- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Arabs

http://wn.com/Arabs -

Bahrani people

The Bahrani (plural Baharna, ) are the indigenous Shi'a inhabitants of the archipelago of Bahrain and the oasis of Qatif on the Persian Gulf coast of Saudi Arabia (see historical region of Bahrain). The term is sometimes also extended to the Shi'a inhabitants of the al-Hasa oasis. They are ethnic Arabs, and some claim descent from Arab tribes. Their dialect of Arabic is known as "Bahrani" or "Bahrani Arabic," and they are overwhelmingly adherents of Twelver Shi'a Islam. Most Bahrani clerics have since the 18th century followed the conservative Akhbari school.

http://wn.com/Bahrani_people -

Hassan Massoudy

Hassan Massoudy (حسن المسعود الخطاط) is an Iraqi calligrapher who has published many collections of his work.He was born in 1944, in Najaf and currently lives in Paris, France.

http://wn.com/Hassan_Massoudy -

Hui people

The Hui people (, Xiao'erjing: حُوِ ذَو ) are an ethnic group in China, typically distinguished by their practice of Islam, and many of whom are direct descendants of Silk Road travelers.

http://wn.com/Hui_people -

Lakhmids

The Lakhmids (Arabic: ), Banu Lakhm (Arabic: ), Muntherids (Arabic: ), were a group of Arab Christians who lived in Southern Iraq, and made al-Hirah their capital in 266. Poets described it as a Paradise on earth, an Arab Poet described the city's pleasant climate and beauty "One day in al-Hirah is better than a year of treatment". The al-Hirah ruins are located 3 kilometers south of Kufa, on the west bank of the Euphrates.

http://wn.com/Lakhmids -

Malayali

The Malayali people (also spelled Malayalee; ; ; plural: Malayalikal) are a group of people who speak Malayalam, originating from the Indian state of Kerala. The Malayali identity is primarily linguistic, although in recent times the definition has been broadened to include emigrants of Malayali descent who partly maintain Malayali cultural traditions, even if they do not regularly speak the language. While the majority of Malayalis belong to Kerala, significant populations also exist in other parts of India, the Middle East, Europe and North America. According to the Indian census of 2001, there were 30,803,747 speakers of Malayalam in Kerala, making up 96.7% of the total population of that state. Hence the word Keralite is often used in the same context, though a proper definition is ambiguous.

http://wn.com/Malayali -

Mandaean

http://wn.com/Mandaean -

Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews or Mizrahim, (), also referred to as Edot HaMizrach (Communities of the East; Mizrahi Hebrew: ʿEdoth HamMizraḥ) are Jews descended from the Jewish communities of the Middle East, North Africa and the Caucasus. The term Mizrahi is used in Israel in the language of politics, media and some social scientists for Jews from the Arab world and adjacent, primarily Muslim-majority countries. This includes Jews from Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Morocco, Tunisia , Algeria, Kurdish areas, the eastern Caucasus, Georgia and Ethiopia. It would also include the Jews of India, Pakistan, and Baghdadi Jews who settled in those nations in the last few centuries (in contrast to Jewish communities of the Indian subcontinent established millennia earlier).

http://wn.com/Mizrahi_Jews -

Nabataean

http://wn.com/Nabataean -

Ottoman Empire

The Sublime Ottoman State (Ottoman Turkish, Persian: دَوْلَتِ عَلِيّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه Devlet-i ʿAliyye-yi ʿOsmâniyye, Modern Turkish: Yüce Osmanlı Devleti or Osmanlı İmparatorluğu) was an empire that lasted from 1299 to 1923.

http://wn.com/Ottoman_Empire -

Qaddafi

http://wn.com/Qaddafi -

Sibawayh

Abū Bishr ʻAmr ibn ʻUthmān ibn Qanbar Al-Bishrī (aka:Sībawayh) (Sibuyeh in Persian, سيبويه Sībawayh in Arabic, سیبویه) was a linguist of Persian origin born ca. 760 in the town of Bayza (ancient Nesayak) in the Fars province of Iran, died in Shiraz, also in the Fars, around .

http://wn.com/Sibawayh -

Tianjin

(; ; Postal map spelling: Tientsin) is a metropolis in Northeastern China and one of the five national central cities. It is governed as a direct-controlled municipality, one of four such designations, and is thus under direct administration of the central government, and borders Hebei Province and Beijing Municipality, bounded to the east by the Bohai Gulf portion of the Yellow Sea. In terms of urban population, it is the sixth largest city of the People's Republic of China, and its urban land area ranks 5th in the nation, only after Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen.

http://wn.com/Tianjin

-

Afghanistan

{{Infobox country

http://wn.com/Afghanistan -

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Arabic name given to a nation in the parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims (given the generic name of Moors), at various times in the period between 711 and 1492.

http://wn.com/Al-Andalus -

Al-Hasa

:This article refers to the traditional region of Al-Ahsa. For the current Saudi Arabian administrative unit sometimes called Al-Hasa, see: Al-Ahsa Governorate. For other uses see Al-Ahsa.

http://wn.com/Al-Hasa -

Algeria

Algeria (Arabic: , al-Jazā’ir, Berber: Dzayer, French: Algérie), officially the '''People's Democratic Republic of Algeria (also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria'''), is a country in North Africa. In terms of land area, it is the largest country on the Mediterranean Sea, the second largest on the African continent after Sudan, and the eleventh-largest country in the world.

http://wn.com/Algeria -

Arab League

{{Infobox Country

http://wn.com/Arab_League -

Arab states

http://wn.com/Arab_states -

Bahrain

Bahrain, officially Kingdom of Bahrain (, , literally: "Kingdom of the Two Seas"), is a small island country in the Persian Gulf ruled by the Al Khalifa royal family. While Bahrain is an archipelago of thirty-three islands, the largest (Bahrain Island) is long by wide. Saudi Arabia lies to the west and is connected to Bahrain via the King Fahd Causeway, which was officially opened on 25 November 1986. Qatar is to the southeast across the Gulf of Bahrain.

http://wn.com/Bahrain -

Bushehr Province

Bushehr or Bushire (Persian:استان بوشهر) is one of the 30 provinces of Iran. It is in the south of the country, with a long coastline onto the Persian Gulf. Its center is Bandar-e-Bushehr, the provincial capital. The province has nine counties: Bushehr, Dashtestan, Dashti, Dayyer, Deylam, Jam, Kangan, Ganaveh and Tangestan. In 2005, the province had a population of approximately 816,115 people.

http://wn.com/Bushehr_Province -

Cairo

Cairo (; , literally "The Vanquisher" or "The Conqueror") is the capital of Egypt, the largest city in Africa and the Arab World, and one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a center of the region's political and cultural life. Even before Cairo was established in the 10th century, the land composing the present-day city was the site of national capitals whose remnants remain visible in parts of Old Cairo. Cairo is also associated with Ancient Egypt due to its proximity to the Great Sphinx and the pyramids in adjacent Giza.

http://wn.com/Cairo -

Cyprus

Cyprus (; , Kýpros, ; ), – officially the Republic of Cyprus (, Kypriakī́ Dīmokratía, ; ) – is a Eurasian island country in the Eastern Mediterranean, south of Turkey and west of Syria and Lebanon. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of its most popular tourist destinations. An advanced, high-income economy with a very high Human Development Index, the Republic of Cyprus was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement until it joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.

http://wn.com/Cyprus -

Djibouti

Djibouti ( Jībūtī), officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Eritrea in the north, Ethiopia in the west and south, and Somalia in the southeast. The remainder of the border is formed by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

http://wn.com/Djibouti -

Egypt

Egypt (; , Miṣr, ; Egyptian Arabic: مصر, Maṣr, ; Coptic: , ; Greek: Αίγυπτος, Aiguptos; Egyptian:

http://wn.com/Egypt -

Eritrea

Eritrea ( or ; Ge'ez: , Arabic: إرتريا Iritrīyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the North East of Africa. The capital is Asmara. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast. The east and northeast of the country have an extensive coastline on the Red Sea, directly across from Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The Dahlak Archipelago and several of the Hanish Islands are part of Eritrea. Its size is just under with an estimated population of 5 million.

