- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2012 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (325/330–after 391) was a fourth-century Roman historian. His is the penultimate major historical account written during Antiquity (the last was written by Procopius). His work chronicled in Latin the history of Rome from 96 to 378, although only the sections covering the period 353–378 are extant.

http://wn.com/Ammianus_Marcellinus -

Arulenus Rusticus

Quintus Junius Arulenus Rusticus, (c. 35-93 AD), is more usually called Arulenus Rusticus, but sometimes also Junius Rusticus. He was a friend and follower of Thrasea Paetus, and, like the latter, an ardent admirer of Stoic philosophy. He was Tribune of the plebs in AD 66, in which year Thrasea was condemned to death by the Roman Senate; and he would have placed his veto upon the senatus consultum, had not Thrasea prevented him, as he would only have brought certain destruction upon himself without saving the life of the defendant. He was Praetor in the civil wars after the death of Nero, (69 AD), when as one of the senate's ambassadors to the Flavian armies he was wounded by the soldiers of Petilius Cerialis. He attained a very late consulship in AD 92 under Domitian, but in the following year was condemned to death because of his panegyric on Thrasea. Suetonius attributes to him a panegyric upon Helvidius Priscus; but the latter work was composed by Herennius Senecio, as we learn both from Tacitus and Pliny.

http://wn.com/Arulenus_Rusticus -

Augustus

:For other uses of Octavius, see Octavius (disambiguation). For other uses of Octavian, see Octavian (disambiguation). For other uses of Augustus, see Augustus (disambiguation).

http://wn.com/Augustus -

Augustus Caesar

http://wn.com/Augustus_Caesar -

Calgacus

According to Tacitus, Calgacus (sometimes Calgacos or Galgacus) was a chieftain of the Caledonian Confederacy who fought the Roman army of Gnaeus Julius Agricola at the Battle of Mons Graupius in northern Scotland in AD 83 or 84. His name can be as interpreted as Celtic *calg-ac-os, "possessing a blade" or "possessing a penis".

http://wn.com/Calgacus -

Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August AD 12 – 24 January AD 41), commonly known as Caligula and sometimes Gaius, was Roman Emperor from 37 to 41. Caligula was a member of the house of rulers conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Caligula's father Germanicus, the nephew and adopted son of emperor Tiberius, was a very successful general and one of Rome's most beloved public figures. The young Gaius earned the nickname Caligula (the diminutive form of caliga meaning "little soldier's boot") from his father's soldiers while accompanying him during his campaigns in Germania. When Germanicus died at Antioch in 19 AD, his mother Agrippina the Elder returned to Rome with her six children where she became entangled in an increasingly bitter feud with Tiberius. This conflict eventually led to the destruction of her family, with Caligula as the sole male survivor. Unscathed by the deadly intrigues, Caligula accepted the invitation to join the emperor on the island of Capri in 31, where Tiberius himself had withdrawn five years earlier. At the death of Tiberius in 37, Caligula succeeded his great-uncle and adoptive grandfather.

http://wn.com/Caligula -

Caria

| class="toccolours" border="1" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="2" style="float: right; margin: 0 0 1em 1em; width: 250px; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;"

http://wn.com/Caria -

Celts

The Celts ( or , see names of the Celts) were a diverse group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Roman-era Europe who spoke Celtic languages.

http://wn.com/Celts -

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero (; Classical Latin: ; January 3, 106 BC – December 7, 43 BC; sometimes anglicized as "Tully"), was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

http://wn.com/Cicero -

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), born Tiberius Claudius Drusus, then Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus until his accession, was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54 AD. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul, and was the first emperor to be born outside Italy. Afflicted with a limp and slight deafness due to sickness at a young age, his family ostracized him and excluded him from public office until his consulship with his nephew Caligula in 37 AD. Claudius' infirmity probably saved him from the fate of many other nobles during the purges of Tiberius' and Caligula's reigns; potential enemies did not see him as a serious threat. His survival led to his being declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard after Caligula's assassination, at which point he was the last adult male of his family.

http://wn.com/Claudius -

Cremutius Cordus

http://wn.com/Cremutius_Cordus -

Domitian

Titus Flavius Domitianus (24 October 51 – 18 September 96), commonly known as Domitian, was Roman Emperor from 81 to 96. Domitian was the third and last emperor of the Flavian dynasty.

http://wn.com/Domitian -

Fenni

The Fenni were an ancient people of northeastern Europe first described by Cornelius Tacitus in Germania in AD 97.

http://wn.com/Fenni -

Germania

Germania was the Latin term for a geographical area of land on the east bank of the Rhine (inner Germania), which included regions of Sarmatia as well as an area under Roman control on the west bank of the Rhine. The name came into use after Julius Caesar adopted it from a Gallic term for the peoples east of the Rhine that probably meant "neighbour".

http://wn.com/Germania -

Germanic tribe

http://wn.com/Germanic_tribe -

Hadrian

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (24 January 76 – 10 July 138), commonly known as Hadrian and after his apotheosis Divus Hadrianus, was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best-known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman territory in Britain. In Rome, he built the Pantheon and the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian is also a notable Stoic and Epicurean philosopher. A member of the gens Aelia, Hadrian was the third of the so-called Five Good Emperors.

