One time return to blogging

My post on the G-20′s agenda can be found on the official Pittsburgh Summit blog.

My post on the G-20′s agenda can be found on the official Pittsburgh Summit blog.

This will be my last blog post, at least for the foreseeable future.

I have accepted a new job, one that will require a certain level of discretion. I am excited by its challenges: ‘Balanced and sustainable” growth is something that I believe in. But suspending this blog is still hard.

I started blogging almost five years ago, back when blogging felt new and the barriers to entry were much lower. I was also lucky: first Nouriel Roubini and RGE and then the CFR were willing to pay me to, at least in part, write a niche blog on global imbalances and global capital flows. The CFR in general – and Richard Haass and Sebastian Mallaby in particular – took a risk (a calculated risk?) that I could maintain a blog with open comments that could live up to the standards of the Council on Foreign Relations.

I started writing a blog almost by default. There wasn’t an obvious source of demand for the kind of work that I wanted to do. My interests were too grounded in current events to fit well with academia, as I neither am a true economist nor a true political scientist. And I was too interested in policy issues to match, consistently, the interests of the market — especially as I am a bit better at seeing risks than opportunities. No private bank keeps a specialist on the TIC data on their payroll.

Plus writing a blog gave me the freedom to write what I wanted when I wanted – and on occasion to work from where I wanted to work.

Over time, I devoted more time to the blog and less to more academic publications than I should have. Blog posts “decay” faster than academic papers. At the same time, all my short-term incentives worked the other way: this blog’s traffic was never was all that high, but it still attracted more readers in an average week than have bought the book I wrote together with Dr. Roubini – and more readers than downloaded the paper I wrote exploring the strategic consequences of relying on foreign governments for financing.

Moreover, there is no other way that my work would have come to the attention of a Nobel Laureate in economics, Berkeley’s economics department (or at least parts of it), a tenured professor of political science, the World Bank’s Beijing office, parts of Deutsche Bank’s research group and the economic quants over at Econbrowser. Or, among many others, an experienced bond market hand, a London-based currency trader, a Beijing-based emerging markets guru, an informed critic of the financial sector and a former professional Fedwatcher turned amateur Fedwatcher.* And a host of financial journalists around the world. The ability to try to hash out, in real time, crucial questions with true experts is the great advantage of the web.

This blog also had the unexpected virtue of making my work accessible to my parents, and convincing them – scientists both – that I did some real work, at least on occasion.**

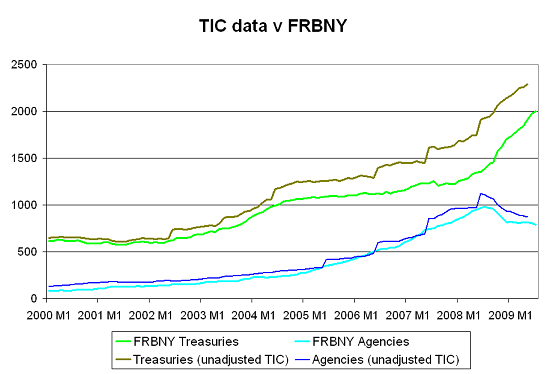

A quick chart showing how my estimates (from work I have done with Arpana Pandey of the CFR) for official holdings of Treasuries and Agencies compares with the FRBNY custodial holdings and the data that the US reports on the TIC website.

My estimates match those of the TIC in June of every year — when the data is revised. That is by design. All I am doing is using data on flows through the UK and Hong Kong to smooth out the revisions over the course of the year, and thus to avoid the sudden jumps in the official data.

This post is by Mark Dow

Very few things rouse the rabble as much as an ideological debate. And over the past year it has been looking like we are having the beginnings of a nasty one in economics and finance. The current economic and financial crisis has shaken a few trees and made many go back and question first principles. Often, the answer is that the prevailing received economic and financial wisdom has fallen woefully short.

That said, those who are looking for a debate here may be disappointed. A narrow ideological debate is not the can I wanted to open up. Instead, I thought it would be useful to review from an historical perspective how we got here, and then address why this should matter.

