The

Labour Party is a

centre-left democratic socialist party in the

United Kingdom. It surpassed the

Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under

Ramsay MacDonald in

1924 and

1929-1931. The party was in a

wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after which it formed a

majority government under

Clement Attlee. Labour was also in government from

1964 to 1970 under

Harold Wilson and from

1974 to 1979, first under Wilson and then

James Callaghan.

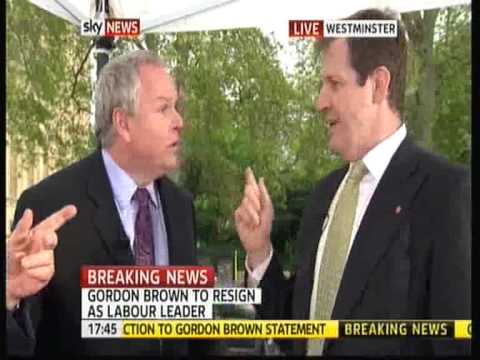

The Labour Party was last in government between 1997 and 2010 under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, beginning with a majority of 179, reduced to 167 in 2001 and 66 in 2005. Having won 258 seats in the 2010 general election, Labour is the Official Opposition. Labour has a working majority in the Welsh Assembly, is the main opposition party in the Scottish Parliament and has 13 members in the European Parliament. The Labour Party is a member of the Socialist International. The Party's current leader is Ed Miliband MP.

Party ideology

Throughout its history, the Labour Party has usually been thought of as being

left wing or

centre-left in its politics. Officially, it has maintained the stance of being a

socialist party ever since its inception, currently describing itself as a "

democratic socialist party". The party has been described as a

broad church, containing a diversity of ideological trends from strongly socialist, to more moderately social democratic, and in recent years pro-market tendencies. Throughout its history, it has been criticised by other leftist commentators and historians for not being truly socialist in its policies, instead supporting anti-socialist stances such as

capitalism and

neo-colonialism and has been described as a "capitalist workers' party".

Historically the party was broadly in favour of socialism, as set out in Clause Four of the original party constitution, and advocated socialist policies such as public ownership of key industries, government intervention in the economy, redistribution of wealth, increased rights for workers, the welfare state, publicly-funded healthcare and education. Beginning in the late-1980s continuing to the current day, the party has adopted free market policies, leading many observers to describe the Labour Party as Social Democratic or Third Way, rather than democratic socialist.

Party electoral manifestos have not contained the term ''socialism'' since 1992, when the original Clause Four was abolished. The new version states:

Party constitution and structure

The Labour Party is a membership organisation consisting of

Constituency Labour Parties,

affiliated trade unions,

socialist societies and the

Co-operative Party, with which it has an electoral agreement. Members who are elected to parliamentary positions take part in the

Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and European Parliamentary Labour Party (EPLP). The party's decision-making bodies on a national level formally include the

National Executive Committee (NEC),

Labour Party Conference and

National Policy Forum (NPF)—although in practice the Parliamentary leadership has the final say on policy. The 2008

Labour Party Conference was the first at which affiliated trade unions and Constituency Labour Parties did not have the right to submit motions on contemporary issues that would previously have been debated. Labour Party conferences now include more "keynote" addresses, guest speakers and question-and-answer sessions, while specific discussion of policy now takes place in the

National Policy Forum.

For many years Labour held to a policy of not allowing residents of Northern Ireland to apply for membership, instead supporting the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). The 2003 Labour Party Conference accepted legal advice that the party could not continue to prohibit residents of the province joining, and whilst the National Executive has established a regional constituency party it has not yet agreed to contest elections there.

The party had 198,026 members on 31 December 2005 according to accounts filed with the Electoral Commission, which was down on the previous year. In that year it had an income of about £35 million (£3.7 million from membership fees) and expenditure of about £50 million, high due to that year's general election.

As a party founded by the unions to represent the interests of working-class people, Labour's link with the unions has always been a defining characteristic of the party. In recent years this link has come under increasing strain, with the RMT being expelled from the party in 2004 for allowing its branches in Scotland to affiliate to the left-wing Scottish Socialist Party. Other unions have also faced calls from members to reduce financial support for the Party and seek more effective political representation for their views on privatisation, public spending cuts and the anti-trade union laws. Unison and GMB have both threatened to withdraw funding from constituency MPs and Dave Prentis of UNISON has warned that the union will write "no more blank cheques" and is dissatisfied with "feeding the hand that bites us".

International linkages

The party was a member of the

Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1940. It is currently, and since 1951, member of the

Socialist International, which was founded thanks to the efforts of the Clement Attlee leadership. Labour is also a member of the

Party of European Socialists, while the party's

MEPs sit in the

Socialists & Democrats group.

History

Founding of the party

The Labour Party's origins lie in the late 19th century, around which time it became apparent that there was a need for a new political party to represent the interests and needs of the urban proletariat, a demographic which had increased in number and had recently been given

franchise. Some members of the trades union movement became interested in moving into the political field, and after further extensions of the voting franchise in 1867 and 1885, the

Liberal Party endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time, with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the

Independent Labour Party, the intellectual and largely middle-class

Fabian Society, the

Social Democratic Federation and the

Scottish Labour Party.

In the 1895 general election, the Independent Labour Party put up 28 candidates but won only 44,325 votes. Keir Hardie, the leader of the party, believed that to obtain success in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to join with other left-wing groups. Hardie's roots as a Methodist lay preacher contributed to an ethos in the party which led to the comment by 1950s General Secretary Morgan Phillips that "Socialism in Britain owed more to Methodism than Marx".

Labour Representation Committee

In 1899, a Doncaster member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, Thomas R. Steels, proposed in his union branch that the Trade Union Congress call a special conference to bring together all left-wing organisations and form them into a single body that would sponsor Parliamentary candidates. The motion was passed at all stages by the TUC, and the proposed conference was held at the Memorial Hall on Farringdon Street on 26 and 27 February 1900. The meeting was attended by a broad spectrum of working-class and left-wing organisations — trades unions represented about one third of the membership of the TUC delegates.

After a debate, the 129 delegates passed Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." This created an association called the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), meant to coordinate attempts to support MPs sponsored by trade unions and represent the working-class population. It had no single leader, and in the absence of one, the Independent Labour Party nominee Ramsay MacDonald was elected as Secretary. He had the difficult task of keeping the various strands of opinions in the LRC united. The October 1900 "Khaki election" came too soon for the new party to campaign effectively; total expenses for the election only came to £33. Only 15 candidatures were sponsored, but two were successful; Keir Hardie in Merthyr Tydfil and Richard Bell in Derby.

