- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2012 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Aaron Rodgers

Aaron Charles Rodgers (born December 2, 1983 in Chico, California, U.S.) is an American football quarterback for the Green Bay Packers of the NFL. Rodgers was drafted in the first round (24th overall) of the 2005 NFL Draft by the Green Bay Packers. Rodgers played college football at the University of California, Berkeley, where he set several school records, including lowest interception rate at 1.43%.

http://wn.com/Aaron_Rodgers -

Brett Favre

Brett Lorenzo Favre (; born October 10, 1969) is an American football quarterback in the National Football League. He is a 20-year veteran, having started at quarterback for the Green Bay Packers (1992–2007) and Minnesota Vikings (2009–present). He also played a single season each for the Atlanta Falcons (1991) and New York Jets (2008). Favre is the only quarterback in NFL history to throw for over 70,000 yards and the only quarterback to ever throw over 500 touchdowns.

http://wn.com/Brett_Favre -

Dan Marino

Daniel Constantine "Dan" Marino, Jr. (born September 15, 1961) is an American Hall of Fame former quarterback who played for the Miami Dolphins in the National Football League. The last quarterback of the Quarterback Class of 1983 to be taken in the first round, Marino became one of the most prolific quarterbacks in league history, holding or having held almost every major NFL passing record. Despite never being on a Super Bowl-winning team, he is recognized as one of the greatest quarterbacks in American football history. Remembered particularly for having a quick release and a powerful arm, Marino led the Dolphins into the playoffs ten times in his seventeen season career.

http://wn.com/Dan_Marino -

Donald Driver

Donald Jerome Driver (born February 2, 1975 in Houston, Texas) is an American football wide receiver who plays for the Green Bay Packers of the National Football League. Driver was picked by the Packers in the 1999 NFL Draft in the seventh round (213th pick overall) out of Alcorn State University.

http://wn.com/Donald_Driver

-

Beverly Hills

http://wn.com/Beverly_Hills -

Culver City

http://wn.com/Culver_City -

Italy

Italy (; ), officially the Italian Republic (), is a country located in south-central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia along the Alps. To the south it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Sardinia — the two largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea — and many other smaller islands. The independent states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy, whilst Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland. The territory of Italy covers some and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With 60.4 million inhabitants, it is the sixth most populous country in Europe, and the twenty-third most populous in the world.

http://wn.com/Italy -

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; , Spanish for "The Angels") is the second most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of California and the western United States, with a population of 3.83 million within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Los Angeles extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of over 14.8 million and it is the 14th largest urban area in the world, affording it megacity status. The metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is home to nearly 12.9 million residents while the broader Los Angeles-Long Beach-Riverside combined statistical area (CSA) contains nearly 17.8 million people. Los Angeles is also the seat of Los Angeles County, the most populated and one of the most multicultural counties in the United States. The city's inhabitants are referred to as "Angelenos" ().

http://wn.com/Los_Angeles

- 1582

- 30 February

- Aloysius Lilius

- Anno Domini

- Annunciation

- April

- August

- Augustus

- Battle of Agincourt

- Battle of Blenheim

- Bede

- birth of Jesus

- bissextile

- British Empire

- Brixham

- Byzantine Empire

- Calabria

- Calendar

- Calendar Act of 1750

- Calendar reform

- Charles I of England

- Christopher Clavius

- Church of Greece

- civil calendar

- Common Era

- Computus

- Council of Trent

- Crispin

- Dangun

- December

- decimal fraction

- Dionysius Exiguus

- dominical letter

- Doomsday (weekday)

- Doomsday algorithm

- Doomsday rule

- Dual dating

- Dutch Republic

- Easter

- epact

- Era System

- Etruscan mythology

- February

- Februus

- fever

- Finland

- First Nicene Council

- floor function

- Friday the 13th

- Gojoseon

- Gregory XIII

- Habsburg Monarchy

- HarperCollins

- Heisei period

- High Middle Ages

- Holocene calendar

- Holy Roman Empire

- integer

- Inter gravissimas

- intercalation

- ISO 8601

- January

- Janus (mythology)

- Japanese calendar

- Japanese era name

- Jean Meeus

- Johannes Kepler

- John Herschel

- Joseon Dynasty

- Juche calendar

- Julian calendar

- Julian day

- Julian day number

- Julius Caesar

- July

- June

- Juno (mythology)

- Kim Il Sung

- Kingdom of Ireland

- Korean era name

- Kuomintang

- Lady Day

- leap day

- leap second

- Leap week calendar

- leap year

- List of calendars

- Lorraine (province)

- Maia Maiestas

- March

- Mars (mythology)

- May

- mean tropical year

- Meiji period

- Metonic cycle

- Microsoft Word

- Middle Ages

- Miguel de Cervantes

- Mixed-style date

- mnemonic

- monk

- month

- musical keyboard

- Nativity of Jesus

- New calendarists

- North Korea

- November

- October

- October Revolution

- Old Calendarists

- Old Style

- Ole Rømer

- Oriental Orthodoxy

- Orthodox Churches

- papal bull

- Papal States

- Parilia

- Pax Calendar

- Pietro Pitati

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Propaganda Fide

- Protestantism

- Protestants

- Prussia

- Republic of China

- Republic of Venice

- Roman calendar

- Roman Empire

- Roman Republic

- Rome

- Romulus and Remus

- rotation

- Rudolphine Tables

- saint

- semitone

- September

- sexagesimal

- Showa period

- solar time

- Solstice

- Southern Hemisphere

- Southern Netherlands

- Soviet Decrees

- Sovnarkom

- Swedish calendar

- Symmetry454

- symposium

- Taisho period

- Taiwan

- tidal acceleration

- tropical year

- truncate

- Tuscany

- UNESCO

- vernal equinox

- warlord era of China

- week

- weekday

- William Hogarth

- William Shakespeare

- Winter solstice

- World Calendar

- year

- year zero

- Yu Kil-chun

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:44

- Published: 09 May 2009

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: BritainsGotTalent09

- Order: Reorder

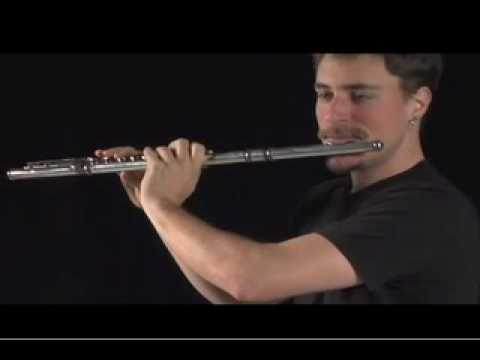

- Duration: 1:08

- Published: 19 Apr 2010

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: demetryjames86

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:20

- Published: 30 Nov 2009

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: freedomworksfilms

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:10

- Published: 18 Dec 2006

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: freedomworksfilms

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:25

- Published: 19 Jan 2007

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: freedomworksfilms

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:17

- Published: 15 Mar 2009

- Uploaded: 03 Jan 2012

- Author: xjanedoex17

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:44

- Published: 31 Dec 2011

- Uploaded: 06 Jan 2012

- Author: greganddonny

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:49

- Published: 02 Dec 2009

- Uploaded: 06 Jan 2012

- Author: damienwalters

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:26

- Published: 28 Nov 2011

- Uploaded: 06 Jan 2012

- Author: mediocrefilms2

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:14

- Published: 04 Jan 2007

- Uploaded: 06 Jan 2012

- Author: TrueFireTV

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:21

- Published: 30 Dec 2011

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: MediocreFilms

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:54

- Published: 26 Nov 2008

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: Starfuckerssss

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:49

- Published: 06 Feb 2009

- Uploaded: 15 Dec 2011

- Author: channelATEtv

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:57

- Published: 06 Jul 2007

- Uploaded: 07 Jan 2012

- Author: windhoek35

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:44

- Published: 26 Jun 2008

- Uploaded: 03 Jan 2012

- Author: DHDarkestHour

size: 1.5Kb

size: 4.7Kb

size: 105.0Kb

-

Eight dead after cruise ship runs aground off Italy

Jakarta Globe

Eight dead after cruise ship runs aground off Italy

Jakarta Globe

-

Obama Crossed the Rubicon, Again

WorldNews.com

Obama Crossed the Rubicon, Again

WorldNews.com

-

Tanker with crucial fuel delivery arrives off Nome

Austin American Statesman

Tanker with crucial fuel delivery arrives off Nome

Austin American Statesman

-

Iran leader says CIA, Mossad behind scientist's death

Gulf News

Iran leader says CIA, Mossad behind scientist's death

Gulf News

-

Captain held as cruise ship hits rock and sinks

The Independent

Captain held as cruise ship hits rock and sinks

The Independent

- 1582

- 30 February

- Aloysius Lilius

- Anno Domini

- Annunciation

- April

- August

- Augustus

- Battle of Agincourt

- Battle of Blenheim

- Bede

- birth of Jesus

- bissextile

- British Empire

- Brixham

- Byzantine Empire

- Calabria

- Calendar

- Calendar Act of 1750

- Calendar reform

- Charles I of England

- Christopher Clavius

- Church of Greece

- civil calendar

- Common Era

- Computus

- Council of Trent

- Crispin

- Dangun

- December

- decimal fraction

- Dionysius Exiguus

- dominical letter

- Doomsday (weekday)