http://wn.com/Hadrian -

Herodotus

Herodotus (Greek: Hēródotos) was an ancient Greek historian who lived in the 5th century BC ( – ). He was born in Caria, Halicarnassus (modern day Bodrum, Turkey). He is regarded as the "Father of History" in Western culture. He was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a well-constructed and vivid narrative. He is exclusively known for writing The Histories, a record of his "inquiry" (or historía, a word that passed into Latin and took on its modern meaning of history) into the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars which occurred in 490 and 480-479 BC—especially since he includes a narrative account of that period, which would otherwise be poorly documented; and many long digressions concerning the various places and people he encountered during wide-ranging travels around the lands of the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Although some of his stories were not completely accurate, he claimed that he was reporting only what had been told to him.

http://wn.com/Herodotus -

Jerome

St Jerome (c. 347 – 30 September 420) (formerly Saint Hierom) (; ; ) was an Illyrian Christian priest and apologist. He was the son of Eusebius, of the city of Stridon, which was on the border of Dalmatia and Pannonia. He is best known for his translation of the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate), and his list of writings is extensive.

http://wn.com/Jerome -

Jew

http://wn.com/Jew -

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. He played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

http://wn.com/Julius_Caesar -

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (in Latin: M·ANTONIVS·M·F·M·N) (January 14, 83 BC – August 1, 30 BC), known in English as Mark (or Marc) Antony (or Anthony), was a Roman politician and general. He was an important supporter and the loyal friend of Gaius Julius Caesar as a military commander and administrator, despite his blood ties, through his mother Julia, to the branch of Caesars opposed to the Marians and murdered by them. After Caesar's assassination, Antony formed an official political alliance with Octavian (Augustus) and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, known to historians today as the Second Triumvirate.

http://wn.com/Mark_Antony -

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (15 December 37 – 9 June 68), born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, and commonly known as Nero, was Roman Emperor from 54 to 68. He was the last emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great-uncle Claudius to become his heir and successor. He succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius' death.

http://wn.com/Nero -

Nerva

Marcus Cocceius Nerva (8 November 30 – 25 January 98), commonly known as Nerva, was Roman Emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor at the age of sixty-five, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the rulers of the Flavian dynasty. Under Nero, he was a member of the imperial entourage and played a vital part in exposing the Pisonian conspiracy of 65. Later, as a loyalist to the Flavians, he attained consulships in 71 and 90 during the reigns of Vespasian and Domitian respectively.

http://wn.com/Nerva -

Octavia Minor

http://wn.com/Octavia_Minor -

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (23 AD – August 25, 79), better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian. Spending most of his spare time studying, writing or investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field, he wrote an encyclopedic work, Naturalis Historia, which became a model for all such works written subsequently. Pliny the Younger, his nephew, wrote of him in a letter to the historian Tacitus:

http://wn.com/Pliny_the_Elder -

Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo (61 AD – ca. 112 AD), better known as Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and educate him and they were both witnesses to the eruption of Vesuvius on 24 August 79 AD.

http://wn.com/Pliny_the_Younger -

Plutarch

Plutarch, born Plutarchos (Greek: Πλούταρχος) then, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus (Μέστριος Πλούταρχος), c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia. He was born to a prominent family in Chaeronea, Boeotia, a town about twenty miles east of Delphi.

http://wn.com/Plutarch -

Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (ca. 35 – ca. 100) was a Roman rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilian, although the alternate spellings of Quintillian and Quinctilian are occasionally seen, the latter in older texts.

http://wn.com/Quintilian -

Revilo P. Oliver

Revilo Pendleton Oliver (July 7, 1908 — August 20, 1994) was an American professor of Classical philology, Spanish, and Italian at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who wrote and polemicized extensively for white nationalist causes.

http://wn.com/Revilo_P_Oliver -

Robert Van Voorst

http://wn.com/Robert_Van_Voorst -

Roman Emperor

The Roman Emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period (starting at about 27 BC). The Romans had no single term for the office: Latin titles such as imperator (from which English emperor ultimately derives), augustus, caesar and princeps were all associated with it. In practice, the emperor was supreme ruler of Rome and supreme commander of the Roman legions.

http://wn.com/Roman_Emperor -

Ronald Syme

Sir Ronald Syme, OM, FBA (11 March 1903 – 4 September 1989) was a New Zealand-born historian and classicist. Long associated with Oxford University, he is considered one of the twentieth century's greatest historians of ancient Rome.

http://wn.com/Ronald_Syme -

Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Seianus (20 BC – October 18, AD 31), commonly known as Sejanus, was an ambitious soldier, friend and confidant of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. An equestrian by birth, Sejanus rose to power as prefect of the Roman imperial bodyguard, known as the Praetorian Guard, of which he was commander from AD 14 until his death in 31.

http://wn.com/Sejanus -

Sidonius Apollinaris

:For the Franco-Irish saint, see Sidonius of Saint-Saëns.

http://wn.com/Sidonius_Apollinaris -

Tacitus on Christ

Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius Tacitus (AD 56 – AD 117) was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. His writings cover the history of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus in AD 14 to the death of emperor Domitian in AD 96.

http://wn.com/Tacitus_on_Christ -

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (November 16, 42 BC – March 16, AD 37), born Tiberius Claudius Nero, was Roman Emperor from 14 AD to 37 AD. Tiberius was by birth a Claudian, son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla. His mother divorced his father and was remarried to Augustus in 39 BC, making him a step-son of Octavian. Tiberius would later marry Augustus' daughter Julia the Elder (from his marriage to Scribonia) and even later be adopted by Augustus, by which act he officially became a Julian, bearing the name Tiberius Julius Caesar. The subsequent emperors after Tiberius would continue this blended dynasty of both families for the next forty years; historians have named it the Julio-Claudian dynasty. In relations to the other emperors of this dynasty, Tiberius was the stepson of Augustus, great-uncle of Caligula, paternal uncle of Claudius, and great-great uncle of Nero.

