- go to the top

- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

Ali Bardakoğlu

Ali Bardakoğlu (born 1952) is the current president of Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı (Presidency of Religious Affairs) and as such the highest Islamic authority in Turkey.

http://wn.com/Ali_Bardakoğlu -

Arjuna

Arjuna or Arjun (Devanagari: अर्जुन, Thai: Archun, Tamil: Archunan; pronounced in classical Sanskrit) is one of the Pandavas, the heroes of the Hindu epic Mahābhārata. Arjuna, whose name means 'bright', 'shining', 'white' or 'silver' (cf. Latin argentum), was such a peerless archer that he is often referred to as Jishnu - the undefeatable. The third of the five Pandava brothers, Arjuna was one of the children borne by Kunti, the first wife of Pandu. Arjuna is considered to have an "Amsha" of Nara. Nara is one of the forms of Lord Narayana. He is sometimes referred to as the 'fourth Krishna' of the Mahabharata. One of his most important roles was as the dear friend and brother-in-law of Lord Krishna, from whom he heard the Bhagavad Gita before the battle of Kurukshetra.

http://wn.com/Arjuna -

Buddhism

Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद्ध धर्म Buddha Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth.

http://wn.com/Buddhism -

Dean Ornish

Dean Michael Ornish, M.D., (born July 16, 1953) is president and founder of the nonprofit Preventive Medicine Research Institute in Sausalito, California, as well as Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

http://wn.com/Dean_Ornish -

Dharma Mittra

Sri Dharma Mittra is a Yoga teacher, and a student of Sri Swami Kailashananda Maharaj. Best known for creating the Master Yoga Chart of 908 Postures, his "influence on the yoga world extends far beyond the nearly 50,000 copies of that poster that have been printed since Mittra completed the laborious project in 1983." He has been teaching since 1967, and is director of the Dharma Yoga Center in New York City.

http://wn.com/Dharma_Mittra -

Ernest Wood

Professor Ernest Egerton Wood (* 18 August 1883 in Manchester, England; + 17 September 1965 in Houston, United States) was a noted yogi, theosophist, Sanskrit scholar, and author of numerous books, including Concentration - An Approach to Meditation and Yoga.

http://wn.com/Ernest_Wood -

Gregory Possehl

Gregory Possehl is a Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of the Asian Collections at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. He has been involved in excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization in India and Pakistan since 1964, and is an author of many books and articles on the Indus Civilization and related topics. He received his BA in Anthropology from the University of Washington in 1964, his MA in Anthropology from the University of Washington in 1967, and his PhD in Anthropology from the University of Chicago in 1974. He has conducted major excavations in Gujarat (Rojdi, Babar Kot and Oriyo Timbo), Rajasthan (Gilund), and in January 2007, began an excavation at the UNESCO World Heritage site of Bat in the Sultanate of Oman.

http://wn.com/Gregory_Possehl -

Hajime Nakamura

was a Japanese academic of Vedic, Hindu and Buddhist scriptures. Nakamura was an expert on Sanskrit and Pali, and among his many writings are commentaries on Buddhist scriptures. He is most known in Japan as the first to translate the entire Pali Tripitaka into Japanese. This work is still considered as the definitive translation to date against which later translations are measured. The footnotes in his Pali translation often refer to other previous translations in German, English, French as well as the ancient Chinese translations of Sanskrit scriptures.

http://wn.com/Hajime_Nakamura -

Haribhadra

Haribhadra Suri (c.700-c.770, or 459-529, traditional) was a Svetambara mendicant Jain leader and author.

http://wn.com/Haribhadra -

Heinrich Dumoulin

Heinrich Dumoulin, S.J. (May 31, 1905—July 21, 1995) was a Jesuit theologian, a widely published author on Zen Buddhism, and a professor of philosophy and history at Sophia University in Tokyo, Japan (where he was Professor Emeritus). He was the founder of its Institute for Oriental Religions, as well as the first Director of the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

http://wn.com/Heinrich_Dumoulin -

Heinrich Zimmer

Heinrich Robert Zimmer (1890–1943) was an Indologist and historian of South Asian art, most known for his works, Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization and Philosophies of India.

http://wn.com/Heinrich_Zimmer -

I. K. Taimni

I. K. Taimni (1898-1978) was a Professor of Chemistry at the Allahabad University in India, and an influential scholar in the fields of Yoga and Indian Philosophy. He was a leader of the Theosophical Society and taught and practiced yoga most of his life. Taimni authored a number of books on Eastern Philosophy, including a modern interpretation of Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.

http://wn.com/I_K_Taimni -

K. Pattabhi Jois

Sri Krishna Pattabhi Jois ()(July 26, 1915 – May 18, 2009) was an Indian yoga teacher. He was a student of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, and taught at his school, the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute, in Mysore, India.

http://wn.com/K_Pattabhi_Jois -

Kundakunda

Kundakunda (also Kundkund) is a celebrated Jain Acharya, Jain scholar monk, 2nd century CE, composer of spiritual classics such as: Samayasara, Niyamasara, Pancastikayasara, Pravacanasara, Atthapahuda and Barasanuvekkha. He occupies the highest place in the tradition of the Jain acharyas.

http://wn.com/Kundakunda -

Lahiri Mahasaya

Shyama Charan Lahiri (Bengali: শ্যাম চরণ লাহিড়ী Shêm Chôron Lahiṛi), best known as Lahiri Mahasaya (September 30, 1828 – September 26, 1895) was an Indian yogi and a disciple of Mahavatar Babaji. He revived the yogic science of Kriya Yoga when he learned it from Mahavatar Babaji in 1861. Lahiri Mahasaya was also the guru of Sri Yukteswar Giri. Mahasaya is a Sanskrit word meaning 'great soul'.