http://wn.com/Eritrea -

Ethiopia

{{Infobox country

http://wn.com/Ethiopia -

Hormozgan Province

http://wn.com/Hormozgan_Province -

Iberian peninsula

http://wn.com/Iberian_peninsula -

Iran

Iran ( ), officially the Islamic Republic of Iran is a country in Central Eurasia and Western Asia. The name Iran has been in use natively since the Sassanian era and came into use internationally in 1935, before which the country was also known to the western world as Persia. Both Persia and Iran are used interchangeably in cultural contexts; however, Iran is the name used officially in political contexts.

http://wn.com/Iran -

Iraq

Iraq ( or , Arabic: ), officially the Republic of Iraq (Arabic:

http://wn.com/Iraq -

Israel

Israel (, ''Yisrā'el; , Isrā'īl), officially the State of Israel (Hebrew: , Medīnat Yisrā'el; , Dawlat Isrā'īl''), is a parliamentary republic in the Middle East located on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. It borders Lebanon in the north, Syria in the northeast, Jordan and the West Bank in the east, Egypt and Gaza on the southwest, and contains geographically diverse features within its relatively small area. Israel is the world's only predominantly Jewish state, and is defined as A Jewish and Democratic State by the Israeli government.

http://wn.com/Israel -

Italy

Italy (; ), officially the Italian Republic (), is a country located in south-central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia along the Alps. To the south it consists of the entirety of the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Sardinia — the two largest islands in the Mediterranean Sea — and many other smaller islands. The independent states of San Marino and the Vatican City are enclaves within Italy, whilst Campione d'Italia is an Italian exclave in Switzerland. The territory of Italy covers some and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With 60.4 million inhabitants, it is the sixth most populous country in Europe, and the twenty-third most populous in the world.

http://wn.com/Italy -

Jordan

{{Infobox Country

http://wn.com/Jordan -

Khuzestan Province

http://wn.com/Khuzestan_Province -

Kuwait

The State of Kuwait (, Dawlat al-Kuwayt) is a sovereign Arab nation situated in the northeast of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the south, and Iraq to the north. It lies on the northwestern shore of the Persian Gulf. The name Kuwait is derived from the Arabic "akwat", the plural of "kout", meaning fortress built near water. The emirate covers an area of 17,820 square kilometres (6,880 sq mi) and has a population of about 2.7 million.

http://wn.com/Kuwait -

Lebanon

Lebanon ( or ; ; ), officially the Republic of Lebanon (Arabic: ; French: ), is a country on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered by Syria to the north and east, and Israel to the south. Lebanon's location at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian hinterland has dictated its rich history, and shaped a cultural identity of religious and ethnic diversity.

http://wn.com/Lebanon -

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library of the United States Congress, de facto national library of the United States, and the oldest federal cultural institution in the United States. Located in three buildings in Washington, D.C., it is the largest library in the world by shelf space and number of books. The head of the Library is the Librarian of Congress, currently James H. Billington.

http://wn.com/Library_of_Congress -

Libya

Libya ( ; Libyan vernacular: Lībya ; Amazigh: ), officially the '''Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya ( , also translated as Socialist People's Libyan Arab Great Jamahiriya'''), is a country located in North Africa. Bordering the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Libya lies between Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west.

http://wn.com/Libya -

Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali (), is a landlocked country in Western Africa. Mali borders Algeria on the north, Niger on the east, Burkina Faso and the Côte d'Ivoire on the south, Guinea on the south-west, and Senegal and Mauritania on the west. Its size is just over 1,240,000 km² with a population more than 14 million. Its capital is Bamako.

http://wn.com/Mali -

Malta

Malta , officially the Republic of Malta (), is a southern European country and consists of an archipelago situated centrally in the Mediterranean, 93 km south of Sicily and 288 km east of Tunisia, with the Strait of Gibraltar 1,826 km to the west and Alexandria 1,510 km to the east.

http://wn.com/Malta -

Mauritania

Mauritania ( Mūrītāniyā; ; Soninke: Murutaane; Pulaar: Moritani; ), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a country in North Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean in the west, by Western Sahara in the north, by Algeria in the northeast, by Mali in the east and southeast, and by Senegal in the southwest. It is named after the Roman province of Mauretania, even though the modern state covers a territory far to the southwest of the old province. The capital and largest city is Nouakchott, located on the Atlantic coast.

http://wn.com/Mauritania -

Mecca

Mecca (), also spelled Makkah (occasionally 'Bakkah') (; Makkah and in full: transliterated Makkah Al Mukarramah ) is a city in Saudi Arabia, and the holiest meeting site in Islam, closely followed by Medina.

http://wn.com/Mecca -

Medina

Medina (; , , or المدينة ; also transliterated as Madinah; officially al-Madīnah al-Munawwarah (the radiant city)) is a city in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia, and serves as the capital of the Al Madinah Province. It is the second holiest city in Islam, and the burial place of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and it is historically significant for being his home after the Hijrah.

http://wn.com/Medina -

Morocco

Morocco (, al-Maġrib; Berber: Amerruk / Murakuc; French: Maroc), officially the Kingdom of Morocco (المملكة المغربية, al-Mamlakah al-Maġribiyya), is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of nearly 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², including the disputed Western Sahara which is mainly under Moroccan administration. Morocco has a coast on the Atlantic Ocean that reaches past the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered by Spain to the north (a water border through the Strait and land borders with three small Spanish-controlled exclaves, Ceuta, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera), Algeria to the east, and Mauritania to the south.

http://wn.com/Morocco -

Niger

Niger ( or ; ), officially named the Republic of Niger, is a landlocked country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east. Niger covers a land area of almost 1,270,000 km2, over 80 percent of which is covered by the Sahara desert. The country's predominantly Islamic population of just above 15,000,000 is mostly clustered in the far south and west of the nation. The capital city is Niamey.

http://wn.com/Niger -

Ningbo

Ningbo (; literally "Tranquil Waves"; previous name: 明州 Mingzhou) is a seaport with sub-provincial administrative status. The city has a population of 2,201,000 and is located on the northeastern of Zhejiang province, China. Lying south of the Hangzhou Bay, and facing the East China Sea to the east, Ningbo borders Shaoxing to the west and Taizhou to the south, and is separated from Zhoushan by a narrow body of water.

http://wn.com/Ningbo -

Oman

Oman (pronounced ; '), officially the Sultanate of Oman''' ( ), is an Arab country in southwest Asia on the southeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula. It borders the United Arab Emirates on the northwest, Saudi Arabia on the west and Yemen on the southwest. The coast is formed by the Arabian Sea on the southeast and the Gulf of Oman on the northeast. The country also contains Madha and Musandam, two exclaves on the Gulf of Oman, south of the Strait of Hormuz and surrounded by the United Arab Emirates on the land side.

http://wn.com/Oman -

Qatar

Qatar ( ; ; local pronunciation: ), also known as the State of Qatar or locally , is an Arab country, known officially as an emirate, in the Middle East, occupying the small Qatar Peninsula on the northeasterly coast of the much larger Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the south; otherwise, the Persian Gulf surrounds the state. A strait of the Persian Gulf separates Qatar from the nearby island nation of Bahrain.

http://wn.com/Qatar -

Sana

http://wn.com/Sana -

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (), commonly known as Saudi Arabia, occasionally spelled '''Sa'udi Arabia''', is the largest Arab country of the Middle East. It is bordered by Jordan and Iraq on the north and northeast, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates on the east, Oman on the southeast, and Yemen on the south. The Persian Gulf lies to the northeast and the Red Sea to its west. It has an estimated population of 28 million, and its size is approximately . The kingdom is sometimes called "The Land of the Two Holy Mosques" in reference to Mecca and Medina, the two holiest places in Islam. The two mosques are Masjid al-Haram (in Mecca) and Masjid Al-Nabawi (in Medina). The current kingdom was founded by Abdul-Aziz bin Saud, whose efforts began in 1902 when he captured the Al-Saud’s ancestral home of Riyadh, and culminated in 1932 with the proclamation and recognition of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, though its national origins go back as far as 1744 with the establishment of the First Saudi State. Saudi Arabia's government takes the form of an Islamic absolute monarchy. Human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have repeatedly expressed concern about the state of human rights in Saudi Arabia.