http://wn.com/Tiberius -

Titus

:For the personal name, see Titus (praenomen). For other uses, see Titus (disambiguation).

http://wn.com/Titus -

Trajan

Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus (18 September 53 – 9 August 117), commonly known as Trajan, was Roman Emperor from 98 to 117. Born into a non-patrician family in the province of Hispania Baetica, Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperor Domitian. Serving as a general in the Roman army along the German frontier, Trajan successfully put down the revolt of Antonius Saturninus in 89. In September 96, Domitian was succeeded by Marcus Cocceius Nerva, an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of the Praetorian Guard compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on 27 January 98, and was succeeded by his adopted son without incident.

http://wn.com/Trajan -

Vespasian

Titus Flavius Vespasianus , commonly known as Vespasian (17 November 9 – 23 June 79), was Roman Emperor from 69 C.E to 79 C.E. Vespasian was the founder of the Flavian dynasty which ruled the empire for a quarter century. Vespasian was descended from a family of equestrians which rose into the senatorial rank under the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Although he attained the standard succession of public offices, holding the consulship in 51 C.E, Vespasian became more reputed as a successful military commander, participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43, and subjugating Judaea during the Jewish rebellion of 66 C.E. While Vespasian was preparing to besiege the city of Jerusalem during the latter campaign, emperor Nero committed suicide, plunging the empire into a year of civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors. After the emperors Galba and Otho perished in quick succession, Vitellius became emperor in April 69 C.E. In response, the armies in Egypt and Judaea declared Vespasian emperor on July 1. In his bid for imperial power, Vespasian joined forces with Mucianus, the governor of Syria, and Primus, a general in Pannonia. Primus and Mucianus led the Flavian forces against Vitellius, while Vespasian gained control of Egypt. On 20 December, Vitellius was defeated, and the following day Vespasian was declared emperor by the Roman Senate.

http://wn.com/Vespasian

-

Anatolia

Anatolia (, from Greek '; also Asia Minor, from , ') is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey. The region is bounded by the Black Sea to the north, Georgia to the northeast, the Armenian Highland to the east, Mesopotamia to the southeast, the Mediterranean Sea to the south and the Aegean Sea to the west. Anatolia has been home to many civilizations throughout history, such as the Hittites, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Greeks, Assyrians, Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Anatolian Seljuks and Ottomans. As a result, Anatolia is one of the archeologically richest areas in the world.

http://wn.com/Anatolia -

Italy

Italy (; ), officially the Italian Republic (), is a country located in south-central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia along the Alps. To the south it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Sardinia — the two largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea — and many other smaller islands. The independent states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy, whilst Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland. The territory of Italy covers some and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With 60.4 million inhabitants, it is the sixth most populous country in Europe, and the twenty-third most populous in the world.

http://wn.com/Italy -

Monte Cassino

:For information about the World War II battle, see the Battle of Monte Cassino.

http://wn.com/Monte_Cassino -

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, in Southwest Asia, is an extension of the Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula. Historically and commonly known as the Persian Gulf, this body of water is also controversially referred to as the Arabian Gulf (by the Arab nations on the Arab side of the gulf) or simply The Gulf by most Arab states, and Gulf of Basra by Turkey, although none of the latter three terms is recognized internationally.

http://wn.com/Persian_Gulf -

Rome

Rome (; , ; ) is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . In 2006 the population of the metropolitan area was estimated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to have a population of 3.7 million.

http://wn.com/Rome

- acta senatus

- Agricola

- Agricola (book)

- Ammianus Marcellinus

- Anatolia

- Annals (Tacitus)

- Antonia

- apathy

- Aristocracy (class)

- Arulenus Rusticus

- Aufidius Bassus

- Augustan History

- Augustus

- Augustus Caesar

- author

- Baltic Sea

- Belgica

- biography

- Book of Zechariah

- Britannia

- Britons (historic)

- Calgacus

- Caligula

- Canonical gospels

- Caria

- Celts

- Christ

- Christian

- Christians

- Cicero

- Classical Latin

- classical literature

- Claudius

- Cluvius Rufus

- cognomen

- Corvey Abbey

- Cremutius Cordus

- cursus honorum

- decadence

- dialogue

- dissimulation

- Domitian

- Empoli

- epigram

- equestrian (Roman)

- ethnography

- Fabius Iustus

- Fabius Rusticus

- Fenni

- figure of speech

- Flavian dynasty

- free speech

- freedman

- Gallia Narbonensis

- Gallo-Roman

- Germania

- Germania (book)

- Germanic tribe

- Giuseppe Toffanin

- Great Jewish Revolt

- Hadrian

- Harold Mattingly

- Helvidius

- Herennius Senecio

- Herodotus

- Hispania

- historian

- Histories (Tacitus)

- History

- hunting

- hypocrisy

- Italy

- Jerome

- Jew

- Julia Agricola

- Julio-Claudian

- Julius Caesar

- Lacuna (manuscripts)

- Latin

- Latin language

- latus clavus

- law

- Machiavellian

- Manricus

- Marius Priscus

- Mark Antony

- Monte Cassino

- Mylasa

- Nero

- Nerva

- novus homo

- Octavia Minor

- orator

- oratory

- Persian Gulf

- Pliny the Elder

- Pliny the Younger

- Plutarch

- Polemius

- political corruption

- politics

- praenomen

- praetor

- primary source

- proconsul

- Promagistrate

- proscription

- Psyche (psychology)

