Werner Herzog, Playing the Villain

Why someone didn’t cast Werner Herzog as a supervillain before this is beyond me. Who could be more perfect?

Why someone didn’t cast Werner Herzog as a supervillain before this is beyond me. Who could be more perfect?

Not that I should expect anything better from the New York Daily News, but its opinion piece about Occupy Wall Street is utterly reprehensible:

Someone at Legal Insurrection stumbled into a truth somehow:

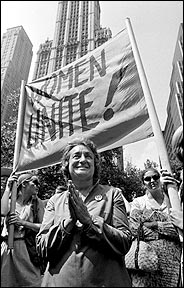

A common protest chant of the Occupy Wall Street crew and other radicals is “This is what democracy looks like!” – a trite, rhythmic expression of self-congratulation layered over an implication that they represent the true will of the people.

Contrary to every post on every conservative blog about the Tea Party, it turns out that massive demonstrations of angry partisans don’t necessarily represent the “true will” of “the people.” Will conservative bloggers remember that the next time one of their idols talks about “Real Americans” or claims to be “Taking My Country Back”?

James Atlas has a terrific essay in this past Sunday’s New York Times on how the higher education game is generating what he calls Super People — applicants with absurdly hyper-competent resumes, who clearly have been groomed since the age of three to Succeed in Life by their obsessive parents:

Graduate and professional school statistics are just as daunting. Dr. Bardes told me that he routinely interviewed students with perfect or near perfect grade point averages and SATs — enough to fill the class several times over. Last year 5,722 applicants competed for 101 places at Weill Cornell; the odds of getting in there are even worse than those of getting your 3-year-old into a New York City private school.

“Applicant pools are stronger and deeper,” concurs Stephen Singer, the former director of college counseling at Horace Mann, the New York City private school renowned for its driven students. “It used to be that if you were editor of the paper or president of your class you could get in almost anywhere,” Mr. Singer says. “Now it’s ‘What did you do as president? How did you make the paper special?’ Kids file stories from Bosnia or El Salvador on their summer vacations.” Such students are known in college admissions circles as “pointy” — being well-rounded doesn’t cut it anymore. You need to have a spike in your achievement chart.

Of course having a “spike in your achievement chart” doesn’t exactly come cheap:

Affluent families can literally buy a better résumé. “In a bad economy, the demographic shift has the potential to reinforce a socio-economic gap,” says Todd Breyfogle, who oversaw the honors program at the University of Denver and is now director of seminars at the Aspen Institute. “Only those families who can help their students be more competitive will have students who can get into elite institutions.”

Schools are now giving out less scholarship money in the tight economy, favoring students who can pay full freight. Meanwhile, Super People jet off on Mom and Dad’s dime to archaeological digs in the Negev desert, when they might once have opted to be counselors in training at Camp Shewahmegon for the summer. And the privilege of laboring as a volunteer in a day care center in Guatemala — “service learning,” as it’s sometimes called — doesn’t come cheap once you tote up the air fare, room and board.

Colleges collude in the push to upgrade talent. “It’s a huge industry,” Mr. Breyfogle says. “Harvard has a whole office devoted to preparing applicants for the Rhodes and Marshall scholarships.” At its worst, this kind of coaching results in candidates who are treated as what he calls “management projects.

”“They’ve been put in the hands of makeover experts who have a stake in making them look better than they are, leveraging their achievement,” Mr. Breyfogle says.

“We are concerned about that,” confirmed Jeff Rickey, head of admissions at St. Lawrence University, whom I tracked down at the National Association for College Admission Counseling conference in New Orleans. “If they joined a club, when did they join it? Maybe they play 15 instruments, but when they list them out, the amount of time they spent on each isn’t that much.” Mr. Breyfogle is also on the alert for résumé stuffing. “They’ve worked at an orphanage in Katmandu, but it turns out it was over Christmas break,” he gave as an example. “It’s easier to be amazing now.” All you need is money.

Ah yes, the wonders of our “meritocracy,” in which the cream rises inevitably to the top, hard work is rewarded, and the best and the brightest jet from Katmandu orphanages to Princeton eating clubs and 172 LSAT scores!

All this, as Atlas points out, is part and parcel of a society increasingly stratified along class lines, in which the rich get richer, and in the process gain ever-greater advantages in making sure that their progeny have every advantage in the race for those precious slots at the top colleges and professional schools (and from there the top firms and agencies and businesses etc etc).