- Doomsday algorithm

- Doomsday rule

- Dual dating

- Dutch Republic

- Easter

- epact

- Era System

- Etruscan mythology

- February

- Februus

- fever

- Finland

- First Nicene Council

- floor function

- Friday the 13th

- Gojoseon

- Gregory XIII

- Habsburg Monarchy

- HarperCollins

- Heisei period

- High Middle Ages

- Holocene calendar

- Holy Roman Empire

- integer

- Inter gravissimas

size: 2.0Kb

size: 9.2Kb

size: 4.4Kb

size: 4.3Kb

size: 3.1Kb

size: 2.6Kb

size: 1.9Kb

size: 0.5Kb

size: 5.8Kb

The Gregorian calendar reform contained two parts, a reform of the Julian calendar as used up to Pope Gregory's time, together with a reform of the lunar cycle used by the Church along with the Julian calendar for calculating dates of Easter. The reform was a modification of a proposal made by the Calabrian doctor Aloysius Lilius (or Lilio). Lilius' proposal included reducing the number of leap years in four centuries from 100 to 97, by making 3 out of 4 centurial years common instead of leap years: this part of the proposal had been suggested before by, among others, Pietro Pitati. Lilio also produced an original and practical scheme for adjusting the epacts of the moon for completing the calculation of Easter dates, solving a long-standing difficulty that had faced proposers of calendar reform.

The Gregorian calendar modified the Julian calendar's regular cycle of leap years, years exactly divisible by four, including all centurial years, as follows:

Every year that is exactly divisible by four is a leap year, except for years that are exactly divisible by 100; the centurial years that are exactly divisible by 400 are still leap years. For example, the year 1900 is not a leap year; the year 2000 is a leap year.

In addition to the change in the mean length of the calendar year from 365.25 days (365 days 6 hours) to 365.2425 days (365 days 5 hours 49 minutes 12 seconds), a reduction of 10 minutes 48 seconds per year, the Gregorian calendar reform also dealt with the past accumulated difference between these lengths. Between AD 325 (when the Roman Catholic Church thought the First Council of Nicaea had fixed the vernal equinox on 21 March), and the time of Pope Gregory's bull in 1582, the vernal equinox had moved backward in the calendar, until it was occurring on about 11 March, 10 days earlier. The Gregorian calendar therefore began by skipping 10 calendar days, to restore March 21 as the date of the vernal equinox.

Because of the Protestant Reformation, however, many Western European countries did not initially follow the Gregorian reform, and maintained their old-style systems. Eventually other countries followed the reform for the sake of consistency, but by the time the last adherents of the Julian calendar in Eastern Europe (Russia and Greece) changed to the Gregorian system in the 20th century, they had to drop 13 days from their calendars, due to the additional accumulated difference between the two calendars since 1582.

The Gregorian calendar continued the previous year-numbering system (Anno Domini), which counts years from the traditional date of the nativity, originally calculated in the 6th century and in use in much of Europe by the High Middle Ages. This year-numbering system is the predominant international standard today.

Description

The Gregorian solar calendar is an arithmetical calendar. It counts days as the basic unit of time, grouping them into years of 365 or 366 days; and repeats completely every 146,097 days, which fill 400 years, and which also happens to be 20,871 seven-day weeks. Of these 400 years, 303 common years have 365 days and 97 leap years have 366 days. This yields a calendar mean year of exactly 365+97/400 days = 365.2425 days = 365 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes and 12 seconds.A Gregorian year is divided into twelve months:

| No. | Name |

| 1 | January |

| 2 | February |

| 3 | March |

| 4 | April |

| 5 | May |

| 6 | June |

| 7 | July |

| 8 | August |

| 9 | September |

| 10 | October |

| 11 | November |

| 12 | December |

Although the month length pattern seems irregular, it can be represented by the arithmetic expression L = 30 + { [ M + floor(M/8) ] MOD 2 }, where L is the month length in days and M is the month number 1 to 12. The expression is valid for all 12 months, but for M = 2 (February) adjust by subtracting 2 and then if it is a leap year add 1.

A calendar date is fully specified by the year (numbered by some scheme beyond the scope of the calendar itself), the month (identified by name or number), and the day of the month (numbered sequentially starting at 1).

Leap years add a 29th day to February, which normally has 28 days. The essential ongoing differentiating feature of the Gregorian calendar, as distinct from the Julian calendar with a leap day every four years, is that the Gregorian omits 3 leap days every 400 years. This difference would have been more noticeable in modern memory were it not that the year 2000 was a leap year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendar systems.

The intercalary day in a leap year is known as a leap day. Since Roman times 24 February (bissextile) was counted as the leap day, but now 29 February is regarded as the leap day in most countries.

Although the calendar year runs from 1 January to 31 December, sometimes year numbers were based on a different starting point within the calendar. Confusingly, the term "Anno Domini" is not specific on this point, and actually refers to a family of year numbering systems with different starting points for the years. (See the section below for more on this issue.)

Lunar calendar

The Catholic Church maintained a tabular lunar calendar, which was primarily to calculate the date of Easter, and the lunar calendar required reform as well. A perpetual lunar calendar was created, in the sense that 30 different arrangements (lines in the expanded table of epacts) for lunar months were created. One of the 30 arrangements applies to a century (for this purpose, the century begins with a year divisible by 100). When the arrangement to be used for a given century is communicated, anyone in possession of the tables can find the age of the moon on any date, and calculate the date of Easter.

History

Gregorian reform

The motivation of the Catholic Church in adjusting the calendar was to celebrate Easter at the time it thought the First Council of Nicaea had agreed upon in 325. Although a canon of the council implies that all churches used the same Easter, they did not. The Church of Alexandria celebrated Easter on the Sunday after the 14th day of the moon (computed using the Metonic cycle) that falls on or after the vernal equinox, which they placed on 21 March. However, the Church of Rome still regarded 25 March as the equinox (until 342) and used a different cycle to compute the day of the moon. In the Alexandrian system, since the 14th day of the Easter moon could fall at earliest on 21 March its first day could fall no earlier than 8 March and no later than 5 April. This meant that Easter varied between 22 March and 25 April. In Rome, Easter was not allowed to fall later than 21 April, that being the day of the Parilia or birthday of Rome and a pagan festival. The first day of the Easter moon could fall no earlier than 5 March and no later than 2 April. Easter was the Sunday after the 15th day of this moon, whose 14th day was allowed to precede the equinox. Where the two systems produced different dates there was generally a compromise so that both churches were able to celebrate on the same day. By the 10th century all churches (except some on the eastern border of the Byzantine Empire) had adopted the Alexandrian Easter, which still placed the vernal equinox on 21 March, although Bede had already noted its drift in 725—it had drifted even further by the 16th century.Worse, the reckoned Moon that was used to compute Easter was fixed to the Julian year by a 19 year cycle. However, that approximation built up an error of one day every 310 years, so by the 16th century the lunar calendar was out of phase with the real Moon by four days.

The Council of Trent approved a plan in 1563 for correcting the calendrical errors, requiring that the date of the vernal equinox be restored to that which it held at the time of the First Council of Nicaea in 325 and that an alteration to the calendar be designed to prevent future drift. This would allow for a more consistent and accurate scheduling of the feast of Easter.

The fix was to come in two stages. First, it was necessary to approximate the correct length of a solar year. The value chosen was 365.2425 days in decimal notation. Although close to the mean tropical year of 365.24219 days, it is even closer to the mean vernal equinox year of 365.2424 days; this fact made the choice of approximation particularly appropriate as the purpose of creating the calendar was to ensure that the vernal equinox would be near a specific date (21 March). (See Accuracy).