Support for the LRC was boosted by the 1901 Taff Vale Case, a dispute between strikers and a railway company that ended with the union being ordered to pay £23,000 damages for a strike. The judgement effectively made strikes illegal since employers could recoup the cost of lost business from the unions. The apparent acquiescence of the Conservative Government of Arthur Balfour to industrial and business interests (traditionally the allies of the Liberal Party in opposition to the Conservative's landed interests) intensified support for the LRC against a government that appeared to have little concern for the industrial proletariat and its problems.

In the 1906 election, the LRC won 29 seats—helped by a secret 1903 pact between Ramsay MacDonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone that aimed to avoid splitting the opposition vote between Labour and Liberal candidates in the interest of removing the Conservatives from office.

In their first meeting after the election the group's Members of Parliament decided to adopt the name "The Labour Party" formally (15 February 1906). Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party (in effect, the Leader), although only by one vote over David Shackleton after several ballots. In the party's early years the Independent Labour Party (ILP) provided much of its activist base as the party did not have individual membership until 1918 but operated as a conglomerate of affiliated bodies. The Fabian Society provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party. One of the first acts of the new Liberal Government was to reverse the Taff Vale judgement.

Early years and the rise of the Labour Party

The

1910 election saw 42 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons, a significant victory since, a year before the election, the House of Lords had passed the

Osborne judgment ruling that Trades Unions in the United Kingdom could no longer donate money to fund the election campaigns and wages of Labour MPs. The governing Liberals were unwilling to repeal this judicial decision with primary legislation. The height of Liberal compromise was to introduce a wage for Members of Parliament to remove the need to involve the Trade Unions. By 1913, faced with the opposition of the largest Trades Unions, the Liberal government passed the Trade Disputes Act to allow Trade Unions to fund Labour MPs once more.

During the First World War the Labour Party split between supporters and opponents of the conflict but opposition to the war grew within the party as time went on. Ramsay MacDonald, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party and Arthur Henderson became the main figure of authority within the party. He was soon accepted into Prime Minister Asquith's war cabinet, becoming the first Labour Party member to serve in government.

Despite mainstream Labour Party's support for the coalition the Independent Labour Party was instrumental in opposing conscription through organisations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship while a Labour Party affiliate, the British Socialist Party, organised a number of unofficial strikes.

Arthur Henderson resigned from the Cabinet in 1917 amid calls for party unity to be replaced by George Barnes. The growth in Labour's local activist base and organisation was reflected in the elections following the war, the co-operative movement now providing its own resources to the Co-operative Party after the armistice. The Co-operative Party later reached an electoral agreement with the Labour Party. The Communist Party of Great Britain was refused affiliation between 1921 and 1923.

Meanwhile the Liberal Party declined rapidly and the party suffered a catastrophic split that allowed the Labour Party to co-opt much of the Liberals' support.

With the Liberals in disarray Labour won 142 seats in 1922, making it the second largest political group in the House of Commons and the official opposition to the Conservative government. After the election the now-rehabilitated Ramsay MacDonald was voted the first official leader of the Labour Party.

First Labour government (1924)

The

1923 general election was fought on the Conservatives'

protectionist proposals but, although they got the most votes and remained the largest party, they lost their majority in parliament, necessitating the formation of a government supporting

free trade. Thus, with the acquiescence of Asquith's Liberals,

Ramsay MacDonald became the first ever Labour Prime Minister in January 1924, forming the first Labour government, despite Labour only having 191 MPs (less than a third of the House of Commons).

Because the government had to rely on the support of the Liberals it was unable to get any legislation of an arguably socialist nature passed by the House of Commons. The most significant and long-lasting measure was the Wheatley Housing Act, which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rental to working-class families. Legislation on education, unemployment and social insurance were also passed.

The government collapsed after only nine months when the Liberals voted for a Select Committee inquiry into the Campbell Case, a vote which MacDonald had declared to be a vote of confidence. The ensuing general election saw the publication, four days before polling day, of the notorious Zinoviev letter, which implicated Labour in a plot for a Communist revolution in Britain. The Conservatives were returned to power although Labour increased its vote from 30.7% to a third of the popular vote, most Conservative gains being at the expense of the Liberals. The Zinoviev letter is now known to have been a forgery.

In opposition Ramsay MacDonald continued his policy of presenting the Labour Party as a moderate force. During the General Strike of 1926 he opposed strike action, arguing that the best way to achieve social reforms was through the ballot box.

Second Labour government (1929–1931)

In the

1929 general election, the Labour Party became the largest in the House of Commons for the first time, with 287 seats and 37.1% of the popular vote. However MacDonald was still reliant on Liberal support to form a minority government. MacDonald went on to appoint Britain's first female cabinet minister,

Margaret Bondfield, who was appointed

Minister of Labour.

The government, however, soon found itself engulfed in crisis: the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and eventual Great Depression occurred soon after the government came to power, and the crisis hit Britain hard. By the end of 1930 unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million. The government had no effective answers to the crisis. A sudden budgeting crisis in the summer of 1931 split the cabinet over whether the rate of unemployment benefit should be reduced; when it became clear that leading Ministers who were opposed would resign, the Government could no longer continue.

To the surprise of fellow Ministers, MacDonald returned from seeing the King having agreed to head a "National Government" with Conservative and Liberal Ministers. A small number of Labour ministers joined him, causing great anger among those within the Labour Party who felt betrayed by MacDonald's actions: he and his supporters were later expelled from the Labour Party. Arthur Henderson returned to the party leadership and repudiated all spending cuts. When the economic crisis did not abate, the National Government called a general election and won an overwhelming victory (MacDonald's supporters having formed a scratch National Labour group). The election was a disaster for the Labour Party which won only 46 seats, together with 3 for the Independent Labour Party and 3 Labour candidates who did not have official endorsement. The total of 52 was 225 fewer than in 1929.

In opposition during the 1930s

Arthur Henderson, elected in 1931 to succeed MacDonald, lost his seat in the

1931 general election. The only former Labour cabinet member who had retained his seat, the pacifist

George Lansbury, accordingly became party leader.

The party experienced another split in 1932 when the Independent Labour Party, which for some years had been increasingly at odds with the Labour leadership, opted to disaffiliate from the Labour Party and embarked on a long, drawn-out decline.

