- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Ali Kushayb

Ali Muhammad Ali Abd-Al-Rahman, commonly known as Ali Kushayb, is a former senior Janjaweed commander supporting the Sudanese government against Darfur rebel groups, and currently is sought under an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes. He was known as aqid al oqada ("colonel of colonels") and was active in Wadi Salih, West Darfur. On February 27, 2007, Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo charged Kushayb with crimes against civilians in Darfur during 2003 and 2004, accusing him of ordering killings, rapes, and looting. An ICC arrest warrant was issued for him and Ahmed Haroun, his co-defendant, on April 27, 2007.

http://wn.com/Ali_Kushayb -

Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell (; born April 5, 1937) is an American statesman and a retired four-star general in the United States Army. He was the 65th United States Secretary of State (2001–2005), serving under President George W. Bush. He was the first African American appointed to that position. During his military career, Powell also served as National Security Advisor (1987–1989), as Commander of the U.S. Army Forces Command (1989) and as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1989–1993), holding the latter position during the Gulf War. He was the first, and so far the only, African American to serve on the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

http://wn.com/Colin_Powell -

Gregory Stanton

Gregory H. Stanton is the founder (1999) and president of Genocide Watch , the founder (1981) and director of the Cambodian Genocide Project, and the founder (1999) and Chair of the International Campaign to End Genocide. From 2007 to 2009 he was the President of the International Association of Genocide Scholars.

http://wn.com/Gregory_Stanton -

Helen Fein

Helen Fein (born 1934) is a historical sociologist, Professor, specialized on genocide, human rights, collective violence and other issues. She is an author and editor of 12 books and monographs, Associate of International Security Program (Harvard University), a founder and first President of the International Association of Genocide Scholars. She is the Executive Director of the Institute for the Study of Genocide (City University of New York).

http://wn.com/Helen_Fein -

Israel W. Charny

http://wn.com/Israel_W_Charny -

Jew

http://wn.com/Jew -

Leo Kuper

Leo Kuper (1908 - 1994) was a writer and philosopher. He was born to a Lithuanian Jewish family in South Africa. He trained as a lawyer before becoming a sociologist specialising in the study of genocide.

http://wn.com/Leo_Kuper -

nation

http://wn.com/nation -

nationality

http://wn.com/nationality -

Nikola Jorgic

Nikola Jorgic is a Bosnian Serb from the Doboj region who was the leader of a paramilitary group located in the Doboj region. In 1997, Nikola was convicted of genocide in Germany. This was the first conviction won against participants in the Bosnian Genocide. Nikola was sentenced to four terms of life imprisonment for his involvement in genocides in Bosnia.

http://wn.com/Nikola_Jorgic -

Omar al-Bashir

Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir (born 1944) is the current President of Sudan and the head of the National Congress Party. He came to power in 1989 when he, as a brigadier in the Sudanese army, led a group of officers in a bloodless military coup that ousted the government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi.

http://wn.com/Omar_al-Bashir -

Poles

The Polish people, or Poles ( , singular Polak) are the inhabitants of Poland and Polish emigrants irrespective of their ancestry. Their religion is predominantly Roman Catholic. As a nation, they are bounded by the Polish language, which belongs to the Lechitic subgroup of west slavic languages of Central Europe. A wide-ranging Polish diaspora exists throughout Western and Eastern Europe, the Americas and Australia. Polish citizens live predominantly in Poland.

http://wn.com/Poles -

R. J. Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (born October 21, 1932) is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Hawaii. He has spent his career assembling data on collective violence and war with a view toward helping their resolution or elimination. Rummel coined the term democide for murder by government, his research claiming that six times as many people died of democide during the 20th century than in all that century's wars combined. He concludes that democracy is the form of government least likely to kill its citizens and that democracies do not wage war against each other (see Democratic peace theory).

http://wn.com/R_J_Rummel -

Radislav Krstic

http://wn.com/Radislav_Krstic -

Radovan Karadzic

http://wn.com/Radovan_Karadzic -

Ratko Mladic

http://wn.com/Ratko_Mladic -

Simele Massacre

http://wn.com/Simele_Massacre -

Slobodan Milosevic

http://wn.com/Slobodan_Milosevic -

Srebrenica Genocide

http://wn.com/Srebrenica_Genocide -

Srebrenica massacre

The Srebrenica massacre, also known as the Srebrenica genocide, refers to the July 1995 killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys, as well as the ethnic cleansing of another 25,000–30,000 refugees, in and around the town of Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina, by units of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of General Ratko Mladić during the Bosnian War. A paramilitary unit from Serbia known as the Scorpions, officially part of the Serbian Interior Ministry until 1991, participated in the massacre. It is alleged that foreign volunteers including the Greek Volunteer Guard also participated.

http://wn.com/Srebrenica_massacre

-

Bahrain

Bahrain, officially Kingdom of Bahrain (, , literally: "Kingdom of the Two Seas"), is a small island country in the Persian Gulf ruled by the Al Khalifa royal family. While Bahrain is an archipelago of thirty-three islands, the largest (Bahrain Island) is long by wide. Saudi Arabia lies to the west and is connected to Bahrain via the King Fahd Causeway, which was officially opened on 25 November 1986. Qatar is to the southeast across the Gulf of Bahrain.

http://wn.com/Bahrain -

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (; , '), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh (Bengali: গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ ') is a country in South Asia. It is bordered by India on all sides except for a small border with Burma (Myanmar) to the far southeast and by the Bay of Bengal to the south. Together with the Indian state of West Bengal, it makes up the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal. The name Bangladesh means "Country of Bengal" in the official Bengali language.