For me, making the transition from economist to trader raised a lot of issues about efficient markets and animal spirits. It underscored the shortcomings of formal training and our incomplete understanding of the human element in finance and economics. As a result, the issue of paradigm shift has been simmering on my backburner for quite some time now.

One of the most important lessons I have learned as a trader is not just that emotions play an outsized role in market dynamics—that much became clear quite quickly—but that the emotions regularly swing, as if they were a pendulum, from one local extreme to the opposite. In other words, around any given trend there are oscillations above and below, moments of high bullishness and high bearishness. Time and time again we transition from moments when any positive statement is met with skepticism to moments when no one dares say anything negative. In short, we slowly change directions, see that the new direction starts to work and jump on, take the new direction too far so that it stops working, and then we start the whole process all over again.

These pendular swings in the market can take anywhere from a couple of weeks to numerous months, and they are marked by a distinct, three part psychological process: denial, migration, capitulation. In the first phase, participants deny that a change in market character is truly afoot. Markets rally on bad news (or sell off on good news) and traders look for others to blame for their trading losses (suggestion: when in doubt blame government; no one will ever disagree.) Then, little by little, traders begin to recognize ‘what is working’, start to question their previous beliefs, and then begin migrating from their old camp to the new. In the last phase, capitulation (or give-up phase), the final holdouts switch camps and jump on the new bandwagon—often in climatic fashion. This then completes the pendular swing.

This manifestation of human nature is not confined to intermediate term swings in the market. It also applies to ideological fashions in economics. At the time of the Great Depression the prevailing ideology was the Austrian Business Cycle School, a variant of the classical school of economics. (This school of thought was responsible for the useful term “creative destruction”). As the Depression took hold, the policy response was to allow the system to purge itself of its excesses. In retrospect, the mainstream view is that this policy response—or lack thereof—severely exacerbated the length and depth of the downturn.

Economists of every stripe have their own pet reasons as to what caused the Great Depression and what got us out of it. Leaving this debate aside, it is not controversial to say that Keynesian polices were perceived to have helped lift the US out of the Depression.

One of the biggest economic and political stories of this decade has been China’s emergence as the world’s biggest creditor country. At least in a ‘flow” sense. China’s current account surplus is now the world’s largest – and its government easily tops a “reserve and sovereign wealth fund” growth league table. The growth in China’s foreign assets at the peak of the oil boom – back when oil was well above $100 a barrel – topped the growth in the foreign assets of all the oil-exporting governments. Things have tamed down a bit – but China still is adding more to its reserves than anyone else.

Yet China is in a lot of ways an unusual creditor, for three reasons:

One, China is still a very poor country. It isn’t obvious why it makes sense for China to be financing other countries’ development rather than its own. That I suspect is part of the reason why China’s government seems so concerned about the risk of losses on its foreign assets.

Two, almost all outflows from China come from China’s government. Private investors generally have wanted to move money into China at China’s current exchange rate. The large role of the state in managing China’s capital outflows differentiates China from many leading creditor countries, and especially the US and the UK. Of course, the US government organized large loans to help Europe reconstruct in the 1940s and early 1950s, and thus the US government played a key role recycling the United States current account surplus during this period. But later in the 1950s and in the 1960s, the capital outflows that offset the United States current account surplus (and reserve-related inflows) largely came from private US individuals and firms. And back in the nineteenth century, private British investors were the main financiers of places like Argentina, Australia and the United States. We now live in a market-based global financial system where the biggest single actor is a state.

Three, unlike many past creditors, China doesn’t lend to the world in its own currency. It rather lends in the currencies of the “borrowing” countries – whether the US dollar, the euro, the British pound or the Australian dollar. That too is a change from historical norms. Many creditor countries have wanted debtors to borrow in the currency of the creditor country. To be sure, that didn’t always work out: it makes outright default more likely (ask those who lent to Latin American countries back in the twentieth century … ). But it did offer creditors a measure of protection against depreciation of the debtor’s currency.