- quaestor

- Quintilian

- realpolitik

- Red Sea

- Republic (Plato)

- republicanism

- Revilo P. Oliver

- rhetoric

- Robert Van Voorst

- Roman Britain

- Roman consul

- Roman Emperor

- Roman Empire

- Roman governor

- Roman legion

- Roman Republic

- Roman Senate

- Rome

- Ronald Syme

- Sallust

- Secular games

- Sejanus

- Sibylline Books

- Sidonius Apollinaris

- social class

- Stoicism

- suffect consul

- Tacitean studies

- Tacitus on Christ

- terminus post quem

- Tiberius

- Titus

- Trajan

- tyranny

- Vespasian

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:18

- Published: 04 Jan 2012

- Uploaded: 24 Jan 2012

- Author: InTeamFunwetrust

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:06

- Published: 03 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 15 Nov 2011

- Author: ForBibletruth

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:00

- Published: 07 Nov 2009

- Uploaded: 22 Sep 2011

- Author: Tacitus2COIG

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:11

- Published: 06 Jan 2009

- Uploaded: 06 Feb 2012

- Author: ForBibletruth

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:03

- Published: 08 Jan 2009

- Uploaded: 18 Oct 2011

- Author: ForBibletruth

![[12] The Tacitus - Kane's Wrath Cinematics [12] The Tacitus - Kane's Wrath Cinematics](http://web.archive.org./web/20120303075942im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/aMUh-wCimcs/0.jpg)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 0:59

- Published: 26 Mar 2008

- Uploaded: 02 Jan 2012

- Author: fieryspirit1

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:46

- Published: 01 Apr 2009

- Uploaded: 21 Oct 2011

- Author: jackospade0418

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:36

- Published: 04 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 08 Jan 2012

- Author: ForBibletruth

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:56

- Published: 03 Apr 2009

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: jackospade0418

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:31

- Published: 02 Jan 2012

- Uploaded: 12 Feb 2012

- Author: FrackingRebels

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:49

- Published: 14 Oct 2011

- Uploaded: 15 Oct 2011

- Author: adrianmurdoch

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:04

- Published: 03 Apr 2009

- Uploaded: 21 Oct 2011

- Author: jackospade0418

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:14

- Published: 08 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 05 Mar 2011

- Author: mastercommander15

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:23

- Published: 20 Dec 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Feb 2012

- Author: FrackingRebels

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:21

- Published: 01 Apr 2009

- Uploaded: 21 Oct 2011

- Author: jackospade0418

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:44

- Published: 21 Jan 2012

- Uploaded: 11 Feb 2012

- Author: FrackingRebels

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:41

- Published: 10 Jan 2012

- Uploaded: 07 Feb 2012

- Author: FrackingRebels

- acta senatus

- Agricola

- Agricola (book)

- Ammianus Marcellinus

- Anatolia

- Annals (Tacitus)

- Antonia

- apathy

- Aristocracy (class)

- Arulenus Rusticus

- Aufidius Bassus

- Augustan History

- Augustus

- Augustus Caesar

- author

- Baltic Sea

- Belgica

- biography

- Book of Zechariah

- Britannia

- Britons (historic)

- Calgacus

- Caligula

- Canonical gospels

- Caria

- Celts

- Christ

- Christian

- Christians

- Cicero

- Classical Latin

- classical literature

- Claudius

- Cluvius Rufus

- cognomen

- Corvey Abbey

- Cremutius Cordus

- cursus honorum

- decadence

- dialogue

- dissimulation

- Domitian

- Empoli

- epigram

- equestrian (Roman)

- ethnography

- Fabius Iustus

- Fabius Rusticus

- Fenni

- figure of speech

- Flavian dynasty

- free speech

- freedman

- Gallia Narbonensis

- Gallo-Roman

- Germania

- Germania (book)

- Germanic tribe

- Giuseppe Toffanin

| Coordinates | 41°52′55″N87°37′40″N |

|---|---|

| Name | Tacitus |

| Birthdate | ca. AD 56 |

| Deathdate | ca. 117 |

| Occupation | Senator, consul, governor, historian |

| Genre | History |

| Subject | History, biography, oratory |

| Movement | Silver Age of Latin |

| Signature | }} |

Other works by Tacitus discuss oratory (in dialogue format, see ''Dialogus de oratoribus''), Germania (in ''De origine et situ Germanorum''), and biographical notes about his father-in-law Agricola, primarily during his campaign in Britannia (see ''De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae'').

Tacitus was an author writing in the latter part of the Silver Age of Latin literature. His work is distinguished by a boldness and sharpness of wit, and a compact and sometimes unconventional use of Latin.

Life

While Tacitus' works contain much information about his world, details regarding his personal life are scarce. What little is known comes from scattered hints throughout his work, the letters of his friend and admirer Pliny the Younger, an inscription found at Mylasa in Caria, and educated guesswork.Tacitus was born in 56 or 57 to an equestrian family; like many Latin authors of the Golden and Silver Ages, he was from the provinces, probably either northern Italy, Gallia Narbonensis, or Hispania. The exact place and date of his birth are not known, while his praenomen (first name) is similarly a mystery; in the letters of Sidonius Apollinaris his name is ''Gaius'', but in the major surviving manuscript of his work his name is given as ''Publius''. (One scholar's suggestion of ''Sextus'' has gained no traction.)