http://wn.com/Bangladesh -

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. By 1922 the British Empire held sway over about 458 million people, one-quarter of the world's population at the time, and covered more than 13 million square miles (34 million km2), almost a quarter of the Earth's total land area. As a result, its political, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, it was often said that "the sun never sets on the British Empire" because its span across the globe ensured that the sun was always shining on at least one of its numerous territories.

http://wn.com/British_Empire -

Cambodia

The "Kingdom of Cambodia" "Royaume du Cambodge" (official name), also known as Cambodia, derived from Sanskrit Kambujadesa ()), is a country in Southeast Asia that borders Thailand to the west and northwest, Laos to the northeast, Vietnam to the east, and the Gulf of Thailand to the southwest. The geography of Cambodia is dominated by rivers and a lake namely: The Mekong River (Upper and Lower) (Khmer: ទន្លេមេគង្គ Tonlé Mékong Pronounced: Tonlé Mékung = Mother Water River), Sab River Tonlé Sap (Khmer: ទន្លេសាប Pronounced: Tonlé Sab = Fresh Water River), Bassac River Tonlé Bassac (Khmer: ទន្លេបាសាក់ Pronounced: Tonlé Bassuck = ?)

http://wn.com/Cambodia -

Cyprus

Cyprus (; , Kýpros, ; ), – officially the Republic of Cyprus (, Kypriakī́ Dīmokratía, ; ) – is a Eurasian island country in the Eastern Mediterranean, south of Turkey and west of Syria and Lebanon. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of its most popular tourist destinations. An advanced, high-income economy with a very high Human Development Index, the Republic of Cyprus was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement until it joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.

http://wn.com/Cyprus -

FBI

http://wn.com/FBI -

France

{{Infobox Country

http://wn.com/France -

Germany

Germany (), officially the Federal Republic of Germany (, ), is a country in Western Europe. It is bordered to the north by the North Sea, Denmark, and the Baltic Sea; to the east by Poland and the Czech Republic; to the south by Austria and Switzerland; and to the west by France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The territory of Germany covers 357.021 km2 and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With 81.8 million inhabitants, it is the most populous member state of the European Union, and home to the third-largest number of international migrants worldwide.

http://wn.com/Germany -

India

India (), officially the Republic of India ( ; see also official names of India), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.18 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world. Mainland India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the west, and the Bay of Bengal on the east; and it is bordered by Pakistan to the west; Bhutan, the People's Republic of China and Nepal to the north; and Bangladesh and Burma to the east. In the Indian Ocean, mainland India and the Lakshadweep Islands are in the vicinity of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, while India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands share maritime border with Thailand and the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the Andaman Sea. India has a coastline of .

http://wn.com/India -

Malaysia

Malaysia (pronounced or ) is a federal constitutional monarchy in Southeast Asia. It consists of thirteen states and three federal territories and has a total landmass of . The country is separated by the South China Sea into two regions, Peninsular Malaysia and Malaysian Borneo (also known as West and East Malaysia respectively). Malaysia shares land borders with Thailand, Indonesia, and Brunei and has maritime boundaries with Singapore, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The capital city is Kuala Lumpur, while Putrajaya is the seat of the federal government. The population as of 2009 stood at over 28 million.

http://wn.com/Malaysia -

McGill University

McGill University is a research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Its undergraduate, graduate, and professional schools consistently top national and international rankings, such as those published by ''Maclean's'' and the Financial Times, and among the top 20 universities in worldwide rankings such as the Times Higher Education (THE) – QS World University Rankings and US News & World Report's World's Best Universities.

http://wn.com/McGill_University -

Norway

Norway (; Norwegian: (Bokmål) or (Nynorsk)), officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe occupying the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, as well as Jan Mayen and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.8 million. It is one of the most sparsely populated countries in Europe. The majority of the country shares a border to the east with Sweden; its northernmost region is bordered by Finland to the south and Russia to the east; and Denmark lies south of its southern tip across the Skagerrak Strait. The capital city of Norway is Oslo. Norway's extensive coastline, facing the North Atlantic Ocean and the Barents Sea, is home to its famous fjords.

http://wn.com/Norway -

Nuremberg trials

http://wn.com/Nuremberg_trials -

Philippines

The Philippines ( ), officially known as the Republic of the Philippines (), is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam. The Sulu Sea to the southwest lies between the country and the island of Borneo, and to the south the Celebes Sea separates it from other islands of Indonesia. It is bounded on the east by the Philippine Sea. Its location on the Pacific Ring of Fire and its tropical climate make the Philippines prone to earthquakes and typhoons but have also endowed the country with natural resources and made it one of the richest areas of biodiversity in the world. An archipelago comprising 7,107 islands, the Philippines is categorized broadly into three main geographical divisions: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Its capital city is Manila.

http://wn.com/Philippines -

Republic of China

The Republic of China (ROC), commonly known as Taiwan, is a state in East Asia located off the east coast of mainland China. Subject to an ongoing dispute with the People's Republic of China (PRC) that has left it with limited formal diplomatic relations, the government of the Republic of China currently governs the islands of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor islands. Neighbouring states include the People's Republic of China to the west, Japan to the northeast, and the Philippines to the south.