The second stage was to devise a model based on the approximation which would provide an accurate yet simple, rule-based calendar. The formula designed by Aloysius Lilius was ultimately successful. It proposed a 10-day correction to revert the drift since Nicaea, and the imposition of a leap day in only 97 years in 400 rather than in 1 year in 4. To implement the model, it was provided that years divisible by 100 would be leap years only if they were divisible by 400 as well. So, in the last millennium, 1600 and 2000 were leap years, but 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not. In this millennium, 2100, 2200, 2300, 2500, 2600, 2700, 2900, and 3000, will not be leap years, but 2400, and 2800 will be. This theory was expanded upon by Christopher Clavius in a closely argued, 800 page volume. He would later defend his and Lilius's work against detractors.

The 19-year cycle used for the lunar calendar was also to be corrected by one day every 300 or 400 years (8 times in 2500 years) along with corrections for the years (1700, 1800, 1900, 2100 et cetera) that are no longer leap years. In fact, a new method for computing the date of Easter was introduced.

In 1577 a Compendium was sent to expert mathematicians outside the reform commission for comments. Some of these experts, including Giambattista Benedetti and Giuseppe Moleto, believed Easter should be computed from the true motions of the sun and moon, rather than using a tabular method, but these recommendations were not adopted.

Gregory dropped 10 days to bring the calendar back into synchronization with the seasons. Lilius originally proposed that the 10-day correction should be implemented by deleting the Julian leap day on each of its ten occurrences during a period of 40 years, thereby providing for a gradual return of the equinox to 21 March. However, Clavius's opinion was that the correction should take place in one move, and it was this advice which prevailed with Gregory. Accordingly, when the new calendar was put in use, the error accumulated in the 13 centuries since the Council of Nicaea was corrected by a deletion of ten days. The last day of the Julian calendar was Thursday, 4 October 1582 and this was followed by the first day of the Gregorian calendar, Friday, 15 October 1582 (the cycle of weekdays was not affected).

Adoption

Though Gregory's reform was enacted in the most solemn of forms available to the Church, in fact the bull had no authority beyond the Catholic Church and the Papal States. The changes which he was proposing were changes to the civil calendar over which he had no authority. The changes required adoption by the civil authorities in each country to have legal effect.The Nicene Council of 325 sought to devise rules whereby all Christians would celebrate Easter on the same day. In fact it took a very long time before Christians achieved that objective (see Easter for the issues which arose). However, the bull Inter gravissimas became the law of the Catholic Church. It was not recognised, however, by Protestant Churches nor by Orthodox Churches and others. Consequently, the days on which Easter and related holidays were celebrated by different Christian Churches again diverged.

Adoption in Europe

Only four Catholic countries adopted the new calendar on the date specified by the bull. Other Catholic countries experienced some delay before adopting the reform; and non-Catholic countries, not being subject to the decrees of the Pope, initially rejected or simply ignored the reform altogether, although they all eventually adopted it. Hence, the dates 5 October 1582 to 14 October 1582 (inclusive) are valid dates in many countries, but invalid in others.Spain, Portugal, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and most of Italy implemented the new calendar on Friday, 15 October 1582, following Julian Thursday, 4 October 1582. The Spanish and Portuguese colonies adopted the calendar later because of the slowness of communication. France adopted the new calendar on Monday, 20 December 1582, following Sunday, 9 December 1582. The Dutch provinces of Brabant, Zeeland and the Staten-Generaal also adopted it on 25 December of that year, the provinces forming the Southern Netherlands (modern Belgium) on 1 January 1583, and the province of Holland followed suit on 12 January 1583.

Many Protestant countries initially objected to adopting a Catholic invention; some Protestants feared the new calendar was part of a plot to return them to the Catholic fold. In the Czech lands, Protestants resisted the calendar imposed by the Habsburg Monarchy. In parts of Ireland, Catholic rebels until their defeat in the Nine Years' War kept the "new" Easter in defiance of the English-loyal authorities; later, Catholics practising in secret petitioned the Propaganda Fide for dispensation from observing the new calendar, as it signalled their disloyalty.

Denmark, which then included Norway and some Protestant states of Germany, adopted the solar portion of the new calendar on Monday, 1 March 1700, following Sunday, 18 February 1700, because of the influence of Ole Rømer, but did not adopt the lunar portion. Instead, they decided to calculate the date of Easter astronomically using the instant of the vernal equinox and the full moon according to Kepler's Rudolphine Tables of 1627. They finally adopted the lunar portion of the Gregorian calendar in 1776. The remaining provinces of the Dutch Republic also adopted the Gregorian calendar in July 1700 (Gelderland), December 1700 (Utrecht and Overijssel) and January 1701 (Friesland and Groningen).

Sweden's relationship with the Gregorian Calendar was a difficult one. Sweden started to make the change from the Julian calendar and towards the Gregorian calendar in 1700, but it was decided to make the (then 11-day) adjustment gradually, by excluding the leap days (29 February) from each of 11 successive leap years, 1700 to 1740. In the meantime, the Swedish calendar would be out of step with both the Julian calendar and the Gregorian calendar for 40 years; also, the difference would not be constant but would change every 4 years. This system had potential for confusion when working out the dates of Swedish events in this 40-year period. To add to the confusion, the system was poorly administered and the leap days that should have been excluded from 1704 and 1708 were not excluded. The Swedish calendar (according to the transition plan) should now have been 8 days behind the Gregorian, but was still in fact 10 days behind. King Charles XII recognised that the gradual change to the new system was not working, and he abandoned it.

However, rather than proceeding directly to the Gregorian calendar, it was decided to revert to the Julian calendar. This was achieved by introducing the unique date 30 February in the year 1712, adjusting the discrepancy in the calendars from 10 back to 11 days. Sweden finally adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1753, when Wednesday, 17 February was followed by Thursday, 1 March. Since Finland was under Swedish rule at that time, it did the same. Finland's annexation to the Russian Empire did not revert this, since autonomy was granted, but government documents in Finland were dated in both the Julian and Gregorian styles. This practice ended when independence was gained in 1917.

Britain and the British Empire (including the eastern part of what is now the United States) adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, by which time it was necessary to correct by 11 days. Wednesday, 2 September 1752 was followed by Thursday, 14 September 1752. Claims that rioters demanded "Give us our eleven days" grew out of a misinterpretation of a painting by William Hogarth. After 1753, the British tax year in Britain continued to operate on the Julian calendar and began on 5 April, which was the "Old Style" new tax year of 25 March. A 12th skipped Julian leap day in 1800 changed its start to 6 April. It was not changed when a 13th Julian leap day was skipped in 1900, so the tax year in the United Kingdom still begins on 6 April.

In Alaska, the change took place when Friday, 6 October 1867 was followed again by Friday, 18 October after the US purchase of Alaska from Russia, which was still on the Julian calendar. Instead of 12 days, only 11 were skipped, and the day of the week was repeated on successive days, because the International Date Line was shifted from Alaska's eastern to western boundary along with the change to the Gregorian calendar.

In Russia the Gregorian calendar was accepted after the October Revolution (so named because it took place in October 1917 in the Julian calendar). On 24 January 1918 the Council of People's Commissars issued a Decree that Wednesday, 31 January 1918 was to be followed by Thursday, 14 February 1918, thus dropping 13 days from the calendar.

The last country of Eastern Orthodox Europe to adopt the Gregorian calendar was Greece on Thursday, 1 March 1923, which followed Wednesday, 15 February 1923 (a change that also dropped 13 days).

Adoption in Eastern Asia

Japan replaced its traditional lunisolar calendar with the Gregorian calendar on , but adopted the numbered months it had used in its traditional calendar in place of European names, and continued to use Gengo, reign names, instead of the Common Era or Anno Domini system: Meiji 1=1868, Taisho 1=1912, Showa 1=1926, Heisei 1=1989, and so on. The "Western calendar" (西暦, seireki) is also widely accepted by civilians and to a lesser extent by government agencies.Korea adopted the Gregorian calendar on 1 January 1895 with the active participation of Yu Kil-chun. Although the new calendar continued to number its months, for its years during the Joseon Dynasty, 1895–97, these years were numbered from the founding of that dynasty, regarding year one as 1392. Between 1897 and 1910, and again from 1948 to 1962 Korean era names were used for its years. Between 1910 and 1945, when Korea was under Japanese rule, Japanese era names were used to count the years of the Gregorian calendar used in Korea. From 1945 until 1961 in South Korea, Gregorian calendar years were also counted from the foundation of Gojoseon in 2333 BCE (regarded as year one), the date of the legendary founding of Korea by Dangun, hence these Dangi (단기) years were 4278 to 4294. This numbering was informally used with the Korean lunar calendar before 1945 but is only occasionally used today. In North Korea, the Juche calendar has been used since 1997 to number its years, regarding year one as the birth of Kim Il Sung in 1912.

