|

Interview by Anne Alexander, December 2011

The left and the Muslim Brotherhood in the Egyptian Doctors' Union A rank and file slate, including socialists, won major successes in recent elections to Egypt's Doctors' Union, long a bastion of the Muslim Brotherhood. Anne Alexander spoke to Mohammed Shafiq, an organiser of this electoral campaign and a doctor at Manshiyet al-Bakri hospital in Cairo

We took 25 percent of the seats on the general council of the Doctors' Union. We had no seats at all before. And we took at least 50 percent of the local union branches. The strongest branches of the union are the Cairo branch and the Alexandria branch, followed by Giza. In Cairo we took 14 out of 16 seats and in Alexandria ten out 12 seats, although we lost in Giza. Around 50 to 60 percent of Egypt's doctors are in those three governorates. The rest are not very significant.

Strikes in May

We organised two major strikes by doctors in May, and there were protest strikes in September, although these did not get massive support because they were calling for all-out rather than partial strikes. Most of the doctors who took strike action in May were employed in the public sector, although there were a few in private hospitals.

The rate of participation was very high. In Cairo it was around 60 to 65 percent. Overall 30,000 to 40,000 doctors took part in the strike, out of about 60,000 doctors in the public sector. And don't forget that not all of those were working; some are on study leave, taking examinations and so on. So in some governorates 100 percent of doctors were on strike. Suez, Isma'iliyya and Port Sa'id were among them.

These were the same governorates where the Muslim Brotherhood took no seats at all in the union elections. There is a direct relationship between participation in the strike and the disappearance of the Brotherhood. These are also the governorates where there are socialist activists present among the doctors. In Suez and Port Sa'id there is a marked presence of socialists among the doctors. They were the leadership of the movement there.

Hated union leader

The former president of the Doctors' Union was appointed by the old ruling party of the regime and "ruled" the union for more than 20 years. He was hated, really hated. After the revolution began on 25 January there were three emergency general assemblies. The first, on 25 March, discussed the doctors' demands. There was a physical fight between doctors mobilised by the old union leadership and Doctors Without Rights and the Doctors' Coalition, a network of young doctors.

We had a victory and won a statement of the doctors' basic demands. These were for a national wage structure - not just for the doctors - and that doctors should take their place in this national structure. This is a demand that most of the workers' movement has since taken up. The second demand was an increase in the health budget from 3 percent of the state budget to 10 to 15 percent. The third demand was the issue of security in the hospitals, and the fourth demand was for the resignation of the minister of health and the corrupt leadership with him.

President Gamal Abdel Nasser created the Egyptian Trade Union Federation and the legal framework for the professional unions in the 1950s. Just as he "nationalised" the political parties, he "nationalised" the unions. The Doctors' Union became part of the administrative structures of the state and the only organisation that could stand for election on a national scale was the ruling party.

Service union

The Brotherhood's idea was to turn the Doctors' Union into a service-oriented union. From the 1970s, under President Anwar Sadat, the state began withdrawing from public services with the beginning of the era of neoliberalism.

So the Brotherhood proposed to fill the gap. The union began to organise exhibitions and shows. It offered hire-purchase schemes to buy commodities, and provided treatment projects. It began to take on some of the state's duties in terms of social support which Nasser had initiated but the state had abandoned. The first union to fall to the Brotherhood was the Doctors' Union. They took control of the other professional unions during the 1980s and by the 1990s they controlled all of them.

The ruling party was not able to resist them. So the government issued Law 100 which froze the activities of the professional unions, stopping all their activities.

The professionals were the losers in all this. They had these "service unions" controlled by the Brotherhood, but no real union to defend them. Many people emigrated to the Gulf or Europe. During the 1990s the union was really dead. There was a deal between the Brotherhood and the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP). The president of the union and some members of the union branches were from the NDP, but the Brotherhood was able to use the union as a platform for its ideas.