Family and early life

The older aristocratic families were largely destroyed during the proscriptions at the end of the Republic, and Tacitus is clear that he owes his rank to the Flavian emperors (''Hist.'' 1.1). The theory that he descended from a freedman finds no support apart from his statement, in an invented speech, that many senators and knights were descended from freedmen (''Ann.'' 13.27), and is dismissed by prominent historians.His father may have been the Cornelius Tacitus who was procurator of Belgica and Germania; Pliny the Elder mentions that Cornelius had a son who grew and aged rapidly (N.H. 7.76), and implies an early death. If Cornelius was Tacitus' father and since there is no mention of Tacitus suffering such a condition in the surviving record, it would likely refer to a brother instead. This connection, and the friendship between the younger Pliny and Tacitus, led many scholars to the conclusion that the two families were of similar class, means, and background: equestrians, of significant wealth, and from provincial families.

The province of his birth is unknown and has been variously conjectured as Gallia Belgica, Gallia Narbonensis, or even northern Italy. His marriage to the daughter of the Narbonensian senator Gnaeus Julius Agricola may indicate that he, too, came from Gallia Narbonensis. Tacitus' dedication to Fabius Iustus in the ''Dialogus'' may indicate a connection with Spain, while his friendship with Pliny indicates northern Italy. None of this evidence is conclusive. No evidence exists that Pliny's friends from northern Italy knew Tacitus, nor do Pliny's letters ever hint that the two men had a common background. Indeed, the strongest piece of evidence is in Pliny Book 9, Letter 23, which reports that when Tacitus was asked if he were Italian or provincial, upon giving an unclear answer, was further asked if he were Tacitus or Pliny. Since Pliny was from Italy, some historians infer that Tacitus was from the provinces, possibly Gallia Narbonensis.

His ancestry, his skill in oratory, and his sympathetic depiction of barbarians who resisted Roman rule (e.g., ''Ann.'' 2.9), have led some to suggest that he was a Celt; the Celts had occupied Gaul before the Romans, were famous for their skill in oratory, and had been subjugated by Rome.

Public life, marriage, and literary career

As a young man, Tacitus studied rhetoric in Rome to prepare for a career in law and politics; like Pliny, he may have studied under Quintilian. In 77 or 78 he married Julia Agricola, daughter of the famous general Agricola; little is known of their home life, save that Tacitus loved hunting and the outdoors. He started his career (probably the ''latus clavus'', mark of the senator) under Vespasian, but it was in 81 or 82, under Titus, that he entered political life, as quaestor. He advanced steadily through the ''cursus honorum'', becoming praetor in 88 and a quindecimvir, a member of the priest college in charge of the Sibylline Books and the Secular games. He gained acclaim as a lawyer and an orator; his skill in public speaking gave a marked irony to his cognomen: ''Tacitus'' ("silent").He served in the provinces from ca. 89 to ca. 93 either in command of a legion or in a civilian post. His person and property survived Domitian's reign of terror (81–96), but the experience left him jaded and grim (perhaps ashamed at his own complicity), and gave him the hatred of tyranny evident in his works. The ''Agricola'', chs. 44–45, is illustrative:

Agricola was spared those later years during which Domitian, leaving now no interval or breathing space of time, but, as it were, with one continuous blow, drained the life-blood of the Commonwealth... It was not long before our hands dragged Helvidius to prison, before we gazed on the dying looks of Manricus and Rusticus, before we were steeped in Senecio's innocent blood. Even Nero turned his eyes away, and did not gaze upon the atrocities which he ordered; with Domitian it was the chief part of our miseries to see and to be seen, to know that our sighs were being recorded...

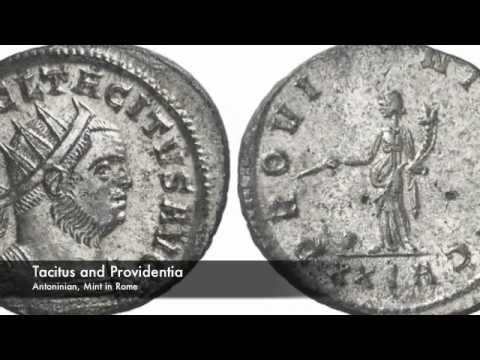

From his seat in the Senate he became suffect consul in 97 during the reign of Nerva, being the first of his family to do so. During his tenure he reached the height of his fame as an orator when he delivered the funeral oration for the famous veteran soldier Lucius Verginius Rufus.

In the following year he wrote and published the ''Agricola'' and ''Germania'', announcing the beginnings of the literary endeavors that would occupy him until his death. Afterwards he absented himself from public life, but returned during Trajan's reign. In 100, he, along with his friend Pliny the Younger, prosecuted Marius Priscus (proconsul of Africa) for corruption. Priscus was found guilty and sent into exile; Pliny wrote a few days later that Tacitus had spoken "with all the majesty which characterizes his usual style of oratory".

A lengthy absence from politics and law followed while he wrote his two major works: the ''Histories'' and the ''Annals''. In 112 or 113 he held the highest civilian governorship, that of the Roman province of ''Asia'' in Western Anatolia, recorded in the inscription found at Mylasa mentioned above. A passage in the ''Annals'' fixes 116 as the ''terminus post quem'' of his death, which may have been as late as 125 or even 130. At all events it seems certain that he survived both Pliny and Trajan. It is unknown whether he had any children, though the ''Augustan History'' reports that the emperor Marcus Claudius Tacitus claimed him for an ancestor and provided for the preservation of his works—but like so much of the ''Augustan History'', this story may be fraudulent.