http://wn.com/Lahiri_Mahasaya -

Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit महावीर, Kannada ಮಹಾವೀರ and Tamil அருகன்("Arugan") lit. "Great Hero", traditionally 599 – 527 BCE) is the name most commonly used to refer to the Indian sage Vardhamana (Sanskrit: वर्धमान "increasing") who established what are today considered to be the central tenets of Jainism. According to Jain tradition, he was the 24th and the last Tirthankara. In Tamil, he is referred to as Arugan or Arugadevan. He is also known in texts as Vira or Viraprabhu, Sanmati, Ativira,and Gnatputra. In the Buddhist Pali Canon, he is referred to as Nigantha Nātaputta.

http://wn.com/Mahavira -

Max Müller

Friedrich Max Müller (December 6, 1823 – October 28, 1900), more regularly known as Max Müller, was a German philologist and Orientalist, one of the founders of the western academic field of Indian studies and the discipline of comparative religion. Müller wrote both scholarly and popular works on the subject of Indology, a discipline he introduced to the British reading public, and the Sacred Books of the East, a massive, 50-volume set of English translations prepared under his direction, stands as an enduring monument to Victorian scholarship.

http://wn.com/Max_Müller -

Patanjali

http://wn.com/Patanjali -

Robert J. Zydenbos

Robert J. Zydenbos is a Dutch-Canadian scholar who has doctorate degrees in Indian philosophy and Dravidian studies. He also has a doctorate of literature from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Zydenbos also studied Indian religions and languages at the South Asia Institute and at the University of Heidelberg in Germany. He taught Sanskrit at the University of Heidelberg and later taught Jaina philosophy at the University of Madras in India. Zydenbos later taught Sanskrit, Buddhism, and South Asian religions at the University of Toronto in Canada. He was the first western scholar to write a doctoral thesis on contemporary Kannada fiction.

http://wn.com/Robert_J_Zydenbos -

Swami Prabhavananda

Swami Prabhavananda (December 26, 1893 – July 4, 1976) was an Indian philosopher, monk of the Ramakrishna Order, and religious teacher.

http://wn.com/Swami_Prabhavananda -

Swami Satchidananda

Swami Satchidananda (December 22, 1914 – August 19, 2002), born as C. K. Ramaswamy Gounder, was an Indian religious teacher, spiritual master and yoga adept, who gained fame and following in the West, during his time in New York. He was the author of many philosophical and spiritual books, including a popular illustrative book on Hatha Yoga. He is widely known in India, particularly Southern India, as the spiritual guru of the Indian cinema star Rajinikanth.He also founded the school Satchidananda Jothi Niketan located in Mettupalyam, Tamil Nadu.

http://wn.com/Swami_Satchidananda -

Swami Sivananda

Swami Sivananda Saraswati (September 8, 1887—July 14, 1963) was a Hindu spiritual teacher and a well known proponent of Yoga and Vedanta. Sivananda was born Kuppuswami in Pattamadai, in the Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu. He studied medicine and served in Malaya as a physician for several years before taking up monasticism. He lived most of the later part of his life near Muni Ki Reti, Rishikesh.

http://wn.com/Swami_Sivananda -

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (, Shami Bibekānondo) (January 12, 1863–July 4, 1902), born Narendranath Dutta () was the chief disciple of the 19th century mystic Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and the founder of Ramakrishna Mission. He is considered a key figure in the introduction of Hindu philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America and is also credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the end of the 19th century. Vivekananda is considered to be a major force in the revival of Hinduism in modern India. He is perhaps best known for his inspiring speech beginning with "Sisters and Brothers of America", through which he introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions at Chicago in 1893.

http://wn.com/Swami_Vivekananda -

Thomas McEvilley

Thomas McEvilley (born 1939, Cincinnati, Ohio) is an American art critic, poet, novelist and scholar, who was a distinguisted lecturer in art history at Rice University and founder and former head of the Department of Art Criticism and Writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

http://wn.com/Thomas_McEvilley -

Yogi Swatmarama

Yogi Swatmarama was a 15th and 16th century yogic sage in India. He is best known for compiling the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, which introduced the system of Hatha Yoga. Hatha Yoga focuses on purification of the body as a path that leads to purification of the mind (ha), and prana, or vital energy (tha).

http://wn.com/Yogi_Swatmarama -

Yukteswar Giri

http://wn.com/Yukteswar_Giri

-

Bangalore

Bangalore , known as Bengaluru (), is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. Bangalore is nicknamed the Garden City and was once called a pensioner's paradise. Located on the Deccan Plateau in the south-eastern part of Karnataka, Bangalore is India's third most populous city and fifth-most populous urban agglomeration. As of 2009, Bangalore was inducted in the list of Global cities and ranked as a "Beta World City" alongside Geneva, Copenhagen, Boston, Cairo, Riyadh, Berlin, to name a few, in the studies performed by the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network in 2008.

http://wn.com/Bangalore -

Darul Uloom Deoband

The Darul Uloom Deoband (, ) is an Islamic school propagating Sunni Islam in India and is where the Deobandi Islamic movement was started. It is located at Deoband, a town in Uttar Pradesh, India. It was founded in 1866 by several prominent Islamic scholars (ulema), headed by Maulana Muhammad Qasim Nanautawi. The other prominent founding scholars were Maulana Rashid Ahmad Gangohi and Haji Syed Abid Hussain. The institution is highly respected across the India, as well as in other parts of the Indian subcontinent.

http://wn.com/Darul_Uloom_Deoband -

Delhi

Delhi, known locally as Dilli (, , {{Lang-ur| '), and by the official name National Capital Territory of Delhi''' (NCT), is the largest metropolis by area and the second-largest metropolis by population in India. It is the eighth largest metropolis in the world by population with more than 12.25 million inhabitants in the territory and with nearly 22.2 million residents in the National Capital Region urban area (which also includes Noida, Gurgaon, Greater Noida, Faridabad and Ghaziabad). The name Delhi is often also used to include some urban areas near the NCT, as well as to refer to New Delhi, the capital of India, which lies within the metropolis. The NCT is a federally administered union territory.