After 11 September 2001 the possibilities of emigration to Europe or America for Egyptian doctors were reduced. There was also more competition with doctors from Pakistan and India in the labour market in the Gulf. At the same time the deterioration of the education system in Egypt hit them hard. An Egyptian MA used to be considered the equivalent of an MA in Britain in the 1950s and 60s. But as the quality of public education in Egypt declined, doctors found their qualifications were worth less and less. Even Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait started to prefer Pakistani and Indian doctors. So doctors and other professionals were in general oppressed during the 1990s and into the early 2000s. This pushed them in the direction of workers' struggles.

The rise of Doctors Without Rights

It was in this context that Doctors Without Rights was born. It is a group of trade unionists which offers a different conception of trade union activism: defending the interests of union members, including their material interests, and their social and economic rights. It began as a small group of a few dozen people, standing on the steps in front of the union headquarters, outside this huge organisation with money and a vast membership. It began to agitate and cause problems, and had some real successes, for example stopping one of the laws privatising part of the health service, and successfully fighting for an increase in the health budget.

It was central to the first attempt to organise a doctors' strike in 2008. The strike failed in 2008 because people thought the union would achieve what they wanted. There was a general assembly which took a decision to strike, and people got ready, but all the time the pressure from the state was increasing.

The strike was demanding the creation of a unified pay and grading structure for doctors. Teachers had achieved this already, and this encouraged the doctors. But there are 1 million teachers. And in any case, doctors are not like teachers: they have the means to escape some of the financial pressures. They can do an MA or PhD and travel abroad. They can cut their hours in the public hospitals and work in the private sector. So they have certain class privileges. But these are not available to all doctors, so resistance began to increase.

Failed attempts

In my view, there are no strikes which succeed straight away without failed attempts beforehand. In 2008 we faced pressure from the Central Security Forces (the riot police), threats of arrest and the treachery of the union's general council, which was being quoted every day in the press saying, "We're not going on strike." Then the government gave a small bonus to the junior doctors in their twenties who work in the hospitals, and they were the leadership of the movement. All of this combined to break the 2008 strike. The activists in 2008 were Doctors Without Rights, who were also the majority of the leadership in the 2011 strikes.

Doctors had begun to see that the union could have a different role. Instead of providing services, they realised it was supposed to defend them. There was a transformation in doctors' consciousness, and this caused a dilemma for the Brotherhood. Some of the Brotherhood's members were activists in Doctors Without Rights. And this contradiction continued until the revolution, and then the contradiction changed and it became a straightforward battle.

Failure of negotiations

After the general assembly of 25 March, and the failure of negotiations with the government to achieve the doctors' demands, another general assembly was held on 1 May. This time the Brotherhood mobilised all their supporters, and so did Doctors Without Rights and the Doctors' Coalition. And we won the decision to strike. It was a really intense battle.

Partial strikes took place on 10 and 17 May. The strikes were a great success in terms of organisation, but they didn't achieve their demands. In my view, they didn't succeed because the demands were beyond what the doctors alone could achieve. If you are asking the state to increase health spending to 10 percent of the state budget, you're talking about 60 billion Egyptian pounds. This is bigger than the budget for the police and the army. To win this you'd have to unite the nurses and the technicians and so on. You'd have to bring the whole of society behind you.

After the strike some of the younger doctors began to criticise Doctors Without Rights, and argue that there should be a call for an all-out strike without any cover: close down the whole hospital; shut down the intensive care unit; shut down A&E.; But this goes against uniting the whole of society behind you. There is a real problem as well with the morality of this kind of action, because we're talking about a service to people and not manufacturing.

The third general assembly was on 10 June. The Brotherhood had an all-out mobilisation for this assembly and they won a number of victories. The general assembly decided to renounce the demand calling for the resignation of the minister, and declared that there would be no more strikes and no more general assemblies. Everyone would be "one hand", and democracy would begin and end with the national anthem.