Lansbury resigned as leader in 1935 after public disagreements over foreign policy. He was promptly replaced as leader by his deputy, Clement Attlee, who would lead the party for two decades. The party experienced a revival in the 1935 general election, winning 154 seats and 38% of the popular vote, the highest that Labour had achieved.

As the threat from Nazi Germany increased in the 1930s the Labour Party gradually abandoned its earlier pacifist stance and supported re-armament, largely due to the efforts of Ernest Bevin and Hugh Dalton who by 1937 had also persuaded the party to oppose Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement.

A plan in Leeds to demolish and replace all the back-to-back houses by five-year stages was accepted by the council in 1933 under the inspiration of the Reverend Charles Jenkinson, a Labour Party member who became the leader of their council when Labour won control of it in 1933. Out of the 72,000 back-to-back houses in Leeds, 8,000 were replaced by 1935.

Wartime coalition (1940-1945)

The party returned to government in 1940 as part of the

wartime coalition. When

Neville Chamberlain resigned in the spring of 1940, incoming-

Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to bring the other main parties into a coalition similar to that of the First World War. Clement Attlee was appointed

Lord Privy Seal and a member of the war cabinet, eventually becoming the United Kingdom's first

Deputy Prime Minister.

A number of other senior Labour figures also took up senior positions; the trade union leader Ernest Bevin, as Minister of Labour, directed Britain's wartime economy and allocation of manpower, the veteran Labour statesman Herbert Morrison became Home Secretary, Hugh Dalton was Minister of Economic Warfare and later President of the Board of Trade, while A. V. Alexander resumed the role he had held in the previous Labour Government as First Lord of the Admiralty. According to G.D.H. Cole, the basis of the Wartime Coalition was that the labour ministers would look after the “Home Front” (including the maintenance of important social services and the mobilisation of manpower). Although the Exchequer remained in the hands of the Conservative Party, a firm understanding was made with Labour regarding the equitable distribution of tax burdens.

While serving in coalition with the Conservatives, the Labour members of Churchill's cabinet were able put their democratic socialist ideals into practice, implementing a wide range of progressive social and economic reforms which did much to improve the living standards and working conditions of working-class Britons. As observed by Kenneth O. Morgan, “Labour ministers were uniquely associated with the triumphs on the home front.” Herbert Morrison at the Home Office, assisted by his friend Ellen Wilkinson, was noted for his effective involvement in home defence and presiding over the repairs carried out on major cities affected by the Blitz. Arthur Greenwood, in his capacity as minister without portfolio, commissioned the Beveridge Report which would lay the foundations for the post-war British welfare state.

During the war years, the Labour Party was continuously active (with some success) in pushing for better arrangements of housing and billeting both of evacuees and of workers transferred for war services to already congested industrial areas, for fair systems of food rationing and distribution, for more effective control of prices, and for improvements in service pay and allowances. Labour also pressed hard for better provisions for the victims of air warfare, for more and better civic and industrial restaurants and canteens, and for war-time nurseries for the children of female workers.

In a manifesto on "The Peace," adopted by the 1941 Labour Party Annual Conference, it was claimed that Labour’s participation in the Wartime coalition Government had been effective in that, a year after Labour had joined the government, the war was now being fought not only with much greater efficiency, but with a higher regard for social equity as well:

“The area of the social services has been increased. Largely through the care and determination of the Trade unions, the standard of life has been well safeguarded. The health of the workers has been protected by the maintenance of the factory codes, and by the institution of factory doctors, canteens, and nurseries. Labour, national and local, has taken its share in civil defence; and in every sphere its activities have done much to improve the provision for the safety and comfort of citizens. The social protection of our people has been facilitated by the alert and continuous watch which has been kept over financial policy. Interest rates have been kept down. The Treasury has assumed powers over the Banks which assure their full co-operation in the policy upon which Parliament decides. The dangers of inflation, ever present in war-time, have been kept to a minimum.”

According to the historian G.D.H. Cole, Labour’s claims were arguably justified: profiteering was kept down, and there was greater equity both in the allocation of supplies and in taxation. In addition, social services were not merely kept up, but also expanded to meet wartime needs.

Tom Johnston used his position as Secretary of State for Scotland to push through a range of important developmental initiatives, such as the development of hydroelectricity in the Highlands, while Hugh Dalton’s regional policies directly assisted some of the Labour Party’s strongest cores of support. The Distribution of Industry Act 1945, pushed through by Hugh Dalton before the end of the wartime coalition, launched a vigorous policy of regenerating “depressed areas” such as industrial Scotland, the North-East of England, Cumbria, and South Wales, while diversifying the economic base of these regions. This foundation of this vigorous regional policy were actually laid during the Second World War, with the extension of the role of the trading estates and the linking of the industrial base of areas like the Welsh mining areas with the operations of government ordinance and armaments plants.

Co-operators, in common with the trade unions and labour, pressed hard from the outset of the war for the extension of the food rationing system to cover all essential supplies, arguing that the existence of an unrationed “sector” would create class injustices and result in time wasted on seeking supplies from shop to shop. Labour responded to Co-operative demands on these issues in March 1941 by establishing a Food Deputation Committee to work for more effective control and rationing of food supplies, together with the creation of an effective Consumers’ Council.

As Minister of Labour, Ernest Bevin did much to improve working conditions, raising the wages of the lowest paid male workers, such as miners, railwaymen, and agricultural labourers, while also persuading and forcing employers, under threat of removal of their Essential Works Order, to improve company medical and welfare provision, together with sanitary and safety provisions. This was important both for improving working conditions and for cementing worker consent to the war effort, and as a result of Bevin’s efforts, doctors, nurses, and welfare officers multiplied on the shop floor while there was a threefold increase in the provision of works canteens. Almost 5,000 canteens were directly created by Bevin in controlled establishments, while a further 6,800 were set up by private employers by 1944. During the course of the war, the number of works doctors increased from 60 to about 1,000. This provision, however, was much more extensive within larger factories, with smaller employers continuing “to barely comply with the minimum provision of a first aid box.” Accident rates did, however, decline after 1942.

The Second World War also saw significant improvements in the position of trade unions, which were encouraged by Bevin. Trade unions were integrated into joint consultation at all levels of government and industry, with the TUC drawn in to represent labour on the National Joint Advisory Council (1939) and the joint Consultative Committee (1940). A similar status was bestowed upon employers’ organisations, which led Middlemass to argue that capital and organised labour had become “governing institutions” within a tripartite industrial relations system “with the state at the fulcrum.” The elevation of the status of organised labour to one of parity with capital in Whitehall was effectively summed up by Bevin’s biographer as such:

“The organised working class represented by the trade unions was for the first time brought into a position of partnership in the national enterprise of war – a partnership on equal not inferior terms, as in the First World War.”

