- About WN

- Contact

- Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- © 2011 World News Inc., all Rights Reserved

-

AOL

AOL Inc. (), formerly known as America Online and logo typeset as "Aol.", is an American global Internet services and media company. AOL is headquartered at 770 Broadway in New York. Founded in 1983 as Control Video Corporation, it has franchised its services to companies in several nations around the world or set up international versions of its services.

http://wn.com/AOL -

Chris Lewis (Usenet)

Chris Lewis is a Canadian expert on Usenet and spam. He is perhaps best known for his work in writing and running auto-cancelers for newsgroup spam, and his help in implementing (and avoiding the need for) UDPs. He is employed by Nortel/BNR and helps maintain the Ottawa-Carleton Unix Users Group (Ocunix [http://www.ocuug.on.ca/]).

http://wn.com/Chris_Lewis_(Usenet) -

Gene Spafford

Eugene Howard Spafford (born 1956), commonly known as Gene Spafford or Spaf, is a professor of computer science at Purdue University and a leading computer security expert.

http://wn.com/Gene_Spafford -

Geoff Collyer

Geoff Collyer is a Canadian computer scientist. He is the senior author of C News, a protocol-neutral news transport, and the designer of NOV, the News Overview database (article index) used by all modern newsreaders.

http://wn.com/Geoff_Collyer -

Kai Puolamäki

Kai Puolamäki is a Finnish physicist and Internet activist. He has been a vocal spokesman of the Finnish anti-copyright movement.

http://wn.com/Kai_Puolamäki -

Linus Torvalds

Linus Benedict Torvalds (; born December 28, 1969 in Helsinki, Finland) is a Finnish American software engineer, best known for having initiated the development of the Linux kernel and git revision control system. He later became the chief architect of the Linux kernel, and now acts as the project's coordinator.

http://wn.com/Linus_Torvalds -

Marc Andreessen

Marc Andreessen (born July 10, 1971) is an investor, startup coach, blogger, and a multi-millionaire software engineer best known as co-author of Mosaic, the first widely-used web browser, and co-founder of Netscape Communications Corporation. He was the chair of Opsware, a software company he founded originally as Loudcloud, when it was acquired by Hewlett-Packard. He is also a co-founder of Ning, a company which provides a platform for social-networking websites. On June 30, 2008, Facebook announced that he had joined their Board of Directors. On September 30, 2008, it was announced that he had joined the Board of Directors of eBay, and on September 17, 2009, it was announced he had been named to the board of HP. Andreessen is a frequent keynote speaker and guest at Silicon Valley conferences.

http://wn.com/Marc_Andreessen -

Mary Ann Horton

Mary Ann Horton, formerly Mark R. Horton (born November 21, 1955), is a Usenet and Internet pioneer. Horton contributed to Berkeley UNIX (BSD), including the vi editor and terminfo database, and led the growth of Usenet in the 1980s.

http://wn.com/Mary_Ann_Horton -

Rich Salz

Rich Salz is currently the technical lead for the XML appliance products at IBM. He came to IBM when he was Chief Security Officer of DataPower, which was acquired by IBM in 2005.

http://wn.com/Rich_Salz -

Steve Bellovin

http://wn.com/Steve_Bellovin -

Steven McGeady

Steven McGeady is a former Intel executive best known as a witness in the Microsoft antitrust trial. His notes contained colorful quotes by Microsoft executives threatening to "cut off Netscape's air supply" and Bill Gates' guess that "this anti-trust thing will blow over". Attorney David Boies said that McGeady's testimony showed him to be "an extremely conscientious, capable and honest witness," while Microsoft portrayed him as someone with an "axe to grind." McGeady left Intel in 2000, but later again gained notoriety for defending his former employee Mike Hawash after his arrest on federal terrorism charges. He is a member of the Reed College Board of Trustees and the PNCA Board of Governors, and lives in Portland, Oregon.

http://wn.com/Steven_McGeady -

Tim Berners-Lee

Sir Timothy John "Tim" Berners-Lee, OM, KBE, FRS, FREng, FRSA (born 8 June 1955, also known as "TimBL"), is a British engineer and computer scientist and MIT professor credited with inventing the World Wide Web, making the first proposal for it in March 1989. On 25 December 1990, with the help of Robert Cailliau and a young student at CERN, he implemented the first successful communication between an HTTP client and server via the Internet.

http://wn.com/Tim_Berners-Lee

-

Japan

Japan (日本 Nihon or Nippon), officially the State of Japan ( or Nihon-koku), is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south. The characters that make up Japan's name mean "sun-origin" (because it lies to the east of nearby countries), which is why Japan is sometimes referred to as the "Land of the Rising Sun".

http://wn.com/Japan -

Malta

Malta , officially the Republic of Malta (), is a southern European country and consists of an archipelago situated centrally in the Mediterranean, 93 km south of Sicily and 288 km east of Tunisia, with the Strait of Gibraltar 1,826 km to the west and Alexandria 1,510 km to the east.