The Republic of China (ROC) formally adopted the Gregorian calendar at its founding on , but China soon descended into a period of warlordism with different warlords using different calendars. With the unification of China under the Kuomintang in October 1928, the Nationalist Government decreed that effective the Gregorian calendar would be used. However, China retained the Chinese traditions of numbering the months and a modified Era System, backdating the first year of the ROC to 1912; this system is still in use in Taiwan where the ROC government retains control. Upon its foundation in 1949, the People's Republic of China continued to use the Gregorian calendar with numbered months, but abolished the ROC Era System and adopted Western numbered years.

Adoption by Orthodox Churches

Despite all the civil adoptions, none of the national Orthodox Churches have recognised it for church or religious purposes. Instead, a Revised Julian calendar was proposed in May 1923 which dropped 13 days in 1923 and adopted a different leap year rule. There will be no difference between the two calendars until 2800. The Orthodox churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Greece, Cyprus, Romania, and Bulgaria adopted the Revised Julian calendar, so until 2800 these New calendarists would celebrate Christmas on 25 December in the Gregorian calendar, the same day as the Western churches. The Armenian Apostolic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1923, except in the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem where the old Julian calendar is still in use.The Orthodox churches of Jerusalem, Russia, Serbia, the Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Poland and the Greek Old Calendarists did not accept the Revised Julian calendar, and continue to celebrate Christmas on 25 December in the Julian calendar, which is 7 January in the Gregorian calendar until 2100. The refusal to accept the Gregorian reforms also has an impact on the date of Easter. This is because the date of Easter is determined with reference to 21 March as the functional equinox, which continues to apply in the Julian calendar, even though the civil calendar in the native countries now use the Gregorian calendar.

All of the other Eastern churches, the Oriental Orthodox churches (Coptic, Ethiopian, Eritrean, and Syrian) continue to use their own calendars, which usually result in fixed dates being celebrated in accordance with the Julian calendar but the Assyrian Church uses the Gregorian Calendar as enacted by Mar Dinkha, causing a schism; the Ancient Assyrian Church of the East continues to use the Julian Calendar.

All Eastern churches continue to use the Julian Easter with the sole exception of the Finnish Orthodox Church, which has adopted the Gregorian Easter.

Timeline

Period = from:1550 till:2050 TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal format:yyyy AlignBars = justify ScaleMinor=unit:year increment:50 start:1550 gridcolor:grilleMinor ScaleMajor=unit:year increment:100 start:1600 gridcolor:grilleMajor BackgroundColors=canvas:canvas bars:canvas BarData= bar:epoque barset:evennement

PlotData= bar:epoque shift:(0,0) width:30 from:start till:end color:gris # Arri?re plan

from:start till:1581 text:"Julian~calendar" color:rougeclair anchor:from from:1582 till:end text:"Gregorian calendar" color:rouge barset:evennement color:noir shift:(2,0) width:25

from:1582 till:1582 text:"1582~Spain, Portugal, and their possessions;~Italy, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth" shift:(2,5) from:1582 till:1582 text:"1582~France, Netherlands (Brabant, Zeeland and the Staten-Generaal), Savoy, Luxembourg" from:1583 till:1583 text:"1583~Austria, Netherlands (Holland and modern Belgium), Catholic Switzerland and Germany" from:1587 till:1587 text:"1587~Hungary" from:1605 till:1710 text:"1605-1710~Nova Scotia" color:bleuclair anchor:from from:1610 till:1610 text:"1610~Prussia" from:1582 till:1735 text:"1582-1735~Duchy of Lorraine" color:bleuclair anchor:from from:1648 till:1648 text:"1648~Alsace" from:1682 till:1682 text:"1682~Strasbourg" from:1700 till:1701 text:"1700~Protestant Germany, Netherlands (the northern provinces), Switzerland;~Denmark (incl. Norway and Iceland)" shift:(2,5) from:1753 till:1753 text:"1753~Sweden (incl. Finland)"

#To start again the indentation in top barset:break at:1752 #blank line at:1752 #blank line at:1752 #blank line at:1752 #blank line from:1752 till:1752 text:"1752~Great Britain and its possessions" at:1760 #blank line from:1760 till:1760 text:"1760~Lorraine (Habsburg → France)" at:1584 #blank line at:1584 #blank line from:1584 till:1584 text:"1584~Bohemia and Moravia"

#To start again the indentation in top barset:break from:1811 till:1811 text:"1811~Swiss canton of Grisons" from:1867 till:1867 text:"1867~Alaska (Russia → USA)" from:1873 till:1873 text:"1873~Japan" from:1875 till:1875 text:"1875~Egypt" from:1896 till:1896 text:"1896~Korea" from:1912 till:1912 text:"1912~Albania" from:1915 till:1915 text:"1915~Latvia, Lithuania" from:1916 till:1916 text:"1916~Bulgaria" from:1918 till:1918 text:"1918~Russia, Estonia" from:1919 till:1919 text:"1919~Romania, Yugoslavia from:1922 till:1922 text:"1922~USSR" from:1923 till:1923 text:"1923~Greece" from:1926 till:1926 text:"1926~Turkey"

#To start again the indentation in top barset:break from:1912 till:1912 text:"1912 & 1929~China" shift:(2,5)

The date when each country adopted the Gregorian calendar, or an equivalent, is marked against a horizontal time line. The vertical axis is used for expansion to show separate national names for ease in charting, but otherwise has no significance.

Difference between Gregorian and Julian calendar dates

Since the introduction of the Gregorian calendar, the difference between Gregorian and Julian calendar dates has increased by three days every four centuries:

| Gregorian range | Julian range | |

| From 15 October 1582to 10 March 1700 | From 5 October 1582to 28 February 1700 | |

| From 11 March 1700to 11 March 1800 | From 29 February 1700to 28 February 1800 | |

| From 12 March 1800to 12 March 1900 | From 29 February 1800to 28 February 1900 | |

| From 13 March 1900to 13 March 2100 | From 29 February 1900to 28 February 2100 | |

| From 14 March 2100to 14 March 2200 | From 29 February 2100to 28 February 2200 |

A more extensive list is available at Conversion between Julian and Gregorian calendars.

This section always places the intercalary day on even though it was always obtained by doubling (the bissextum (twice sixth) or bissextile day) until the late Middle Ages. The Gregorian calendar is proleptic before 1582 (assumed to exist before 1582) while the Julian calendar is proleptic before year AD 1 (because non-quadrennial leap days were used between 45 BC and AD 1).

The following equation gives the number of days (actually, dates) that the Gregorian calendar is ahead of the Julian calendar, called the secular difference between the two calendars. A negative difference means the Julian calendar is ahead of the Gregorian calendar. : where is the secular difference; is the hundreds digits of the year using astronomical year numbering, that is, use for BC years; and is the floor function of . The floor function truncates (removes) any decimal fraction of a positive real number (), but avoids the ambiguity of truncating a negative number containing a decimal fraction by returning the more negative of its neighboring integers ().

The calculated difference increases by one in a centurial year (a year ending in '00) at either Julian or Gregorian, whichever is later. For positive differences, Julian is later, whereas for negative differences, Gregorian is later.

Beginning of the year

The year used in dates during the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire was the consular year, which began on the day when consuls first entered office—probably 1 May before 222 BC, 15 March from 222 BC and 1 January from 153 BC. The Julian calendar, which began in 45 BC, continued to use 1 January as the first day of the new year. Even though the year used for dates changed, the civil year always displayed its months in the order January through December from the Roman Republican period until the present.During the Middle Ages, under the influence of the Christian Church, many Western European countries moved the start of the year to one of several important Christian festivals—25 December (the Nativity of Jesus), 25 March (Annunciation), or Easter (France), while the Byzantine Empire began its year on 1 September and Russia did so on 1 March until 1492 when the year was moved to 1 September.

In common usage, 1 January was regarded as New Year's Day and celebrated as such, but from the 12th century until 1751 the legal year in England began on 25 March (Lady Day). So, for example, the Parliamentary record lists the execution of Charles I as occurring in 1648 (as the year did not end until 24 March), although modern histories adjust the start of the year to 1 January and record the execution as occurring in 1649.

Most Western European countries changed the start of the year to 1 January before they adopted the Gregorian calendar. For example, Scotland changed the start of the Scottish New Year to 1 January in 1600 (this means that 1599 was a short year). England, Ireland and the British colonies changed the start of the year to 1 January in 1752 (so 1751 was a short year with only 282 days). Later that year in September the Gregorian calendar was introduced throughout Britain and the British colonies (see the section Adoption). These two reforms were implemented by the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750.