Collective bargaining was further extended by Bevin, who radically extended both the Wages Boards (the renamed Trades Boards) and the Whitley Committees, 46 of the latter were formed during the Second World War, and by the end of the war 15.5 million workers were covered by the minimum wage provisions by the Wages Boards. On the shop floor, Bevin directly encouraged the formation of joint production committees to extend worker’s participation in industry. By June 1944, almost 4,500 such committees were in existence, covering 3.5 million workers. By the end of the war, the joint production committees were intervening in areas once considered to be the sacrosanct domain of employers, such as health, welfare, transfers of labour, machine staffing, technology, piece rate fixing, and wage payment systems. These developments brought about significant improvements to conditions in the workplace, with a Mass Observation survey carried out in 1942 noting that “the quick sack and the unexplained instability” of the 1930s had practically vanished. During the 1940s, significant improvements in occupational health and safety standards were brought about both by the rising bargaining power of workers within the older “staple” sectors of the economy and the rise of “the pro-active wartime and post-war state.”

Also in the 1940s, trade union power and authority was extended further than in British history up until that point, with labour’s ability to regulate and control work significantly enhanced during this period. This was assisted by developments such as full employment, the growth of union membership, rising from 32% to 45% of the workforce from 1939 to 1950 and increasing workplace representation, as characterised by the large increase in the number of shop stewards. The progressive social changes were continued in the initial post-war period, with the creation of the Welfare State (which placed a floor under wages) and the extension of the legal rights of unions through the repeal of the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act (1927) in 1946, while the 1948 Industrial Injuries Act provided compensation for accidents in the workplace.

The war years also witnessed a significant extension of collective bargaining, which was directly encouraged by Bevin. By 1950, between nine and ten million workers were covered by collective voluntary bargaining. Bevin also established 46 new Joint Industrial Councils and extended the coverage of the Wages Boards between 1943 and 1945. By 1950, as a result of these changes, virtually all of the poorly organised and low-paid categories of workers were subject to state sponsored wage regulation and collective bargaining. This transformation in worker’s protection and bargaining power had the definitive effect of reducing long-established local and regional wage differences.

Bevin was also responsible for the passage of the Determination of Needs Act in 1941, which finally abolished the long-detested household means test. After the passage of the Determination of Needs Act, the Labour Movement continued to press for improvements, particularly for the extension of the principles of the new legislation to cover Public Assistance and other services as well (at that time, it only covered the Assistance Board). In 1943, this was achieved by further legislation, which also improved conditions relating to supplementary pensions. Throughout the war period, the Labour movement (both in and out of Parliament) pressed successfully for a number of changes liberalising the administration of the socials services.

The Catering Wages Act (1943), another initiative by Bevin, established a Catering Wages Commission to oversee wages and working conditions in restaurants and hotels. Inspectors were also appointed to ensure that employers complied with Bevin’s insistence on the provision of canteens, welfare officers, and personnel officers in factories. Bevin also did much to improve conditions for those with disabilities, of which little had been done for before the outbreak of the war. In 1941, Bevin introduced an interim retraining scheme, which was followed by the interdepartmental Tomlinson Committee of the Rehabilitation and Resettlement of the Disabled. According to the historian Pat Thane, the Committee served as “a mouthpiece for Bevin’s own aspirations,” and its proposals for improving the lives of the disabled culminated in the Disabled Persons Employment Act of 1944.

Bevin and the other Labour ministers were also able to ensure that, compared with the First World War, there was greater equality of sacrifice within society. Profiteering was effectively controlled, while rent controls and food subsidies helped to keep down wartime inflation. Wartime wages were allowed to increase in line with, and earnings to surpass, the rate of price inflation, while the tax system became more progressive, with taxation becoming heavier on the very rich (this movement towards greater progressivity was maintained under the Attlee government, with the top rate of income tax reaching 98% in 1949). These policies led to a narrowing of wealth inequalities, with the real value of wage incomes increasing by some 18% between 1938 and 1947, while the real value of property income fell by 15% and salaries by some 21% over that same period.

Post-war victory under Attlee

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, Labour resolved not to repeat the Liberals' error of 1918 but promptly withdrew from government to contest the

1945 general election in opposition to Churchill's Conservatives. Surprising many observers, Labour won a formidable victory, winning just under 50% of the vote with a majority of 145 seats.

Clement Attlee's proved one of the most radical British governments of the 20th century, presiding over a policy of nationalising major industries and utilities including the Bank of England, coal mining, the steel industry, electricity, gas, telephones and inland transport including railways, road haulage and canals. It developed and implemented the "cradle to grave" welfare state conceived by the economist William Beveridge. To this day the party considers the 1948 creation of Britain's publicly funded National Health Service under health minister Aneurin Bevan its proudest achievement. Attlee's government also began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) the following year. At a secret meeting in January 1947, Attlee and six cabinet ministers, including Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear weapons programme, in opposition to the pacifist and anti-nuclear stances of a large element inside the Labour Party.

Labour went on to win the 1950 general election but with a much reduced majority of five seats. Soon afterwards defence became a divisive issues within the party, especially defence spending (which reached a peak of 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War), straining public finances and forcing savings elsewhere. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, prompting Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (then President of the Board of Trade), to resign over the dilution of the principle of free treatment on which the NHS had been established.

In the 1951 general election, Labour narrowly lost to the Conservatives despite receiving the larger share of the popular vote, its highest ever vote numerically. Most of the changes introduced by the 1945–51 Labour government were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post war consensus" that lasted until the late 1970s.

Opposition during the 1950s

Following the defeat of 1951 the party underwent a long period of thirteen years in opposition. The party suffered an ideological split during the 1950s while the postwar economic recovery, given the social effects of Attlee's reforms, made the public broadly content with the Conservative governments of the time. Attlee remained as leader until his retirement in 1955.

His replacement Hugh Gaitskell, a man associated with the right-wing of the party, struggled to deal with internal divisions in the late 1950s and early 1960s and Labour lost the 1959 general election. In 1963 Gaitskell's sudden death from a heart-attack made way for Harold Wilson to lead the party.