http://wn.com/Malta -

Microsoft

Microsoft Corporation is a public multinational corporation headquartered in Redmond, Washington, USA that develops, manufactures, licenses, and supports a wide range of products and services predominantly related to computing through its various product divisions. Established on April 4, 1975 to develop and sell BASIC interpreters for the Altair 8800, Microsoft rose to dominate the home computer operating system (OS) market with MS-DOS in the mid-1980s, followed by the Microsoft Windows line of OSs. The ensuing rise of stock in the company's 1986 initial public offering (IPO) made an estimated four billionaires and 12,000 millionaires from Microsoft employees. Microsoft would come to dominate other markets as well, notably the office suite market with Microsoft Office.

http://wn.com/Microsoft -

State of New York

http://wn.com/State_of_New_York -

United States

The United States of America (also referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district. The country is situated mostly in central North America, where its forty-eight contiguous states and Washington, D.C., the capital district, lie between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The state of Alaska is in the northwest of the continent, with Canada to the east and Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. The state of Hawaii is an archipelago in the mid-Pacific. The country also possesses several territories in the Caribbean and Pacific.

http://wn.com/United_States

- alt.* hierarchy

- Andrew Cuomo

- AOL

- ARPANET

- ASCII

- B News

- backup

- Base64

- Big 8 (Usenet)

- Binaries

- binary file

- Binhex

- bit

- blog

- BOO (encoding)

- Bourne shell

- Breidbart Index

- BTOA

- C News

- child pornography

- Chris Lewis (Usenet)

- CNet

- computer network

- Computer World

- Control_message

- Crossposting

- David Wiseman

- Deja News

- DejaNews

- DMCA

- Duke University

- EasyNews

- Eternal September

- FAQ

- Fidonet

- fine art

- Flaming (Internet)

- flooding algorithm

- front-end

- Gene Spafford

- Geoff Collyer

- Gigabyte

- Godwin's Law

- Google Groups

- Google News

- Great Renaming

- Henry Spencer

- Index term

- inter-server

- Internet

- Internet forum

- InterNetNews

- JANET(UK)

- Japan

- jargon

- Jon Herlocker

- Kai Puolamäki

- kill file

- Linus Torvalds

- Linux

- List of newsgroups

- literature

- mailing list

- Malta

- Marc Andreessen

- Mark Horton

- Mary Ann Horton

- metadata (computing)

- Microsoft

- MIME

- Mosaic browser

- MSTing

- New England

- news client

- news server

- newsgroup

- Newsreader (Usenet)

- Outlook Express

- Parchive

- PC Magazine

- PC World (magazine)

- peer-to-peer

- philosophy

- RAR

- Request for Comments

- Rich Salz

- Ronda Hauben

- Scorefile

- Secure Sockets Layer

- Serdar Argic

- SMTP

- software

- spam (electronic)

- Sporgery

- Sprint Nextel

- State of New York

- Steve Bellovin

- Steven McGeady

- talk.origins

- TechCrunch

- Terabyte

- The Register

- Threaded discussion

- Tim Berners-Lee

- Time Warner Cable

- Tom Truscott

- Troll (Internet)

- uBackup

- United States

- Unix

- usenet backup

- Usenet cabal

- Usenet Death Penalty

- Usenet II

- USENIX

- USR encoding

- UUCP

- uuencode

- Wackyparsing

- web browser

- World Wide Web

- X-No-Archive

- X.25

- Xxencode

- yEnc

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:23

- Published: 22 Aug 2007

- Uploaded: 11 Oct 2011

- Author: lockergnome

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 6:40

- Published: 21 Feb 2008

- Uploaded: 19 Oct 2011

- Author: mobilephone2003

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:16

- Published: 17 Apr 2010

- Uploaded: 17 Oct 2011

- Author: al7barxbox360

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:28

- Published: 02 Aug 2010

- Uploaded: 17 Sep 2011

- Author: lifehacker

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 5:06

- Published: 31 May 2011

- Uploaded: 03 Aug 2011

- Author: THEsaleGURU

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:11

- Published: 06 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 16 Oct 2011