http://wn.com/Republic_of_China -

Rwanda

The Republic of Rwanda (, , or in English, or in Kinyarwanda) is a unitary republic of central and eastern Africa. It borders Uganda to the north; Tanzania to the east; Burundi to the south; and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west. Rwanda is landlocked but is noted for its lakes, particularly Lake Kivu, which occupies the floor of the Rift Valley along most of the country's western border. Although close to the equator, the country has a temperate climate due to its high elevation, with the highest point being Mount Karisimbi. The terrain consists of mountains and gently rolling hills, with plains and swamps in the east. Abundant wildlife, including rare mountain gorillas, have led to a fast-growing tourism sector. The largest cities in Rwanda are Kigali, Gitarama, and Butare. Unlike many African countries, Rwanda is home to only one significant ethnic and linguistic group, the Banyarwanda. The country is well known for its native styles of dance, particularly the Intore dance, and for its drummers. Kinyarwanda, English and French are the official languages.

http://wn.com/Rwanda -

Singapore

{{Infobox Country

http://wn.com/Singapore -

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, , abbreviated СССР, SSSR), informally known as the Soviet Union () or Soviet Russia, was a constitutionally socialist state that existed on the territory of most of the former Russian Empire in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991.

http://wn.com/Soviet_Union -

Srebrenica

Srebrenica (Cyrillic: Сребреница, ) is a town and municipality in the east of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Srebrenica is a small mountain town, its main industry being salt mining and a nearby spa. During the Bosnian War, it was the site of the Srebrenica massacre, determined to have been a crime of genocide. On March 24, 2007, Srebrenica's municipal assembly adopted a resolution demanding independence from the Republika Srpska; the Serb members of the assembly did not vote on the resolution.

http://wn.com/Srebrenica -

Sudan

Sudan (), officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in northeastern Africa. It is the largest country in Africa and the Arab world, and tenth largest in the world by area. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east,Kenya and Uganda to the southeast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya to the northwest. The world's longest river, the Nile, divides the country between east and west sides.

http://wn.com/Sudan -

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (commonly known as the United Kingdom, the UK, or Britain) is a country and sovereign state located off the northwestern coast of continental Europe. It is an island nation, spanning an archipelago including Great Britain, the northeastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller islands. Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK with a land border with another sovereign state, sharing it with the Republic of Ireland. Apart from this land border, the UK is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea, the English Channel and the Irish Sea. Great Britain is linked to continental Europe by the Channel Tunnel.

http://wn.com/United_Kingdom -

United States

The United States of America (also referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district. The country is situated mostly in central North America, where its forty-eight contiguous states and Washington, D.C., the capital district, lie between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The state of Alaska is in the northwest of the continent, with Canada to the east and Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. The state of Hawaii is an archipelago in the mid-Pacific. The country also possesses several territories in the Caribbean and Pacific.

http://wn.com/United_States -

Vietnam

Vietnam ( ; , ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (, ), is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by People's Republic of China (PRC) to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea, referred to as East Sea (), to the east. With a population of over 86 million, Vietnam is the 13th most populous country in the world.

http://wn.com/Vietnam -

Yemen

Yemen (Arabic: اليَمَن al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen (Arabic: الجمهورية اليمنية al-Jumhuuriyya al-Yamaniyya) is a country located on the Arabian Peninsula in Southwest Asia. It has an estimated population of more than 23 million people and is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Aden to the south, and Oman to the east.

http://wn.com/Yemen -

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (Croatian, Serbian, Slovene: Jugoslavija; Macedonian, Serbian Cyrillic: Југославија) is a term that describes three political entities that existed successively on the western part of Balkan Peninsula in Europe, during most of the 20th century.

http://wn.com/Yugoslavia

- A Problem from Hell

- ad hoc

- Ahmad Harun

- Ali Kushayb

- Armenian Genocide

- Associated Press

- Assyrian Genocide

- Autogenocide

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- BBC

- British Empire

- Cambodia

- Colin Powell

- CPPCG

- custom (law)

- Cyprus

- Darfur

- Darfur conflict

- dehumanization

- democide

- denial

- Dirk Moses

- erga omnes

- ethnic cleansing

- ethnic group

- ethnicity

- FBI

- France

- Gendercide

- Genocide

- Genocide Convention

- genocide definitions

- Genocide denial

- Genocide Watch

- Germany

- great powers

- Greek genocide

- Greek language

- Gregory Stanton

- Hate groups

- hate speech

- Helen Fein

- Holocaust

- human rights

- ICTR

- India

- international law

- Israel W. Charny

- Janjaweed

- Jean Akayesu

- Jean Kambanda

- Jew

- Jorgic v. Germany

- Khmer Rouge

- Kosovo War

- Latin

- legal

- Leo Kuper

- Ljubiša Beara

- Malaysia

- McGill University

- militia

- municipal law

- nation

- nationality

- Nazi eugenics

- Nikola Jorgic

- Norway

- Nuremberg trials

- Omar al-Bashir

- Oxfam

- paradigm

- peremptory norm

- Philippines

- plea bargain

- pogrom

- Poles

- Policide

- politicide

- propaganda

- PublicAffairs

- R. J. Rummel

- Racial integration

- Radislav Krstic

- Radovan Karadzic

- Raphael Lemkin

- Ratko Mladic

- religion

- Republic of China

- Routledge

- Rwanda

- Rwandan Genocide

- Simele Massacre

- Singapore

- Slobodan Milosevic

- Soviet Union

- Srebrenica

- Srebrenica Genocide

- Srebrenica massacre

- Sudan

- treaty

- tribunals

- UN Security Council

- United Kingdom

- United Nations

- United States

- vandalism

- Vietnam

- Vujadin Popović

- war crimes

- War in Darfur

- Western world

- World War II

- Yemen

- Yugoslavia

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:01

- Published: 12 Nov 2009

- Uploaded: 01 Jan 2012

- Author: CenturyMedia

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:57

- Published: 06 Aug 2007

- Uploaded: 27 Dec 2011

- Author: Vagabonding

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:41

- Published: 26 Nov 2009

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: InsaneVortex

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:05

- Published: 28 Jul 2008

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: africaproject

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:44

- Published: 07 Dec 2008

- Uploaded: 30 Dec 2011

- Author: Nortikka666

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:33

- Published: 07 Feb 2010

- Uploaded: 01 Jan 2012

- Author: TheThinkingAtheist

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:39

- Published: 23 May 2008

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: journeymanpictures

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:17

- Published: 01 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 28 Dec 2011