Labour in government under Wilson (1964–1970)

A down-turn in the economy along with a series of scandals in the early 1960s (the most notorious being the

Profumo affair) engulfed the Conservative government by 1963. The Labour Party returned to government with a four-seat majority under Wilson in the

1964 election but increased its majority to 96 in the

1966 election.

Wilson's government was responsible for a number of sweeping social and educational reforms such as the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality (initially only for men aged 21 or over) and a significant expansion of the welfare state. In addition, comprehensive education was expanded and the Open University was created. As noted by one historian, in summing up the reform record of Wilson's government,

"In spite of the economic problems encountered by the First Wilson Government and in spite of (and to some degree in response to) the criticisms of its own supporters, Labour presided over a notable expansion of state welfare during its time in office."

Wilson's government had inherited a large trade deficit that led to a currency crisis and an ultimately doomed attempt to stave off devaluation of the pound. Labour went on to lose the 1970 election to the Conservatives under Edward Heath.

In opposition (1970-1974)

After losing the 1970 general election, Labour returned to opposition, but retained Harold Wilson as Leader. Heath's government soon ran into trouble over

Northern Ireland and a dispute with miners in 1973 which led to the "

three-day week". The 1970s were a difficult time to be in government for both the Conservatives and Labour due to the

1973 oil crisis which caused high inflation and a global recession. The Labour Party was returned to power again under Wilson a few weeks after the

February 1974 general election, forming a minority government with the support of the

Ulster Unionists. The Conservatives were unable to form a government as they had fewer seats despite receiving more votes numerically. It was the first general election since 1924 in which both main parties had received less than 40% of the popular vote and the first of six successive general elections in which Labour failed to reach 40% of the popular vote. In a bid to gain a proper majority, a second election was soon called for

October 1974 in which Labour, still with Harold Wilson as leader, managed a majority of three, gaining just 18 seats and taking its total to 319.

Return to government (1974-1979)

For much of its time in office the Labour government struggled with serious economic problems and a precarious majority in the Commons, while the party's internal dissent over Britain's membership of the

European Economic Community (EEC), which Britain had entered under Edward Heath in 1972, led in 1975 to a

national referendum on the issue in which two thirds of the public supported continued membership.

Harold Wilson's personal popularity remained reasonably high but he unexpectedly resigned as Prime Minister in 1976, citing health reasons and was replaced by James Callaghan. The Wilson and Callaghan governments of the 1970s tried to control inflation (which reached 23.7% in 1975) by a policy of wage restraint. This was fairly successful, reducing inflation to 7.4% by 1978, but led to increasingly strained relations between the government and the trade unions. The Labour governments of the 1970s did, however, manage to protect many people from the economic storm, with pensions increasing by 20% in real terms between 1974 and 1979, while measures such as rent controls and food and transport subsidies prevented the incomes of other people from deteriorating further.

Legislation was introduced which guaranteed annual uprating of benefits in line with increases in prices or average earnings, whichever was the highest. In addition, new benefits for the disabled and infirm were introduced whilst pensioners benefited from the largest ever increase in pensions up until that period. New employment legislation strengthened equal pay provisions, guaranteed payments for workers on short-time and temporarily laid-off and introduced job security and maternity leave for pregnant women.

A more effective system of workplace inspection was set up, together with the Health and Safety Executive, in response to the plight of many workers who suffered accidents or ill-health as a result of poor working conditions (whose plight which had long been ignored by the media). Industrial tribunals also provided protection through compensation for unfair dismissal, while the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service performed an effective function in the management of industrial disputes.

Although the Wilson and Callaghan governments were accused by many socialists of failing to put the Labour Party's socialist ideals into practice, it did much to bring about a greater deal of social justice in British society, as characterised by a significant reduction in poverty during the course of the 1970s, and arguably played as much as a role as the Attlee Government in advancing the cause of social democracy and reducing social and economic inequalities in the United Kingdom. As noted by one historian,

“In the seventeen years that it occupied office, Labour accomplished much in alleviating poverty and misery, and in giving help and sustenance to groups – the old, the sick, the disabled – least capable of protecting themselves in a market economy.”

Fear of advances by the nationalist parties, particularly in Scotland, led to the suppression of a report from Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone that suggested that an independent Scotland would be 'chronically in surplus'. By 1977 by-election losses and defections to the breakaway Scottish Labour Party left Callaghan heading a minority government, forced to trade with smaller parties in order to govern. An arrangement negotiated in 1977 with Liberal leader David Steel, known as the Lib-Lab Pact, ended after one year. After this deals were forged with various small parties including the Scottish National Party and the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru, prolonging the life of the government slightly.

The nationalist parties, in turn, demanded devolution to their respective constituent countries in return for their supporting the government. When referenda for Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979 Welsh devolution was rejected outright while the Scottish referendum returned a narrow majority in favour without reaching the required threshold of 40% support. When the Labour government duly refused to push ahead with setting up the proposed Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government: this finally brought the government down as it triggered a vote of confidence in Callaghan's government that was lost by a single vote on 28 March 1979, necessitating a general election.

Callaghan had been widely expected to call a general election in the autumn of 1978 when most opinion polls showed Labour to have a narrow lead. However he decided to extend his wage restraint policy for another year hoping that the economy would be in a better shape for a 1979 election. But during the winter of 1978-79 there were widespread strikes among lorry drivers, railway workers, car workers and local government and hospital workers in favour of higher pay-rises that caused significant disruption to everyday life. These events came to be dubbed the "Winter of Discontent".

In the 1979 election Labour suffered electoral defeat by the Conservatives, now led by Margaret Thatcher. The number of people voting Labour hardly changed between February 1974 and 1979 but in 1979 the Conservative Party achieved big increases in support in the Midlands and South of England, benefiting from both a surge in turnout and votes lost by the ailing Liberals.

The "Wilderness Years" (1979–1997)

After its defeat in the 1979 election the Labour Party underwent a period of internal rivalry between the left-wing, represented by

Michael Foot and

Tony Benn, and the right-wing represented by

Denis Healey. The election of Michael Foot as leader in 1980 led in 1981 to four former cabinet ministers from the right of the Labour Party (

Shirley Williams,

William Rodgers,

Roy Jenkins and

David Owen) forming the

Social Democratic Party.

The Labour Party was defeated heavily in the 1983 general election, winning only 27.6% of the vote, its lowest share since 1918, and receiving only half a million votes more than the SDP-Liberal Alliance who leader Michael Foot condemned for "siphoning" Labour support and enabling the Conservatives to win more seats.