At the moment American life features a big demographic problem, which is that the baby boomers have all the good jobs, and we’re not going away any time soon. This, more than the current dire state of the economy, is the long-term problem that the education establishment in general, and law schools in particular, must grapple with. It’s one thing to mock the person who “only” got into a Tier Three law school for being unable to get a job (although in fact that person has finished ahead of 97% of the population in the credentialing rat race), but what about the guy who had an A average at a good undergraduate school and a 167 on the LSAT, and finished in the top 20% of his class at George Washington, and can’t get a job? There are plenty of those people now too — because the baby boomers have all the good jobs.

What did that guy do wrong again? Oh right he should have “worked harder” and spent a couple of more holidays in college working on Guatemalan farm cooperatives, and gotten into NYU Law. Except a third of NYU’s third year class is now in trouble, and a lot of the rest of it is looking at big problems three to five years down the road, when they and their 200K loans get laid off by the mega-firms that hired them out of law school. Oh well I guess they should have “worked harder” and gotten into Yale. Because no matter what happens, the thing to remember is that if something goes wrong it’s your fault, or possibly your parents,’ but never ever the system’s, which is fundamentally fair and just if always amenable to some marginal tweaking to make it even better.

Atlas mentions another aspect of all this that deserves a separate essay:

And to clamber up there you need a head start. Thus the well-documented phenomenon of helicopter parents. In her influential book “Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety,” Judith Warner quotes a mom who gave up her career to be a full-time parent: “The children are the center of the household and everything goes around them. You want to do everything and be everything for them because this is your job now.” Bursting with pent-up energy, the mothers transfer their shelved career ambitions to their children. Since that book was published in 2005, the situation has only intensified. “One of my daughter’s classmates has a pilot’s license; 12-year-olds are taking calculus,” Ms. Warner said last week.

“This is your job now.” I think I’ve seen this movie before, and it didn’t have a happy ending.

I don’t want to devote a lot more time to someone who’s not going to run for president, but the overclass moral panic reaction to Chris Christie’s potential run does reveal some interesting things. First, the preferred line of the “Christie’ weight is relevant” brigade here seems to be the very familiar bigotry-once-removed argument. That is, “I’m not saying that I wouldn’t vote for a person of color/woman/LBGT/overweight person, but lots of other people wouldn’t, so we’d better confine ourselves to slender white guys.” Aside from the fact that this involves projection about 99% of the time, in the case of Christie (who did, after all, get elected governor of a blue state) there’s no actual evidence that it’s true. Although admittedly people who prefer to ascribe their bigotry to third parties will have some empirical evidence should an overweight woman seek a major party nomination. Since I’m not a reactionary, I’m not inclined to blithely accept this status quo either.

I would also note that this is completely irrelevant to the arguments made by Kinsley and Robinson. They didn’t argue that Christie couldn’t become president; they argued that his weight makes him unqualified to be president. Bigotry just doesn’t get a lot more stark. Christie’s size isn’t evidence of some moral failing, and as governor he’s been all too competent at achieving his ends. There are plenty of good reasons why Christie shouldn’t be president, but whether people have the guts to make the argument themselves or pretend to be discussing someone else this one is very dumb and very offensive.

See also. My favorite example of using the phrase “playing the race card” as a way of asserting without argument that racism (at least among white conservatives) can never exist is actually Michelle Malkin, who argues that the Post “tried to macaca Rick Perry.” Indeed, how could the media have “played the race card” by pointing it out when a politician who proudly wore the Treason in Defense of Slavery flag while growing up in California used a racial slur that had no possible meaning other than a racial slur? How unfair!

I’m not sure I’m the appropriate target for this anti-Romney hate spam, but I’ll dutifully pass along:

While rhetorician Mitt Romney charms his way through the 2012 Presidential Campaign, he is banking that you will believe what he “says” and not look to what his record demonstrates.

Let’s review his record regarding abortion under Romneycare:

- Ø On his 1994 campaign flyer, Romney lists “Retain a woman’s right to choose” as one of his foremost matters.

- Ø In 1994 the Boston Globe also reported Romney’s stance on the RU-486 abortion pill, quoting Romney as saying “I would favor having it available”.

- Ø During a debate in 1994, Romney stated “I believe that abortion should be safe and legal in this country”. He further stated “I believe that since Roe v. Wade has been the law for 20 years we should sustain and support it”.

- Ø Romney claimed in 2005 that while he was running for governor in 2002, was “personally pro-life” yet still had a pro-life “conversion” in 2004.

- Ø After his pro-life conversion based on embryonic stem cell research, Mitt stated that such research does not destroy human life, even though he believes life begins at conception and continued to support such research.