- Author: hokulani78

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:45

- Published: 21 Sep 2008

- Uploaded: 30 Dec 2011

- Author: TheFellow75

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:49

- Published: 18 Oct 2009

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: metalmeltdown12

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:20

- Published: 16 Nov 2006

- Uploaded: 27 Dec 2011

- Author: capenobvious

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:20

- Published: 17 Sep 2009

- Uploaded: 23 Dec 2011

- Author: wesseboyman

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:01

- Published: 07 Nov 2009

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: pacoelasesino

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:39

- Published: 15 May 2010

- Uploaded: 30 Dec 2011

- Author: landofthefreeuk

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:59

- Published: 13 Feb 2009

- Uploaded: 30 Dec 2011

- Author: qrUngestyLe

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:51

- Published: 14 Aug 2009

- Uploaded: 28 Dec 2011

- Author: mylittleponies322

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:52

- Published: 05 May 2010

- Uploaded: 31 Dec 2011

- Author: Armenoid65

size: 8.5Kb

size: 2.1Kb

-

The Threat of War Against Iran and Syria is Real

GlobalResearch

The Threat of War Against Iran and Syria is Real

GlobalResearch

-

China prepares for lift-off with mission to land on the Moon

The Independent

China prepares for lift-off with mission to land on the Moon

The Independent

-

Iran test fires long range missiles, amid nuclear tensions

Ha'aretz

Iran test fires long range missiles, amid nuclear tensions

Ha'aretz

-

North Korea's new leadership lashes out at South Korea

The Star

North Korea's new leadership lashes out at South Korea

The Star

-

US steps up sanctions as Iran floats nuclear talks

Zeenews

US steps up sanctions as Iran floats nuclear talks

Zeenews

- A Problem from Hell

- ad hoc

- Ahmad Harun

- Ali Kushayb

- Armenian Genocide

- Associated Press

- Assyrian Genocide

- Autogenocide

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- BBC

- British Empire

- Cambodia

- Colin Powell

- CPPCG

- custom (law)

- Cyprus

- Darfur

- Darfur conflict

- dehumanization

- democide

- denial

- Dirk Moses

- erga omnes

- ethnic cleansing

- ethnic group

- ethnicity

- FBI

- France

- Gendercide

- Genocide

- Genocide Convention

- genocide definitions

- Genocide denial

- Genocide Watch

- Germany

- great powers

- Greek genocide

- Greek language

- Gregory Stanton

- Hate groups

- hate speech

- Helen Fein

- Holocaust

- human rights

- ICTR

- India

- international law

- Israel W. Charny

- Janjaweed

- Jean Akayesu

- Jean Kambanda

- Jew

- Jorgic v. Germany

- Khmer Rouge

- Kosovo War

- Latin

- legal

- Leo Kuper

size: 13.7Kb

size: 5.0Kb

size: 10.3Kb

size: 3.3Kb

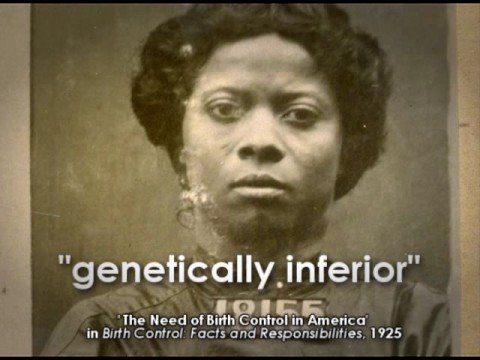

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, Race (classification of humans) , religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars. While a precise definition varies among genocide scholars, a legal definition is found in the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). Article 2 of this convention defines genocide as "any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life, calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."

The preamble to the CPPCG states that instances of genocide have taken place throughout history, but it was not until Raphael Lemkin coined the term and the prosecution of perpetrators of the Holocaust at the Nuremberg trials that the United Nations agreed to the CPPCG which defined the crime of genocide under international law.

During a video interview with Raphael Lemkin, the interviewer asked him about how he came to be interested in this genocide. He replied; "I became interested in genocide because it happened so many times. First to the Armenians, then after the Armenians, Hitler took action.".

There was a gap of more than forty years between the CPPCG coming into force and the first prosecution under the provisions of the treaty. To date all international prosecutions of genocide, the Rwandan Genocide and the Srebrenica Genocide, have been by ad hoc international tribunals. The International Criminal Court came into existence in 2002 and it has the authority to try people from the states that have signed the treaty, but to date it has not tried anyone.

Since the CPPCG came into effect in January 1951 about 80 member states of the United Nations have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of the CPPCG into their domestic law, and some perpetrators of genocide have been found guilty under such municipal laws, such as Nikola Jorgic, who was found guilty of genocide in Bosnia by a German court (Jorgic v. Germany).