Michael Foot resigned and was replaced as leader by Neil Kinnock who was elected on 2 October 1983 and progressively moved the party towards the centre. Labour improved its performance in 1987, gaining 20 seats and so reducing the Conservative majority from 143 to 102. They were now firmly established as the second political party in Britain as the Alliance had once again failed to make a breakthrough with seats and it subsequently collapsed, prompting a merger of the SDP and Liberals to form the Liberal Democrats.

Following the 1987 election, Kinnock began expelling Militant Tendency members from the party. They would later form the Socialist Party of England and Wales and the Scottish Socialist Party although a remnant of Militant continues to operate within the Labour Party through the newspaper ''Socialist Appeal''.

During the course of the 1980s, the GLC and several other Labour councils attempted to promote local economic recovery by setting up a network of enterprise boards and agencies. In addition, the GLC, Glasgow, Liverpool, Sheffield, and smaller London councils like Lambeth, Camden, and Islington adopted policies that challenged the Thatcher Government’s insistence on budgetary cuts and privatisation.

The Labour councils in old metropolitan counties of West Midlands, South Yorkshire, Greater London, and Greater Manchester led the way in developing interventionist economic policies. In the met county areas, Inward Investment Agencies, Enterprise Boards, Low Pay Units, and Co-operative Development Agencies proliferated, while parts of the country such as Salford Quays and Cardiff Bay were redeveloped. The Labour council in Birmingham in the 1980s worked to diversify the business visitor economy, as characterised by the decision to build a new, purpose-built convention centre in a decaying, inner-city district around Broad Street. By the mid-1990s, the success of this strategy was evident by the success of the International convention centre leading to wider redevelopment, as characterised by the building of a Sea Life Centre, the National Indoor Arena, bars, hotels, and thousands of newly constructed and refurbished flats and houses. This helped to revitalise the city centre and brought in people and money to both and the city and the West Midlands region as a whole.

In November 1990, Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister and was succeeded by John Major. Most opinion polls had shown Labour comfortably ahead of the Tories for more than a year before Mrs Thatcher's resignation, with the fall in Tory support blamed largely on the introduction of the unpopular poll tax, combined with the fact that the economy was sliding into recession at the time. One of the reasons Mrs Thatcher gave for her resignation was that she felt the Tories would stand a better chance of re-election with a new leader at the helm.

The change of leader in the Tory government saw a turnaround in support for the Tories, who regularly topped the opinion polls throughout 1991 although Labour regained the lead more than once.

The "yo yo" in the opinion polls continued into 1992, though after November 1990 any Labour lead in the polls was rarely sufficient for a majority. Major resisted Kinnock's calls for a general election throughout 1991. Kinnock campaigned on the theme "It's Time for a Change", urging voters to elect a new government after more than a decade of unbroken Conservative rule. However, the Conservatives themselves had undergone a dramatic change in the change of leader from Margaret Thatcher to John Major, at least in terms of style if not substance, whereas Kinnock was now the longest serving leader of any of the major political parties at the time and was now the longest-serving opposition leader in British political history.

From the outset, it was clearly a well-received change, as Labour's 14-point lead in the November 1990 "Poll of Polls" was replaced by an 8% Tory lead a month later.

The election on 9 April 1992 was widely tipped to result in a hung parliament or a narrow Labour majority, but in the event the Conservatives were returned to power, though with a much reduced majority of 21 in 1992. Despite the increased number of seats and votes, it was still an incredibly disappointing result for members and supporters of the Labour party, and for the first time in over 30 years there was serious doubt among the public and the media as to whether Labour could ever return to government.

Even before the country went to the polls, it seemed doubtful as to whether Labour could form a majority as an 8% electoral swing was needed across the country for this to be achieved.

Kinnock then resigned as leader and was replaced by John Smith.

The Black Wednesday economic disaster in September 1992 left the Conservative government's reputation for monetary excellence in tatters, and by the end of that year Labour had a comfortable lead over the Tories in the opinion polls. Although the recession was declared over in April 1993 and a period of strong and sustained economic growth followed, coupled with a relatively swift fall in unemployment, the Labour lead in the opinion polls remained strong.

However, Smith died from a heart attack in May 1994.

==="New Labour" – in government (1997–2010)===

Tony Blair continued to move the party further to the centre, abandoning the largely symbolic Clause Four at the 1995 mini-conference in a strategy to increase the party's appeal to "middle England". More than a simple re-branding, however, the project would draw upon a new political third way, particularly informed by the thought of the British sociologist Anthony Giddens.

"New Labour" was first termed as an alternative branding for the Labour Party, dating from a conference slogan first used by the Labour Party in 1994, which was later seen in a draft manifesto published by the party in 1996, called ''New Labour, New Life For Britain''. It was a continuation of the trend that had begun under the leadership of Neil Kinnock. "New Labour" as a name has no official status, but remains in common use to distinguish modernisers from those holding to more traditional positions, normally referred to as "Old Labour".

'New Labour is a party of ideas and ideals but not of outdated ideology. What counts is what works. The objectives are radical. The means will be modern.'

The Labour Party won the 1997 general election with a landslide majority of 179; it was the largest Labour majority ever, and the largest swing to a political party achieved since 1945. Over the next decade, a wide range of progressive social reforms were enacted, with millions lifted out of poverty during Labour's time in office largely as a result of various tax and benefit reforms.

Among the early acts of Tony Blair's government were the establishment of the national minimum wage, the devolution of power to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and the re-creation of a city-wide government body for London, the Greater London Authority, with its own elected-Mayor. Combined with a Conservative opposition that had yet to organise effectively under William Hague, and the continuing popularity of Blair, Labour went on to win the 2001 election with a similar majority, dubbed the "quiet landslide" by the media.

A perceived turning point was when Tony Blair controversially allied himself with US President George W. Bush in supporting the Iraq War, which caused him to lose much of his political support. The UN Secretary-General, among many, considered the war illegal. The Iraq War was deeply unpopular in most western countries, with Western governments divided in their support and under pressure from worldwide popular protests. At the 2005 election, Labour was re-elected for a third term, but with a reduced majority of 66. The decisions that led up to the Iraq war and its subsequent conduct are currently the subject of Sir John Chilcot's Iraq Inquiry.