Works

Five works ascribed to Tacitus have survived (albeit with some lacunae), the largest of which are the ''Annals'' and the ''Histories''. The dates are approximate:

Major works

The ''Annals'' and the ''Histories'', originally published separately, were meant to form a single edition of thirty books. Although Tacitus wrote the ''Histories'' before the ''Annals'', the events in the ''Annals'' precede the ''Histories''; together they form a continuous narrative from the death of Augustus (14) to the death of Domitian (96). Though most has been lost, what remains is an invaluable record of the era. When it is remembered that the first half of the Annals survived in a single copy of a manuscript from Corvey Abbey, and the second half from a single copy of a manuscript from Monte Cassino, it is remarkable that they survived at all.

The ''Histories''

In an early chapter of the ''Agricola'', Tacitus said he wished to speak about the years of Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan. In the ''Histories'' the scope has changed; Tacitus says that he will deal with the age of Nerva and Trajan at a later time. Instead, he will cover the period from the civil wars of the Year of Four Emperors and end with the despotism of the Flavians. Only the first four books and twenty-six chapters of the fifth book survive, covering the year 69 and the first part of 70. The work is believed to have continued up to the death of Domitian on September 18, 96. The fifth book contains—as a prelude to the account of Titus's suppression of the Great Jewish Revolt—a short ethnographic survey of the ancient Jews and is an invaluable record of the educated Romans' attitude towards that people.

The ''Annals''

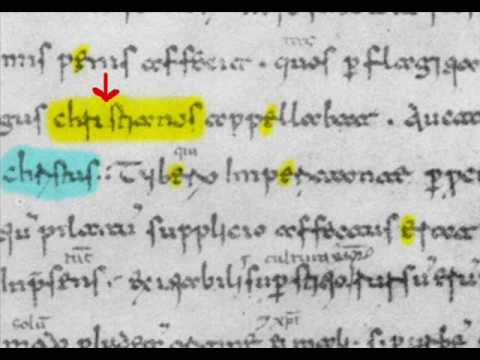

The ''Annals'' was Tacitus' final work, covering the period from the death of Augustus Caesar in 14 AD. He wrote at least sixteen books, but books 7–10 and parts of books 5, 6, 11 and 16 are missing. Book 6 ends with the death of Tiberius and books 7–12 presumably covered the reigns of Caligula and Claudius. The remaining books cover the reign of Nero, perhaps until his death in June 68 or until the end of that year, to connect with the ''Histories''. The second half of book 16 is missing (ending with the events of 66). We do not know whether Tacitus completed the work or whether he finished the other works that he had planned to write; he died before he could complete his planned histories of Nerva and Trajan, and no record survives of the work on Augustus Caesar and the beginnings of the Empire with which he had planned to finish his work. The ''Annals'' is also among the first-known rare secular-historic records to mention Christ (see Tacitus on Christ), which Tacitus does in connection with Nero's persecution of the Christians.

Tacitus on Christ

In his ''Annals'', in book 15, chapter 44, written ca. 116 A.D., there is a passage which refers to Christ, to Pontius Pilate, and to a mass execution of the Christians after a six-day fire that burned much of Rome in July of 64 A.D. by Nero. This narration has long attracted scholarly interest and contains a rare non-Christian reference to the origin of Christianity, the execution of Christ described in the Canonical gospels, and the persecution of Christians in 1st-century Rome. Although this passage was edited some 52 years after the events, almost all scholars consider the narration authentic.

Minor works

Tacitus wrote three minor works on various subjects: the ''Agricola'', a biography of his father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola; the ''Germania'', a monograph on the lands and tribes of barbarian Germania; and the ''Dialogus'', a dialogue on the art of rhetoric.

''Germania''

The ''Germania'' (Latin title: ''De Origine et situ Germanorum'') is an ethnographic work on the diverse set of people Tacitus believed to be Germanic tribes outside the Roman Empire. Ethnography already had a long and distinguished heritage in classical literature, and the ''Germania'' fits squarely within the tradition established by authors from Herodotus to Julius Caesar. The book begins (chapters 1–27) with a description of the lands, laws, and customs of the tribes. Later chapters focus on descriptions of individual tribes, beginning with those dwelling closest to Roman lands and ending on the uttermost shores of the Baltic Sea, with a description of the Fenni and the unknown tribes beyond them. Tacitus had written a similar, albeit shorter, piece in his ''Agricola'' (chapters 10–13).

''Agricola'' (''De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae'')

The ''Agricola'' (written ca. 98) recounts the life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, an eminent Roman general and Tacitus' father-in-law; it also covers, briefly, the geography and ethnography of ancient Britain. As in the ''Germania'', Tacitus favorably contrasts the liberty of the native Britons with the corruption and tyranny of the Empire; the book also contains eloquent and vicious polemics against the rapacity and greed of Rome, in one of which Tacitus says is from a speech by Calgacus and ends with ''Auferre trucidare rapere falsis nominibus imperium, atque ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant.'' (To ravage, to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make a desert, they call it peace. — Oxford Revised Translation).