Critics of the CPPCG point to the narrow definition of the groups that are protected under the treaty, particularly the lack of protection for political groups for what has been termed politicide (politicide is included as genocide under some municipal jurisdictions). One of the problems was that until there was a body of case law from prosecutions, the precise definition of what the treaty meant had not been tested in court, for example, what precisely does the term "in part" mean? As more perpetrators are tried under international tribunals and municipal court cases, a body of legal arguments and legal interpretations are helping to address these issues.

The exclusion of political groups and politically motivated violence from the international definition of genocide is particularly controversial. The reason for this exclusion is because a number of UN member nations insisted on it when the Genocide Convention was being drafted in 1948. They argued that political groups are too vaguely defined, as well as temporary and unstable. They further held that international law should not seek to regulate or limit political conflicts, since that would give the UN too much power to interfere in the internal affairs of sovereign nations. In the years since then, critics have argued that the exclusion of political groups from the definition, as well as the lack of a specific reference to the destruction of a social group through the forcible removal of a population, was designed to protect the Soviet Union and the Western Allies from possible accusations of genocide in the wake of World War II.

Another criticism of the CPPCG is that when its provisions have been invoked by the United Nations Security Council, they have only been invoked to punish those who have already committed genocide and been foolish enough to leave a paper trail. It was this criticism that led to the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1674 by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006 commits the Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict and to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity.

Genocide scholars such as Gregory Stanton have postulated that conditions and acts that often occur before, during, and after genocide—such as dehumanization of victim groups, strong organization of genocidal groups, and denial of genocide by its perpetrators—can be identified and actions taken to stop genocides before they happen. Critics of this approach such as Dirk Moses assert that this is unrealistic and that, for example, "Darfur will end when it suits the great powers that have a stake in the region".

Etymology

The term "genocide" was coined by Raphael Lemkin (1900–1959), a Polish-Jewish legal scholar, in 1944, firstly from the Greek root génos (γένος) (birth, race, stock, kind); secondly from Latin -cidium (cutting, killing) via French -cide.In 1933 Lemkin wrote a proposal on the "crime of barbarity" to be presented to the Legal Council of the League of Nations in Madrid. This was his first formal attempt at creating a law against what he would later call genocide. The concept originated in his youth when he first heard of the Ottoman government's mass killings (Armenian Genocide) of its Christian population during the First World War and the renewed round of anti-Assyrian persecution in Iraq. His proposal failed, and his work incurred the disapproval of the Polish government, which was at the time pursuing a policy of conciliation with Nazi Germany.

In 1944, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published Lemkin's most important work, entitled Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, in the United States. This book included an extensive legal analysis of German rule in countries occupied by Nazi Germany during the course of World War II, along with the definition of the term genocide ("the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group").

Lemkin's idea of genocide as an offense against international law was widely accepted by the international community and was one of the legal bases of the Nuremberg Trials (the indictment of the 24 Nazi leaders specifies in Count 3 that the defendants "conducted deliberate and systematic genocide—namely, the extermination of racial and national groups...") Lemkin presented a draft resolution for a Genocide Convention treaty to a number of countries in an effort to persuade them to sponsor the resolution. With the support of the United States, the resolution was placed before the General Assembly for consideration. In 1943, Lemkin wrote:

Genocide as a crime

International law

In the wake of the Holocaust, Lemkin successfully campaigned for the universal acceptance of international laws defining and forbidding genocide. In 1946, the first session of the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that "affirmed" that genocide was a crime under international law, but did not provide a legal definition of the crime. In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide which legally defined the crime of genocide for the first time.The CPPCG was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and came into effect on 12 January 1951 (Resolution 260 (III)). It contains an internationally-recognized definition of genocide which was incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many countries, and was also adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the treaty that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Convention (in article 2) defines genocide:

The first draft of the Convention included political killings, but the USSR along with some other nations would not accept that actions against groups identified as holding similar political opinions or social status would constitute genocide, so these stipulations were subsequently removed in a political and diplomatic compromise.

Intent to destroy

In 2007 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), noted in its judgement on Jorgic v. Germany case that in 1992 the majority of legal scholars took the narrow view that "intent to destroy" in the CPPCG meant the intended physical-biological destruction of the protected group and that this was still the majority opinion. But the ECHR also noted that a minority took a broader view and did not consider biological-physical destruction was necessary as the intent to destroy a national, racial, religious or ethnical group was enough to qualify as genocide.In the same judgement the ECHR reviewed the judgements of several international and municipal courts judgements. It noted that International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the International Court of Justice had agreed with the narrow interpretation, that biological-physical destruction was necessary for an act to qualify as genocide. The ECHR also noted that at the time of its the judgement, apart from courts in Germany which had taken a broad view, that there had been few cases of genocide under other Convention States municipal laws and that "There are no reported cases in which the courts of these States have defined the type of group destruction the perpetrator must have intended in order to be found guilty of genocide".

In part

The phrase "in whole or in part" has been subject to much discussion by scholars of international humanitarian law. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001) that Genocide had been committed. In Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004) paragraphs 8, 9, 10, and 11 addressed the issue of in part and found that "the part must be a substantial part of that group. The aim of the Genocide Convention is to prevent the intentional destruction of entire human groups, and the part targeted must be significant enough to have an impact on the group as a whole." The Appeals Chamber goes into details of other cases and the opinions of respected commentators on the Genocide Convention to explain how they came to this conclusion.The judges continue in paragraph 12, "The determination of when the targeted part is substantial enough to meet this requirement may involve a number of considerations. The numeric size of the targeted part of the group is the necessary and important starting point, though not in all cases the ending point of the inquiry. The number of individuals targeted should be evaluated not only in absolute terms, but also in relation to the overall size of the entire group. In addition to the numeric size of the targeted portion, its prominence within the group can be a useful consideration. If a specific part of the group is emblematic of the overall group, or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of Article 4 [of the Tribunal's Statute]."