http://wn.com/Delhi -

Holy Office

http://wn.com/Holy_Office -

India

India (), officially the Republic of India ( ; see also official names of India), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.18 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world. Mainland India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the west, and the Bay of Bengal on the east; and it is bordered by Pakistan to the west; Bhutan, the People's Republic of China and Nepal to the north; and Bangladesh and Burma to the east. In the Indian Ocean, mainland India and the Lakshadweep Islands are in the vicinity of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, while India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands share maritime border with Thailand and the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the Andaman Sea. India has a coastline of .

http://wn.com/India -

Japan

Japan (日本 Nihon or Nippon), officially the State of Japan ( or Nihon-koku), is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south. The characters that make up Japan's name mean "sun-origin" (because it lies to the east of nearby countries), which is why Japan is sometimes referred to as the "Land of the Rising Sun".

http://wn.com/Japan

- Advaita Vedanta

- Ali Bardakoğlu

- Alvars

- ancient India

- Anuttara yoga

- Anuyoga

- Arjuna

- Asana

- asanas

- ascetic

- astika

- Atiyoga

- Atman (Hinduism)

- B.K.S. Iyengar

- bandha

- Bangalore

- Bhagavad Gita

- Bhagavadgita

- Bhagavata Purana

- bhakti

- Bhakti movement

- Bhakti Yoga

- bhaktiyoga

- Birla Mandir

- Blasphemy in Islam

- bodhisattva

- Brahma

- Brahman

- Brahmana

- Buddhism

- Chakra

- Classical Hinduism

- CNN

- Council of Ulemas

- counter culture

- Darul Uloom Deoband

- Dean Ornish

- Delhi

- Deobandi

- Dhammapada

- Dharana

- Dharma Mittra

- dhyana

- Dhyana in Hinduism

- Dhyāna in Buddhism

- early Buddhism

- Epic Sanskrit

- Ernest Wood

- esotericism

- fatwa

- Gaudiya Vaishnavism

- god

- Gregory Possehl

- Gupta era

- Gupta period

- Hajime Nakamura

- haraam

- Haribhadra

- Hatha Yoga

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika

- Heinrich Dumoulin

- Heinrich Zimmer

- Hemacandra

- Hindu

- Hindu philosophy

- Hindu revivalism

- Hindu texts

- Hinduism

- Holy Office

- Human body

- I. K. Taimni

- India

- Indian religions

- Indologist

- Ishvara

- Islam

- Jainism

- Japan

- jhana

- Jhana in Theravada

- Jhāna

- Jnana Yoga

- Jogi (castes)

- Jogi Faqir

- jñānayoga

- K. Pattabhi Jois

- Karma in Jainism

- Karma Yoga

- karmayoga

- Katha Upanishad

- Kayotsarga

- Krishna

- Krishnaism

- Kriya Yoga

- kriyāyoga

- Kundakunda

- Kundalini Yoga

- Lahiri Mahasaya

- Lotus position

- Lukhang

- Mahabharata

- Mahavatar Babaji

- Mahavira

- Mahavrata

- Mahayana Buddhism

- Mahayoga

- Mauryan Empire

- Max Müller

- Maya (illusion)

- mind

- Moksha

- Monism

- Motilal Banarsidass

- Muslim

- Nasadiya Sukta

- Neo-Hindu

- New Age

- New Age movement

- Niyama

- Nyingma

- Parsva

- Patanjali

- personal God

- prana

- Pranayama

- Pratyahara

- Pāli

- Raja yoga

- Ratnatraya

- Richard Gombrich

- Robert J. Zydenbos

- Robert Svoboda

- Rsabha

- Rāja Yoga

- Samkhya

- Samsara

- Samādhi

- Sannyasa

- Sanskrit

- Shaivism

- shatkarma

- shramana

- Sisters in Islam

- soul

- spiritual practice

- Sri Krishnamacharya

- Sri Yogendra

- Sufi

- Supreme Being

- Svayam bhagavan

- Swami Kuvalyananda

- Swami Prabhavananda

- Swami Satchidananda

- Swami Sivananda

- Swami Vivekananda

- tantra

- Tantrism

- Tapas (Sanskrit)