In some countries, an official decree or law specified that the start of the year should be 1 January. For such countries we can identify a specific year when a 1 January-year became the norm. But in other countries the customs varied, and the start of the year moved back and forth as fashion and influence from other countries dictated various customs.

| Country | Start numbered yearon 1 January | |

| Denmark | Gradual change from13th to 16th centuries | |

| Republic of Venice | Venice | 1522 |

| Holy Roman Empire | 1544 | |

| Spain | 1556 | |

| Portugal | 1556 | |

| Prussia | 1559 | |

| Sweden | 1559 | |

| France | 1564 | |

| Southern Netherlands | 1576 | |

| Lorraine (province) | Lorraine | 1579 |

| Dutch Republic | 1583 | |

| Scotland | 1600 | |

| Russia | 1700 | |

| Tuscany | 1721 | |

| Kingdom of Great Britain | Britain andBritish Empireexcept Scotland | 1752 |

Neither the papal bull nor its attached canons explicitly fix such a date, though it is implied by two tables of saint's days, one labelled 1582 which ends on 31 December, and another for any full year that begins on 1 January. It also specifies its epact relative to 1 January, in contrast with the Julian calendar, which specified it relative to 22 March. These would have been the inevitable result of the above shift in the beginning of the Julian year.

Dual dating

During the period between 1582, when the first countries adopted the Gregorian calendar, and 1923, when the last European country adopted it, it was often necessary to indicate the date of some event in both the Julian calendar and in the Gregorian calendar, for example, "10/21 February 1750/51", where the dual year accounts for some countries already beginning their numbered year on 1 January while others were still using some other date. Even before 1582, the year sometimes had to be double dated because of the different beginnings of the year in various countries. Woolley, writing in his biography of John Dee (1527–1608/9), notes that immediately after 1582 English letter writers "customarily" used "two dates" on their letters, one OS and one NS.

Old Style and New Style dates

"Old Style" (OS) and "New Style" (NS) are sometimes added to dates to identify which system is used in the British Empire and other countries that did not immediately change. Because the Calendar Act of 1750 altered the start of the year, and also aligned the British calendar with the Gregorian calendar, there is some confusion as to what these terms mean. They can indicate that the start of the Julian year has been adjusted to start on 1 January (NS) even though contemporary documents use a different start of year (OS); or to indicate that a date conforms to the Julian calendar (OS), formerly in use in many countries, rather than the Gregorian calendar (NS).

Proleptic Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar can, for certain purposes, be extended backwards to dates preceding its official introduction, producing the proleptic Gregorian calendar. However, this proleptic calendar should be used with great caution.For ordinary purposes, the dates of events occurring prior to 15 October 1582 are generally shown as they appeared in the Julian calendar, with the year starting on 1 January, and no conversion to their Gregorian equivalents. The Battle of Agincourt is universally known to have been fought on 25 October 1415 which is Saint Crispin's Day.

Usually, the mapping of new dates onto old dates with a start of year adjustment works well with little confusion for events which happened before the introduction of the Gregorian Calendar. But for the period between the first introduction of the Gregorian calendar on 15 October 1582 and its introduction in Britain on 14 September 1752, there can be considerable confusion between events in continental western Europe and in British domains in English language histories. Events in continental western Europe are usually reported in English language histories as happening under the Gregorian calendar. For example the Battle of Blenheim is always given as 13 August 1704. However confusion occurs when an event affects both. For example William III of England arrived at Brixham in England on 5 November (Julian calendar), after setting sail from the Netherlands on 11 November (Gregorian calendar).

Shakespeare and Cervantes apparently died on exactly the same date (23 April 1616), but in fact Cervantes predeceased Shakespeare by ten days in real time (for dating these events, Spain used the Gregorian calendar, but Britain used the Julian calendar). This coincidence, however, historically encouraged UNESCO to make 23 April the World Book and Copyright Day.

Astronomers avoid this ambiguity by the use of the Julian day number.

For dates before the year 1, unlike the proleptic Gregorian calendar used in the international standard ISO 8601, the traditional proleptic Gregorian calendar (like the Julian calendar) does not have a year 0 and instead uses the ordinal numbers 1, 2, … both for years AD and BC. Thus the traditional time line is 2 BC, 1 BC, AD 1, and AD 2. ISO 8601 uses astronomical year numbering which includes a year 0 and negative numbers before it. Thus the ISO 8601 time line is -0001, 0000, 0001, and 0002.

Months of the year

English speakers sometimes remember the number of days in each month by the use of the traditional mnemonic verse::Thirty days hath September, :April, June, and November. :All the rest have thirty-one, :Excepting February alone, :Which hath twenty-eight days clear, :And twenty-nine in each leap year.

For variations and alternate endings, see Thirty days hath September.

A language-independent alternative used in many countries is to hold up one's two fists with the index knuckle of the left hand against the index knuckle of the right hand. Then, starting with January from the little knuckle of the left hand, count knuckle, space, knuckle, space through the months. A knuckle represents a month of 31 days, and a space represents a short month (a 28- or 29-day February or any 30-day month). The junction between the hands is not counted, so the two index knuckles represent July and August. This method also works by starting the sequence on the right hand's little knuckle, then continuing towards the left. It can also be done using just one hand: after counting the fourth knuckle as July, start again counting the first knuckle as August. A similar mnemonic can be found on a piano keyboard: starting on the key F for January, moving up the keyboard in semitones, the black notes give the short months, the white notes the long ones.

The Origins of English naming used by the Gregorian calendar:

Week

In conjunction with the system of months there is a system of weeks. A physical or electronic calendar provides conversion from a given date to the weekday, and shows multiple dates for a given weekday and month. Calculating the day of the week is not very simple, because of the irregularities in the Gregorian system. When the Gregorian calendar was adopted by each country, the weekly cycle continued uninterrupted. For example, in the case of the few countries that adopted the reformed calendar on the date proposed by Gregory XIII for the calendar's adoption, Friday, 15 October 1582, the preceding date was Thursday, 4 October 1582 (Julian calendar).

Distribution of dates by day of the week

Since the 400-year cycle of the Gregorian calendar consists of a whole number of weeks, each cycle has a fixed distribution of weekdays among calendar dates. It then becomes possible that this distribution is not even.

Indeed, because there are 97 leap years in every 400 years in the Gregorian Calendar, there are on average leap years for each starting weekday in each cycle. This already shows that the frequency is not the same for each weekday (indeed, to be the same, this number must be an integer), which is due to the effects of the "common" centennial years (1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200, etc.).

The absence of an extra day in such years causes the following leap year (1704, 1804, 1904, 2104, etc.) to start on the same day of the week as the leap year twelve years before (1692, 1792, 1892, 2092 etc.). Similarly, the leap year eight years after a "common" centennial year (1708, 1808, 1908, 2108, etc.) starts on the same day of the week as the leap year immediately prior to the "common" centennial year (1696, 1796, 1896, 2096 etc.). Thus, those days of the week on which such leap years begin gain an extra year or two in each cycle.

The following table shows the distribution of extra days during each 400-year cycle:

| Occurrences | Leap year starts on | |

| 15 | Wednesday | |

| 13 | Thursday | |

| 14 | Friday | |

| 14 | Saturday | |

| 13 | Sunday | |

| 15 | Monday | |

| 13 | Tuesday |

Note that as a cycle, this pattern is symmetric with respect to the low Saturday value.

A leap year starting on Sunday means the next year does not start on Monday, so more leap years starting on Sunday means fewer years starting on Monday, etc. Thus the pattern of number of years starting on each day is inverted and shifted by one weekday: 58, 56, 58, 57, 57, 58, 56 (symmetric with respect to the high Sunday value).

The number of common years starting on each day is found by subtraction: 43, 43, 44, 43, 44, 43, 43.

The frequency of a particular date being on a particular weekday can easily be derived from the above (for dates in March and later, relate them to the next New Year).

See also the cycle of Doomsdays.

Accuracy

The Gregorian calendar improves the approximation made by the Julian calendar by skipping three Julian leap days in every 400 years, giving an average year of 365.2425 mean solar days long. This approximation has an error of about one day per 3,300 years with respect to the mean tropical year. However, because of the precession of the equinoxes, the error with respect to the vernal equinox (which occurs, on average, 365.24237 days apart near 2000) is 1 day every 7,700 years. By any criterion, the Gregorian calendar is substantially more accurate than the 1 day in 128 years error of the Julian calendar (average year 365.25 days).In the 19th century, Sir John Herschel proposed a modification to the Gregorian calendar with 969 leap days every 4000 years, instead of 970 leap days that the Gregorian calendar would insert over the same period. This would reduce the average year to 365.24225 days. Herschel's proposal would make the year 4000, and multiples thereof, common instead of leap. While this modification has often been proposed since, it has never been officially adopted.