Tony Blair announced in September 2006 that he would quit as leader within the year, though he had been under pressure to quit earlier than May 2007 in order to get a new leader in place before the May elections which were expected to be disastrous for Labour. In the event, the party did lose power in Scotland to a minority Scottish National Party government at the 2007 elections and, shortly after this, Tony Blair resigned as Prime Minister and was replaced by his Chancellor, Gordon Brown. Although the party experienced a brief rise in the polls after this, its popularity soon slumped to its lowest level since the days of Michael Foot. During May 2008, Labour suffered heavy defeats in the London mayoral election, local elections and the loss in the Crewe and Nantwich by-election, culminating in the party registering its worst ever opinion poll result since records began in 1943, of 23%, with many citing Brown's leadership as a key factor.

Finance proved a major problem for the Labour Party during this period; a "cash for peerages" scandal under Tony Blair resulted in the drying up of many major sources of donations. Declining party membership, partially due to the reduction of activists' influence upon policy-making under the reforms of Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair, also contributed to financial problems. Between January and March 2008, the Labour Party received just over £3 million in donations and were £17 million in debt; compared to the Conservatives' £6 million in donations and £12 million in debt.

In the 2010 general election on 6 May that year, Labour with 29.0% of the vote won the second largest number of seats (258). The Conservatives with 36.5% of the vote won the largest number of seats (307), but no party had an overall majority, meaning that Labour could still remain in power if they managed to form a coalition with at least one smaller party. However, the Labour Party would have had to form a coalition with more than one other smaller party to gain an overall majority; anything less would result in a minority government. On 10 May 2010, after talks to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats broke down, Gordon Brown announced his intention to stand down as Leader before the Labour Party Conference but a day later resigned as both Prime Minister and party leader.

In opposition (2010–present)

Harriet Harman became the

Leader of the Opposition and acting Leader of the Labour Party following the resignation of Gordon Brown on 11 May 2010, pending a

leadership election subsequently won by

Ed Miliband. This period has to date witnessed a revival in Labour's opinion poll fortunes, with the first Labour lead recorded since the commencement of Gordon Brown's premiership in 2007 being reported in a

YouGov poll for

The Sun on 27 September 2010 during the

2010 Labour Party Conference. This phenomenon has been speculatively attributed to the

sharp decline in

Liberal Democrat support since May 2010, with disillusioned Liberal Democrat supporters defecting their support to Labour. Such poll leads, up to 6% above the

Conservatives in a 20 December 2010 opinion poll, are in contrast to Ed Miliband's low public satisfaction ratings; +1% in an

Ipsos MORI poll, interpreted by a spokesperson for the said pollster as "...bad news for Ed Miliband. We have to go back to Michael Foot who led the party to a crushing defeat in 1983 to find a lower satisfaction rating at this stage".Foot, in fact, had actually enjoyed a lead in the opinion polls over the Tories wide enough to win an election with a majority of up to 130 seats immediately after becoming leader in 1980,although that lead was wiped out in 1981 following the advent of the

Social Democratic Party.

The new leadership of the party has been seeking a coherent ideological position to answer Cameron's 'Big Society' rhetoric, and also mark a seachange from the neoliberal ideology of Blair and 'New Labour'. Blue Labour is a recent, and had been increasingly influential ideological tendency in the party that advocates the belief that working class voters will be won back to Labour through more conservative policies on certain social and international issues, such as immigration and crime, a rejection of neoliberal economics in favour of ideas from guild socialism and continental corporatism, and a switch to local and democratic community management and provision of services, rather than relying on a traditional welfare state that is seen as excessively 'bureaucratic'. These ideas have been given an endorsement by Ed Miliband who in 2011 wrote the preface to a book expounding Blue Labour's positions However, it lost influlence after comments by Maurice Glasman in the Telegraph newspaper.

Electoral performance

†The first election held under the Representation of the People Act 1918 in which all men over 21, and most women over the age of 30 could vote, and therefore a much larger electorate

‡The first election under universal suffrage in which all women aged over 21 could vote

==Leaders of the Labour Party since 1906==

Keir Hardie, 1906–1908

Arthur Henderson, 1908–1910

George Nicoll Barnes, 1910–1911

Ramsay MacDonald, 1911–1914

Arthur Henderson, 1914–1917

William Adamson, 1917–1921

John Robert Clynes, 1921–1922

Ramsay MacDonald, 1922–1931

Arthur Henderson, 1931–1932

George Lansbury, 1932–1935

Clement Attlee, 1935–1955

Hugh Gaitskell, 1955–1963

George Brown, 1963 †

Harold Wilson, 1963–1976

James Callaghan, 1976–1980

Michael Foot, 1980–1983

Neil Kinnock, 1983–1992

John Smith, 1992–1994

Margaret Beckett, 1994 †

Tony Blair, 1994–2007

Gordon Brown, 2007–2010

Harriet Harman, 2010 †

Ed Miliband, 2010–present

†Although these were technically leaders of the Labour Party, they only assumed this role because of the death or resignation of the incumbent and were not elected to the post. They were in effect acting temporary leaders. Margaret Beckett was deputy leader when leader John Smith unexpectedly died, and she automatically became leader as a result of his death. Similarly, George Brown, who became leader after the death of Hugh Gaitskell, had been deputy leader at the time of Gaitskell's death. Harriet Harman was deputy leader when Gordon Brown resigned the leadership in the wake of his May 2010 election defeat, and she too became leader automatically and remained leader while the Labour Party went through the process of electing a new leader.

Deputy Leaders of the Labour Party since 1922

John Robert Clynes, 1922–1932

William Graham, 1931–1932

Clement Attlee, 1932–1935

Arthur Greenwood, 1935–1945

Herbert Morrison, 1945–1955

Jim Griffiths, 1955–1959

Aneurin Bevan, 1959–1960

George Brown, 1960–1970

Roy Jenkins, 1970–1972

Edward Short, 1972–1976

Michael Foot, 1976–1980

Denis Healey, 1980–1983

Roy Hattersley, 1983–1992

Margaret Beckett, 1992–1994

John Prescott, 1994–2007

Harriet Harman, 2007–present

Leaders of the Labour Party in the House of Lords since 1924

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, 1924–1928

Charles Cripps, 1st Baron Parmoor, 1928–1931

Arthur Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede, 1931–1935

Harry Snell, 1st Baron Snell, 1935–1940

Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison, 1940–1952

William Jowitt, 1st Earl Jowitt, 1952–1955

Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough, 1955–1964

Frank Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford, 1964–1968

Edward Shackleton, Baron Shackleton, 1968–1974

Malcolm Shepherd, 2nd Baron Shepherd, 1974–1976

Fred Peart, Baron Peart, 1976–1982

Cledwyn Hughes, Baron Cledwyn of Penrhos, 1982–1992

Ivor Richard, Baron Richard, 1992–1998

Margaret Jay, Baroness Jay of Paddington, 1998–2001

Gareth Williams, Baron Williams of Mostyn, 2001–2003

Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos, 2003–2007

Catherine Ashton, Baroness Ashton of Upholland, 2007–2008

Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, 2008–present

Labour Prime Ministers

See also

{|width=100%

|- valign=top

|width=33%|

Labour Co-operative

History of British Socialism

Labour leadership election

List of organisations associated with the British Labour Party

List of Labour Party (UK) MPs

List of other Labour Parties

Politics of the UK

Young Labour

|width=33%|

Welsh Labour

Scottish Labour Party

Blue Labour

Liberal Democrats

Conservative Party

Socialist Party (England and Wales)