- Ø Mitt instituted a health care program in Massachusetts that includes a $50 co-pay for abortion at taxpayer’s expense, after his pro-life conversion.

- Ø Gave Planned Parenthood an instrumental role on the policy board in his Massachusetts healthcare plan, after his “pro-life conversion”.

- Ø Appointed a pro-choice judge, Matthew Nestor, to a lifetime appointment on a Massachusetts court, after his “pro-life conversion”.

Ooh, that smooth talking, baby killing Mitt Romney: We hates him so much!

I guess this is why so many people remain convinced that he can’t possibly win the GOP nomination. It’s sometimes argued that Senators make poor Presidential candidates because they have to engage in legislative compromise to the degree that they become poisonous to one constituency or another. In this cycle, it appears that governors are having the same problem on the Republican side; even Rick Perry is getting hit for pursuing the absolute minimum degree of relatively sane policies in order to make Texas function on a day-to-day basis. I suspect that Chris Christie will soon find himself subject to the Inquisition…

In the comments in the technological futurism/higher ed thread below, the “student as consumer model” is being debated. Marc Murc is fine with it:

College is fucking expensive, and as an adult student, the sole reason I went back is that I expect a return on my investment. I expect value for my money. And hey, the government considers college educations to be so valuable that they pay for lots of people to get’em.

If I’m not a consumer, what the hell am I?

I think this conversation often plays out in a pretty unproductive way. Many faculty (myself included) are tempted to respond by highlighting the differences between the academy and the marketplace, and lamenting the the logic of the marketplace encroaching in all areas of life. (Advanced versions of this line of thought might mention the Habermasian distinction between systems and lifeworld). I don’t entirely disagree with this, but I certainly don’t blame students for finding it maddening.

There is a sense, obviously, in which students are analogous to consumers, and there’s no point in denying that. The enrollment management office is engaged in a form of sales, and the faculty are part of the overall package that’s being sold. There is no denying they are purchasing something, and we’ve got an obligation to provide quality instruction in return. I think this needs to be acknowledged in order to narrow in on what’s wrong with the ‘consumer model’ as it’s frequently sold to many faculty, in practical rather than theoretical terms.

The problem with the consumer model arises when the “customer is always right” mentality (they want their widgets purple! With salsa dispensers!) is pursued. One reason it doesn’t work is that the outcomes we’re pursuing often make it difficult to identify when the student/consumer should be listened to. To take an example, I have a writing assignment in a course I regularly teach that students routinely and strenuously dislike (in ways that go beyond the generic complaint of “too hard/too much work”); they complain about it when it’s assigned and as they’re working on it. I can see its pedagogical value, because I’ve used it several times and know it generally works, so it stick with it. Many students (but by no means all) come to recognize the value of the assignment by the end of the term. There are definitely versions of the consumer model floating around that suggest we gather and respond to student feedback mid-semester. Mid-semester feedback can be valuable, but not indiscriminately so.

To take another example, in accordance with the consumer model we recently instituted an exit survey of graduating majors. The two most robust findings from the survey about classroom instruction were: 1. Students overwhelming said they wanted more instruction and training in public speaking, and 2. They overwhelmingly said that the least valuable part of the classroom experience is listening to other students speak. The consumer model offers little guidance here. I happen to agree on #1, but it can’t be pursued if we’re using the consumer model in real time and responding to #2.

These examples raise a question: if we are to treat the student as a consumer, the question is when do we treat the student as a consumer. At the beginning of the semester? Mid-semester? End of the term? At graduation? (The metaphor as applied to retail would suggest ‘whenever they pipe up and complain’ is the correct time). Taking ‘consumer feedback’ at each moment potentially works against the others. The model imported from retail would suggest we do what we can to keep our customers happy, comfortable and satisfied at every point in time. Indeed, in many consumer contexts, this is considerably more important than making sure consumers get the best possible product.

To seek out and judiciously use student feedback to improve teaching and instruction is potentially valuable, and there are other ways in which the model might be helpful as well. But the way it’s being sold to–and pushed on–classroom instructors in many cases would have us chasing our tails in obviously unproductive ways, that are of no benefit to students in the long run, and make little pedagogical sense. Students are undeniably consumers in some real sense of the term, but in fundamentally different ways than we normally think of the term. The question is not whether the metaphor is ‘correct’ in some sense, but to what use the metaphor is put. It can potentially be put to good use, but often isn’t.

This Bill Keller piece at the Times discusses Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun’s plan to eliminate the traditional university through technology, offering a future of higher education for at all at (theoretically) low prices, delivered by a very few highly paid professors with huge cadres of graduate students to grade the thousands of exams.