This system was basically stable for the past few years – though not with out its tensions. Now though there are growing voices calling for change.

This post is by Brad Setser and Rachel Ziemba of RGE Monitor

A score of recent reports have put the total assets managed by sovereign wealth funds at around $3 trillion. That seems high to us – at least if the estimate is limited to sovereign wealth funds external assets.

We don’t know the real total of course. Key institutions do not disclose their size – or enough information to allow definitive estimates of their size. But our latest tally would put the combined external assets of the major sovereign wealth funds roughly $1.5 trillion (as of June 2009) – rather less than many other estimates. This portfolio of $1.5 trillion does reflect an increase from the lows reached of late 2008. But it is well below the estimated $1.8 trillion in sovereign funds assets under management in mid 2008. Significant exposure to equities and alternative assets like property, hedge funds and private equity led to heavy losses by most funds in 2008 – a fact admitted by many of the managers.

$1.5 trillion is lot of money. But it is substantially less than $7 trillion or so held as traditional foreign exchange reserves.

There are three main reasons for our lower total.

First, we continue to believe that the foreign assets of Abu Dhabi’s two main sovereign funds – The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), and the smaller Abu Dhabi Investment Council (which was created out of ADIA and manages some of ADIA’s former assets) – are far smaller than many continue to claim.* Our latest estimate puts their total size at about $360 billion. That is roughly the same size as the $360 billion Norwegian government fund – and more than the estimated assets of the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) and the combined assets of Singapore’s GIC and Temasek. Our estimate for the GIC’s assets under management is also on the low side.

To be sure, Abu Dhabi’s total external assets exceed those managed by ADIA and the Abu Dhabi Investment Council. Abu Dhabi has another sovereign fund – Mubadala and a number of other government backed investors. Its mandate has long been to support Abu Dhabi’s internal development (“Mubadala [was] set up in 2002 with a mandate not only to seek a return on investment but also to attract businesses to Abu Dhabi and help diversify the emirate’s economy) but it now has a substantial external portfolio as well. Chalk up another $50 billion or so there. Sheik Mansour’s recent flurry of investments also has made it clear that not all of Abu Dhabi’s external wealth is managed by ADIA, the Council and Mubadala. The line between a sovereign wealth fund, a state company and the private investments of individual members of the ruling family isn’t always clear. Abu Dhabi as a whole likely has substantially more foreign assets than the $400 billion we estimate are held by ADIA, the Abu Dhabi Investment Council and Mubadala. And despite Dubai’s vulnerabilities, it still holds a good number of foreign assets, even if its highly leveraged portfolio has suffered greatly in the last year.

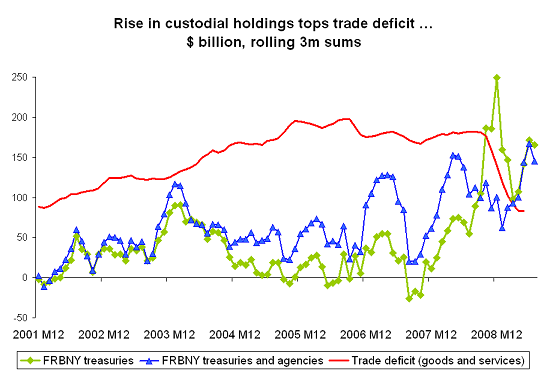

The Fed’s custodial holdings of Treasuries just topped $2 trillion. Custodial holdings of Treasuries rose by $25 billion in July. The overall pace of growth in the Fed’s custodial holdings did slow a bit in July, as some of the rise in Treasuries was offset by a fall in Agency holdings. But in a world where the US trade deficit is running at about $30 billion a month, a $15 billion monthly increase in the Fed’s custodial holdings is significant.