http://wn.com/Saudi_Arabia -

Sinai

http://wn.com/Sinai -

Somalia

Somalia ( ; ; ), officially the Republic of Somalia (, ) and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic under communist rule, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, the Gulf of Aden with Yemen to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, and Ethiopia to the west. With the longest coastline on the continent, its terrain consists mainly of plateaus, plains and highlands.

http://wn.com/Somalia -

Spain

Spain ( ; , ), officially the Kingdom of Spain (), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Its mainland is bordered to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea except for a small land boundary with the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar; to the north by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay; and to the northwest and west by the Atlantic Ocean and Portugal.

http://wn.com/Spain -

Sudan

Sudan (), officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in northeastern Africa. It is the largest country in Africa and the Arab world, and tenth largest in the world by area. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east,Kenya and Uganda to the southeast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya to the northwest. The world's longest river, the Nile, divides the country between east and west sides.

http://wn.com/Sudan -

Syria

Syria ( ; ' or '), officially the Syrian Arab Republic (), is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest.

http://wn.com/Syria -

Tajikistan

Tajikistan ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Tajikistan (, Jumhurii Tojikiston; , Respublika Tadzhikistan; Jomhuri-ye Tajikestan), is a mountainous landlocked country in Central Asia. Afghanistan borders it to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and People's Republic of China to the east. Tajikistan also lies adjacent to Pakistan and the Gilgit-Baltistan region, separated by the narrow Wakhan Corridor.

http://wn.com/Tajikistan -

Tianjin

(; ; Postal map spelling: Tientsin) is a metropolis in Northeastern China and one of the five national central cities. It is governed as a direct-controlled municipality, one of four such designations, and is thus under direct administration of the central government, and borders Hebei Province and Beijing Municipality, bounded to the east by the Bohai Gulf portion of the Yellow Sea. In terms of urban population, it is the sixth largest city of the People's Republic of China, and its urban land area ranks 5th in the nation, only after Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen.

http://wn.com/Tianjin -

Tunisia

Tunisia (pronounced , ; Tūnis), officially the Tunisian Republic ( al-Jumhūriyya at-Tūnisiyya), is the northernmost country in Africa. It is an Arab country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area is almost 165,000 km², with an estimated population of just over 10.3 million. Its name is derived from the capital Tunis located in the north-east.

http://wn.com/Tunisia -

Turkey

Turkey (), known officially as the Republic of Turkey (), is a Eurasian country that stretches across the Anatolian peninsula in western Asia and Thrace in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe. Turkey is one of the six independent Turkic states. Turkey is bordered by eight countries: Bulgaria to the northwest; Greece to the west; Georgia to the northeast; Armenia, Azerbaijan (the exclave of Nakhchivan) and Iran to the east; and Iraq and Syria to the southeast. The Mediterranean Sea and Cyprus are to the south; the Aegean Sea to the west; and the Black Sea is to the north. The Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles (which together form the Turkish Straits) demarcate the boundary between Eastern Thrace and Anatolia; they also separate Europe and Asia.

http://wn.com/Turkey -

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) (, , short name: The Emirates, local short name: Al Emarat الامارات) is a federation situated in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula in Southwest Asia on the Persian Gulf, bordering Oman and Saudi Arabia and sharing sea borders with Iraq, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Iran. The UAE consists of seven states, termed emirates, (because they are ruled by Emirs) which are Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm al-Quwain, Ras al-Khaimah and Fujairah. The capital and second largest city of the United Arab Emirates is Abu Dhabi. It is also the country's center of political, industrial, and cultural activities.

http://wn.com/United_Arab_Emirates -

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan, officially the Republic of Uzbekistan (‘zbekiston Respublikasi'' or Ўзбекистон Республикаси) is one of the six independent Turkic states. It is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia, formerly part of the Soviet Union. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south.

http://wn.com/Uzbekistan -

Western Sahara

Western Sahara (Arabic: الصحراء الغربية, Berber: Taneẓṛuft Tutrimt, ) is a disputed territory in North Africa, bordered by Morocco to the north, Algeria to the northeast, Mauritania to the east and south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Its surface area amounts to . It is one of the most sparsely populated territories in the world, mainly consisting of desert flatlands. The population of the territory is estimated at just over 500,000, over half of whom live in El Aaiun, the largest city in Western Sahara.

http://wn.com/Western_Sahara -

Yemen

Yemen (Arabic: اليَمَن al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen (Arabic: الجمهورية اليمنية al-Jumhuuriyya al-Yamaniyya) is a country located on the Arabian Peninsula in Southwest Asia. It has an estimated population of more than 23 million people and is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Aden to the south, and Oman to the east.

http://wn.com/Yemen

- abjad

- accusative case

- Adjective

- affricate

- Afghanistan

- African Union

- Akkadian

- Al-Andalus

- Al-Hasa

- alchemy

- alcohol

- algebra

- Algeria

- Algerian Arabic

- alkali

- Allah

- allophone

- Alveolar consonant

- Amharic language

- Andalusi Arabic

- Arab League

- Arab states

- Arab world

- Arabia

- Arabian peninsula

- Arabic alphabet

- Arabic chat alphabet

- Arabic diacritics

- Arabic grammar

- Arabic literature

- Arabist

- Arabs

- ArabTeX

- Aramaic alphabet

- Aramaic language

- ayah

- Bahrain

- Bahraini Arabic

- Bahrani Arabic

- Bahrani people

- Bahá'í orthography

- Baluchi language

- Bedouin

- Bengali language

- Berber languages

- broken plural

- Bushehr Province

- Cairo

- calque

- cardinal number

- Catalan language

- causative

- Central Asian Arabic

- Charles Ferguson

- Chinese languages

- Classical Arabic

- Classical Hebrew

- clitic

- Code-switching

- construct state

- Coptic alphabet

- coronal consonant

- cotton

- Croatian language

- Cypriot Arabic

- Cyprus

- Cyrillic alphabet

- darija

- denominative verb

- Dental consonant

- diacritic

- dialect chain

- diglossia

- DIN 31635

- diphthongs

- Djibouti

- Egypt

- Egyptian Arabic

- elative

- elementary school

- elision

- emphatic consonant

- enclitic

- energetic mood

- English language

- epiglottal consonant

- epigraphic

- Eritrea

- Ethiopia

- extemporaneous

- first language

- Foreign Languages

- French Algeria

- French language

- fricative

- Fricative consonant

- future tense

- Garshuni

- Ge'ez language

- Ge'ez script

- gemination

- gender (grammar)

- genitive case

- German language

- gerund

- Ghassanids

- Glossary of Islam

- Glottal consonant

- glottal stop

- Grammatical aspect

- grammatical mood

- grammatical number

- Grammatical tense

- grammatical voice

- Greek alphabet

- Greek language

- Gujarati language

- Gulf Arabic

- Hadith

- hamza

- handwriting

- Hassan Massoudy

- Hassaniya Arabic

- Hausa language

- heavy syllable

- Hebrew language

- Hejazi Arabic

- hiatus (linguistics)

- Hijaz

- Hindi

- Hindi language

- Hindustani language

- Hormozgan Province

- Hui people

- Iberian peninsula

- imperative mood

- imperfective

- indicative

- Indonesian language

- infinitive

- instant messaging

- intensive

- Internet

- Internet Relay Chat

- IPA

- Iran

- Iraq

- Iraqi Arabic

- Irrealis mood

- Islam

- Islamic world

- ISO 233

- ISO 233-2

- Israel

- Italian language

- Italy

- Jordan

- Jussive mood

- Kabyle language

- Kanuri language

- Khuzestan Province

- Kindite

- Kinubi

- koine

- Kurdish language

- Kuwait

- Kuwaiti Arabic

- Labial consonant

- labialization

- Lakhmids

- language school

- Latin script

- Lebanese Arabic

- Lebanon

- Levant

- Levantine Arabic

- Library of Congress

- Libya

- Libyan Arabic

- Lihyanite

- List of arabophones

- Literary Arabic

- literary language

- liturgical language

- loan translation

- loanword

- low vowel

- macrolanguage

- Maghreb

- Maghrebi Arabic

- makhzen

- Malay language

- Malayali

- Mali

- Malta

- Maltese alphabet

- Maltese language

- Mandaean

- Mauritania

- Mecca

- Medina

- Mediterranean

- Mehri language

- Middle Ages

- Middle East

- Middle Persian

- Milanese language

- Mizrahi Jews

- monophthongization

- morae

- Moroccan Arabic

- Morocco

- Muslim world

- Muslims

- Nabataean

- Nabataean language

- Nabatean alphabet

- nadir

- Najdi Arabic

- Nasal consonant

- Naskh (script)