- Author: Usenetguides

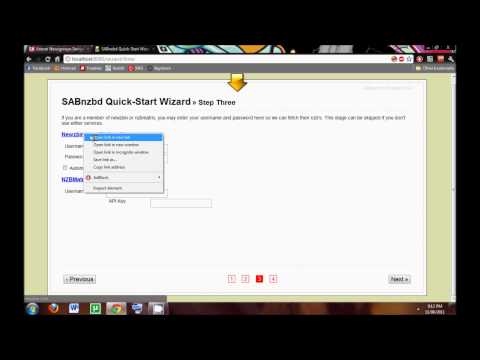

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:33

- Published: 15 Dec 2009

- Uploaded: 26 Aug 2011

- Author: UsenetReviewz

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 2:41

- Published: 03 May 2011

- Uploaded: 18 May 2011

- Author: MrTechnofo

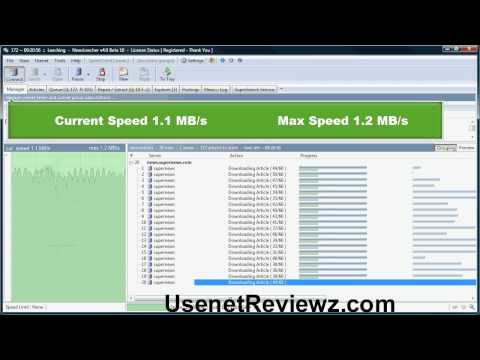

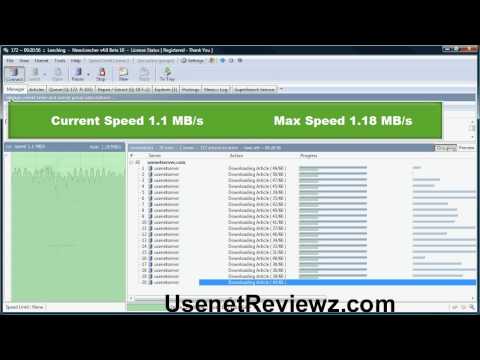

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:17

- Published: 14 Dec 2009

- Uploaded: 04 Oct 2011

- Author: UsenetReviewz

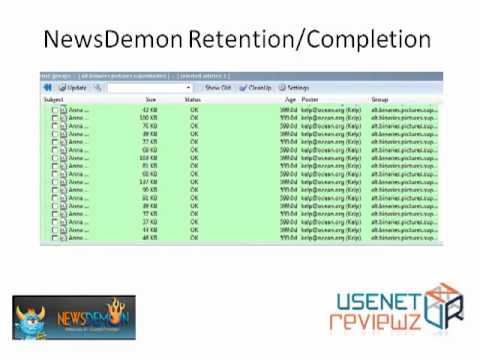

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:14

- Published: 31 Mar 2011

- Uploaded: 16 Apr 2011

- Author: UsenetReviewz

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:06

- Published: 15 Jul 2010

- Uploaded: 08 Jul 2011

- Author: sweetme285

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 1:25

- Published: 27 Oct 2010

- Uploaded: 13 Sep 2011

- Author: giganewsvideos

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 3:11

- Published: 24 Jan 2011

- Uploaded: 25 May 2011

- Author: EasynewsUsenet

- Order: Reorder

- Duration: 4:03

- Published: 09 May 2011

- Uploaded: 07 Oct 2011

- Author: fastusenet

-

Gadhafi body stashed in shopping center freezer

Detroit news

Gadhafi body stashed in shopping center freezer

Detroit news

-

Israel, Libya, U.S. and Pseudo-News and Events

WorldNews.com

Israel, Libya, U.S. and Pseudo-News and Events

WorldNews.com

-

Calls for investigation of Gadhafi's violent death

Kypost

Calls for investigation of Gadhafi's violent death

Kypost

-

UN rights office urges probe into Gadhafi death

The Tribune San Luis Obispo

UN rights office urges probe into Gadhafi death

The Tribune San Luis Obispo

-

Thailand says floods may ease early next month

Denver Post

Thailand says floods may ease early next month

Denver Post

- A News

- alt.* hierarchy

- Andrew Cuomo

- AOL

- ARPANET

- ASCII

- B News

- backup

- Base64

- Big 8 (Usenet)

- Binaries

- binary file

- Binhex

- bit

- blog

- BOO (encoding)

- Bourne shell

- Breidbart Index

- BTOA

- C News

- child pornography

- Chris Lewis (Usenet)

- CNet

- computer network

- Computer World

- Control_message

- Crossposting

- David Wiseman

- Deja News

- DejaNews

- DMCA

- Duke University

- EasyNews

- Eternal September

- FAQ

- Fidonet

- fine art

- Flaming (Internet)

- flooding algorithm

- front-end

- Gene Spafford

- Geoff Collyer

- Gigabyte

- Godwin's Law

- Google Groups

- Google News

- Great Renaming

- Henry Spencer

- Index term

- inter-server

- Internet

- Internet forum

- InterNetNews

- JANET(UK)

- Japan

- jargon

- Jon Herlocker

size: 0.8Kb

size: 3.2Kb

size: 0.7Kb

size: 2.5Kb

size: 7.7Kb

size: 12.2Kb

Usenet is a worldwide distributed Internet discussion system. It developed from the general purpose UUCP architecture of the same name.

Duke University graduate students Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis conceived the idea in 1979 and it was established in 1980. Users read and post messages (called articles or posts, and collectively termed news) to one or more categories, known as newsgroups. Usenet resembles a bulletin board system (BBS) in many respects, and is the precursor to the various Internet forums that are widely used today. Usenet can be superficially regarded as a hybrid between email and web forums. Discussions are threaded, with modern news reader software, as with web forums and BBSes, though posts are stored on the server sequentially.

One notable difference between a BBS or web forum and Usenet is the absence of a central server and dedicated administrator. Usenet is distributed among a large, constantly changing conglomeration of servers that store and forward messages to one another in so-called news feeds. Individual users may read messages from and post messages to a local server operated by their Internet service provider, university, or employer.