- Tattvarthasutra

- Thomas McEvilley

- Three Yogas

- Tibetan Buddhism

- Trul khor

- tummo

- Umasvati

- Upanishads

- Vaishnavism

- Vedanta

- Vedas

- Vedic chant

- Vedic Sanskrit

- Vishnu

- World Wisdom

- Yamas

- Yoga as exercise

- Yoga Journal

- Yogacara

- yogi

- Yogi Swatmarama

- yogini

- Yukteswar Giri

- Zen

- āstika

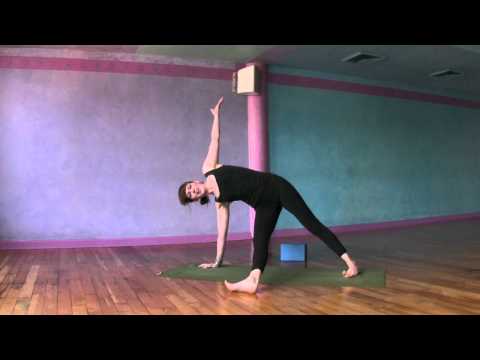

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:00

- Published: 27 Mar 2007

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: myyogaonline

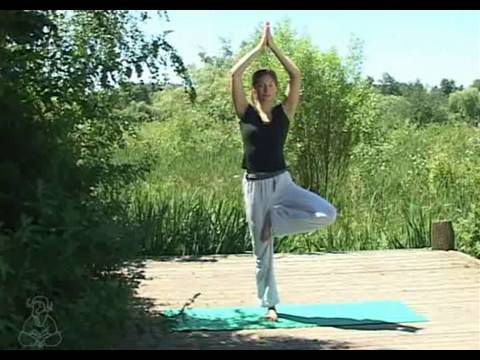

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:46

- Published: 11 Nov 2006

- Uploaded: 19 Nov 2011

- Author: prajnayoga

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 9:50

- Published: 05 May 2010

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: TaraStilesYoga

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 17:50

- Published: 12 Jul 2011

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: sadienardini

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 10:02

- Published: 15 Sep 2008

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: sadienardini

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 7:12

- Published: 19 Feb 2010

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: TaraStilesYoga

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:56

- Published: 29 Jun 2008

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: sadienardini

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:29

- Published: 20 Jun 2007

- Uploaded: 17 Nov 2011

- Author: GoPotatoTV

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:02

- Published: 29 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: ShortyTheCat2010

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 17:12

- Published: 02 Nov 2011

- Uploaded: 18 Nov 2011

- Author: YogaJournal

size: 0.7Kb

size: 1.5Kb

- Advaita Ashrama

- Advaita Vedanta

- Ali Bardakoğlu

- Alvars

- ancient India

- Anuttara yoga

- Anuyoga

- Arjuna

- Asana

- asanas

- ascetic

- astika

- Atiyoga

- Atman (Hinduism)

- B.K.S. Iyengar

- bandha

- Bangalore

- Bhagavad Gita

- Bhagavadgita

- Bhagavata Purana

- bhakti

- Bhakti movement

- Bhakti Yoga

- bhaktiyoga

- Birla Mandir

- Blasphemy in Islam

- bodhisattva

- Brahma

- Brahman

- Brahmana

- Buddhism

- Chakra

- Classical Hinduism

- CNN

- Council of Ulemas

- counter culture

- Darul Uloom Deoband

- Dean Ornish

- Delhi

- Deobandi

- Dhammapada

- Dharana

- Dharma Mittra

- dhyana

- Dhyana in Hinduism

- Dhyāna in Buddhism

- early Buddhism

- Epic Sanskrit

- Ernest Wood

- esotericism

- fatwa

- Gaudiya Vaishnavism

- god

- Gregory Possehl

- Gupta era

- Gupta period

- Hajime Nakamura

- haraam

- Haribhadra

- Hatha Yoga

size: 5.3Kb

size: 4.3Kb

size: 0.8Kb

size: 5.4Kb

size: 2.0Kb

size: 5.9Kb

size: 4.9Kb

size: 4.9Kb

size: 4.9Kb

Yoga (Sanskrit, Pāli: ) is a physical, mental, and spiritual discipline, originating in ancient India, whose goal is the attainment of a state of perfect spiritual insight and tranquility. The word is associated with meditative practices in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism..

Within Hindu philosophy, the word yoga is used to refer to one of the six orthodox (āstika) schools of Hindu philosophy. Yoga in this sense is based on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and is also known as Rāja Yoga to distinguish it from later schools. Patanjali's system is discussed and elaborated upon in many classical Hindu texts, and has also been influential in Buddhism and Jainism. The Bhagavadgita introduces distinctions such as Jnana Yoga ("yoga based on knowledge") vs. Karma Yoga ("yoga based on action").

Other systems of philosophy introduced in Hinduism during the medieval period are Bhakti Yoga, and Hatha Yoga.

The Sanskrit word has the literal meaning of "yoke", from a root meaning to join, to unite, or to attach. As a term for a system of abstract meditation or mental abstraction it was introduced by Patanjali in the 2nd century BC. Someone who practices yoga or follows the yoga philosophy with a high level of commitment is called a yogi or yogini.

The goals of yoga are varied and range from improving health to achieving Moksha. For the bhakti schools of Vaishnavism, bhakti or service to Svayam bhagavan itself may be the ultimate goal of the yoga process, where the goal is to enjoy an eternal relationship with Vishnu.

Terminology

The Sanskrit word has the literal meaning of "yoke", or "the act of yoking or harnessing", from a root . In Vedic Sanskrit, the term "yoga" besides its literal meaning, the yoking or harnessing of oxen or horses, already has a figurative sense, where it takes the general meaning of "employment, use, application, performance" (compare the figurative uses of "to harness" as in "to put something to some use"). All further developments of the sense of this word are post-Vedic. A sense of "exertion, endeavour, zeal, diligence" is found in Epic Sanskrit. The more technical sense of the term "yoga", describing a system of meditation or contemplation with the aim of the cessation of mental activity and the attaining of a "supreme state" arises with early Buddhism (5th century BC), and is adopted in Vedanta philosophy by the 4th century BC.There are a great many compounds containing yoga in Sanskrit, many of them unrelated to the technical or spiritual sense the word has taken in Vedanta. Yoga in these words takes meanings such as "union, connection, contact", or "method, application, performance", etc. For example, guṇá-yoga means "contact with a cord"; cakrá-yoga has a medical sense of "applying a splint or similar instrument by means of pulleys (in case of dislocation of the thigh)"; candrá-yoga has the astronomical sense of "conjunction of the moon with a constellation"; puṃ-yoga is a grammatical term expressing "connection or relation with a man", etc.

Many such compounds are also found in the wider field of religion. Thus, bhakti-yoga means "devoted attachment" in the monotheistic Bhakti movement. The term kriyā-yoga has a grammatical sense, meaning "connection with a verb". But the same compound is also given a technical meaning in the Yoga Sutras (2.1), designating the "practical" aspects of the philosophy, i.e. the "union with the Supreme" due to performance of duties in everyday life.