- Neapolitan language

- Niger

- Ningbo

- nisba

- nominative case

- non-past

- North Africa

- noun case

- nunation

- Old North Arabian

- Oman

- Ottoman Empire

- Palatal consonant

- Panthay Rebellion

- Parthian

- participle

- Pashto language

- past

- pausa

- perfective

- Persian language

- personal computers

- pharyngeal consonant

- pharyngealization

- phoneme

- phonology

- placeholder

- Portuguese language

- positional notation

- Pre-Islamic Arabia

- prefix

- Pronoun

- Proto-Human language

- proto-language

- Proto-Semitic

- proverb

- Punjabi language

- Qaddafi

- Qatar

- Qur'an

- Quran

- Quranic Arabic

- reflexive

- religious studies

- right-to-left

- Rohingya language

- Roman Catholic

- Romance languages

- root (linguistics)

- Ruq'ah

- Russian language

- Safaitic

- Saharan Arabic

- salat

- Sana

- Saraiki language

- Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabic

- secondary school

- Semitic language

- Semitic languages

- Semitic root

- Serbian language

- Sibawayh

- Sicilian language

- Sicily

- Siculo Arabic

- Siculo-Arabic

- Sinai

- Sindhi language

- soap opera

- Somali language

- Somalia

- sonority hierarchy

- sound plural

- Spain

- Spanish language

- Status constructus

- Stop consonant

- subjunctive

- Sudan

- Sudanese Arabic

- suffix

- sugar

- Sulayyil

- superheavy syllable

- Swahili language

- syllabic consonant

- Syria

- Syriac

- Syriac alphabet

- Tagalog language

- Tajikistan

- talk show

- Tamil language

- tanwīn

- Thamud

- Thamudic

- Tianjin

- Tigrinya language

- transcription

- transliteration

- triliteral

- Trill consonant

- Tunisia

- Tunisian Arabic

- Turkey

- Turkish language

- tāʾ marbūṭa

- United Arab Emirates

- Urdu

- Urdu language

- Uvular consonant

- Uyghur language

- Uzbekistan

- varieties of Arabic

- Varieties_of_Arabic

- Velar consonant

- velarization

- verb conjugation

- verbal noun

- voice (phonetics)

- voiceless

- vowel harmony

- vowel length

- Western Sahara

- World Wide Web

- Yemen

- Yemeni Arabic

- zaouia

- zenith

- ʾIʿrab

- ء

- ج

- غ

- ق

- ك

- ي

- گ

- ݣ

- Ḍād

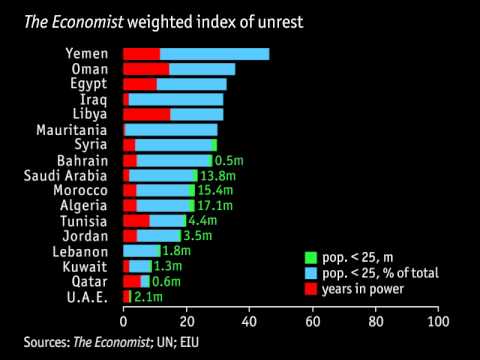

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:22

- Published: 21 Feb 2011

- Uploaded: 03 Jan 2012

- Author: EconomistMagazine

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:50

- Published: 18 Aug 2011

- Uploaded: 26 Dec 2011

- Author: AlJazeeraEnglish

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:56

- Published: 05 Jan 2012

- Uploaded: 06 Jan 2012

- Author: TheAlyonaShow

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 25:46

- Published: 25 Feb 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Dec 2011

- Author: RussiaToday

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 11:00

- Published: 01 May 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Dec 2011

- Author: RussiaToday

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 23:43

- Published: 07 Feb 2011

- Uploaded: 04 Jan 2012

- Author: AlJazeeraEnglish

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:05

- Published: 01 Aug 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Dec 2011

- Author: AssociatedPress

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 27:03

- Published: 24 Jul 2011

- Uploaded: 02 Jan 2012

- Author: AlJazeeraEnglish

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 25:05

- Published: 30 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 18 Dec 2011

- Author: AlJazeeraEnglish

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:17

- Published: 25 Jun 2011

- Uploaded: 14 Dec 2011

- Author: TheAlyonaShow

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 35:04

- Published: 05 Jun 2011

- Uploaded: 30 Oct 2011

- Author: OsloFreedomForum

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:53

- Published: 13 Aug 2011

- Uploaded: 04 Jan 2012

- Author: MrWissamAlrawi

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 47:20

- Published: 21 May 2011

- Uploaded: 04 Jan 2012

- Author: AlJazeeraEnglish

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 11:29

- Published: 26 Jul 2010

- Uploaded: 04 Jan 2012

- Author: RussiaToday

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 41:36

- Published: 19 Feb 2011

- Uploaded: 05 Jan 2012

- Author: mangoscotland

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 8:32

- Published: 30 Jul 2007

- Uploaded: 05 Jan 2012

- Author: naserazeez

![Revolution in the Arab World ... TUNISIA... EGYPT... and Beyond [3/3] Revolution in the Arab World ... TUNISIA... EGYPT... and Beyond [3/3]](http://web.archive.org./web/20120107112607im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/23IYEsLAECM/0.jpg)

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 31:24

- Published: 17 Feb 2011

- Uploaded: 01 Sep 2011

- Author: LeftStreamed

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:03

- Published: 10 Nov 2011

- Uploaded: 16 Nov 2011

- Author: shazyboy259

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:51

- Published: 28 Jan 2011

- Uploaded: 09 Dec 2011

- Author: AssociatedPress

size: 3.2Kb

size: 5.3Kb

size: 14.5Kb

- Abbasid Caliphate

- abjad

- accusative case

- Adjective

- affricate

- Afghanistan

- African Union

- Akkadian

- Al-Andalus

- Al-Hasa

- alchemy

- alcohol

- algebra

- Algeria

- Algerian Arabic

- alkali

- Allah

- allophone

- Alveolar consonant

- Amharic language

- Andalusi Arabic

- Arab League

- Arab states

- Arab world

- Arabia

- Arabian peninsula

- Arabic alphabet

- Arabic chat alphabet

- Arabic diacritics

- Arabic grammar

- Arabic literature

- Arabist

- Arabs

- ArabTeX

- Aramaic alphabet

- Aramaic language

- ayah

- Bahrain

- Bahraini Arabic

- Bahrani Arabic

- Bahrani people

- Bahá'í orthography

- Baluchi language

- Bedouin

- Bengali language

- Berber languages

- broken plural

- Bushehr Province

- Cairo

- calque

- cardinal number

- Catalan language

- causative

- Central Asian Arabic

- Charles Ferguson

- Chinese languages

- Classical Arabic

- Classical Hebrew

- clitic

- Code-switching

size: 1.7Kb

size: 2.0Kb

size: 2.1Kb

size: 12.2Kb

size: 0.7Kb

size: 2.1Kb

size: 7.2Kb

size: 0.9Kb

size: 7.1Kb

| Name | Arabic |

|---|---|

| Nativename | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Imagecaption | in written Arabic (Naskh script) |

| Region | Primarily in the Arab states of the Middle East and North Africa;liturgical language of Islam. |