''Dialogus''

There is uncertainty about when Tacitus wrote ''Dialogus de oratoribus'' , but it was probably after the ''Agricola'' and the ''Germania''. Many characteristics set it apart from the other works of Tacitus, so that its authenticity has been questioned, although it is still grouped with the ''Agricola'' and the ''Germania'' in the manuscript tradition. The way of speaking in the ''Dialogus'' seems closer to Cicero's proceedings, refined but not prolix, which inspired the teaching of Quintilian; it lacks the incongruities that are typical of Tacitus' major historical works. It may have been written when Tacitus was young; its dedication to Fabius Iustus would thus give the date of publication, but not the date of writing. More probably, the unusually classical style may be explained by the fact that the ''Dialogus'' is a work dealing with rhetoric. For works in the ''rhetoric'' genre, the structure, the language, and the style of Cicero were the usual models.

The sources of Tacitus

Tacitus used the official sources of the Roman state: the ''acta senatus'' (the minutes of the session of the Senate) and the ''acta diurna populi Romani'' (a collection of the acts of the government and news of the court and capital). He read collections of emperors' speeches, such as Tiberius and Claudius. Generally, Tacitus was a scrupulous historian who paid careful attention to his historical works. The minor inaccuracies in the ''Annals'' may be due to Tacitus dying before finishing (and therefore proofreading) his work. He used a variety of historical and literary sources; he used them freely and he chose from sources of varied opinions.Tacitus cites some of his sources directly, among them Cluvius Rufus, Fabius Rusticus and Pliny the Elder, who had written ''Bella Germaniae'' and a historical work which was the continuation of that of Aufidius Bassus. Tacitus used some collections of letters (''epistolarium'') and various notes. He also took information from ''exitus illustrium virorum''. These were a collection of books by those who were antithetical to the emperors. They tell of the sacrifice of the martyr to freedom, especially the men who committed suicide, following the theory of the Stoics. While he placed no value on the Stoic theory of suicide, Tacitus used accounts of famous suicides to give a dramatic tone to his stories. These suicides seemed, to him, ostentatious and politically useless; however, he gives prominence to the speeches of some of those about to commit suicide, for example Cremutius Cordus' speech in ''Ann.'' IV, 34-35.

Literary style

Tacitus's writings are known for their dense, profound prose that seldom glosses the facts, standing in contrast to the placable style of some of his contemporaries, such as Plutarch. Describing a near-defeat of the Roman army in ''Ann.'' I, 63 he does gloss the end of the hostilities, but does so by brevity of description rather than by embellishment.In most of his writings, he keeps to a chronological narrative order, only seldom outlining the bigger picture, and leaves the reader to construct that picture for himself. Nonetheless, where he does paint in broad strokes—for example, in the opening paragraphs of the ''Annals'', summarizing the situation at the end of the reign of Augustus—he uses a few condensed phrases to take the reader to the heart of the story.

Approach to history

Tacitus's historical style combines various approaches to history into a method of his own (owing some debt to Sallust): Seamlessly blending straightforward descriptions of events, pointed moral lessons and tightly-focused dramatic accounts, his historiography offers deep, and often pessimistic, insights into the workings of the human mind and the nature of power.Tacitus' own declaration regarding his approach to history is famous (''Ann.'' I,1): :{|- |inde consilium mihi ... tradere ... sine ira et studio, quorum causas procul habeo. | |Hence my purpose is to relate ... without either anger or zeal, from any motives to which I am far removed. |} There has been much scholarly discussion about Tacitus' "neutrality" (or "partiality" to others, which would make the quote above no more than a figure of speech).

Throughout his writing, Tacitus is concerned with the balance of power between the Senate and the Emperors, corruption and the growing tyranny among the governing classes of Rome as they adjust to the new imperial régime. In Tacitus' view, they squandered their cultural traditions of free speech and independence to placate the often bemused (and rarely benign) emperor.

Tacitus explored the emperors' increasing dependence on the goodwill of the armies to secure the ''principes''. The internecine murders of the Julio-Claudians eventually gave way to opportunist generals. These generals, backed by the legions they commanded, followed Julius Caesar's example (and that of Sulla and Pompey) in realising that military might could secure them the political power in Rome. Tacitus believed this realisation came with the death of Nero, (''Hist.1.4)

Welcome as the death of Nero had been in the first burst of joy, yet it had not only roused various emotions in Rome, among the Senators, the people, or the soldiery of the capital, it had also excited all the legions and their generals; for now had been divulged that secret of the empire, that emperors could be made elsewhere than at Rome.

Tacitus' political career was largely spent under the emperor Domitian; his experience of the tyranny, corruption, and decadence prevalent in the era (81–96) may explain his bitter and ironic political analysis. He warned against the dangers of unaccountable power, against the love of power untempered by principle, and against the popular apathy and corruption, engendered by the wealth of the empire, which allowed such evils to flourish. The experience of Domitian's tyrannical reign is generally also seen as the cause of the sometimes unfairly bitter and ironic cast to his portrayal of the Julio-Claudian emperors.

Nonetheless the image he builds of Tiberius throughout the first six books of the ''Annals'' is neither exclusively bleak nor approving: most scholars analyse the image of Tiberius as predominantly ''positive'' in the first books, becoming predominantly ''negative'' in the following books relating the intrigues of Sejanus. Even then, the entrance of Tiberius in the first chapters of the first book is a crimson tale dominated by hypocrisy by and around the new emperor coming to power; and in the later books some kind of respect for the wisdom and cleverness of the old emperor, keeping out of Rome to secure his position, is often transparent.

In general Tacitus does not fear to give words of praise and words of rejection to the same person, often explaining openly which he thinks the commendable and which the despicable properties. Not ''conclusively'' taking sides for or against the persons he describes is his hallmark, and led thinkers in later times to interpret his works to be, as well as a ''defense'' of an imperial system, also a ''rejection'' of the same (see Tacitean studies, ''Black'' vs. ''Red'' Tacitists). A better illustration of Tacitus' "sine ira et studio" is scarcely imaginable.