History

Before Patanjali

Prehistory

Several seals discovered at Indus Valley Civilization sites, dating to the mid 3rd millennium BC, depict figures in positions resembling a common yoga or meditation pose, showing "a form of ritual discipline, suggesting a precursor of yoga," according to archaeologist Gregory Possehl. Some type of connection between the Indus Valley seals and later yoga and meditation practices is speculated upon by many scholars, though there is no conclusive evidence. More specifically, scholars and archaeologists have remarked on close similarities in the yogic and meditative postures depicted in the seals with those of various Tirthankaras: the "kayotsarga" posture of Rsabha and the "mulabandhasana" of Mahavira along with seals depicting meditative figure flanked by upright serpents bearing similarities to iconography of Parsva. All these are indicative of not only links between Indus Valley Civilisation and Jainism, but also show the contribution of Jainism to various yogic practices.Techniques for experiencing higher states of consciousness in meditation were developed by the shramanic traditions and in the Upanishadic tradition.

While there is no clear evidence for meditation in pre-Buddhist early Brahminic texts, there is a view that formless meditation might have originated in the Brahminic tradition. This is based on strong parallels between Upanishadic cosmological statements and the meditative goals of the two teachers of the Buddha as recorded in early Buddhist texts. As well as some less likely possibilities, the view put forward is that cosmological statements in the Upanishads reflect a contemplative tradition, and it is concluded that the Nasadiya Sukta contains evidence for a contemplative tradition, even as early as the late Rg Vedic period.

Early Buddhism

The more technical sense of the term "yoga", describing a system of meditation or contemplation with the aim of the cessation of mental activity and the attaining of a "supreme state" arises with early Buddhism. The Buddhist texts are probably the earliest texts describing meditation techniques altogether. They describe meditative practices and states that existed before the Buddha, as well as those first developed within Buddhism.In Hindu scripture, this sense of the term "yoga" first appears in the middle Upanishads, such as the Katha Upanishad (ca. 400 BCE). Shvetashvatara Upanishad mentions, "When earth, water fire, air and akasa arise, when the five attributes of the elements, mentioned in the books on yoga, become manifest then the yogi's body becomes purified by the fire of yoga and he is free from illness, old age and death." (Verse 2.12). More importantly in the following verse (2.13) it mentions, the "precursors of perfection in yoga", namely lightness and healthiness of the body, absence of desire, clear complexion, pleasantness of voice, sweet odour and slight excretions.

Early Buddhism incorporated meditative absorption states. The most ancient sustained expression of yogic ideas is found in the early sermons of the Buddha. One key innovative teaching of the Buddha was that meditative absorption must be combined with liberating cognition. The difference between the Buddha's teaching and the yoga presented in early Brahminic texts is striking. Meditative states alone are not an end, for according to the Buddha, even the highest meditative state is not liberating. Instead of attaining a complete cessation of thought, some sort of mental activity must take place: a liberating cognition, based on the practice of mindful awareness.

The Buddha also departed from earlier yogic thought in discarding the early Brahminic notion of liberation at death. Liberation for the Brahminic yogin was thought to be the realization at death of a nondual meditative state anticipated in life. In fact, old Brahminic metaphors for the liberation at death of the yogic adept ("becoming cool," "going out") were given a new meaning by the Buddha; their point of reference became the sage who is liberated in life.

Indian Antiquity

Classical Yoga as a system of contemplation with the aim of uniting the human spirit with Ishvara, the "Supreme Being" developed in early Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism during Indian Antiquity, between the Mauryan and the Gupta era (roughly the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE).

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

In Hindu philosophy, Yoga is the name of one of the six orthodox philosophical schools. The Yoga philosophical system is closely allied with the Samkhya school. The Yoga school as expounded by the sage Patanjali accepts the Samkhya psychology and metaphysics, but is more theistic than the Samkhya, as evidenced by the addition of a divine entity to the Samkhya's twenty-five elements of reality. The parallels between Yoga and Samkhya were so close that Max Müller says that "the two philosophies were in popular parlance distinguished from each other as Samkhya with and Samkhya without a Lord...." The intimate relationship between Samkhya and Yoga is explained by Heinrich Zimmer:

These two are regarded in India as twins, the two aspects of a single discipline. provides a basic theoretical exposition of human nature, enumerating and defining its elements, analyzing their manner of co-operation in a state of bondage ("bandha"), and describing their state of disentanglement or separation in release (""), while Yoga treats specifically of the dynamics of the process for the disentanglement, and outlines practical techniques for the gaining of release, or "isolation-integration" ("kaivalya").

Patanjali is widely regarded as the founder of the formal Yoga philosophy. Patanjali's yoga is known as Raja yoga, which is a system for control of the mind. Patanjali defines the word "yoga" in his second sutra, which is the definitional sutra for his entire work:

- Yoga Sutras 1.2

This terse definition hinges on the meaning of three Sanskrit terms. I. K. Taimni translates it as "Yoga is the inhibition () of the modifications () of the mind ()". The use of the word in the opening definition of yoga is an example of the important role that Buddhist technical terminology and concepts play in the Yoga Sutra; this role suggests that Patanjali was aware of Buddhist ideas and wove them into his system. Swami Vivekananda translates the sutra as "Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis)."

Patanjali's writing also became the basis for a system referred to as "Ashtanga Yoga" ("Eight-Limbed Yoga"). This eight-limbed concept derived from the 29th Sutra of the 2nd book, and is a core characteristic of practically every Raja yoga variation taught today. The Eight Limbs are: #Yama (The five "abstentions"): non-violence, non-lying, non-covetousness, non-sensuality, and non-possessiveness. #Niyama (The five "observances"): purity, contentment, austerity, study, and surrender to god. #Asana: Literally means "seat", and in Patanjali's Sutras refers to the seated position used for meditation. #Pranayama ("Suspending Breath"): Prāna, breath, "āyāma", to restrain or stop. Also interpreted as control of the life force. #Pratyahara ("Abstraction"): Withdrawal of the sense organs from external objects. #Dharana ("Concentration"): Fixing the attention on a single object. #Dhyana ("Meditation"): Intense contemplation of the nature of the object of meditation. #Samādhi ("Liberation"): merging consciousness with the object of meditation.