| Speakers | More than 280 million native speakers |

| Familycolor | Afro-Asiatic |

| Fam2 | Semitic |

| Fam3 | Central Semitic |

| Stand1 | Modern Standard Arabic |

| Dia1 | Western (Maghrebi) |

| Dia2 | Central (incl. Egyptian) |

| Dia3 | Northern (incl. Levantine, Iraqi) |

| Dia4 | Southern (incl. Gulf, Hejazi, Yemeni) |

| Script | Arabic alphabet, Syriac alphabet (Garshuni) |

| Nation | Official language of 26 states, the third most after English and French |

| Agency | : Supreme Council of the Arabic language in Algeria : Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo : Iraqi Academy of Sciences : Jordan Academy of Arabic : Academy of the Arabic Language in Jamahiriya : Academy of the Arabic Language in Rabat : Academy of the Arabic Language in Mogadishu : Academy of the Arabic Language in Khartoum : Arab Academy of Damascus (the oldest) : Beit Al-Hikma Foundation : Academy of the Arabic Language in Israel |

| Iso1 | ar |

| Iso2 | ara |

| Lc1 | ara |ld1Arabic (generic)(see varieties of Arabic for the individual codes) |

| Ll1 | none |

| Map | Arabic Language.PNG |

| Mapcaption | Distribution of Arabic as an official language in the Arab World. Majority Arabic speakers (blue) and minority Arabic speakers (green). |

| Notice | IPA}} |

Many of the spoken varieties are mutually unintelligible, and the varieties as a whole constitute a macrolanguage. This means that on purely linguistic grounds they would likely be considered to constitute more than one language, but are commonly grouped together as a single language for political and/or ethnic reasons. If considered multiple languages, it is unclear how many languages there would be, as the spoken varieties form a dialect chain with no clear boundaries. If Arabic is considered a single language, it counts more than 200 million first language speakers (according to some estimates, as high as 280 million), more than that of any other Semitic language. If considered separate languages, the most-spoken variety would likely be Egyptian Arabic, with more than 50,000,000 native speakers — still greater than any other Semitic language.

The modern written language (Modern Standard Arabic) is derived from the language of the Quran (known as Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic). It is widely taught in schools, universities, and used to varying degrees in workplaces, government and the media. The two formal varieties are grouped together as Literary Arabic, which is the official language of 26 states and the liturgical language of Islam. Modern Standard Arabic largely follows the grammatical standards of Quranic Arabic and uses much of the same vocabulary. However, it has discarded some grammatical constructions and vocabulary that no longer have any counterpoint in the spoken varieties, and adopted certain new constructions and vocabulary from the spoken varieties. Much of the new vocabulary is used to denote concepts that have arisen in the post-Quranic era, especially in modern times.

Arabic is the only surviving member of the Old North Arabian dialect group, attested in Pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions dating back to the 4th century. Arabic is written with the Arabic alphabet, which is an abjad script, and is written from right-to-left.

Arabic has lent many words to other languages of the Islamic world, like Malay, Turkish, Urdu, Hausa, Hindi and Persian. During the Middle Ages, Literary Arabic was a major vehicle of culture in Europe, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy. As a result, many European languages have also borrowed many words from it. Arabic influence is seen in Mediterranean languages, particularly Spanish, Portuguese, and Sicilian, owing to both the proximity of European and Arab civilizations and 700 years of Arab rule in some parts of the Iberian peninsula (see Al-Andalus).

Arabic has also borrowed words from many languages, including Hebrew, Greek, Persian and Syriac in early centuries, Turkish in medieval times and contemporary European languages in modern times. However, the current tendency is to coin new words using the existing lexical resources of the language, or to repurpose old words, rather than directly borrowing foreign words.

Classical, Modern Standard, and spoken Arabic

Arabic usually designates one of three main variants: Classical Arabic; Modern Standard Arabic; colloquial or dialectal Arabic.Classical Arabic is the language found in the Qur'an and used from the period of Pre-Islamic Arabia to that of the Abbasid Caliphate. Theoretically, Classical Arabic is considered normative, according to the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh), and the vocabulary defined in classical dictionaries (such as the ). In practice, however, modern authors almost never write in pure Classical Arabic, instead using a literary language with its own grammatical norms and vocabulary, commonly known as Modern Standard Arabic. This is the variety used in most current, printed Arabic publications, spoken by some of the Arabic media across North Africa and the Middle East, and understood by most educated Arabic speakers. "Literary Arabic" and "Standard Arabic" ( ) are less strictly defined terms that may refer to Modern Standard Arabic or Classical Arabic.

Some of the differences between Classical Arabic (CA) and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) are as follows:

MSA uses much Classical vocabulary (e.g. "to go") that is not present in the spoken varieties. However, when multiple Classical synonyms are available, MSA tends to prefer words with cognates in the spoken varieties over words without cognates. In addition, MSA has borrowed or coined a large number of terms for concepts that did not exist in Quranic times (and in fact continues to evolve). Some words have been borrowed from other languages, notice that transliteration mainly indicates spelling not real pronunciation (e.g. "film" or "democracy"). However, the current preference is to avoid direct borrowings, preferring to either use loan translations (e.g. "branch", also used for the branch of a company or organization; "wing", also used for the wing of an airplane, building, air force, etc.) or to coin new words using existing lexical resources (e.g. "corporation", "socialism", both ultimately based on the verb "to share, partner with"; "university", based on "to gather, unite"; "republic", based on "multitude"). An earlier tendency was to re-purpose older words that had fallen into disuse (e.g. "telephone" < "invisible caller (in Sufism)"; "newspaper" < "palm-leaf stalk").

Colloquial or dialectal Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties which constitute the everyday spoken language. Colloquial Arabic has many different regional variants; these sometimes differ enough to be mutually unintelligible and some linguists consider them distinct languages. The varieties are typically unwritten. They are often used in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows, as well as occasionally in certain forms of written media, such as poetry and printed advertising. The only variety of modern Arabic to have acquired official language status is Maltese, spoken in (predominately Roman Catholic) Malta and written with the Latin script. It is descended from Classical Arabic through Siculo-Arabic and is not mutually intelligible with other varieties of Arabic. Most linguists list it as a separate language rather than as a dialect of Arabic. Historically, Algerian Arabic was taught in French Algeria under the name darija.

Note that even during Muhammad's lifetime, there were dialects of spoken Arabic. Muhammad spoke in the dialect of Mecca, in the western Arabian peninsula, and it was in this dialect that the Quran was written down. However, the dialects of the eastern Arabian peninsula were considered the most prestigious at the time, and so the language of the Quran was ultimately converted to follow the eastern phonology. It is this phonology that underlies the modern pronunciation of Classical Arabic. The phonological differences between these two dialects account for some of the complexities of Arabic writing, most notably the writing of the glottal stop or hamza (which was preserved in the eastern dialects but lost in western speech) and the use of (representing a sound preserved in the western dialects but merged with in eastern speech).

Language and dialect

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, which is the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their local dialect and their school-taught Standard Arabic. When educated Arabs of different dialects engage in conversation (for example, a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), many speakers code-switch back and forth between the dialectal and standard varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. Arabic speakers often improve their familiarity with other dialects via music or film.The issue of whether Arabic is one language or many languages is politically charged, similar to the issue with Chinese, Hindi and Urdu, Serbian and Croatian, etc. The issue of diglossia between spoken and written language is a significant complicating factor: A single written form, significantly different from any of the spoken varieties learned natively, unites a number of sometimes divergent spoken forms. For political reasons, Arabs mostly assert that they all speak a single language, despite significant issues of mutual incomprehensibility among differing spoken versions.

From a linguistic standpoint, it is often said that the various spoken varieties of Arabic differ among each other collectively about as much as the Romance languages. This is an apt comparison in a number of ways. The period of divergence from a single spoken form is similar—perhaps 1500 years for Arabic, 2000 years for the Romance languages. Also, a linguistically innovative variety such as Moroccan Arabic is essentially incomprehensible to all non-Moroccans other than Algerians and Tunisians, much as French is incomprehensible to Spanish or Italian speakers. However, there is some mutual comprehensibility between conservative varieties of Arabic even across significant geographical distances. This suggests that the spoken varieties, at least, should linguistically be considered separate languages.