Introduction

Usenet is one of the oldest computer network communications systems still in widespread use. It was conceived in 1979 and publicly established in 1980 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University, over a decade before the World Wide Web was developed and the general public got access to the Internet. It was originally built on the "poor man's ARPANET," employing UUCP as its transport protocol to offer mail and file transfers, as well as announcements through the newly developed news software such as A News. The name USENET emphasized its creators' hope that the USENIX organization would take an active role in its operation.The articles that users post to Usenet are organized into topical categories called newsgroups, which are themselves logically organized into hierarchies of subjects. For instance, [news:sci.math sci.math] and [news:sci.physics sci.physics] are within the sci hierarchy, for science. When a user subscribes to a newsgroup, the news client software keeps track of which articles that user has read.

In most newsgroups, the majority of the articles are responses to some other article. The set of articles which can be traced to one single non-reply article is called a thread. Most modern newsreaders display the articles arranged into threads and subthreads.

When a user posts an article, it is initially only available on that user's news server. Each news server, however, talks to one or more other servers (its "newsfeeds") and exchanges articles with them. In this fashion, the article is copied from server to server and (if all goes well) eventually reaches every server in the network. The later peer-to-peer networks operate on a similar principle; but for Usenet it is normally the sender, rather than the receiver, who initiates transfers. Some have noted that this seems an inefficient protocol in the era of abundant high-speed network access. Usenet was designed for the times when networks were much slower, and not always available. Many sites on the original Usenet network would connect only once or twice a day to batch-transfer messages in and out.

Usenet has significant cultural importance in the networked world, having given rise to, or popularized, many widely recognized concepts and terms such as "FAQ" and "spam".

The format and transmission of Usenet articles is similar to that of Internet e-mail messages. The difference between the two is that Usenet articles can be read by any user whose news server carries the group to which the message was posted, as opposed to email messages which have one or more specific recipients.

Today, Usenet has diminished in importance with respect to Internet forums, blogs and mailing lists. Usenet differs from such media in several ways: Usenet requires no personal registration with the group concerned; information need not be stored on a remote server; archives are always available; and reading the messages requires not a mail or web client, but a news client. The groups in alt.binaries are still widely used for data transfer.

ISPs, news servers, and newsfeeds

Many Internet service providers, and many other Internet sites, operate news servers for their users to access. ISPs that do not operate their own servers directly will often offer their users an account from another provider that specifically operates newsfeeds. In early news implementations, the server and newsreader were a single program suite, running on the same system. Today, one uses separate newsreader client software, a program that resembles an email client but accesses Usenet servers instead.Not all ISPs run news servers. A news server is one of the most difficult Internet services to administer well because of the large amount of data involved, small customer base (compared to mainstream Internet services such as email and web access), and a disproportionately high volume of customer support incidents (frequently complaining of missing news articles that are not the ISP's fault). Some ISPs outsource news operation to specialist sites, which will usually appear to a user as though the ISP ran the server itself. Many sites carry a restricted newsfeed, with a limited number of newsgroups. Commonly omitted from such a newsfeed are foreign-language newsgroups and the alt.binaries hierarchy which largely carries software, music, videos and images, and accounts for over 99 percent of article data.

There are also Usenet providers that specialize in offering service to users whose ISPs do not carry news, or that carry a restricted feed.

See also news server operation for an overview of how news systems are implemented.

Newsreader clients

Newsgroups are typically accessed with special client software that connects to a news server. Newsreader clients are available for all major operating systems. Modern mail clients or "communication suites" commonly also have an integrated newsreader. Often, however, these integrated clients are of low quality, compared to standalone newsreaders, and incorrectly implement Usenet protocols, standards and conventions. Many of these integrated clients, for example the one in Microsoft's Outlook Express, are disliked by purists because of their misbehavior.With the rise of the World Wide Web (WWW), web front-ends (web2news) have become more common. Web front ends have lowered the technical entry barrier requirements to that of one application and no Usenet NNTP server account. There are numerous websites now offering web based gateways to Usenet groups, although some people have begun filtering messages made by some of the web interfaces for one reason or another. Google Groups is one such web based front end and web browsers can access Google Groups via news: protocol links directly.

Moderated and unmoderated newsgroups

A minority of newsgroups are moderated, meaning that messages submitted by readers are not distributed directly to Usenet, but instead are emailed to the moderators of the newsgroup for approval. The moderator is to receive submitted articles, review them, and inject approved articles so that they can be properly propagated worldwide. Articles approved by a moderator must bear the Approved: header line. Moderators ensure that the messages that readers see in the newsgroup conform to the charter of the newsgroup, though they are not required to follow any such rules or guidelines. Typically, moderators are appointed in the proposal for the newsgroup, and changes of moderators follow a succession plan.Historically, a mod.* hierarchy existed before Usenet reorganization. Now, moderated newsgroups may appear in any hierarchy.

Usenet newsgroups in the Big-8 hierarchy are created by proposals called a Request for Discussion, or RFD. The RFD is required to have the following information: newsgroup name, checkgroups file entry, and moderated or unmoderated status. If the group is to be moderated, then at least one moderator with a valid email address must be provided. Other information which is beneficial but not required includes: a charter, a rationale, and a moderation policy if the group is to be moderated. Discussion of the new newsgroup proposal follows, and is finished with the members of the Big-8 Management Board making the decision, by vote, to either approve or disapprove the new newsgroup.