In the view of this school, the highest attainment does not reveal the experienced diversity of the world to be illusion. The everyday world is real. Furthermore, the highest attainment is the event of one of many individual selves discovering itself; there is no single universal self shared by all persons.

Yoga and Samkhya

Patanjali systematized the conceptions of Yoga and set them forth on the background of the metaphysics of Samkhya, which he assumed with slight variations. In the early works, the Yoga principles appear along with the Samkhya ideas. Vyasa's commentary on the Yoga Sutras, also called the “Samkhyapravacanabhasya,” brings out the intimate relation between the two systems.Yoga agrees with the essential metaphysics of Samkhya, but differs from it in that while Samkhya holds that knowledge is the means of liberation, Yoga is a system of active striving, mental discipline, and dutiful action. Yoga also introduces the conception of God. Sometimes Patanjali's system is referred to as “Seshvara Samkhya” in contradistinction to Kapila's "Nirivara Samkhya."

Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita ('Song of the Lord'), uses the term "yoga" extensively in a variety of ways. In addition to an entire chapter (ch. 6) dedicated to traditional yoga practice, including meditation, it introduces three prominent types of yoga:In Chapter 2 of the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna explains to Arjuna about the essence of Yoga as practiced in daily lives:

- Bhagavad Gita 2.48

A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada translates it as "Be steadfast in yoga (), O Arjuna. Perform your duty () and abandon all attachment () to success or failure (). Such evenness of mind () is called yoga."

Madhusudana Sarasvati (b. circa 1490) divided the Gita into three sections, with the first six chapters dealing with Karma yoga, the middle six with Bhakti yoga, and the last six with Jnana (knowledge). Other commentators ascribe a different 'yoga' to each chapter, delineating eighteen different yogas.

Yoga and Jainism

According to "Tattvarthasutra," 2nd century CE Jain text, "Yoga," is the sum total of all the activities of mind, speech and body. Umasvati calls yoga the cause of "asrava" or karmic influx as well as one of the essentials—samyak caritra—in the path to liberation. In his "Niyamasara," Acarya Kundakunda, describes yoga bhakti—devotion to the path to liberation—as the highest form of devotion. Acarya Haribhadra and Acarya Hemacandra mention the five major vows of ascetics and 12 minor vows of laity under yoga. This has led certain Indologists like Prof. Robert J. Zydenbos to call Jainism, essentially, a system of yogic thinking that grew into a full-fledged religion.The five yamas or the constraints of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali bear a resemblance to the five major vows of Jainism, indicating a history of strong cross-fertizization between these traditions.

Yogacara school

In the late phase of Indian antiquity, on the eve of the development of Classical Hinduism, the Yogacara movement arises during the Gupta period (4th to 5th centuries). Yogacara received the name as it provided a "yoga," a framework for engaging in the practices that lead to the path of the bodhisattva. The Yogacara sect teaches "yoga" as a way to reach enlightenment.

Middle Ages

The practice of Yoga remained in development in Classical Hinduism, and cognate techniques of meditation within Buddhism, throughout the medieval period.

Yoga in classical Jain literature

Earliest of Jain canonical literature like Acarangasutra and texts like Niyamasara, Tattvarthasutra etc. had many references on yoga as a way of life for laymen and ascetics. The later texts that further elaborated on the Jain concept of yoga are as follows:

Bhakti movement

The Bhakti movement was a development in medieval Hinduism advocating the concept of a personal God (or "Supreme Personality of Godhead"), initated by the Alvars of South India in the 6th to 9th centuries, and gaining influence throughout India by the 12th to 15th centuries, giving rise to sects such as Gaudiya Vaishnavism. The Bhagavata Purana is an important text of the Bhakti movement within Vaishnavism. It focusses on the concept of bhakti (devotion to God) in the theological framework of Krishnaism.The Bhagavata Purana discusses religious devotion as a kind of yoga, called bhaktiyoga. It also emphasizes kriyāyoga, i.e. the devotion to the deity in everday life (4.13.3).

The Bhagavata Purana is a commentary and elaboration on the Bhagavadgita, an older text of the Mahabharata epic which rose to great importance in Vaishnavism during the Bhakti movement. In the Bhagavadgita (3.3), jñānayoga is the acquisition of true knowledge, as opposed to karmayoga, the performance of the proper religious rites.

This terminology involving various yogas has given rise to the concept of the Four Yogas in modern Hinduism from the 1890s. These are #Karma Yoga #Bhakti Yoga #Raja Yoga #Jnana Yoga In this usage, the term "Yoga" ceases to translate to "a system of meditation" and takes on the much more general sense of "religious path". Thus, Karma Yoga is "the Path of Action", Bhakti Yoga "the Path of Devotion" and Jnana Yoga "the Path of Knowledge", all standing alongside Raja Yoga, "the Path of Meditation" as alternative possibilities towards religious fulfillment.

Hatha Yoga

Hatha Yoga is a particular system of Yoga described by Yogi Swatmarama, compiler of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika in 15th century India. Hatha Yoga differs substantially from the Raja Yoga of Patanjali in that it focuses on "shatkarma," the purification of the physical body as leading to the purification of the mind ("ha"), and "prana," or vital energy (tha). Compared to the seated asana, or sitting meditation posture, of Patanjali's Raja yoga, it marks the development of asanas (plural) into the full body 'postures' now in popular usage and, along with its many modern variations, is the style that many people associate with the word "Yoga" today.