On the other hand, a significant difference between Arabic and the Romance languages is that the latter also correspond to a number of different standard written varieties, each of which separately informs the related spoken varieties, while all spoken Arabic varieties share a single written language. Indeed, a similar situation exists with the Romance languages in the case of Italian. As spoken varieties, Milanese, Neapolitan and Sicilian (among others) are different enough to be largely mutually incomprehensible, yet since they share a single written form (Standard Italian), they are often said by Italians to be dialects of the same language. As in many similar cases, the extent to which the Italian varieties are locally considered dialects or separate languages depends to a large extent on political factors, which can change over time. Linguists are divided over whether and to what extent to incorporate such considerations when judging issues of language and dialect.

Influence of Arabic on other languages

The influence of Arabic has been most important in Islamic countries. Arabic is an important source of vocabulary for languages such as Baluchi, Bengali, Berber, Catalan, English, French, German, Gujarati, Hindustani, Italian, Indonesian, Kurdish, Malay, Malayali, Maltese, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Punjabi, Rohingya, Saraiki, Sindhi, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, Tagalog, Tamil, Turkish and Urdu as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken. For example, the Arabic word for book ( ) has been borrowed in all the languages listed, with the exception of French, Spanish, Italian, Catalan and Portuguese which use the Latin-derived words "livre", "libro", "llibre" and "livro", respectively, German and English which use the Germanic "Buch" and "Book", Tagalog which uses "aklat", Hebrew which uses "sefer", Gujarati which uses "chopdi", Marathi which uses "pustak" and Bengali which uses "boi".

In addition, English has many Arabic loan words, some directly but most through the medium of other Mediterranean languages. Examples of such words include admiral, adobe, alchemy, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, alkaline, almanac, amber, arsenal, assassin, banana, candy, carat, cipher, coffee, cotton, hazard, jar, jasmine, lemon, loofah, magazine, mattress, sherbet, sofa, sugar, sumac, tariff and many other words. Other languages such as Maltese and Kinubi derive from Arabic, rather than merely borrowing vocabulary or grammar rules.

The terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber "prayer" < salat) ( ), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq "logic"), economic items (like English sugar) to placeholders (like Spanish fulano "so-and-so") and everyday conjunctions (like Hindustani lekin "but", or Spanish hasta "until"). Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most Islamic religious terms are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as salat 'prayer' and imam 'prayer leader.' In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often transferred indirectly via other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic.

For example, most Arabic loanwords in Hindustani entered through Persian, and many older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri. Some words in English and other European languages are derived from Arabic, often through other European languages, especially Spanish and Italian. Among them are commonly used words like "sugar" (sukkar), "cotton" () and "magazine" (). English words more recognizably of Arabic origin include "algebra", "alcohol", "alchemy", "alkali", "zenith" and "nadir". Some words in common use, such as "intention" and "information", were originally calques of Arabic philosophical terms.

Arabic words also made their way into several West African languages as Islam spread across the Sahara. Variants of Arabic words such as kitaab (book) have spread to the languages of African groups who had no direct contact with Arab traders.

Arabic was influenced by other languages as well. The most important sources of borrowings into (pre-Islamic) Arabic are from the related (Semitic) languages Aramaic, which used to be the principal, international language of communication throughout the ancient Near and Middle East, Ethiopic, and to a lesser degree Hebrew (mainly religious concepts). In addition, a substantial number of cultural, religious and political terms that have entered Arabic was borrowed from Iranian, notably Middle Persian or Parthian, and to a lesser extent, (Classical) Persian.

As Arabic occupied a position similar to Latin (in Europe) throughout the Islamic world many of the Arabic concepts in the field of science, philosophy, commerce etc., were often coined by non-native Arabic speakers, notably by Aramaic and Persian translators. This process of using Arabic roots, notably in Turkish and Persian, to translate foreign concepts continued right until the 18th and 19th century, when large swaths of Arab-inhabited lands were under Ottoman rule.

Arabic and Islam

Classical Arabic is the language of the Qur'an. Arabic is closely associated with the religion of Islam because the Quran is written in the language, but it is nevertheless also spoken by Arab Christians, Mizrahi Jews and Iraqi Mandaeans. Most of the world's Muslims do not speak Arabic as their native language but many can read the Quranic script and recite the Qur'an. Among Non-Arab Muslims, translations of the Qur'an are most often accompanied by the original text.Some Muslims present a monogenesis of languages and claim that the Arabic language was the language revealed by God for the benefit of mankind and the original language as a prototype symbolic system of communication, based upon its system of triconsonantal roots, spoken by man from which all other languages were derived, having first been corrupted. Statements spread in later centuries regarding the Arabic language being the language of Paradise are not considered authentic according to the scholars of Hadith and are widely discredited.

History

The earliest surviving texts in Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, are the Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, from the 8th century BC, written not in the modern Arabic alphabet, nor in its Nabataean ancestor, but in variants of the epigraphic South Arabian musnad. These are followed by 6th-century BC Lihyanite texts from southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout Arabia and the Sinai, and not actually connected with Thamud. Later come the Safaitic inscriptions beginning in the 1st century BC, and the many Arabic personal names attested in Nabataean inscriptions (which are, however, written in Aramaic). From about the 2nd century BC, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Fāw (near Sulayyil) reveal a dialect which is no longer considered "Proto-Arabic", but Pre-Classical Arabic. By the fourth century AD, the Arab kingdoms of the Lakhmids in southern Iraq, the Ghassanids in southern Syria the Kindite Kingdom emerged in Central Arabia. Their courts were responsible for some notable examples of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, and for some of the few surviving pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions in the Arabic script.

Dialects and descendants

Colloquial Arabic is a collective term for the spoken varieties of Arabic used throughout the Arab world, which differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the varieties within and outside of the Arabian peninsula, followed by that between sedentary varieties and the much more conservative Bedouin varieties. All of the varieties outside of the Arabian peninsula (which include the large majority of speakers) have a large number of features in common with each other that are not found in Classical Arabic. This has led researchers to postulate the existence of a prestige koine dialect in the one or two centuries immediately following the Arab conquest, whose features eventually spread to all of the newly conquered areas. (These features are present to varying degrees inside the Arabian peninsula. Generally, the Arabian peninsula varieties have much more diversity than the non-peninsula varieties, but have been understudied.)Within the non-peninsula varieties, the largest difference is between the non-Egyptian North African dialects (especially Moroccan Arabic) and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is nearly incomprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Algeria (although the converse is not true, in part due to the popularity of Egyptian films and other media).

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided a significant number of new words, and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order; however, a much more significant factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine fīh, and North African kayən all mean "there is", and all come from Classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.

Examples

{| class=wikitable ! Variety ! I love reading a lot ! When I went to the library ! I only found this old book ! I wanted to read a book about the history of women in France. |- ! Classical Arabic (liturgical or poetic only) | | | | |- ! Modern Standard Arabic | | | | |- ! Moroccan | | | | |- ! Tunisian | | | | |- ! Egyptian | | | | |- ! Lebanese | | | | |- ! Iraqi | | | | |- ! Saudi | | | | |- ! Kuwaiti | | | | |}

Koine

According to Charles Ferguson, the following are some of the characteristic features of the koine that underlies all of the modern dialects outside the Arabian peninsula. Although many other features are common to most or all of these varieties (see varieties of Arabic), Ferguson believes that these features in particular are unlikely to have evolved independently more than once or twice, and together suggest the existence of the koine:

Dialect groups

The major dialect groups are:

Egyptian Arabic

Maghrebi Arabic

Maghrebi Arabic includes Moroccan Arabic, Algerian Arabic, Saharan Arabic, Tunisian Arabic, and Libyan Arabic, and is spoken by around 75 million North Africans in Morocco, Western Sahara, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Niger, and western Egypt; it is often difficult for speakers of Middle Eastern Arabic varieties to understand. The Berber influence in these dialects varies in degree.

Mesopotamian Arabic

Levantine Arabic

Gulf Arabic

Gulf Arabic, spoken by around 4 million people predominantly in the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Bahrain. Also spoken in Iran's Bushehr and Hormozgan provinces.

