.

Despite these disadvantages, email has become the most widely used medium of communication within the business world. In fact, a 2010 study on workplace communication, found that 83% of U.S. knowledge workers felt that email was critical to their success and productivity at work.

Email messages may have one or more attachments. Attachments serve the purpose of delivering binary or text files of unspecified size. In principle there is no technical intrinsic restriction in the SMTP protocol limiting the size or number of attachments. In practice, however, email service providers implement various limitations on the permissible size of files or the size of an entire message.

Furthermore, due to technical reasons, often a small attachment can increase in size when sent, which can be confusing to senders when trying to assess whether they can or cannot send a file by email, and this can result in their message being rejected.

As larger and larger file sizes are being created and traded, many users are either forced to upload and download their files using an FTP server, or more popularly, use online file sharing facilities or services, usually over web-friendly HTTP, in order to send and receive them.

A December 2007

New York Times blog post described information overload as "a $650 Billion Drag on the Economy", and the New York Times reported in April 2008 that "E-MAIL has become the bane of some people’s professional lives" due to information overload, yet "none of the current wave of high-profile Internet start-ups focused on email really eliminates the problem of email overload because none helps us prepare replies". GigaOm posted a similar article in September 2010,

highlighting research that found 57% of knowledge workers were overwhelmed by the volume of email they received. Technology investors reflect similar concerns.

In October 2010, CNN published an article titled "Happy Information Overload Day" that compiled research on email overload from IT companies and productivity experts. According to Basex, the average knowledge worker receives 93 emails a day. Subsequent studies have reported higher numbers. Marsha Egan, an email productivity expert, called email technology both a blessing and a curse in the article. She stated, "Everyone just learns that they have to have it dinging and flashing and open just in case the boss e-mails," she said. "The best gift any group can give each other is to never use e-mail urgently. If you need it within three hours, pick up the phone."

The usefulness of email is being threatened by four phenomena:

email bombardment,

spamming,

phishing, and

email worms.

Spamming is unsolicited commercial (or bulk) email. Because of the minuscule cost of sending email, spammers can send hundreds of millions of email messages each day over an inexpensive Internet connection. Hundreds of active spammers sending this volume of mail results in information overload for many computer users who receive voluminous unsolicited email each day.

Email worms use email as a way of replicating themselves into vulnerable computers. Although the first email worm affected UNIX computers, the problem is most common today on the more popular Microsoft Windows operating system.

The combination of spam and worm programs results in users receiving a constant drizzle of junk email, which reduces the usefulness of email as a practical tool.

A number of anti-spam techniques mitigate the impact of spam. In the United States, U.S. Congress has also passed a law, the Can Spam Act of 2003, attempting to regulate such email. Australia also has very strict spam laws restricting the sending of spam from an Australian ISP, but its impact has been minimal since most spam comes from regimes that seem reluctant to regulate the sending of spam.

Email spoofing occurs when the header information of an email is altered to make the message appear to come from a known or trusted source. It is often used as a ruse to collect personal information.

Email bombing is the intentional sending of large volumes of messages to a target address. The overloading of the target email address can render it unusable and can even cause the mail server to crash.

Today it can be important to distinguish between Internet and internal email systems. Internet email may travel and be stored on networks and computers without the sender's or the recipient's control. During the transit time it is possible that third parties read or even modify the content. Internal mail systems, in which the information never leaves the organizational network, may be more secure, although information technology personnel and others whose function may involve monitoring or managing may be accessing the email of other employees.

Email privacy, without some security precautions, can be compromised because:

email messages are generally not encrypted.

email messages have to go through intermediate computers before reaching their destination, meaning it is relatively easy for others to intercept and read messages.

many Internet Service Providers (ISP) store copies of email messages on their mail servers before they are delivered. The backups of these can remain for up to several months on their server, despite deletion from the mailbox.

the "Received:"-fields and other information in the email can often identify the sender, preventing anonymous communication.

There are cryptography applications that can serve as a remedy to one or more of the above. For example, Virtual Private Networks or the Tor anonymity network can be used to encrypt traffic from the user machine to a safer network while GPG, PGP, SMEmail, or S/MIME can be used for end-to-end message encryption, and SMTP STARTTLS or SMTP over Transport Layer Security/Secure Sockets Layer can be used to encrypt communications for a single mail hop between the SMTP client and the SMTP server.

Additionally, many mail user agents do not protect logins and passwords, making them easy to intercept by an attacker. Encrypted authentication schemes such as SASL prevent this.

Finally, attached files share many of the same hazards as those found in peer-to-peer filesharing. Attached files may contain trojans or viruses.