Tensions inside the Brotherhood

As a result the Brotherhood isolated themselves from the movement. You had people turning up to vote who hadn't been active, and had nothing to with building the union. It was ridiculous. The Brotherhood became hated for it. Of course they defended themselves strongly. But inside the Brotherhood there was a huge struggle going on with the younger members telling the leadership "Why did you do that?"

Some of the younger people who won the elections with the backing of the Brotherhood began to attack the ministry's decision to send newly-qualified doctors to governorates on the borders of Egypt.

They started saying "it is not on to send doctors out to these places without adequate training, where there are no facilities or public transport, without giving them any financial incentives for a posting of two years." They told the minister they wouldn't stand for it, and actually he rescinded the decision. We can win these people to a trade union perspective.

Independence list

The Independence list in the elections was broader than just Doctors Without Rights. It included the Tahrir Doctors and the Doctors for the Independence of the University. It was a coalition. The list put up six candidates for the young doctors' seats on the general council who are elected across the entire country. I was one of them. It is well known that I am a communist. The list got 10,000 votes. I got 12,000 votes in total. Those extra 2,000 votes came from the Brotherhood. I was putting forward the view that the union should be a fighting union, that the union is a shield and our sword is the strike.

We have long believed that the movement would change the Muslim Brotherhood, not necessarily that people would leave but that a small section of the membership, under pressure from the movement, would move to the left towards us. And it would create splits between the leadership and the membership.

In the union elections, the Brotherhood simply relied on mobilising their existing base to vote. Their electoral list was called "Doctors for Egypt", of which only 55 to 60 percent were from the Brotherhood. The rest were ordinary doctors, not involved in anything. Some of them were eminent people, some opportunists who just wanted to win a seat. And this is the danger for the Brotherhood.

Union elections

"For example, the general council has 24 seats, plus the president. We now have six elected from the Independence list. The other 18 include six who are not in the Brotherhood, who are eminent academics who went along with the Brotherhood because they wanted to win. This leaves them with 12 really.

It is the same in the branches. They don't have the cadres to cover the whole country. This was evident from the results of the six general council seats reserved for older doctors. The top three winning candidates in terms of numbers of votes were not from the Brotherhood. The fourth was from the Brotherhood, then Mona Mina from the Independence list, and the sixth was also from the Brotherhood.

The Brotherhood tried to attack us, especially Mona Mina and myself. I was attacked as an out and out communist - you know the traditional things about communists and atheists. Mona Mina was attacked because she is female and a Christian. They accused her of taking donations from the wealthy Christian businessman Naguib Sawiris and encouraging Christians to vote for Christians and Muslims for Muslims. They tried to make it like the Constitutional Referendum in March: Islam versus Christianity.

A history in the struggle

But this failed because Mona Mina is a figure in the union and has a history of struggle. I really thought they would succeed with me also, but they didn't, as I only just missed out on being elected, and beat around 40 other candidates for the general council seats. In the electoral statistics you see remarkable things.

Translated by Anne Alexander who spoke to Mohammed Shafiq in Cairo on 27 October |

By Corey Oakley for

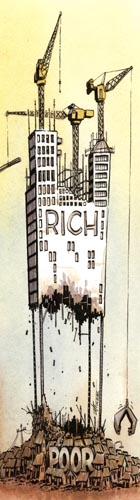

By Corey Oakley for  The dominant theme in world politics in 2011 is the generalised crisis of world capitalism. The economic crisis has contributed to two major developments: first, the deepening of the crises of US and EU imperialism, processes that were already under way even before the collapse of Lehman Brothers; and, second, the intensification of class struggle and popular resistance both in the imperialist core and the countries of the Middle East and North Africa.

The dominant theme in world politics in 2011 is the generalised crisis of world capitalism. The economic crisis has contributed to two major developments: first, the deepening of the crises of US and EU imperialism, processes that were already under way even before the collapse of Lehman Brothers; and, second, the intensification of class struggle and popular resistance both in the imperialist core and the countries of the Middle East and North Africa.