Unmoderated newsgroups form the majority of Usenet newsgroups, and messages submitted by readers for unmoderated newsgroups are immediately propagated for everyone to see. Minimal editorial content filtering vs propagation speed form one crux of the Usenet community. One little cited defense of propagation is canceling a propagated message, but few Usenet users use this command and in fact some news readers don't offer cancellation commands, in part because article storage expires in relatively short order anyway.

Creation of moderated newsgroups often becomes a hot subject of controversy, raising issues regarding censorship and the desire of a subset of users to form an intentional community.

Technical details

Usenet is a set of protocols for generating, storing and retrieving news "articles" (which resemble Internet mail messages) and for exchanging them among a readership which is potentially widely distributed. These protocols most commonly use a flooding algorithm which propagates copies throughout a network of participating servers. Whenever a message reaches a server, that server forwards the message to all its network neighbors that haven't yet seen the article. Only one copy of a message is stored per server, and each server makes it available on demand to the (typically local) readers able to access that server. The collection of Usenet servers has thus a certain peer-to-peer character in that they share resources by exchanging them, the granularity of exchange however is on a different scale than a modern peer-to-peer system and this characteristic excludes the actual users of the system who connect to the news servers with a typical client-server application, much like an email reader.RFC 850 was the first formal specification of the messages exchanged by Usenet servers. It was superseded by RFC 1036.

In cases where unsuitable content has been posted, Usenet has support for automated removal of a posting from the whole network by creating a cancel message, although due to a lack of authentication and resultant abuse, this capability is frequently disabled. Copyright holders may still request the manual deletion of infringing material using the provisions of World Intellectual Property Organization treaty implementations, such as the U.S. Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act.

On the Internet, Usenet is transported via the Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP) on TCP Port 119 for standard, unprotected connections and on TCP port 563 for SSL encrypted connections which is offered only by a few sites.

Organization

The major set of worldwide newsgroups is contained within nine hierarchies, eight of which are operated under consensual guidelines that govern their administration and naming. The current Big Eight are:

See also the Great Renaming.

The alt.* hierarchy is not subject to the procedures controlling groups in the Big Eight, and it is as a result less organized. However, groups in the alt.* hierarchy tend to be more specialized or specific—for example, there might be a newsgroup under the Big Eight which contains discussions about children's books, but a group in the alt hierarchy may be dedicated to one specific author of children's books. Binaries are posted in alt.binaries.*, making it the largest of all the hierarchies.

Many other hierarchies of newsgroups are distributed alongside these. Regional and language-specific hierarchies such as .*, .* and ne.* serve specific countries and regions such as Japan, Malta and New England. Companies administer their own hierarchies to discuss their products and offer community technical support. Microsoft has closed its newsserver as of June 2010, providing support for its products over forums now. Some users prefer to use the term "Usenet" to refer only to the Big Eight hierarchies; others include alt as well. The more general term "netnews" incorporates the entire medium, including private organizational news systems.

Informal sub-hierarchy conventions also exist. *.answers are typically moderated cross-post groups for FAQs. An FAQ would be posted within one group and a cross post to the *.answers group at the head of the hierarchy seen by some as a refining of information in that news group. Some subgroups are recursive—to the point of some silliness in alt.*.

Binary content

Usenet was originally created to distribute text content encoded in the 7-bit ASCII character set. With the help of programs that encode 8-bit values into ASCII, it became practical to distribute binary files as content. Binary posts, due to their size and often-dubious copyright status, were in time restricted to specific newsgroups, making it easier for administrators to allow or disallow the traffic.

The usenet is not only used to distribute (binary) content, but also to store backup data. This method is called usenet backup or uBackup.

The oldest widely used encoding method is uuencode, from the Unix UUCP package. In the late 1980s, Usenet articles were often limited to 60,000 characters, and larger hard limits exist today. Files are therefore commonly split into sections that require reassembly by the reader.

With the header extensions and the Base64 and Quoted-Printable MIME encodings, there was a new generation of binary transport. In practice, MIME has seen increased adoption in text messages, but it is avoided for most binary attachments. Some operating systems with metadata attached to files use specialized encoding formats. For Mac OS, both Binhex and special MIME types are used.

Other lesser known encoding systems that may have been used at one time were BTOA, XX encoding, BOO, and USR encoding.

In an attempt to reduce file transfer times, an informal file encoding known as yEnc was introduced in 2001. It achieves about a 30% reduction in data transferred by assuming that most 8-bit characters can safely be transferred across the network without first encoding into the 7-bit ASCII space.

The standard method of uploading binary content to Usenet is to first archive the files into RAR archives (for large files usually in 15 MB, 50 MB or 100 MB parts) then create Parchive files. Parity files are used to recreate missing data. This is needed often, as not every part of the files reaches a server. These are all then encoded into yEnc and uploaded to the selected binary groups.

Binary retention time

on March 3, 2008, and is an example of the massive retention capabilities of a commercial usenet server.]]Each newsgroup is generally allocated a certain amount of storage space for post content. When this storage has been filled, each time a new post arrives, old posts are deleted to make room for the new content. If the network bandwidth available to a server is high but the storage allocation is small, it is possible for a huge flood of incoming content to overflow the allocation and push out everything that was in the group before it. If the flood is large enough, the beginning of the flood will begin to be deleted even before the last part of the flood has been posted.