The original SMTP mail service provides limited mechanisms for tracking a transmitted message, and none for verifying that it has been delivered or read. It requires that each mail server must either deliver it onward or return a failure notice (bounce message), but both software bugs and system failures can cause messages to be lost. To remedy this, the

IETF introduced

Delivery Status Notifications (delivery receipts) and

Message Disposition Notifications (return receipts); however, these are not universally deployed in production. (A complete Message Tracking mechanism was also defined, but it never gained traction; see RFCs 3885 through 3888.)

Many ISPs now deliberately disable non-delivery reports (NDRs) and delivery receipts due to the activities of spammers:

Delivery Reports can be used to verify whether an address exists and so is available to be spammed

If the spammer uses a forged sender email address (email spoofing), then the innocent email address that was used can be flooded with NDRs from the many invalid email addresses the spammer may have attempted to mail. These NDRs then constitute spam from the ISP to the innocent user

There are a number of systems that allow the sender to see if messages have been opened. The receiver could also let the sender know that the emails have been opened through an "Okay" button. A check sign can appear in the sender's screen when the receiver's "Okay" button is pressed.

The US Government has been involved in email in several different ways.

Starting in 1977, the US Postal Service (USPS) recognized that electronic mail and electronic transactions posed a significant threat to First Class mail volumes and revenue. Therefore, the USPS initiated an experimental email service known as E-COM. Electronic messages were transmitted to a post office, printed out, and delivered as hard copy. To take advantage of the service, an individual had to transmit at least 200 messages. The delivery time of the messages was the same as First Class mail and cost 26 cents. Both the Postal Regulatory Commission and the Federal Communications Commission opposed E-COM. The FCC concluded that E-COM constituted common carriage under its jurisdiction and the USPS would have to file a tariff. Three years after initiating the service, USPS canceled E-COM and attempted to sell it off.

The early ARPANET dealt with multiple email clients that had various, and at times incompatible, formats. For example, in the Multics, the "@" sign meant "kill line" and anything before the "@" sign was ignored, so Multics users had to use a command-line option to specify the destination system. The Department of Defense DARPA desired to have uniformity and interoperability for email and therefore funded efforts to drive towards unified inter-operable standards. This led to David Crocker, John Vittal, Kenneth Pogran, and Austin Henderson publishing RFC 733, "Standard for the Format of ARPA Network Text Message" (November 21, 1977), which was apparently not effective. In 1979, a meeting was held at BBN to resolve incompatibility issues. Jon Postel recounted the meeting in RFC 808, "Summary of Computer Mail Services Meeting Held at BBN on 10 January 1979" (March 1, 1982), which includes an appendix listing the varying email systems at the time. This, in turn, lead to the release of David Crocker's RFC 822, "Standard for the Format of ARPA Internet Text Messages" (August 13, 1982).

The National Science Foundation took over operations of the ARPANET and Internet from the Department of Defense, and initiated NSFNet, a new backbone for the network. A part of the NSFNet AUP forbade commercial traffic. In 1988, Vint Cerf arranged for an interconnection of MCI Mail with NSFNET on an experimental basis. The following year Compuserve email interconnected with NSFNET. Within a few years the commercial traffic restriction was removed from NSFNETs AUP, and NSFNET was privatised.

In the late 1990s, the Federal Trade Commission grew concerned with fraud transpiring in email, and initiated a series of procedures on spam, fraud, and phishing. In 2004, FTC jurisdiction over spam was codified into law in the form of the CAN SPAM Act. Several other US Federal Agencies have also exercised jurisdiction including the Department of Justice and the Secret Service.

NASA has provided email capabilities to astronauts aboard the Space Shuttle and International Space Station since 1991 when a Macintosh Portable was used aboard Space Shuttle mission STS-43 to send the first email via AppleLink. Today astronauts aboard the International Space Station have email capabilities through the via wireless networking throughout the station and are connected to the ground at 3 Mbit/s Earth to station and 10 Mbit/s station to Earth, comparable to home DSL connection speeds.

Email encryption

HTML email

Internet fax

Privacy-enhanced Electronic Mail

Push email

X-Originating-IP

Anti-spam techniques (email)

CompuServe (first consumer service)

Computer virus

E-card

Email art

Email jamming

Email spam

Email spoofing

Email storm

List of email subject abbreviations

Information overload

Internet humor

Internet slang

Netiquette

Posting style

Usenet quoting

Biff

Email address

Email authentication

Email client, Comparison of email clients

Email hosting service

Internet mail standards

Mail transfer agent

Mail user agent

Unicode and email

Webmail

Anonymous remailer

Disposable email address

Email digest

Email encryption

Email tracking

Electronic mailing list

Mailer-Daemon

Mailing list archive

Telegraphy

Lexigram

MCI Mail

IMAP

POP3

SMTP

UUCP

X400

Cemil Betanov, ''Introduction to X.400'', Artech House, ISBN 0-89006-597-7.