In paragraph 13 the judges raise the issue of the perpetrators' access to the victims: "The historical examples of genocide also suggest that the area of the perpetrators’ activity and control, as well as the possible extent of their reach, should be considered. ... The intent to destroy formed by a perpetrator of genocide will always be limited by the opportunity presented to him. While this factor alone will not indicate whether the targeted group is substantial, it can—in combination with other factors—inform the analysis."

CPPCG coming into force

After the minimum 20 countries became parties to the Convention, it came into force as international law on 12 January 1951. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC) were parties to the treaty: France and the Republic of China. Eventually the Soviet Union ratified in 1954, the United Kingdom in 1970, the People's Republic of China in 1983 (having replaced the Taiwan-based Republic of China on the UNSC in 1971), and the United States in 1988. This long delay in support for the Genocide Convention by the world's most powerful nations caused the Convention to languish for over four decades. Only in the 1990s did the international law on the crime of genocide begin to be enforced.

Security Council responsibility to protect

UN Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity". The resolution committed the Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

Municipal law

Since the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) came into effect in January 1951 about 80 member states of the United Nations have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of the CPPCG into their municipal law.

Criticisms of the CPPCG and other definitions of genocide

William Schabas has suggested that a permanent body as recommended by the Whitaker Report to monitor the implementation of the Genocide Convention, and require States to issue reports on their compliance with the convention (such as were incorporated into the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture), would make the convention more effective.

Writing in 1998 Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Björnson stated that the CPPCG was a legal instrument resulting from a diplomatic compromise. As such the wording of the treaty is not intended to be a definition suitable as a research tool, and although it is used for this purpose, as it has an international legal credibility that others lack, other definitions have also been postulated. Jonassohn and Björnson go on to say that none of these alternative definitions have gained widespread support for various reasons.

Jonassohn and Björnson postulate that the major reason why no single generally accepted genocide definition has emerged is because academics have adjusted their focus to emphasise different periods and have found it expedient to use slightly different definitions to help them interpret events. For example Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn studied the whole of human history, while Leo Kuper and R. J. Rummel in their more recent works concentrated on the 20th century, and Helen Fein, Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr have looked at post World War II events. Jonassohn and Björnson are critical of some of these studies arguing that they are too expansive and concludes that the academic discipline of genocide studies is too young to have a canon of work on which to build an academic paradigm.

The exclusion of social and political groups as targets of genocide in the CPPCG legal definition has been criticized by some historians and sociologists, for example M. Hassan Kakar in his book The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982 argues that the international definition of genocide is too restricted, and that it should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator and quotes Chalk and Jonassohn: "Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpetrator." While there are various definitions of the term, Adam Jones states that the majority of genocide scholars consider that "intent to destroy" is a requirement for any act to be labelled genocide, and that there is growing agreement on the inclusion of the physical destruction criterion.

Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr defined genocide as "the promotion and execution of policies by a state or its agents which result in the deaths of a substantial portion of a group ...[when] the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality." Harff and Gurr also differentiate between genocides and politicides by the characteristics by which members of a group are identified by the state. In genocides, the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality. In politicides the victim groups are defined primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups. Daniel D. Polsby and Don B. Kates, Jr. state that "... we follow Harff's distinction between genocides and 'pogroms,' which she describes as 'short-lived outbursts by mobs, which, although often condoned by authorities, rarely persist.' If the violence persists for long enough, however, Harff argues, the distinction between condonation and complicity collapses."

According to R. J. Rummel, genocide has 3 different meanings. The ordinary meaning is murder by government of people due to their national, ethnic, racial, or religious group membership. The legal meaning of genocide refers to the international treaty, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This also includes non-killings that in the end eliminate the group, such as preventing births or forcibly transferring children out of the group to another group. A generalized meaning of genocide is similar to the ordinary meaning but also includes government killings of political opponents or otherwise intentional murder. It is to avoid confusion regarding what meaning is intended that Rummel created the term democide for the third meaning.

A major criticism of the international community's response to the Rwandan Genocide was that it was reactive, not proactive. The international community has developed a mechanism for prosecuting the perpetrators of genocide but has not developed the will or the mechanisms for intervening in a genocide as it happens. Critics point to the Darfur conflict and suggest that if anyone is found guilty of genocide after the conflict either by prosecutions brought in the International Criminal Court or in an ad hoc International Criminal Tribunal, this will confirm this perception.

International prosecution of genocide

By ad hoc tribunals

All signatories to the CPPCG are required to prevent and punish acts of genocide, both in peace and wartime, though some barriers make this enforcement difficult. In particular, some of the signatories—namely, Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam, Yemen, and Yugoslavia—signed with the proviso that no claim of genocide could be brought against them at the International Court of Justice without their consent. Despite official protests from other signatories (notably Cyprus and Norway) on the ethics and legal standing of these reservations, the immunity from prosecution they grant has been invoked from time to time, as when the United States refused to allow a charge of genocide brought against it by Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War.It is commonly accepted that, at least since World War II, genocide has been illegal under customary international law as a peremptory norm, as well as under conventional international law. Acts of genocide are generally difficult to establish for prosecution, because a chain of accountability must be established. International criminal courts and tribunals function primarily because the states involved are incapable or unwilling to prosecute crimes of this magnitude themselves.