Other

Other varieties include:

Sounds

It is important to distinguish between the pronunciation of the "formal" Literary Arabic (usually specifically Modern Standard Arabic) and the "colloquial" spoken varieties of Arabic. The two types of Arabic, but significantly different. The "colloquial" varieties are learned at home and constitute the native languages of Arabic speakers. The literary variety is learned at school; although many speakers have a native-like command of the language, it is technically not the native language of any speakers. Both varieties can be both written and spoken, although the colloquial varieties are rarely written down, and the formal variety is spoken mostly in formal circumstances, e.g. in radio broadcasts, formal lectures, parliamentary discussions, and to some extent between speakers of different colloquial varieties. Even when the literary language is spoken, however, it is normal only spoken in its pure form when reading a prepared text out loud. When speaking extemporaneously (i.e. making up the language on the spot, as in a normal discussion among people), speakers tend to deviate somewhat from the strict literary language in the direction of the colloquial varieties. In fact, there is a continuous range of "in-between" spoken varieties: from nearly pure Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), to a form that still uses MSA grammar and vocabulary but with significant colloquial influence, to a form of the colloquial language that imports a number of words and grammatical constructions in MSA, to a form that is close to pure colloquial but with the "rough edges" (the most noticeably "vulgar" or non-Classical aspects) smoothed out, to pure colloquial. The particular variant (or register) used depends on the social class and education level of the speakers involved, and the level of formality of the speech situation. Often it will vary within a single encounter, e.g. moving from nearly pure MSA to a more mixed language in the process of a radio interview, as the interviewee becomes more comfortable with the interviewer. This type of variation is characteristic of the diglossia that exists throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

Literary Arabic

Although Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is a unitary language, its pronunciation varies somewhat from country to country and from region to region within a country. The variation in individual "accents" of MSA speakers tend to mirror corresponding variations in the colloquial speech of the speakers in question, but with the distinguishing characteristics moderated somewhat. Note that it is important in descriptions of "Arabic" phonology to distinguish between pronunciation of a given colloquial (spoken) dialect and the pronunciation of MSA by these same speakers. Although they are related, they are not the same. For example, the phoneme that derives from Proto-Semitic /g/ has many different pronunciations in the modern spoken varieties, e.g. . Speakers whose native variety has either or will use the same pronunciation when speaking MSA, even speakers from Cairo, whose native Egyptian Arabic has , normally use when speaking MSA. of Persian Gulf is the only pronunciation which isn't pronounced in MSA, but instead .Another example: Many colloquial varieties are known for a type of vowel harmony in which the presence of an "emphatic consonant" triggers backed allophones of nearby vowels (especially of the low vowels , which are backed to in these circumstances, and very often fronted to in all other circumstances). In many spoken varieties, the backed or "emphatic" vowel allophones spread a fair distance in both directions from the triggering consonant; in some varieties (most notably Egyptian Arabic), the "emphatic" allophones spread throughout the entire word, usually including prefixes and suffixes, even at a remove of several syllables from the triggering consonant. Speakers of colloquial varieties with this vowel harmony tend to introduce it into their MSA pronunciation as well, but usually with a lesser degree of spreading than in the colloquial varieties. (For example, speakers of colloquial varieties with extremely long-distance harmony may allow a moderate, but not extreme, amount of spreading of the harmonic allophones in their MSA speech, while speakers of colloquial varieties with moderate-distance harmony may only harmonize immediately adjacent vowels in MSA.)

Vowels

Modern Standard Arabic has six pure vowels, with short and corresponding long vowels . There are also two diphthongs: and .As mentioned above, the pronunciation of the vowels differs from speaker to speaker, in way that tend to echo the pronunciation of the corresponding colloquial variety. Nonetheless, there are some common trends. Most noticeable is the differing pronunciation of and , which tend towards fronted , or in most situations, but a back in the neighborhood of emphatic consonants. (Some accents and dialects, such as those of Hijaz, have central in all situations.) The vowels and are often affected somewhat in emphatic neighborhoods as well, with generally more back and/or centralized allophones, but the differences are less great than for the low vowels. The pronunciation of short and tends towards and in many dialects.

The definition of both "emphatic" and "neighborhood" vary in ways that echo (to some extent) corresponding variations in the spoken dialects. Generally, the consonants triggering "emphatic" allophones are the pharyngealized consonants ; ; and , if not followed immediately by . Frequently, the fricatives also trigger emphatic allophones; occasionally also the pharyngeal consonants (the former more than the latter). Many dialects have multiple emphatic allophones of each vowel, depending on the particular nearby consonants. In most MSA accents, emphatic coloring of vowels is limited to vowels immediately adjacent to a triggering consonant, although in some it spreads a bit farther: e.g. "time"; "homeland"; "downtown" (sometimes or similar).

In a non-emphatic environment, the vowel /a/ in the diphthong tends to be fronted even more than elsewhere, often pronounced or : hence "sword" but "summer"). However, in accents with no emphatic allophones of /a/ (e.g. in the Hijaz), the pronunciation occurs in all situations.

Consonants

| + Standardized Arabic consonant phonemes | ||||||||||||

| ! rowspan="2" | ! colspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ||||||

| ! plain | emphatic">Dental consonant | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | ! rowspan="2" | |||||

| ! plain | emphatic | emphatic consonant>emphatic | ! plain | |||||||||

| ! colspan=2 | ||||||||||||

| ! rowspan=2 | ! voiceless | |||||||||||

| voice (phonetics)>voiced | 3 | |||||||||||

| ! rowspan=2 | ! voiceless | 4 | ||||||||||

| voice (phonetics)>voiced | ||||||||||||

| ! colspan=2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| ! colspan=2 | ||||||||||||

NOTE: The underlined variants in the above table indicate the pronunciations considered "standard" according to descriptions in linguistic sources; the same pronunciations are normally taught to foreigners learning Literary Arabic. (The sources disagree about whether the sounds indicated above as ~ and ~ are more standardly or , or are unclear.)

See Arabic alphabet for explanations on the IPA phonetic symbols found in this chart.

# This phoneme is represented by the Arabic letter () and has many standard pronunciations. is characteristic of Iraq and most of the Arabian peninsula; occurs in the Levant and North Africa; and is used in Egypt and some regions in Yemen and Oman. Generally this corresponds with the pronunciation in the colloquial dialects. In some regions in Sudan and Yemen, as well as in some Sudanese and Yemeni dialects, it may be either or , representing the original pronunciation of Classical Arabic. Foreign words containing may be transcribed with , , , , , or , mainly depending on the regional spoken variety of Arabic. Note also that in northern Egypt, where the Arabic letter () is normally pronounced , a separate phoneme occurs in a small number of European loanwords, e.g. "jacket". # is pronounced in , the name of God, q.e. Allah, when the word follows a, ā, u or ū (after i or ī it is unvelarized: bismi l–lāh ). Some speakers velarize other occurrences of /l/ in MSA, in imitation of their spoken dialects. # The emphatic consonant was actually pronounced , or possibly — either way, a highly unusual sound. The medieval Arabs actually termed their language "the language of the Ḍād" (the name of the letter used for this sound), since they thought the sound was unique to their language. (In fact, it also exists in a few other minority Semitic languages, e.g. Mehri.) # In many varieties, () are actually epiglottal (despite what is reported in many earlier works). # and () are often post-velar, though velar and uvular pronunciations are also possible. # () can be pronounced as or even . In some places of Maghreb it can be also pronounced as .

Arabic has consonants traditionally termed "emphatic" (), which exhibit simultaneous pharyngealization as well as varying degrees of velarization , so they may be written with the "Velarized or pharyngealized" diacritic () as: . This simultaneous articulation is described as "Retracted Tongue Root" by phonologists. In some transcription systems, emphasis is shown by capitalizing the letter, for example, is written ‹D›; in others the letter is underlined or has a dot below it, for example, ‹›.

Vowels and consonants can be phonologically short or long. Long (geminate) consonants are normally written doubled in Latin transcription (i.e. bb, dd, etc.), reflecting the presence of the Arabic diacritic mark , which indicates doubled consonants. In actual pronunciation, doubled consonants are held twice as long as short consonants. This consonant lengthening is phonemically contrastive: "he accepted" vs. "he kissed."