On time scales of thousands of years, the Gregorian calendar falls behind the seasons because the slowing down of the Earth's rotation makes each day slightly longer over time (see tidal acceleration and leap second) while the year maintains a more uniform duration. Borkowski reviewed mathematical models in the literature, and found that the results generally fall between a model by McCarthy and Babcock, and another by Stephenson and Morrison. If so, in the year 4000, the calendar will fall behind by at least 0.8 but less than 1.1 days. In the year 12,000 the calendar would fall behind by at least 8 but less than 12 days.

Calendar seasonal error

This image shows the difference between the Gregorian calendar and the seasons.

The y-axis is the date in June and the x-axis is Gregorian calendar years.

Each point is the date and time of the June Solstice (or Winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere) on that particular year. The error shifts by about a quarter of a day per year. Centurial years are ordinary years, unless they are divisible by 400, in which case they are leap years. This causes a correction on years 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200, and 2300.

For instance, these corrections cause 23 December 1903 to be the latest December solstice, and 20 December 2096 to be the earliest solstice—2.25 days of variation compared with the seasonal event.

Leap seconds and other aspects

Since 1972, some years may also contain one or more leap seconds, to account for cumulative irregularities in the Earth's rotation. So far, these have always been positive and have occurred on average once every 18 months.The day of the year is somewhat inconvenient to compute, partly because the leap day does not fall at the end of the year. But the calendar exhibits a repeating pattern for the number of days in the months March through July and August through December: 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, for a total of 153 days each. In fact, any five consecutive months not containing February contain exactly 153 days.

See also common year starting on Sunday and dominical letter.

The 400-year cycle of the Gregorian calendar has 146,097 days and hence exactly 20,871 weeks. So, for example, the days of the week in Gregorian 1603 were exactly the same as for 2003. The years that are divisible by 400 begin on a Saturday. In the 400-year cycle, more months begin on a Sunday (and hence have Friday the 13th) than any other day of the week (see above under Week for a more detailed explanation of how this happens). 688 out of every 4800 months (or 172/1200) begin on a Sunday, while only 684 out of every 4800 months (171/1200) begin on each of Saturday and Monday, the least common cases.

A smaller cycle is 28 years (1,461 weeks), provided that there is no dropped leap year in between. Days of the week in years may also repeat after 6, 11, 12, 28 or 40 years. Intervals of 6 and 11 are only possible with common years, while intervals of 28 and 40 are only possible with leap years. An interval of 12 years only occurs with common years when there is a dropped leap year in between.

The Doomsday algorithm is a method to discern which of the 14 calendar variations should be used in any given year (after the Gregorian reformation). It is based on the last day in February, referred to as the Doomsday.

Day of the week for a date in different years

Common years always begin and end on the same day of the week, since 365 is one more than a multiple of 7 (52 [number of weeks in a year] × 7 [number of days in a week] = 364). For example, 2003 began on a Wednesday and ended on a Wednesday. Leap years end on the next day of the week from which they begin. For example, 2004 began on a Thursday and ended on a Friday.Not counting leap years, any calendar date will move to the next day of the week the following year. For example, if a birthday fell on a Tuesday in 2002, it fell on a Wednesday in 2003. Leap years make things a little more complicated, and move any given date occurring after March two days in the week on the following year, "leaping over" an extra day, hence the term leap year. For example, 2004 was a leap year, so calendar days of 1 March or later in the year, moved two days of the week from 2003.

Calendar days occurring before 1 March do not make the extra day of the week jump until the year following a leap year. So, if a birthday is 15 June, then it must have fallen on a Sunday in 2003 and a Tuesday in 2004. If, however, a birthday is 15 February, then it must have fallen on a Saturday in 2003, a Sunday in 2004 and a Tuesday in 2005.

Calendar matches between months

In any year (even a leap year), July always begins on the same day of the week that April does; therefore, the only difference between a July calendar page and an April calendar page in the same year is the extra day July has. The same relationship exists between September and December, as well as between March and November: if an extra day is added to the September calendar, the calendar for December is obtained; remove a day from the March calendar, and that for November is obtained.In common years (non-leap years), there are additional matches: October duplicates January, and March and November duplicate February in their first 28 days. In leap years only, there is a different set of additional matches: July is a duplicate of January, while February is duplicated in the first 29 days of August.

English names for year numbering system

The Anno Domini (Latin for "in the year of the/our Lord") system of numbering years, in which the leap year rules are written, and which is generally used together with the Gregorian calendar, is also known in English as the Common Era or Christian Era. Years before the beginning of the era are known in English as Before Christ, Before the Common Era, or Before the Christian Era. The corresponding abbreviations AD, CE, BC, and BCE are used. There is no year 0; AD 1 immediately follows 1 BC.Naturally, since Inter gravissimas was written in Latin, it does not mandate any English language nomenclature. Two era names occur within the bull, "anno Incarnationis dominicæ" ("in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord") for the year it was signed, and "anno à Nativitate Domini nostri Jesu Christi" ("in the year from the Nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ") for the year it was printed. Nevertheless, "anno Domini" and its inflections "anni Domini" and "annus Domini" are used many times in the canons attached to the bull.

Proposed reforms

The following are proposed reforms of the Gregorian calendar:

See also

Notes

References

External links

Category:1582 establishments Category:Gregorian calendar Category:Calendars Category:Roman calendar

af:Gregoriaanse kalender als:Gregorianischer Kalender am:ጎርጎርያን ካሌንዳር ang:Gregorisce ȝerīmbōc ar:تقويم ميلادي an:Calandario gregorián arc:ܣܘܪܓܕܐ ܓܪܝܓܘܪܝܐ ast:Calendariu gregorianu az:Qriqorian təqvimi bn:গ্রেগরিয়ান বর্ষপঞ্জী zh-min-nan:Gregorius Le̍k-hoat map-bms:Kalendher Gregorian ba:Григориан календары be:Грыгарыянскі каляндар be-x-old:Грэгарыянскі каляндар bar:Gregorianischa Kalenda bs:Gregorijanski kalendar br:Deiziadur gregorian bg:Григориански календар ca:Calendari gregorià ceb:Kalendaryong Gregoryano cs:Gregoriánský kalendář cbk-zam:Calendario Gregoriano cy:Calendr Gregori da:Gregorianske kalender de:Gregorianischer Kalender dv:މީލާދީ ކަލަންޑަރު et:Gregoriuse kalender el:Γρηγοριανό ημερολόγιο eml:Lunâri Gregoriân es:Calendario gregoriano eo:Gregoria kalendaro eu:Gregoriotar egutegia fa:گاهشماری میلادی fo:Gregorianski kalendarin fr:Calendrier grégorien fy:Gregoriaanske kalinder fur:Calendari Gregorian gl:Calendario gregoriano gu:ગ્રેગોરીયન પંચાંગ ko:그레고리력 hi:ग्रेगोरी कैलेंडर hr:Gregorijanski kalendar io:Gregoriana kalendario ilo:Calendario a Gregorian bpy:গ্রেগরিয়ান পাঞ্জী id:Kalender Gregorian ia:Calendario gregorian is:Gregoríska tímatalið it:Calendario gregoriano he:הלוח הגרגוריאני jv:Pananggalan Gregorian kl:Gregorianskit ullorsiutaat kn:ಗ್ರೆಗೋರಿಯನ್ ಕ್ಯಾಲೆಂಡರ್ krc:Григориан орузлама ka:გრიგორიანული კალენდარი csb:Gregorijansczi kalãdôrz kk:Грегориан күнтізбесі kw:Calans gregorek sw:Kalenda ya Gregori ht:Almanak gregoryen ku:Salnameya Gregorî la:Calendarium Gregorianum lv:Gregora kalendārs lb:Gregorianesche Kalenner lt:Grigaliaus kalendorius lij:Lûnäio Gregorian li:Gregoriaanse kalender hu:Gergely-naptár mk:Грегоријански календар ml:ഗ്രിഗോറിയൻ കാലഗണനാരീതി arz:تقويم جريجورى ms:Kalendar Gregory mn:Григорийн тоолол nah:Gregorio xiuhpōhualli nl:Gregoriaanse kalender nds-nl:Gregoriaanse kelender ne:ग्रेगोरी क्यालेण्डर ja:グレゴリオ暦 nap:Calannario greguriano no:Gregoriansk kalender nn:Den gregorianske kalenderen nrm:Calendri grégorian oc:Calendièr gregorian mhr:Григориан кечышот or:ଗ୍ରେଗୋରି ପାଞ୍ଜି uz:Grigoriy taqvimi pa:ਗ੍ਰੈਗਰੀ ਕਲੰਡਰ pnb:گریگری کلنڈر nds:Gregoriaansch Klenner pl:Kalendarz gregoriański pnt:Γρηγοριανόν ημερολόγιον pt:Calendário gregoriano ro:Calendarul gregorian qu:Griguryanu kalindaryu rue:Ґреґоріаньскый календарь ru:Григорианский календарь sah:Грегориан халандаара sco:Gregorian calendar sq:Kalendari Gregorian scn:Calannariu grigurianu si:ග්රෙගරි දින දසුන simple:Gregorian calendar sk:Gregoriánsky kalendár sl:Gregorijanski koledar ckb:ڕۆژژمێری زایینی sr:Грегоријански календар sh:Gregorijanski kalendar su:Kalénder Grégori fi:Gregoriaaninen kalenteri sv:Gregorianska kalendern tl:Kalendaryong Gregoryano ta:கிரெகொரியின் நாட்காட்டி tt:Милади тәкъвиме te:గ్రెగోరియన్ కేలండర్ th:ปฏิทินเกรโกเรียน tr:Gregoryen takvim uk:Григоріанський календар ur:عیسوی تقویم vec:Całendario gregorian vi:Lịch Gregory fiu-vro:Gregoriusõ kallendri wa:Calindrî grigoryin zh-classical:格里曆 war:Kalendaryo Gregoryano yi:גרעגאריאנישער קאלענדאר yo:Kàlẹ́ndà Gregory zh-yue:公曆 bat-smg:Grėgaliaus kalėnduorios zh:公历