Nuremberg Trials

Because the universal acceptance of international laws, defining and forbidding genocide was achieved in 1948, with the promulgation of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), those criminals who were prosecuted after the war in international courts, for taking part in the Holocaust were found guilty of crimes against humanity and other more specific crimes like murder. Nevertheless the Holocaust is universally recognized to have been a genocide and the term, that had been coined the year before by Raphael Lemkin, appeared in the indictment of the 24 Nazi leaders, Count 3, stated that all the defendants had "conducted deliberate and systematic genocide—namely, the extermination of racial and national groups..."

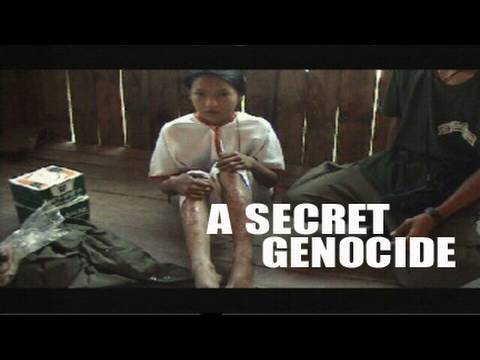

Cambodia

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, commonly known as the "Khmer Rouge Tribunal", is a national court established pursuant to an agreement between the Royal Government of Cambodia and the United Nations to try senior members of the Khmer Rouge for serious violations of Cambodian penal law, international humanitarian law and custom, and violation of international conventions recognized by Cambodia, committed during the period between 17 April 1975 and 6 January 1979. This includes crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide.

Rwanda

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offenses committed in Rwanda during the genocide which occurred there during April, 1994, commencing on 6 April. The ICTR was created on 8 November 1994 by the Security Council of the United Nations in order to judge those people responsible for the acts of genocide and other serious violations of the international law performed in the territory of Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994.So far, the ICTR has finished nineteen trials and convicted twenty seven accused persons. On December 14, 2009 two more men were accused and convicted for their crimes. Another twenty five persons are still on trial. Twenty-one are awaiting trial in detention, two more added on December 14, 2009. Ten are still at large. The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu, began in 1997. In October, 1998, Akayesu was sentenced to life imprisonment. Jean Kambanda, interim Prime Minister, pled guilty.

Former Yugoslavia

The term Bosnian Genocide is used to refer either to the genocide committed by Serb forces in Srebrenica in 1995, or to ethnic cleansing that took place during the 1992–1995 Bosnian War (an interpretation rejected by a majority of scholars).In 2001 the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) judged that the 1995 Srebrenica massacre was an act of genocide.

On 26 February 2007 the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in the Bosnian Genocide Case upheld the ICTY's earlier finding that the Srebrenica massacre constituted genocide, but found that the Serbian government had not participated in a wider genocide on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, as the Bosnian government had claimed.

On 12 July 2007, European Court of Human Rights when dismissing the appeal by Nikola Jorgic against his conviction for genocide by a German court (Jorgic v. Germany) noted that the German courts wider interpretation of genocide has since been rejected by international courts considering similar cases. The ECHR also noted that in the 21st century "Amongst scholars, the majority have taken the view that ethnic cleansing, in the way in which it was carried out by the Serb forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina in order to expel Muslims and Croats from their homes, did not constitute genocide. However, there are also a considerable number of scholars who have suggested that these acts did amount to genocide"

About 30 people have been indicted for participating in genocide or complicity in genocide during the early 1990s in Bosnia. To date after several plea bargains and some convictions that were successfully challenged on appeal two men, Vujadin Popović and Ljubiša Beara, have been found guilty of genocide, and two others, Radislav Krstic and Drago Nikolic, have been found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide. Three others have been found guilty of participating in genocides in Bosnia by German courts, one of whom Nikola Jorgic lost an appeal against his conviction in the European Court of Human Rights. A further eight men, former members of the Bosnian Serb security forces were found guilty of genocide by the State Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (See List of Bosnian genocide prosecutions).

Slobodan Milosevic, as the former President of Serbia and of Yugoslavia was the most senior political figure to stand trial at the ICTY. He died on 11 March 2006 during his trial where he was accused of genocide or complicity in genocide in territories within Bosnia and Herzegovina, so no verdict was returned. In 1995 the ICTY issued a warrant for the arrest of Bosnian Serbs Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic on several charges including genocide. On 21 July 2008, Karadzic was arrested in Belgrade, and he is currently in The Hague on trial accused of genocide among other crimes. Ratko Mladic was arrested on May 26, 2011 by Serbian special police in Lazarevo, Serbia.

By the International Criminal Court

To date all international prosecutions for genocide have been brought in specially convened international tribunals. Since 2002, the International Criminal Court can exercise its jurisdiction if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute genocide, thus being a "court of last resort," leaving the primary responsibility to exercise jurisdiction over alleged criminals to individual states. Due to the United States concerns over the ICC, the United States prefers to continue to use specially convened international tribunals for such investigations and potential prosecutions.

Darfur, Sudan

The on-going conflict in Darfur, Sudan, which started in 2003, was declared a "genocide" by United States Secretary of State Colin Powell on 9 September 2004 in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Since that time however, no other permanent member of the UN Security Council followed suit. In fact, in January 2005, an International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur, authorized by UN Security Council Resolution 1564 of 2004, issued a report to the Secretary-General stating that "the Government of the Sudan has not pursued a policy of genocide." Nevertheless, the Commission cautioned that "The conclusion that no genocidal policy has been pursued and implemented in Darfur by the Government authorities, directly or through the militias under their control, should not be taken in any way as detracting from the gravity of the crimes perpetrated in that region. International offences such as the crimes against humanity and war crimes that have been committed in Darfur may be no less serious and heinous than genocide."