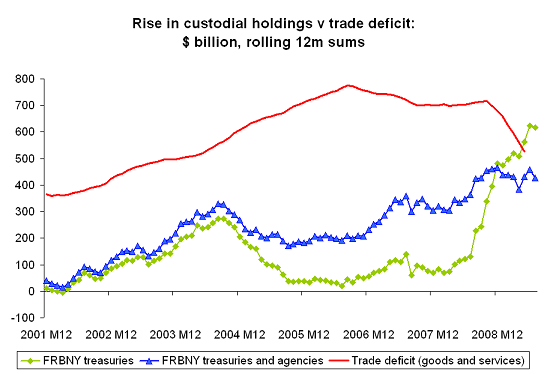

I understand why the Treasury market is so focused on Chinese demand — China is a the largest player in the market, and a major shift in Chinese demand would almost certainly have an impact. Right now, the market is obsessing over the low level of indirect bids in last week’s 2 year auction. At the same time, concern that central banks are abandoning Treasuries should be muted so long as the rise in the Fed’s custodial holdings of Treasuries is running far above the US trade deficit. Barring a huge increase in the trade deficit after May, that is certainly will be case over the last three months of data.

It is also true on a 12m basis.

The Fed’s custodial holdings may exaggerate central bank purchases a bit, as central banks sought safety in the crisis and moved funds out of private accounts. But so long as the custodial holdings of Treasuries are rising so rapidly, it is a little hard to argue that central bank reserve managers aren’t willing to hold dollars.

Qing Wang of Morgan Stanley: “Given China’s high national savings rate, from the perspective of the economy as a whole, there are only three forms in which China can deploy its savings: 1) onshore physical assets; 2) offshore physical assets; and 3) offshore financial assets. …. We therefore think that from the perspective of the economy as a whole, the opportunity cost of domestic fixed asset investment, or formation of physical assets onshore, should be the total returns on US government bonds. Put in simple terms, in the debate about over-investment at the current juncture, it actually boils down to an investment decision on building railways in China versus buying US government bonds, given China’s high national savings.

David Pilling: “Far from a sign of strength, Beijing’s accumulation of vast foreign reserves is the side-effect of an economic model too reliant on exports. The enormous trade surplus is the product of an undervalued renminbi that has allowed others to consume Chinese goods at the expense of Chinese people themselves. Beijing cannot dream of selling down its Treasury holdings without triggering the very dollar collapse it purports to dread. Nor are its shrill calls for the US to close its twin deficits – which would inevitably involve buying fewer Chinese goods – entirely convincing. Rather than exposing the superiority of China’s state-led model, the global financial crisis has laid bare the compromising embrace in which the US and China find themselves. ”

Peter Garnham touches on similar themes for the FT.

Philip Bowring on the obstacles (mostly self-created) to internationalizing the renminbi: “China’s expressions of desire to reduce the role of the dollar are anyway contradicted by its actual policy of maintaining a de facto peg to the U.S. currency, meanwhile continuing to accumulate dollars in reserves now totaling $2 trillion. The modest yuan appreciation after 2005 came to a halt more than a year ago as China has sought to sustain exports in the face of the global slump. There is conflict between macro-economic stabilization goals and pressures from industries and employment creation not to put more pressure on exporters. … Nor has there been any significant move towards full convertibility as the financial crisis has, with good reason, made the authorities nervous of liberalization …. any significant use of yuan requires and significant offshore stock of the currency. That is incompatible with China’s expressed desire to reduce its dollar reserve dependence.”

Robert Pozen on the limits of the SDR.

Michael Pettis on his blog and in the Financial Times: ” If the Chinese economy was the biggest beneficiary of excess US consumption growth, it is likely also to be the biggest victim of a rising US savings rate. … Eventually, and maybe this is already happening, the decline in the US trade deficit must result in a decline in China’s ability to export the difference between its growth in production and consumption. When this happens, China’s economy will grow more slowly than Chinese consumption, just as the opposite is happening in the US. Put another way, rather than act as the lower constraint for GDP growth as it has for the past two decades growth in Chinese consumption will become the upper constraint, as for the next several years Chinese consumption necessarily rises as a share of GDP, just as US consumption must decline as a share of US GDP.

This post is by Brad Setser and Paul Swartz of the Council on Foreign Relations.

No doubt today’s GDP release will attract the lion’s share of the econoblogosphere’s attention. But sometimes it is a good idea to counter-program.