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Currentteam | Green Bay Packers |

|---|---|

| Currentnumber | 85 |

| Currentposition | Wide receiver |

| Birth date | September 21, 1983 |

| Birth place | Kalamazoo, Michigan |

| Heightft | 5 |

| Heightin | 11 |

| Weight | 198 |

| Debutyear | 2006 |

| Debutteam | Green Bay Packers |

| Highlights | |

| College | Western Michigan |

| Draftyear | 2006 |

| Draftround | 2 |

| Draftpick | 52 |

| Pastteams | |

| Statseason | 2010 |

| Statlabel1 | Receptions |

| Statvalue1 | 322 |

| Statlabel2 | Receiving yards |

| Statvalue2 | 5,222 |

| Statlabel3 | Receiving touchdowns |

| Statvalue3 | 40 |

| Nfl | JEN480468 }} |

Gregory Jennings, Jr. (born September 21, 1983) is a professional American football wide receiver for the Green Bay Packers of the National Football League. He was drafted out of Western Michigan University in the second round, 52nd overall, of the 2006 NFL Draft.

High school career

Jennings attended Kalamazoo Central High School where he was all conference in three sports—football, basketball and track. Jennings played wide receiver, running back, outside linebacker and defensive back as a three-time letterman for the football team. He was listed 11th on the "Fab 50" rankings of the Detroit Free Press as a senior. Jennings finished seventh in voting for Mr. Basketball of Michigan in 2000–01 and scored a school record 50 points in a losing effort against Benton Harbor as a senior.

College career

Greg Jennings attended Western Michigan University. He finished his career there with 238 receptions for 3539 yards and 39 touchdowns. Jennings was a red-shirt freshman. He missed 8 games due to a broken ankle bone. In the 8 games he did play, he caught 10 passes for 138 yards. In 2003, he was second on the Broncos with 56 catches for 1,050 yards and 14 touchdowns. He finished the 2003 season with 1,734 all-purpose yards. He was named to the second team All-Mid American team. In 2004, he led the Broncos with 74 catches for 1,092 yards and 11 touchdowns. He tallied 1,415 all-purpose yards. He was named to the All-MAC team. In 2005, he had 98 catches, and led the nation in catches per game, with 8.91. He had 1,259 yards with 14 touchdowns, and earned the 2005 MAC Offensive Player of the Year Award. His 5,093 all-purpose yards is a WMU record, and ranks 8th in MAC history. Jennings became only the 11th player to gain over 1,000 yards in at least three seasons of a college career. Jennings graduated from WMU in 2010 after completing the 16 credits he needed through "self-instructional" classes.

Professional career

Green Bay

The Green Bay Packers drafted Jennings in the 2nd round (52nd pick overall) of the 2006 NFL draft. Jennings signed to a four-year contract on July 25, 2006. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported the deal was worth $2.85 million, including a $1.24 million signing bonus.Jennings was named the starting wide receiver, along with Donald Driver, which put Robert Ferguson in the slot, for his first professional regular season game Green Bay Packers by head coach Mike McCarthy on September 2, 2006. Jennings led the NFL in receiving yardage during the 2006 preseason. He had 1 catch for 5 yards in his first game.

On September 24, 2006, he caught a 75-yard TD pass from Brett Favre against the Detroit Lions. It was Favre's 400th TD pass for his career, a milestone reached only by Favre and Dan Marino. This was also Jennings' first 100-plus yard game, as he finished with 3 catches, 101 yds and 1 touchdown. Jennings was voted NFL Rookie of the Week for games played September 24–25, 2006, the only time he received this honor. Jennings was also named to the NFL All Rookie team at the end of the season.

On September 23, 2007, Jennings caught a game-winning 57-yard TD pass from Favre with less than two minutes to play to help beat the San Diego Chargers 31–24 at Lambeau Field and improve the team's record to 3–0 in 2007. This was Jennings' 1st touchdown catch in 2007, as well as Favre's 420th career touchdown pass, tying him with Dan Marino for the most TD passes in NFL history.

A week later on September 30, 2007, during a 23–16 victory over the Minnesota Vikings, Jennings caught a 16-yard pass from Brett Favre that opened the scoring 10 minutes into the first quarter, and broke the all-time touchdown pass record Favre had shared with Dan Marino. On October 29, 2007, Jennings caught an 82-yard touchdown pass from Favre to defeat the Denver Broncos 19–13 in overtime, tying him for the second longest overtime touchdown in NFL history. Then the following week, he caught the game-winning touchdown pass that went for 60 yards to beat the Chiefs in Kansas City. Against the Cowboys on November 29, 2007, in a game broadcast on the NFL network, Jennings hauled in the first ever touchdown pass by quarterback Aaron Rodgers.

Jennings and running back Ryan Grant each had a touchdown during a 33–14 victory over the St. Louis Rams on December 16, 2007, making it the first time two Packers players have each scored a touchdown in the same four consecutive games. Jennings collected 80 receptions for 1292 yards and 9 touchdowns in the 2008 season.

On June 23, 2009 Jennings received a new three year extension which will pay him $26.35 million and includes $16M guaranteed. It also includes a $11.25 million signing bonus. Jennings caught another game winning pass on September 13, 2009 to defeat the Chicago Bears in the season opener. Aaron Rodgers hit Jennings down the middle for a 50 yard score with less than two minutes in regulation. In the Packers 2009 Wild Card game against the Arizona Cardinals, Jennings had 8 receptions for 130 yards, scoring 1 touchdown. He has spent his entire career with the Packers. In the 2010-2011 season, Jennings helped the packers go 10-6 in the regular season. In Super Bowl XLV, on February 6, 2011, Jennings caught four passes for 64 yards and scored two touchdowns in the Packers' 31–25 victory over the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Regular season statistics

| Season !! Team !! G !! GS !! Rec !! Yds !! Avg !! Long !! TDs | |||||||||

| 2006 NFL Season | 2006 | 2006 Green Bay Packers season>Green Bay Packers | 14| | 11 | 45 | 632 | 14.0 | 75 | 3 |

| 2007 NFL Season | 2007 | 2007 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 13 | 13 | 53 | 920 | 17.4 | 82 | 12 |

| 2008 NFL Season | 2008 | 2008 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 16 | 15 | 80 | 1,292 | 16.2 | 63 | 9 |

| 2009 NFL Season | 2009 | 2009 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 16 | 13 | 68 | 1,113 | 16.4 | 83 | 4 |

| 2010 NFL Season | 2010 | 2010 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 16 | 16 | 76 | 1,265 | 16.6 | 86 | 12 |

| Total | | | 75 | 68 | 322 | 5,222 | 16.2 | 86 | 40 |

Playoff statistics

| Year !! Team !! G !! GS !! Rec !! Yds !! Avg !! TDs | ||||||||

| 2007-08 NFL playoffs | 2007–08 | 2007 Green Bay Packers season>Green Bay Packers | 2| | 2 | 7 | 85 | 12.1 | 2 |

| 2009-10 NFL playoffs | 2009–10 | 2009 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 1 | 1 | 8 | 130 | 16.3 | 1 |

| 2010-11 NFL playoffs | 2010–11 | 2010 Green Bay Packers seasonGreen Bay Packers || | 4 | 4 | 21 | 303 | 14.4 | 2 |

| Total | | | 7 | 7 | 36 | 518 | 14.3 | 5 |

Acting career

On May 5, 2010, Jennings made an appearance on the CBS prime time hit show Criminal Minds. He portrayed a lab technician working at a crime scene. Jennings is also in discussions to appear on BET's The Game. He appeared as himself on the July 6, 2011, episode of Royal Pains.