Marsha Egan, "Inbox Detox and The Habit of Email Excellence", Acanthus Publishing ISBN 978-0981558981

Lawrence Hughes, ''Internet e-mail Protocols, Standards and Implementation'', Artech House Publishers, ISBN 0-89006-939-5.

Kevin Johnson, ''Internet Email Protocols: A Developer's Guide'', Addison-Wesley Professional, ISBN 0-201-43288-9.

Pete Loshin, ''Essential Email Standards: RFCs and Protocols Made Practical'', John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-34597-0.

Sara Radicati, ''Electronic Mail: An Introduction to the X.400 Message Handling Standards'', Mcgraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-051104-7.

John Rhoton, ''Programmer's Guide to Internet Mail: SMTP, POP, IMAP, and LDAP'', Elsevier, ISBN 1-55558-212-5.

John Rhoton, ''X.400 and SMTP: Battle of the E-mail Protocols'', Elsevier, ISBN 1-55558-165-X.

David Wood, ''Programming Internet Mail'', O'Reilly, ISBN 1-56592-479-7.

Yoram M. Kalman & Sheizaf Rafaeli, Online Pauses and Silence: Chronemic Expectancy Violations in Written Computer-Mediated Communication, ''Communication Research'', Vol. 38, pp. 54–69, 2011

IANA's list of standard header fields

The History of Electronic Mail is a personal memoir by the implementer of an early email system

The Official MCI Mail Blog! a blog about MCI Mail, one of the early commercial electronic mail services

Category:Email

Category:Internet terminology

Category:American inventions

Category:Electronic documents

Category:History of the Internet

af:E-pos

ar:بريد إلكتروني

an:Correu electronico

ast:Corréu electrónicu

az:Elektron poçt

bn:ই-মেইল

zh-min-nan:Tiān-chú-phoe

be:Электронная пошта

be-x-old:Электронная пошта

bg:Електронна поща

bar:E-Post

bo:གློག་རྡུལ་འཕྲིན་སྒམ།

bs:Email

br:Anvonerezh elektronek

ca:Correu electrònic

cv:Электронлă почта

cs:E-mail

cy:E-bost

da:E-mail

de:E-Mail

et:E-kiri

el:Ηλεκτρονικό ταχυδρομείο

es:Correo electrónico

eo:Retpoŝto

eu:Posta elektroniko

fa:رایانامه

fo:Teldupostur

fr:Courrier électronique

fy:E-mail

fur:Pueste eletroniche

ga:Ríomhphost

gl:Correo electrónico

gan:電郵

gu:ઇ-મેઇલ

ko:전자 우편

hy:Էլեկտրոնային փոստ

hi:ईमेल

hr:Elektronička pošta

id:Surat elektronik

is:Tölvupóstur

it:Posta elettronica

he:דואר אלקטרוני

jv:Layang èlèktronik

kn:ಇ-ಅಂಚೆ

ka:ელექტრონული ფოსტა

kk:Электронды пошта

ku:E-peyam

lo:ອີແມລ

la:Cursus electronicus

lv:E-pasts

lt:Elektroninis paštas

li:E-mail

ln:Nkandá

lmo:E-mail

hu:E-mail

mk:Електронско писмо

ml:ഇ-മെയിൽ

mr:ईमेल

ms:Mel elektronik

mn:Цахим шуудан

my:E-Mail

nah:E-mail

nl:E-mail

nds-nl:Lienpost

ne:इमेल

ja:電子メール

no:E-post

nn:E-post

oc:Corrièr electronic

mhr:Электрон почто

uz:E-Mail

pnb:ای میل

ps:برېښليک

tpi:Imel

nds:Nettbreef

pl:Poczta elektroniczna

pt:E-mail

ro:E-mail

rm:E-mail

qu:E-chaski

rue:Електронічна пошта

ru:Электронная почта

sah:E-mail

sq:Posta elektronike

scn:E-mail

si:විද්යුත් තැපෑල

simple:E-mail

sk:E-mail

sl:Elektronska pošta

ckb:پۆستی ئەلەکترۆنی

sr:Електронска пошта

sh:E-mail

su:Surélék

fi:Sähköposti

sv:E-post

tl:Elektronikong liham

ta:மின்னஞ்சல்

te:ఈ-మెయిల్

th:อีเมล

tr:Elektronik posta

uk:Електронна пошта

ur:برقی ڈاک

vec:Posta ełetrònega

vi:Thư điện tử

fiu-vro:Välkpost

wa:Emile

war:E-mail

yi:בליצפאסט

zh-yue:電郵

diq:E-mail

bat-smg:Alektruonėnis pašts

zh:电子邮件