Syllable structure

Arabic has two kinds of syllables: open syllables (CV) and (CVV)—and closed syllables (CVC), (CVVC), and (CVCC). The syllable types with three morae (units of time), i.e. CVC and CVV, are termed heavy syllables, while those with four morae, i.e. CVVC and CVCC, are superheavy syllables. Superheavy syllables in Classical Arabic occur in only two places: at the end of the sentence (due to pausal pronunciation), and in words such as "hot", "stuff, substance", "they disputed with each other", where a long occurs before two identical consonants (a former short vowel between the consonants has been lost). (In less formal pronunciations of Modern Standard Arabic, superheavy syllables are common at the end of words or before clitic suffixes such as "us, our", due to the deletion of final short vowels.)In surface pronunciation, every vowel must be preceded by a consonant (which may include the glottal stop ). There are no cases of hiatus within a word (where two vowels occur next to each other, without an intervening consonant). Some words do underlyingly begin with a vowel, such as the definite article al- or words such as "he bought", "meeting". When actually pronounced, one of three things happens: If the word occurs after another word ending in a consonant, there is a smooth transition from final consonant to initial vowel, e.g. "meeting" . If the word occurs after another word ending in a vowel, the initial vowel of the word is elided, e.g. "house of the director" . If the word occurs at the beginning of an utterance, a glottal stop is added onto the beginning, e.g. "The house is ..." .

Stress

Word stress is not phonemically contrastive in Standard Arabic. It bears a strong relationship to vowel length. The basic rules for Modern Standard Arabic are:Examples: "book", "writer", "desk", "desks", "library" (but "library" in short pronunciation), (Modern Standard Arabic) "they wrote" = (dialect), (Modern Standard Arabic) "they wrote it" = (dialect), (Modern Standard Arabic) "they (dual, fem) wrote", (Modern Standard Arabic) "I wrote" = (short form or dialect). Doubled consonants count as two consonants: "magazine", "place".

These rules may result in differently-stressed syllables when final case endings are pronounced, vs. the normal situation where they are not pronounced, as in the above example of "library" in full pronunciation, but "library" in short pronunciation.

The restriction on final long vowels does not apply to the spoken dialects, where original final long vowels have been shortened and secondary final long vowels have arisen from loss of original final -hu/hi.

Some dialects have different stress rules. In the Cairo (Egyptian Arabic) dialect a heavy syllable may not carry stress more than two syllables from the end of a word, hence "school", "Cairo". This also affects the way that Modern Standard Arabic is pronounced in Egypt. In the Arabic of Sana, stress is often retracted: "two houses", "their table", "desks", "sometimes", "their school". (In this dialect, only syllables with long vowels or diphthongs are considered heavy; in a two-syllable word, the final syllable can be stressed only if the preceding syllable is light; and in longer words, the final syllable cannot be stressed.)

Levels of pronunciation

The final short vowels (e.g. the case endings -a -i -u and mood endings -u -a) are often not pronounced, despite forming part of the formal paradigm of nouns and verbs. The following levels of pronunciation exist:

Full pronunciation

In full pronunciation, all endings are pronounced as written. This normally is used only in grammatical descriptions of the language.

Full pronunciation with pausa

This is the most formal level actually used in speech. All endings are pronounced as written, except at the end of an utterance, where the following changes occur:

Formal short pronunciation

This is a formal level of pronunciation sometimes seen. It is somewhat like pronouncing all words as if they were in pausal position (with influence from the colloquial varieties). The following changes occur:

Informal short pronunciation

This is the pronunciation used by speakers of Modern Standard Arabic in extemporaneous speech, i.e. when producing new sentences rather than simply reading a prepared text. It is similar to formal short pronunciation except that the rules for dropping final vowels apply even when a clitic suffix is added. Basically, short-vowel case and mood endings are never pronounced, and certain other changes occur that echo the corresponding colloquial pronunciations. Specifically:

Colloquial varieties

: The section below only refers to pronunciation

Vowels

As mentioned above, many spoken dialects have a process of emphasis spreading, where the "emphasis" (pharyngealization) of emphatic consonants spreads forward and back through adjacent syllables, pharyngealizing all nearby consonants and triggering the back allophone in all nearby low vowels. The extent of emphasis spreading varies. For example, in Moroccan Arabic, it spreads as far as the first full vowel (i.e. sound derived from a long vowel or diphthong) on either side; in many Levantine dialects, it spreads indefinitely, but is blocked by any or ; while in Egyptian Arabic, it usually spreads throughout the entire word, including prefixes and suffixes. In Moroccan Arabic, also have emphatic allophones .Unstressed short vowels, especially , are deleted in many contexts. Many sporadic examples of short vowel change have occurred (especially /a/→/i/, and interchange /i/↔/u/). Most Levantine dialects merge short /i u/ into /ǝ/ in most contexts (all except directly before a single final consonant). In Moroccan Arabic, on the other hand, short /u/ triggers labialization of nearby consonants (especially velar consonants and uvular consonants), and then short /a i u/ all merge into /ǝ/, which is deleted in many contexts. (The labialization plus /ǝ/ is sometimes interpreted as an underlying phoneme .) This essentially causes the wholesale loss of the short-long vowel distinction, with the original long vowels remaining as half-long , phonemically , which are used to represent both short and long vowels in borrowings from Literary Arabic.

Most spoken dialects have monophthongized original to (in all circumstances, including adjacent to emphatic consonants). In Moroccan Arabic, these have subsequently merged into original .

Consonants

In some dialects, there may be more or fewer phonemes than those listed in the chart above. For example, non-Arabic is used in the Maghrebi dialects as well in the written language mostly for foreign names. Semitic became extremely early on in Arabic before it was written down; a few modern Arabic dialects, such as Iraqi (influenced by Persian and Turkish) distinguish between and . The Iraqi Arabic uses also sounds , and uses Persian adding letters, e.g.: – a plum; – a truffle'' and so on.Early in the expansion of Arabic, the separate emphatic phonemes and coalesced into a single phoneme . Many dialects (such as Egyptian, Levantine, and much of the Maghreb) subsequently lost fricatives, converting into . Most dialects borrow "learned" words from the Standard language using the same pronunciation as for inherited words, but some dialects without interdental fricatives (particularly in Egypt and the Levant) render original in borrowed words as .

Another key distinguishing mark of Arabic dialects is how they render the original velar and uvular stops , (Proto-Semitic ), and : retains its original pronunciation in widely scattered regions such as Yemen, Morocco, and urban areas of the Maghreb. It is pronounced as a glottal stop in several prestige dialects, such as those spoken in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus. But it is rendered as a voiced velar stop in Gulf Arabic, Iraqi Arabic, Upper Egypt, much of the Maghreb, and less urban parts of the Levant (e.g. Jordan). Some traditionally Christian villages in rural areas of the Levant render the sound as , as do Shia Bahrainis. In some Gulf dialects, it is palatalized to or . It is pronounced as a voiced uvular constrictive in Sudanese Arabic. Many dialects with a modified pronunciation for maintain the pronunciation in certain words (often with religious or educational overtones) borrowed from the Classical language. is pronounced as an affricate in Iraq and much of the Arabian Peninsula, but is pronounced in most of North Egypt and parts of Yemen and Oman, in Morocco, Tunisia and the Levant, and , in most words in much of Gulf Arabic. usually retains its original pronunciation, but is palatalized to in many words in Israel & the Palestinian Territories, Iraq and much of the Arabian Peninsula. Often a distinction is made between the suffixes (you, masc.) and (you, fem.), which become and , respectively. In Sana'a, Omani, and Bahrani is pronounced .

Pharyngealization of the emphatic consonants tends to weaken in many of the spoken varieties, and to spread from emphatic consonants to nearby sounds. In addition, the "emphatic" allophone automatically triggers pharyngealization of adjacent sounds in many dialects. As a result, it may difficult or impossible to determine whether a given coronal consonant is phonemically emphatic or not, especially in dialects with long-distance emphasis spreading. (A notable exception is the sounds vs. in Moroccan Arabic, because the former is pronounced as an affricate but the latter is not.)

Grammar

Literary Arabic