Binary newsgroups are only able to function reliably if there is sufficient storage allocated to a group to allow readers enough time to download all parts of a binary posting before it is flushed out of the group's storage allocation. This was at one time how posting of undesired content was countered; the newsgroup would be flooded with random garbage data posts, of sufficient quantity to push out all the content to be suppressed. This has been compensated by service providers allocating enough storage to retain everything posted each day, including such spam floods, without deleting anything.

The average length of time that posts are able to stay in the group before being deleted is commonly called the retention time. Generally the larger usenet servers have enough capacity to archive several weeks of binary content even when flooded with new data at the maximum daily speed available. A good binaries service provider must not only accommodate users of fast connections (3 megabit) but also users of slow connections (256 kilobit or less) who need more time to download content over a period of several days or weeks.

Major NSPs don't delete any articles less than a year old, resulting in a retention time of more than 700 days.

Legal issues

While binary newsgroups can be used to distribute completely legal user-created works, open-source software, and public domain material, some binary groups are used to illegally distribute commercial software, copyrighted media, and obscene materials.ISP-operated Usenet servers frequently block access to all alt.binaries.* groups to both reduce network traffic and to avoid related legal issues. Commercial Usenet service providers claim to operate as a telecommunications service, and assert that they are not responsible for the user-posted binary content transferred via their equipment. In the United States, Usenet providers can qualify for protection under the DMCA Safe Harbor regulations, provided that they establish a mechanism to comply with and respond to takedown notices from copyright holders.

Removal of copyrighted content from the entire Usenet network is a nearly impossible task, due to the rapid propagation between servers and the retention done by each server. Petitioning a Usenet provider for removal only removes it from that one server's retention cache, but not any others. It is possible for a special post cancellation message to be distributed to remove it from all servers, but many providers ignore cancel messages by standard policy, because they can be easily falsified and submitted by anyone. For a takedown petition to be most effective across the whole network, it would have to be issued to the origin server to which the content has been posted, but has not yet been propagated to other servers. Removal of the content at this early stage would prevent further propagation, but with modern high speed links, content can be propagated as fast as it arrives, allowing no time for content review and takedown issuance by copyright holders.

Establishing the identity of the person posting illegal content is equally difficult due to the trust-based design of the network. Like SMTP email, servers generally assume the header and origin information in a post is true and accurate. However, as in SMTP email, Usenet post headers are easily falsified so as to obscure the true identity and location of the message source. In this manner, Usenet is significantly different from modern P2P services; most P2P users distributing content are typically immediately identifiable to all other users by their network address, but the origin information for a Usenet posting can be completely obscured and unobtainable once it has propagated past the original server.

Also unlike modern P2P services, the identity of the downloaders is hidden from view. On P2P services a downloader is identifiable to all others by their network address. On Usenet, the downloader connects directly to a server, and only the server knows the address of who is connecting to it. Some Usenet providers do keep usage logs, but not all make this logged information casually available to outside parties such as the RIAA.

History

Newsgroup experiments first occurred in 1979. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis of Duke University came up with the idea as a replacement for a local announcement program, and established a link with nearby University of North Carolina using Bourne shell scripts written by Steve Bellovin. The public release of news was in the form of conventional compiled software, written by Steve Daniel and Truscott. In 1980, Usenet was connected to ARPANET through UC Berkeley which had connections to both Usenet and ARPANET. Michael Horton, the graduate student that set up the connection, began “feeding mailing lists from the ARPANET into Usenet” with the “fa” identifier. As a result, the number of people on Usenet increased dramatically; however, it was still a while longer before Usenet users could contribute to ARPANET. After 32 years, the USENET news service link at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (news.unc.edu) was finally retired on February 4th, 2011.

Network

UUCP networks spread quickly due to the lower costs involved, and the ability to use existing leased lines, X.25 links or even ARPANET connections. By 1983, the number of UUCP hosts had grown to 550, nearly doubling to 940 in 1984.As the mesh of UUCP hosts rapidly expanded, it became desirable to distinguish the Usenet subset from the overall network. A vote was taken at the 1982 USENIX conference to choose a new name. The name Usenet was retained, but it was established that it only applied to news. The name UUCPNET became the common name for the overall network.

In addition to UUCP, early Usenet traffic was also exchanged with Fidonet and other dial-up BBS networks. Widespread use of Usenet by the BBS community was facilitated by the introduction of UUCP feeds made possible by MS-DOS implementations of UUCP such as UFGATE (UUCP to FidoNet Gateway), FSUUCP and UUPC. The Network News Transfer Protocol, or NNTP, was introduced in 1985 to distribute Usenet articles over TCP/IP as a more flexible alternative to informal Internet transfers of UUCP traffic. Since the Internet boom of the 1990s, almost all Usenet distribution is over NNTP.