Modern history

Hindu revivalism

New schools of Yoga were introduced in the context of Hindu revivalism towards the end of the 19th century.The physical poses of Hatha Yoga have a tradition that goes back to the 15th century, but they were not widely practiced in India prior to the early 20th century. Hatha Yoga was advocated by a number of late 19th to early 20th century gurus in India, including Sri Krishnamacharya in south India, Swami Sivananda in the north, Sri Yogendra in Bombay, and Swami Kuvalyananda in Lonavala.

In 1946, Paramahansa Yogananda in his Autobiography of a Yogi introduced the term Kriya Yoga for the tradition of Yoga transmitted by his lineage of gurus, deriving it via Yukteswar Giri and Lahiri Mahasaya from Mahavatar Babaji (fl. 1860s). Also influential in the development of modern Yoga were Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, and his disciple K. Pattabhi Jois, who introduced his style of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga in 1948. Most systems of Hatha Yoga which developed from the 1960s in the "yoga boom" in the West are derived from Jois' system.

Reception in the West

Yoga came to the attention of an educated western public in the mid 19th century along with other topics of Hindu philosophy. The first Hindu teacher to actively advocate and disseminate aspects of Yoga to a western audience was Swami Vivekananda, who toured Europe and the United States in the 1890s.

In the West, the term "yoga" is today typically associated with Hatha Yoga and its asanas (postures) or as a form of exercise. In the 1960s, western interest in Hindu spirituality reached its peak, giving rise to a great number of Neo-Hindu schools specifically advocated to a western public. Among the teachers of Hatha yoga who were active in the west in this period were B.K.S. Iyengar, K. Pattabhi Jois, and Swami Vishnu-devananda, and Swami Satchidananda. A second "yoga boom" followed in the 1980s, as Dean Ornish, a follower of Swami Satchidananda, connected yoga to heart health, legitimizing yoga as a purely physical system of health exercises outside of counter culture or esotericism circles, and unconnected to a religious denomination.

There has been an emergence of studies investigating yoga as a complementary intervention for cancer patients. Yoga is used for treatment of cancer patients to decrease depression, insomnia, pain, and fatigue and increase anxiety control. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs include yoga as a mind-body technique to reduce stress. A study found that after seven weeks the group treated with yoga reported significantly less mood disturbance and reduced stress compared to the control group. Another study found that MBSR had showed positive effects on sleep anxiety, quality of life, and spiritual growth.

Schizophrenia has also fallen subject to yoga studies. Yoga's ability to improve cognitive functions and reduce stress makes it appealing in the treatment of schizophrenia because of its association with cognitive deficits and stress related relapse. In one study, at the end of four months those patients treated with yoga were better in their social and occupational functions and quality of life.

The three main focuses of Hatha yoga (exercise, breathing, and meditation) make it beneficial to those suffering from heart disease. Overall, studies of the effects of yoga on heart disease suggest that yoga may reduce high blood pressure, improve symptoms of heart failure, enhance cardiac rehabilitation, and lower cardiovascular risk factors.

Long-term yoga practitioners in the United States have reported musculoskeletal and mental health improvements, as well reduced symptoms of asthma in asthmatics. Regular yoga practice increases brain GABA levels and is shown to improve mood and anxiety more than other metabolically matched exercises, such as jogging or walking. Implementation of the Kundalini Yoga Lifestyle has shown to help substance abuse addicts increase their quality of life according to psychological questionnaires like the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale and the Quality of Recovery Index.

Yoga compared with other systems of meditation

Tantra

Tantrism is a practice that is supposed to alter the relation of its practitioners to the ordinary social, religious, and logical reality in which they live. Through Tantric practice, an individual perceives reality as maya, illusion, and the individual achieves liberation from it. Both Tantra & Yoga offer paths that relieve a person from depending on the world. Where Yoga relies on progressive restriction of inputs from outside; Tantra relies on transmutation of all external inputs so that one is no longer dependent on them, but can take them or leave them at will. They both make a person independent. This particular path to salvation among the several offered by Hinduism, links Tantrism to those practices of Indian religions, such as yoga, meditation, and social renunciation, which are based on temporary or permanent withdrawal from social relationships and modes.As Robert Svoboda attempts to summarize the three major paths of the Vedic knowledge, he exclaims:

During tantric practices and studies, the student is instructed further in meditation technique, particularly chakra meditation. This is often in a limited form in comparison with the way this kind of meditation is known and used by Tantric practitioners and yogis elsewhere, but is more elaborate than the initiate's previous meditation. It is considered to be a kind of Kundalini Yoga for the purpose of moving the Goddess into the chakra located in the "heart", for meditation and worship.

Buddhism

Even though the roots of Yoga lie in early Buddhism and its interaction with Vedanta, Buddhist meditation or dhyana in the medieval period took a separate development from Yoga as laid down by Patanjali and its descendants.

Zen Buddhism

Zen (the name of which derives from the Sanskrit "dhyaana" via the Chinese "ch'an") is a form of Mahayana Buddhism. The Mahayana school of Buddhism is noted for its proximity with Yoga. In the west, Zen is often set alongside Yoga; the two schools of meditation display obvious family resemblances. This phenomenon merits special attention since the Zen Buddhist school of meditation has some of its roots in yogic practices. Certain essential elements of Yoga are important both for Buddhism in general and for Zen in particular.

Tibetan Buddhism

Yoga is central to Tibetan Buddhism. In the Nyingma tradition, the path of meditation practice is divided into nine yanas, or vehicles, which are said to be increasingly profound. The last six are described as "yoga yanas": "Kriya yoga," "Upa yoga," "Yoga yana," "Mahā yoga," "Anu yoga" and the ultimate practice, "Ati yoga." The Sarma traditions also include Kriya, Upa (called "Charya"), and Yoga, with the Anuttara yoga class substituting for Mahayoga and Atiyoga.Other tantra yoga practices include a system of 108 bodily postures practiced with breath and heart rhythm. The Nyingma tradition also practices Yantra yoga (Tib. "Trul khor"), a discipline that includes breath work (or pranayama), meditative contemplation and precise dynamic movements to centre the practitioner. The body postures of Tibetan ancient yogis are depicted on the walls of the Dalai Lama's summer temple of Lukhang. A semi-popular account of Tibetan Yoga by Chang (1993) refers to caṇḍalī (Tib. "tummo"), the generation of heat in one's own body, as being "the very foundation of the whole of Tibetan Yoga." Chang also claims that Tibetan Yoga involves reconciliation of apparent polarities, such as prana and mind, relating this to theoretical implications of tantrism.