Family

Greg Jennings is married to his wife Nicole, also of Kalamazoo, and they have three daughters named Amya, Alea and Ayva.

References

External links

Category:American football wide receivers Category:Green Bay Packers players Category:Western Michigan Broncos football players Category:Players of American football from Michigan Category:People from Kalamazoo, Michigan Category:1983 births Category:Living people

da:Greg Jennings de:Greg Jennings es:Greg Jennings fr:Greg JenningsThis text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| show name | Curb Your Enthusiasm |

|---|---|

| genre | Comedy |

| camera | Single-camera |

| runtime | 30 minutes |

| creator | Larry David |

| starring | Larry DavidJeff GarlinCheryl HinesSusie Essman |

| executive producer | Larry DavidJeff GarlinRobert B. WeideAlec BergDavid MandelJeff SchafferLarry CharlesGavin PoloneTim GibbonsErin O'Malley |

| writer | Larry David |

| opentheme | "Frolic" |

| theme music composer | Luciano Michelini |

| country | United States |

| language | English |

| num seasons | 8 |

| num episodes | 78 (plus 60-minute special) |

| list episodes | List of Curb Your Enthusiasm episodes |

| network | HBO |

| picture format | 4:3 480i (Seasons 1–6)16:9 1080i (Season 7–) |

| first aired | |

| last aired | present |

| related | Seinfeld |

| website | http://www.hbo.com/curb-your-enthusiasm/ }} |

Curb Your Enthusiasm is an American comedy television series produced and broadcast by HBO, which started its first season in 2000. The eighth season, consisting of ten episodes, premiered on July 10, 2011. The series was created by Seinfeld co-creator Larry David, who stars as a fictionalized version of himself. The series follows David in his life as a semi-retired television writer and producer in Los Angeles and later New York City. Also starring is Cheryl Hines as David's wife Cheryl, Jeff Garlin as David's manager Jeff, and Susie Essman as Jeff's wife Susie. Curb often features guest stars, and some of these appearances are by celebrities playing themselves.

The plots and subplots of the episodes are established in an outline written by David and the dialogue is largely improvised by the actors themselves. Much like Seinfeld, the subject matter in Curb Your Enthusiasm often involves the minutiae of daily life, and plots often revolve around Larry David's many faux pas, and his problems with certain social conventions and expectations, as well as his annoyance with other people's behavior. The character has a hard time letting such annoyances go unexpressed, which leads him often into awkward situations.

The series was developed from a 1999 one-hour special titled Larry David: Curb Your Enthusiasm, which David and HBO originally envisioned as a one-time project. This special was shot as a mockumentary, where the characters were aware of the presence of cameras and a crew. The series itself is not a mock documentary, but it is shot in a somewhat similar cinéma vérité-like style.

Curb Your Enthusiasm has been nominated for 34 Primetime Emmy Awards, and Robert B. Weide received an Emmy for Outstanding Directing for a Comedy Series, for the episode "Krazee Eyez Killa." The show won the 2002 Golden Globe Award for Best Television Series – Musical or Comedy.

Concept

The series stars Larry David as an extreme fictionalized version of himself. Similar to the real-life David, the character is well-known in the entertainment industry as the co-creator and main co-writer of the highly successful sitcom Seinfeld. Throughout most of the series, the Larry David character is living a married life in Los Angeles with his wife Cheryl (played by Cheryl Hines), without children. David's main confidant on the show is his manager, Jeff Greene (played by Curb executive producer Jeff Garlin), who has a temperamental wife Susie (Susie Essman). A large portion of the show's many guest stars are various celebrities and public figures, such as actors, comedians, and sportspeople, who play themselves. These include David's long-time friend Richard Lewis, as well as Ted Danson and his wife Mary Steenburgen, who all have recurring roles as fictionalized versions of themselves.The show is set and filmed in various affluent Westside communities of (and occasionally downtown) Los Angeles, California, as well as the adjacent incorporated cities of Beverly Hills, Culver City and Santa Monica. Some of the episodes (especially in the eighth season) also feature New York City, Larry David's hometown.

Although David maintains an office, he leads a semi-retired life in the series, and is rarely shown working regularly, other than in season four, which centered on his being cast as the lead in the Mel Brooks play The Producers, and in season seven, writing a Seinfeld reunion show. Most of the series revolves around Larry's interactions with his friends and acquaintances, with Larry often at odds with the other characters (usually to Larry's detriment). Despite this, the characters do not seem to harbor ill feelings toward each other for any extended period and the cast has stayed stable throughout the show.

David has explained the meaning of the show's title in TV interviews: It reflects his perception that many people seem to live their lives projecting false enthusiasm, which he believes is used to imply that "they are better than you." This conflicts with his style, which is very droll and dry. The title also urges the audience not to expect too much from the show; at the time of the premiere, David wanted to lower expectations after the phenomenal success of Seinfeld.

Characters

Main cast

Larry David (Larry David) – Candid, neurotic, but generally disposed to pursue what he perceives to be the right course, Larry often finds himself in awkward situations that arise as a result of his obstinate belief in his own ethical principles and codes of conduct, which he is nevertheless prepared to bend when it suits him. He usually has good intentions but often finds himself a victim of circumstance and social convention, as many of the people around him are also self-centered and stubborn; the character's unintentional tactlessness has resulted in the term "Larry David Moment" entering the American pop culture lexicon as a slang term for an inadvertently created socially awkward situation. He often centers on petty details, to the extent of aggravating everyone around him just to prove an insignificant point. The real life Larry David has commented that although he secretly wishes to be more like his fictionalized version on the series, he could never be that way because he is a lot more cautious when it comes to social tension. Larry's trademark behaviors are his probing stare when he doesn't think somebody is telling the truth, fondly saying something is "prett-ay, prett-ay, prett-ay, pretty good" and, when caught up short in a moment of poor or contrary behavior, quizzically and mock-innocently inquiring, often of his wife, Cheryl, or of a close friend, "No good?"Jeff Greene (Jeff Garlin) – One of Larry's closest friends, Jeff is his sympathetic manager whose marital problems and adulterous misadventures entangle Larry in embarrassing situations. Jeff often helps Larry with his problems, but that usually leads to Jeff getting entangled in the mess. Jeff and his wife, Susie (Susie Essman), have a daughter named Sammi (Ashly Holloway). While they ultimately love each other, his wife constantly criticizes him on his decisions and weight, while his daughter at times is neutral about her love for her father. Jeff Garlin stated that he truly does not empathize with his character at all and described him as a "pretty evil guy" who has "no morals, no scruples".

Recurring roles

Among the show's many recurring roles, Richard Lewis and Ted Danson play versions of themselves as old friends of Larry's with whom he frequently butts heads. Shelley Berman plays Larry's father, Nat David. Bob Einstein frequently appears as Marty Funkhouser, another of Larry's oldest friends. Beginning with season six, J. B. Smoove appears as Leon Black and in seasons six and seven, Vivica A. Fox appears as Loretta Black, members of a family of hurricane evacuees who stay in Larry's house.

Notable guest appearances

Celebrities, including actors, comedians, authors, musicians and athletes, often make guest appearances on the show, with a large portion of them playing themselves, or fictional versions thereof. Some of the guest stars who have appeared as themselves include Mel Brooks, Michael York, Martin Scorsese, Ben Stiller, David Schwimmer, Shaquille O'Neal, Rosie O'Donnell, Ricky Gervais, Michael J. Fox, and the main cast of Seinfeld. Notable people who filled in fictional roles include Bea Arthur, Dustin Hoffman, Sacha Baron Cohen, Stephen Colbert, and Steve Coogan.

Plots and episodes