Socialist Labour Party (UK)

Labour Students

List of UK Labour Party general election manifestos

|}

References

Further reading

Davies, A.J, ''To Build A New Jerusalem'' (1996) ISBN

Stephen Driver and Luke Martell, ''New Labour: Politics after Thatcherism'', Polity Press, 1998 and 2006

Geoffrey Foote, ''The Labour Party's Political Thought: A History'', Macmillan, 1997 ed.

Martin Francis, ''Ideas and Policies under Labour 1945–51'', Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN

Roy Hattersley, ''New Statesman'', 10 May 2004, 'We should have made it clear that we too were modernisers'

David Howell, ''British Social Democracy'', Croom Helm, 1976

David Howell, ''MacDonald's Party'', Oxford University Press, 2002

H. C. G. Matthew, R. I. McKibbin, J. A. Kay. "The Franchise Factor in the Rise of the Labour Party," ''English Historical review'' Vol. 91, No. 361 (Oct., 1976) , pp. 723–752 in JSTOR

Ralph Miliband, ''Parliamentary Socialism'', Merlin, 1960, 1972, ISBN

Kenneth O. Morgan, ''Labour in Power, 1945-51'', OUP, 1984

Kenneth O. Morgan, ''Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants, Hardie to Kinnock'' OUP, 1992, ISBN

Henry Pelling and Alastair J. Reid, ''A Short History of the Labour Party'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2005 ed. ISBN

Ben Pimlott, ''Labour and the Left in the 1930s'', Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Raymond Plant, Matt Beech and Kevin Hickson (2004), ''The Struggle for Labour's Soul: understanding Labour's political thought since 1945'', Routledge, ISBN

Clive Ponting, ''Breach of Promise, 1964-70'', Penguin, 1990, ISBN

Greg Rosen, ''Dictionary of Labour Biography''. Politicos Publishing, 2001, ISBN

Greg Rosen, ''Old Labour to New'', Politicos Publishing, 2005, ISBN

Eric Shaw, ''The Labour Party since 1979: Crisis and Transformation'', Routledge, 1994

Andrew Thorpe, ''A History of the British Labour Party'', Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, ISBN

Phillip Whitehead, ''The Writing on the Wall'', Michael Joseph, 1985

Patrick Wintour and Colin Hughes, ''Labour Rebuilt'', Fourth Estate, 1990

John Pilger, Freedom Next Time, Bantam Press, 2006, ISBN

External links

Official party sites

Labour

Scottish Labour

Welsh Labour

London Assembly Labour

Young Labour - Party youth wing

Labour Party in Northern Ireland

Labour Party in Westminster

Other

Unofficial website with an archive of electoral manifestos and a directory of related websites

Labourhome - unofficial Labour Party grassroots

Labour History Group website

Unofficial history website

Guardian Unlimited Politics—Special Report: Labour Party

Labour Party aggregated news (multilingual)

Labour History Archive and Study Centre holds archives of the National Labour Party

( Translation accessible on

www.humaniteinenglish.com)

Category:Democratic socialism

Category:Edwardian era

Category:Labour parties

Category:Party of European Socialists member parties

Category:Political parties established in 1900

Category:Second International

Category:Social democratic parties in the United Kingdom

Category:Socialist International

Category:1900 establishments in the United Kingdom

af:Arbeidersparty (Verenigde Koninkryk)

ar:حزب العمال البريطاني

az:Leyboristlər Partiyası (Böyük Britaniya)

zh-min-nan:Lô-tōng Tóng (Liân-ha̍p Ông-kok)

br:Strollad Labour breizhveurat

bg:Лейбъристка партия

ca:Partit Laborista (Regne Unit)

cs:Labouristická strana

cy:Y Blaid Lafur (DU)

da:Labour

de:Labour Party

et:Leiboristlik Partei

el:Εργατικό κόμμα (Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο)

es:Partido Laborista (Reino Unido)

eo:Brita Laborista Partio

eu:Erresuma Batuko Alderdi Laborista

fa:حزب کارگر (بریتانیا)

fr:Parti travailliste (Royaume-Uni)

gl:Partido Laborista (Reino Unido)

ko:노동당 (영국)

id:Partai Buruh (Britania Raya)

is:Verkamannaflokkurinn (Bretlandi)

it:Partito Laburista (Regno Unito)

he:מפלגת הלייבור (בריטניה)

ka:ლეიბორისტული პარტია (გაერთიანებული სამეფო)

kw:Parti Lavur

la:Factio Laboris (Britanniarum Regnum)

lb:Labour Partei (Groussbritannien)

lt:Leiboristų partija

hu:Munkáspárt (Egyesült Királyság)

nl:Labour Party (Verenigd Koninkrijk)

new:लेबर पार्टि

ja:労働党 (イギリス)

no:Labour Party

nn:Det britiske arbeidarpartiet

pl:Partia Pracy (Wielka Brytania)

pt:Partido Trabalhista (Reino Unido)

ro:Partidul Laburist (Regatul Unit)

ru:Лейбористская партия (Великобритания)

sco:Labour Pairty (UK)

simple:Labour Party (UK)

sh:Laburistička stranka (UK)

fi:Työväenpuolue (Yhdistynyt kuningaskunta)

sv:Labour Party

tt:Бөекбританиянең Лейбористлар фиркасе

th:พรรคแรงงาน (สหราชอาณาจักร)

tr:İşçi Partisi (Britanya)

uk:Лейбористська партія (Великобританія)

vi:Đảng Lao động Anh

zh:工党 (英国)