Software

Early versions of Usenet used Duke's A News software. At Berkeley an improved version called B News was produced by Matt Glickman and Mark Horton. With a message format that offered compatibility with Internet mail and improved performance, it became the dominant server software. C News, developed by Geoff Collyer and Henry Spencer at the University of Toronto, was comparable to B News in features but offered considerably faster processing. In the early 1990s, InterNetNews by Rich Salz was developed to take advantage of the continuous message flow made possible by NNTP versus the batched store-and-forward design of UUCP. Since that time INN development has continued, and other news server software has also been developed.

Public venue

Usenet was the initial Internet community and the place for many of the most important public developments in the commercial Internet. It was the place where Tim Berners-Lee announced the launch of the World Wide Web, where Linus Torvalds announced the Linux project, and where Marc Andreessen announced the creation of the Mosaic browser and the introduction of the image tag, which revolutionized the World Wide Web by turning it into a graphical medium.

Internet jargon and history

Many jargon terms now in common use on the Internet originated or were popularized on Usenet. Likewise, many conflicts which later spread to the rest of the Internet, such as the ongoing difficulties over spamming, began on Usenet.

Decline

Sascha Segan of PC Magazine said in 2008 "Usenet has been dying for years[...]" Segan said that some people pointed to the Eternal September in 1993 as the beginning of Usenet's decline. Segan said that the "eye candy" on the World Wide Web and the marketing funds spent by owners of websites convinced internet users to use profit-making websites instead of Usenet servers. In addition, DejaNews and Google News made conversations searchable, and Segan said that this removed the obscurity of previously obscure internet groups on Usenet. Segan explained that when pornographers and software pirates began putting large files on Usenet, by the late 1990s this caused Usenet disk space and traffic to increase. Internet service providers allocated space to Usenet libraries, and internet service providers questioned why they needed to host space for pornography and pirated software. Segan said that the hosting of porn and pirated software was "likely when Usenet became truly doomed" and "[i]t's the porn that's putting nails in Usenet's coffin."AOL discontinued Usenet access in 2005. When the State of New York opened an investigation on child pornographers who used Usenet, many ISPs dropped all Usenet access or access to the alt. hierarchy. Segan concluded "It's hard to completely kill off something as totally decentralized as Usenet; as long as two servers agree to share the NNTP protocol, it'll continue on in some fashion. But the Usenet I mourn is long gone[...]" In response, John Biggs of TechCrunch said "Is Usenet dead, as Sascha posits? I don’t think so. As long as there are folks who think a command line is better than a mouse, the original text-only social network will live on." Biggs added that while many internet service providers terminated access, "the real pros know where to go to get their angst-filled, nit-picking, obsessive fix."In May 2010, Duke University, whose implementation had kicked off Usenet more than 30 years earlier, decommissioned its Usenet server, citing low usage and rising costs.

Usenet traffic changes

Over time, the amount of Usenet traffic has steadily increased. the number of all text posts made in all Big-8 newsgroups averaged 1,800 new messages every hour, with an average of 25,000 messages per day. However, these averages are minuscule in comparison to the traffic in the binary groups. Much of this traffic increase reflects not an increase in discrete users or newsgroup discussions, but instead the combination of massive automated spamming and an increase in the use of .binaries newsgroups in which large files are often posted publicly. A small sampling of the change (measured in feed size per day) follows:

| style="text-align:right" | Daily Volume!!Date!!Source | ||

| style="text-align:right" | 4.5 GB | 1996-12 | Altopia.com |

| style="text-align:right" | 9 GB | 1997-07 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 12 GB | 1998-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 26 GB | 1999-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 82 GB | 2000-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 181 GB | 2001-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 257 GB | 2002-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 492 GB | 2003-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 969 GB | 2004-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.30 TB | 2004-09-30 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.38 TB | 2004-12-31 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.52 TB | 2005-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.34 TB | 2005-01-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.30 TB | 2005-01-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.81 TB | 2005-02-28 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 1.87 TB | 2005-03-08 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 2.00 TB | 2005-03-11 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 2.27 TB | 2006-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 2.95 TB | 2007-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 3.07 TB | 2008-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 3.80 TB | 2008-04-16 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 4.60 TB | 2008-11-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 4.65 TB | 2009-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 6.00 TB | 2009-12 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 5.42 TB | 2010-01 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 8.00 TB | 2010-09 | |

| style="text-align:right" | 7.52 TB | 2011-01 |

In 2008, Verizon Communications, Time Warner Cable and Sprint Nextel signed an agreement with Attorney General of New York Andrew Cuomo to shut down access to sources of child pornography. Time Warner Cable stopped offering access to Usenet. Verizon reduced its access to the "Big 8" hierarchies. Sprint stopped access to the alt.* hierarchies. AT&T; stopped access to the alt.binaries.* hierarchies. Cuomo never specifically named Usenet in his anti-child pornography campaign. David DeJean of PC World said that some worry that the ISPs used Cuomo's campaign as an excuse to end portions of Usenet access, as it is costly for the internet service providers. In 2008 AOL, which no longer offered Usenet access, and the four providers that responded to the Cuomo campaign were the five largest internet service providers in the United States; they had more than 50% of the U.S. ISP marketshare. On June 8, 2009, AT&T; announced that it would no longer provide access to the Usenet service as of July 15, 2009.