Christian meditation

Some Christians integrate yoga and other aspects of Eastern spirituality with Christian prayer and meditation. This has been attributed to a desire to experience God in a more complete way. The Roman Catholic Church, and some other Christian organizations have expressed concerns and disapproval with respect to some eastern and New Age practices that include yoga and meditation.

In 1989 and 2003, the Vatican issued two documents: Aspects of Christian meditation and "A Christian reflection on the New Age," that were mostly critical of eastern and New Age practices. The 2003 document was published as a 90 page handbook detailing the Vatican's position. The Vatican warned that concentration on the physical aspects of meditation "can degenerate into a cult of the body" and that equating bodily states with mysticism "could also lead to psychic disturbance and, at times, to moral deviations." Such concerns can be traced to the early days of Christianity, when the church opposed the gnostics' belief that salvation came not through faith but through a mystical inner knowledge.

The letter also says, "one can see if and how [prayer] might be enriched by meditation methods developed in other religions and cultures" but maintains the idea that "there must be some fit between the nature of [other approaches to] prayer and Christian beliefs about ultimate reality."

Some fundamentalist Christian organizations consider yoga practice to be incompatible with their religious background and therefore a non-Christian religious practice. It is also considered a part of the New Age movement and therefore inconsistent with Christianity.

Sufism

The development of Sufism was considerably influenced by Indian yogic practises, where they adapted both physical postures (asanas) and breath control (pranayama). The ancient Indian yogic text Amritakunda ("Pool of Nectar)" was translated into Arabic and Persian as early as the 11th century. Several other yogic texts were appropriated by Sufi tradition, but typically the texts juxtapose yoga materials alongside Sufi practices without any real attempt at integration or synthesis. Yoga became known to Indian Sufis gradually over time, but engagement with yoga is not found at the historical beginnings of the tradition.Malaysia's top Islamic body in 2008 passed a fatwa, which is legally non-binding, against Muslims practicing yoga, saying it had elements of "Hindu spiritual teachings" and that its practice was blasphemy and is therefore haraam. Muslim yoga teachers in Malaysia criticized the decision as "insulting." Sisters in Islam, a women's rights group in Malaysia, also expressed disappointment and said that its members would continue with their yoga classes.

The fatwa states that yoga practiced only as physical exercise is permissible, but prohibits the chanting of religious mantras, and states that teachings such as the uniting of a human with God is not consistent with Islamic philosophy. In a similar vein, the Council of Ulemas, an Islamic body in Indonesia, passed a fatwa banning yoga on the grounds that it contains "Hindu elements" These fatwas have, in turn, been criticized by Darul Uloom Deoband, a Deobandi Islamic seminary in India.

In May 2009, Turkey's head of the Directorate of Religious Affairs, Ali Bardakoğlu, discounted personal development techniques such as yoga as commercial ventures that could lead to extremism. His comments were made in the context of yoga possibly competing with and eroding participation in Islamic practice.

The only sect of the Islam community that has successfully incorporated yoga into its practice is the Jogi Faqir, whose followers are Muslim converts from the Hindu Jogicaste.

References

Notes

Bibliography

(fourth revised & enlarged edition).

Further reading

External links

Category:Yoga styles Category:Indian philosophy Category:Sanskrit words and phrases Category:Hindu philosophical concepts Category:Hindu philosophy Category:Meditation Category:Mind-body interventions Category:Spiritual practice Category:Exercise

af:Joga als:Yoga ar:يوجا an:Yoga az:Yoqa bn:যোগ (হিন্দুধর্ম) be:Ёга be-x-old:Ёга bo:ཡོ་ག bs:Joga br:Yoga bg:Йога ca:Ioga cs:Jóga cy:Yoga da:Yoga de:Yoga et:Jooga el:Γιόγκα es:Yoga eo:Jogo eu:Yoga fa:یوگا fr:Yoga gl:Ioga gu:યોગ ko:요가 hy:Յոգա hi:योग hr:Joga id:Yoga ia:Yoga is:Jóga it:Yoga he:יוגה jv:Yoga kn:ಯೋಗ ka:იოგა rw:Yoga la:Yoga lv:Joga lt:Joga hu:Jóga mk:Јога ml:യോഗം mr:योग ms:Yoga mwl:Ioga my:ယောဂကျင့်စဥ် nl:Yoga ne:योग new:योग ja:ヨーガ no:Yoga nn:Yoga oc:Iòga pnb:یوگا pl:Joga pt:Ioga ro:Yoga qu:Yoga rue:Йоґа ru:Йога sah:Йога sa:योग sq:Joga si:යෝග simple:Yoga sk:Joga sl:Joga sr:Joga sh:Joga fi:Jooga sv:Yoga tl:Yoga ta:யோகக் கலை te:యోగా th:โยคะ tg:Йога tr:Yoga uk:Йога ur:یوگا vi:Yoga fiu-vro:Jooga war:Yoga yi:יאגא zh:瑜伽This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

![Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America[105] and is also credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the end of the 19th century.[106] Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America[105] and is also credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the end of the 19th century.[106]](http://web.archive.org./web/20111120232754im_/http://cdn0.wn.com/pd/c6/0a/67a81c8988da48963bf4d5093699_small.jpg)