Paul Swartz, I and others at the Council’s Center for Geoeconomic Studies have been – at the prodding of our boss – trying to come up with indicators that capture “Geoeconomic” risk. Or at least to develop measures some key “geoeconomic” concepts, with geoeconomics defined as anything that touches on both the economy and geopolitics. An example might be the gapminder chart we did for the Council’s multimedia spectacular on the financial crisis that touches on the question of whether the G-7 still brings together the world’s most economically powerful countries.

I am not sure that we have succeeded, though I do think we have come up with some interesting ideas – ideas, though, that need to be stress tested with a bit of external scrutiny. Call this a very rough working draft.

One idea has been to look at what share of the world’s total economic output is produced by democratic countries. To do this, we weighted output by a measure of a country’s political openness (from the Polity IV project). A low score implies that all of the world’s output is produced in countries that are not democracies. A high score means all the output is produced by countries that are well-functioning democracies. And a score in the middle means something in the middle – either there are a lot of economically large democracies and a lot of economically large autocracies, or that a lot of global output is produced by countries that aren’t total autocracies nor perfect democracies.

The results are interesting; the end of the Cold war increased the share of output produced by the world’s democracies. But China’s ability to grow rapidly with significantly democraticizing has made the global economy a bit less “democratic” (in the sense that less of the world’s output is produced by democracies).

That implies that if current economic trends – meaning the gap between the rate of growth between autocratic and more democratic countries — continue, the share of global output produced by democracies will decline over time.

It is now rather common to argue that those economists who anticipated the crisis anticipated the wrong crisis – a dollar crisis, not a banking crisis. Robin Harding of the FT writes:

“If economists try to predict crises they will get it wrong, and that will reduce their credibility when they try to warn of risks. It was in their warnings that economists failed: plenty talked of ‘global imbalances’ or ‘excessive credit growth’; few followed that through to the proximate sources of danger in the financial system, and then forcibly argued for something to be done about it.”

Free exchange made a similar point last week.

“It’s interesting that he [Krugman] mentions Nouriel Roubini, who is one of several international economists who famously saw some sort of crisis on the horizon but who very much erred in guessing the precipitating factor. I think international macroeconomists have been looking for a dollar crisis for quite some time, and they believed that such a crisis would bring on the meltdown. Instead, the meltdown occurred for other reasons and paradoxically reinforced the position of the dollar (and, for the moment, many of the structural imbalances that have troubled international economists).”

Actually, the crisis has — at least temporarily — reduced those structural imbalances. The US trade deficit is much smaller now than before. And, be honest, the criticism directed at Dr. Roubini should have been directed at me: after 2005, the locus of Nouriel’s concerns shifted to the housing market and the financial sector, while I continued to focus on the risks associated directly with the US external deficit. But it is hard to argue against the conclusion that the current crisis stems, fundamentally, from the collapse in the financial sector’s ability to intermediate the US household deficit – not a collapse in the rest of the world’s willingness to accumulate dollars. The chain of risk intermediation broke down in New York and London before it broke down in Beijing, Moscow or Riyadh.

At the same time, I also think the argument that warnings about “imbalances” (meaning the US trade deficit) were wrong neglects one important thing: there was something of a balance of payments crisis in 2007, although it took a very unusual form. When US growth slowed and global growth did not, private investors (limited) willingness to finance the US deficit disappeared. Consider the following graph, which plots (net) private demand for US long-term financial assets (it is based on the TIC data, but I have adjusted the TIC data for “hidden” official inflows that show up in the Treasury’s annual survey of foreign portfolio investment) against the US trade deficit.

My post on the G-20′s agenda can be found on the official Pittsburgh Summit blog.

This will be my last blog post, at least for the foreseeable future. I have accepted a new job, one…

A quick chart showing how my estimates (from work I have done with Arpana Pandey of the CFR) for official…

This post is by Mark Dow Very few things rouse the rabble as much as an ideological debate. And over…

Bad Behavior has blocked 5225 access attempts in the last 7 days.