AOL announced that it would discontinue its integrated Usenet service in early 2005, citing the growing popularity of weblogs, chat forums and on-line conferencing. The AOL community had a tremendous role in popularizing Usenet some 11 years earlier.

In August, 2009, Verizon announced that it would discontinue access to Usenet on September 30, 2009. In April 2010, Cox Communications announced (via email) that it would discontinue Usenet service, effective June 30, 2010. JANET(UK) announced it will discontinue Usenet service, effective July 31, 2010, citing Google Groups as an alternative. Microsoft announced that it would discontinue support for its public newsgroups (msnews.microsoft.com) from June 1, 2010, offering web forums as an alternative.

Primary reasons cited for the discontinuance of Usenet service by general ISPs include the decline in volume of actual readers due to competition from blogs, along with cost and liability concerns of increasing proportion of traffic devoted to file-sharing and spam on unused or discontinued groups.

At the same time, active discussion traffic has shifted away from ISPs toward dedicated Usenet servers accessible via newsreader or via the Web. Other sites host and archive Usenet newsgroups geared to specific topics via web interface, such as compgroups.net for the comp. groups hierarchy.

Archives

Public archives of Usenet articles have existed since the early days of Usenet, such as the system created by Kenneth Almquist in late 1982. Distributed archiving of Usenet posts was suggested in November 1982 by Scott Orshan, who proposed that "Every site should keep all the articles it posted, forever." Also in November of that year, Rick Adams responded to a post asking "Has anyone archived netnews, or does anyone plan to?" by stating that he was, "afraid to admit it, but I started archiving most "useful" newsgroups as of September 18." In June of 1982, Gregory G. Woodbury proposed an "Automatic access to archives" system that consisted of "automatic answering of fixed-format messages to a special mail recipient on specified machines."In 1985, two news archiving systems and one RFC were posted to the net. The first system, called keepnews, by Mark M. Swenson of The University of Arizona, was described as "a program that attempts to provide a sane way of extracting and keeping information that comes over Usenet." The main advantage of this system was to allow users to mark articles as worthwhile to retain. The second system, YA News Archiver by Chuq Von Rospach, was similar to keepnews, but was "designed to work with much larger archives where the wonderful quadratic search time feature of the Unix ... becomes a real problem." The same Chuq Von Rospach in early 1985 posted a detailed RFC for "Archiving and accessing usenet articles with keyword lookup." This RFC described a program that could "generate and maintain an archive of usenet articles and allow looking up articles based on the article-id, subject lines, or keywords pulled out of the article itself." Also included was C code for the internal data structure of the system.

The desire to have a fulltext search index of archived news articles is not new either, one such request having been made in April 1991 by Alex Martelli who sought to "build some sort of keyword index for [the news archive]." In early May, Mr. Martelli posted a summary of his responses to the net, noting that the "most popular suggestion award must definitely go to 'lq-text' package, by Liam Quin, recently posted in alt.sources."

Today, the archiving of Usenet has led to a fear of loss of privacy. An archive simplifies ways to profile people. This has partly been countered with the introduction of the X-No-Archive: Yes header, which is itself seen as controversial.

Archives by Google Groups and DejaNews

Web-based archiving of Usenet posts began in 1995 at Deja News with a very large, searchable database. In 2001, this database was acquired by Google.

Google Groups hosts an archive of Usenet posts dating back to May 1981. The earliest posts, which date from May 1981 to June 1991, were donated to Google by the University of Western Ontario with the help of David Wiseman and others, and were originally archived by Henry Spencer at the University of Toronto's Zoology department. The archives for late 1991 through early 1995 were provided by Kent Landfield from the NetNews CD series and Jürgen Christoffel from GMD. The archive of posts from March 1995 onward was originally started by the company DejaNews (later Deja), which was purchased by Google in February 2001. Google began archiving Usenet posts for itself in August 2000. Already during the DejaNews era the archive had become a popular constant in Usenet culture, and remains so today.

See also

Usenet terms

Usenet history

Usenet administrators

Usenet as a whole has no administrators; each server administrator is free to do whatever pleases him or her as long as the end users and peer servers tolerate and accept it. Nevertheless, there are a few famous administrators:

Usenet celebrities

References

Further reading

External links

Category:Virtual communities Category:Computer-mediated communication Category:On-line chat Category:Internet protocols Category:Internet standards Category:Network-related software Category:Pre–World Wide Web online services Category:Wikipedia articles with ASCII art Category:History of the Internet

ar:يوزنت bs:Usenet br:Usenet ca:Usenet cs:Usenet de:Usenet es:Usenet eo:Usenet fa:یوزنت fr:Usenet ko:유즈넷 hi:यूज़नेट hr:Usenet id:Usenet ia:Usenet it:Usenet he:קבוצת דיון ms:Usenet nl:Usenet ja:ネットニュース no:Usenet pl:Usenet pt:Usenet ro:Usenet ru:Usenet simple:Usenet sk:Usenet sl:USENET sh:Usenet fi:Keskusteluryhmät sv:Usenet tr:Usenet uk:Usenet vi:Usenet zh:UsenetThis text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.