In March 2005, the Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, taking into account the Commission report but without mentioning any specific crimes. Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution. As of his fourth report to the Security Council, the Prosecutor has found "reasonable grounds to believe that the individuals identified [in the UN Security Council Resolution 1593] have committed crimes against humanity and war crimes," but did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute for genocide.

In April 2007, the Judges of the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Harun, and a Militia Janjaweed leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.

On 14 July 2008, prosecutors at the International Criminal Court (ICC), filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir: three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The ICC's prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity.

On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan as the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I concluded that his position as head of state does not grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC. The warrant was for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It did not include the crime of genocide because the majority of the Chamber did not find that the prosecutors had provided enough evidence to include such a charge.

Genocide in history

The preamble to the CPPCG states that "genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world," and that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity."

In many cases where accusations of genocide have circulated, partisans have fiercely disputed such an interpretation and the details of the event. This often leads to the promotion of vastly different versions of the event in question.

Revisionist attempts to deny or challenge claims of genocides are illegal in some countries. For example, several European countries ban denying the Holocaust, whilst in Turkey it is illegal to refer to mass killings of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians by the Ottoman Empire towards the end of the First World War as a genocide.

Stages of genocide, influences leading to genocide, and efforts to prevent it

In 1996 Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, presented a briefing paper called "The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State. In it he suggested that genocide develops in eight stages that are "predictable but not inexorable".

The Stanton paper was presented at the State Department, shortly after the Rwanda genocide and much of the analysis is based on why that genocide occurred. The preventative measures suggested, given the original target audience, were those that the United States could implement directly or use their influence on other governments to have implemented.

| ! Stage | ! Characteristics | ! Preventive measures |

| ! 1.Classification | People are divided into "us and them". | |

| ! 2.Symbolization | "When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups..." | "To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden as can hate speech". |

| ! 3.Dehumanization | "One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases." | "Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable. Leaders who incite genocide should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen." |

| ! 4.Organization | "Genocide is always organized... Special army units or militias are often trained and armed..." | "The U.N. should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations" |

| ! 5.Polarization | "Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda..." | "Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups...Coups d’état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions." |

| ! 6.Preparation | "Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity..." | "At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. ..." |

| ! 7.Extermination | "It is "extermination" to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human." | "At this stage, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection." |

| Genocide denial>Denial | "The perpetrators... deny that they committed any crimes..." | "The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts" |

In a paper for the Social Science Research Council Dirk Moses criticises the Stanton approach concluding:

Other authors have focused on the structural conditions leading up to genocide and the psychological and social processes that create an evolution toward genocide. Helen Fein showed that pre-existing anti-Semitism and systems that maintained anti-Semitic policies was related the number of Jews killed in different European countries during the Holocaust. Ervin Staub showed that economic deterioration and political confusion and disorganization were starting points of increasing discrimination and violence in many instances of genocides and mass killing. They lead to scapegoating a group and ideologies that identified that group as an enemy. A history of devaluation of the group that becomes the victim, past violence against the group that becomes the perpetrator leading to psychological wounds, authoritarian cultures and political systems, and the passivity of internal and external witnesses (bystanders) all contribute to the probability that the violence develops into genocide. Intense conflict between groups that is unresolved, becomes intractable and violent can also lead to genocide. The conditions that lead to genocide provide guidance to early prevention, such as humanizing a devalued group,creating ideologies that embrace all groups, and activating bystander responses. There is substantial research to indicate how this can be done, but information is only slowly transformed into action.

Cultural genocide

The precise definition of "cultural genocide" remains unclear. The term was proposed by lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1933 as a component to genocide, which he called "vandalism". The drafters of the 1948 Genocide Convention considered the use of the term, but dropped it under strong opposition from western countries, especially the United Kingdom, who feared that too broad a definition of genocide could implicate its activity in its colonies.

See also

Research:

Notes

References

Further reading

Articles

Books

Overviews

Resources

Research Programs

External links

Category:Crimes * Category:International criminal law Category:Population Category:United Nations General Assembly resolutions

af:Volksmoord als:Völkermord ang:Folcmorðor ar:إبادة جماعية az:Soyqırım be:Генацыд be-x-old:Генацыд bs:Genocid br:Gouennlazh bg:Геноцид ca:Genocidi cv:Геноцид cs:Genocida cy:Hil-laddiad da:Folkedrab de:Völkermord et:Genotsiid el:Γενοκτονία es:Genocidio eo:Genocido eu:Genozidio fa:نسلکشی fr:Génocide ga:Cinedhíothú gl:Xenocidio ko:집단 학살 hy:Ցեղասպանություն hr:Genocid id:Genosida it:Genocidio he:רצח עם jv:Genosida ka:გენოციდი kk:Геноцид sw:Mauaji ya kimbari ku:Jenosîd la:Generis occidio lv:Genocīds lt:Genocidas hu:Népirtás ms:Pembasmian kaum nl:Genocide ja:ジェノサイド no:Folkemord nn:Folkemord oc:Genocidi pl:Ludobójstwo pt:Genocídio ro:Genocid ru:Геноцид sq:Gjenocidi si:වර්ග සංහාරය simple:Genocide sk:Genocída (právo) sl:Genocid ckb:جینۆساید sr:Геноцид sh:Genocid fi:Kansanmurha sv:Folkmord tl:Pagpatay ng lahi ta:இனப்படுகொலை th:พันธุฆาต tr:Soykırım uk:Геноцид vi:Diệt chủng wa:Djenocide yi:פעלקער מארד zh:种族灭绝This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.