Prose style

Tacitus' skill with written Latin is unsurpassed; no other author is considered his equal, except perhaps for Cicero. His style differs both from the prevalent style of the Silver Age and from that of the Golden Age; though it has a calculated grandeur and eloquence (largely thanks to Tacitus' education in rhetoric), it is extremely concise, even epigrammatic—the sentences are rarely flowing or beautiful, but their point is always clear. The same style has been both derided as "harsh, unpleasant, and thorny" and praised as "grave, concise, and pithily eloquent".His historical works focus on the psyches and inner motivations of the characters, often with penetrating insight—though it is questionable how much of his insight is correct, and how much is convincing only because of his rhetorical skill. He is at his best when exposing hypocrisy and dissimulation; for example, he follows a narrative recounting Tiberius' refusal of the title ''pater patriae'' by recalling the institution of a law forbidding any "treasonous" speech or writings—and the frivolous prosecutions which resulted (''Annals'', 1.72). Elsewhere (''Annals'' 4.64–66) he compares Tiberius's public distribution of fire relief to his failure to stop the perversions and abuses of justice which he had begun. Although this kind of insight has earned him praise, he has also been criticised for ignoring the larger context of events. Of course, Tacitus wrote about comparatively recent events, whereas we have the benefit of twenty centuries' hindsight.

Tacitus owes most, both in language and in method, to Sallust, while Ammianus Marcellinus is the later historian whose work most closely approaches him in style.

Studies and reception history

From Pliny the Younger's 7th Letter (to Tacitus), §33: :{| |- | valign = "top" | Auguror nec me fallit augurium, historias tuas immortales futuras. | | | valign = "top" | I predict, and my predictions do not fail me, that your histories will be immortal. |}The historian was not much read in late antiquity, and even less in the Middle Ages. The very survival of any part of his major works into the post-Roman world was a tenuous affair. Only a third of his known work has survived and then through a very slim textual tradition; we depend on a single manuscript for books I-VI of the ''Annales'' and on another one for the other surviving half (books XI-XVI) and for the five books extant of the ''Historiae''. His handling of the language, as well as his antipathy towards the Jews and Christians of his time — he records with unemotional contempt the sufferings of the Christians at Rome during Nero's persecution — made him unpopular in the Middle Ages. He was rediscovered, however, by the Renaissance, whose writers were impressed with his dramatic presentation of the Imperial age.

Tacitus is remembered first and foremost as the greatest Roman historian. ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' opines that he "ranks beyond dispute in the highest place among men of letters of all ages." His work has been read for its moral instruction, for its dramatic narrative and for its prose style, but it is as a political theorist that he has been and remains most influential outside the field of history. The political lessons taken from his work fall roughly into two camps, as identified by Giuseppe Toffanin: the "red Tacitists," who used him to support republican ideals, and the "black Tacitists," who read him as a lesson in Machiavellian ''realpolitik''.

Although his work is the most reliable source for the history of his era, its factual accuracy is occasionally questioned. The ''Annals'' are based in part on secondary sources of unknown reliability, and there are some obvious mistakes, for instance the confusion of the two daughters of Mark Antony and Octavia Minor, both named Antonia. The ''Histories'', written from primary documents and intimate knowledge of the Flavian period, is thought to be more accurate, though Tacitus's hatred of Domitian seemingly colored its tone and interpretations.

See also

Notes

References

External links

Works by Tacitus

Category:50s births Category:2nd-century deaths Category:1st-century Romans Category:2nd-century Romans Category:1st-century writers Category:2nd-century writers Category:2nd-century historians Category:Ancient Roman rhetoricians Category:Latin historians Category:Roman era biographers Category:Ancient Roman jurists Category:Silver Age Latin writers

af:Tacitus als:Tacitus ar:تاسيتس bn:কর্নেলিয়ুস তাকিতুস br:Tacitus bg:Публий Корнелий Тацит ca:Tàcit cs:Tacitus cy:Tacitus da:Tacitus de:Tacitus et:Tacitus es:Tácito eo:Tacito (verkisto) ext:Tácitu eu:Kornelio Tazito fr:Tacite fy:Publius Kornelius Tasitus ga:Publius Cornelius Tacitus gl:Publio Cornelio Tácito ko:타키투스 hy:Կոռնելիոս Տակիտոս hr:Tacit ia:Tacito is:Tacítus it:Publio Cornelio Tacito he:טקיטוס ka:პუბლიუს კორნელიუს ტაციტუსი kk:Тацит Публий Корнелий la:Cornelius Tacitus lv:Gajs Kornēlijs Tacits lt:Publijus Kornelijus Tacitas hu:Publius Cornelius Tacitus nl:Publius Cornelius Tacitus nds-nl:Publius Cornelius Tacitus ja:タキトゥス no:Tacitus nn:Tacitus oc:Tacit pl:Publiusz Korneliusz Tacyt pt:Públio Cornélio Tácito ro:Tacit ru:Публий Корнелий Тацит sq:M. Kornel Taciti scn:Pubbliu Curneliu Tàcitu simple:Tacitus sk:Tacitus sl:Tacit Kornelij sr:Тацит sh:Tacit fi:Tacitus sv:Publius Cornelius Tacitus th:แทซิทัส tr:Tacitus uk:Публій Корнелій Тацит zh:塔西佗

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.