It seems that technology is the one part of our lives in which we are seen to have no control. Marxists used to talk about Man in History (with a capital H), of people caught up in forces bigger than they were leading humanity to an inevitable, predestined future. Of course, no one thinks that anymore about politics or history or economics, but they sure think very similarly when it comes to technology. The reaction to the discussion on self-checkout machines at grocery stores that I and djw started reeks of this, to some extent in comments, but more specifically in the longer posts people wrote on their own sites. Yglesias weighed in, inspiring Peter Frase’s piece of technological utopianism that djw responded to in length the other day. Frase, and I think to a lesser extent Yglesias, envisions an ideal world where technology frees us from drudgery work like checking out groceries, hoping that a social safety net will protect those that can’t adjust.

Of course, that safety net is going away rapidly. But hey, we can’t resist this technology. After all, technological innovation only helps the working person, right? As djw excoriates Frase for saying, “The decoupling of rising productivity from rising fortunes for workers is, after all, only a phenomenon of the past 30 years.” Oh, is that all? Only the majority of the working career of an adult who came of age in 1980? And it’s not like there’s any sign that this isn’t going to become 50 or 60 years, at the very least.

But then, it’s not like Frase is the only technological utopian out there. My students buy this whole hog. They think they are riding the wave of a paradise of new technological achievements that will make our lives easier and better. They have a very hard time figuring out that technology can sometimes have unexpected bad consequences, not to mention fully intended bad consequences like putting people out of work. I can’t really speak for other countries, though clearly societies like Japan and South Korea share similar love of technological innovation, but this blind faith in technology is deeply embedded in what it means to be an American, going back to the early 19th century and the rise of canals and railroads at the very least.

So evidently, humans have no agency to accept or reject technology. We can either embrace it wholeheartedly and ideologically or we can be called “Luddites,” which several people rightfully pointed out is a term completely disconnected from what actual Luddites stood for, pointlessly resisting an overwhelming force that will grind us under its unstoppable wheels.

While people like Sebastian Thrun are trying to apply this technological futurism to our entire lives, its more of a dream than reality at this point for higher education. Over a decade into its existence and supposed take-over of higher education, the impact of online courses have remained relatively limited. Lower-end schools rely on them as do schools developing courses for non-traditional students. But the big for-profit educational institutions have been a disaster, with students poorly served by them and their educational models. There’s not much evidence that the traditional 18-22 year old college student want this alternative to the traditional college experience, because college is so much more than just taking classes.

Of course, with the rapidly rising price of higher education, one wonders whether people might be forced into online courses, but that doesn’t make it a good thing. The evidence does not suggest that students learn better this way. On top of that, one wonders both why Thrun would want to outsource his own job (though no doubt he sees himself as one of the charismatic professors who would survive) and who these graduate students are who are going to manage courses with thousands of students. In a future of higher education with almost no chance of academic employment, why would people become graduate students? This is obviously an issue today as well, but the employment prospects would fall from slim but real enough that you can delude yourself to literally zero.

Thrun’s model also seems to neglect the skill-building exercises of the college classroom–how to write, how to comport oneself professionally, how to think critically, how to engage in a group discussion. This is not just socialization but skills people need to compete professionally.

But then Thrun’s model isn’t practical at all. It’s the model of a dreamer, someone who hopes that one day, we can offer higher education to all for very cheap in a world where robots will do everything and we will have zero employment. This is the technological future that we are all supposed to embrace or to sacrifice the future of human growth while we spend our days toiling away checking out people’s groceries. Evidently, we have no ability to resist this unstoppable technological force. We might as well start constructing our altars to the robot gods now. At least until we can create robots to do it for us for a fraction of the cost.

After doing this very thing, or more specifically saying that John Boehner playing golf with Barack Obama was like Benjamin Netanyahu playing golf with Adolf Hitler, ESPN has suspended Hank Williams, Jr. from doing his hideous Monday Night Football “Are You Ready for Some Football” intro bit.

As Hank Hill once said, “Hank Williams was the greatest country singer who ever lived. Hank Williams Jr. destroyed Monday Night Football.” Indeed.

Is it too much to hope for that Faith Hill turns out to be a Satanist or something and NBC kills her awful Sunday Night Football intro? This seems like a very reasonable thing to hope for to me.

Also, is everyone else as excited for Hank Jr.’s upcoming Senate bid from Tennessee?

Rick Perry continues to long for the golden age of Hammer v. Dagenhart.