- Order:

- Duration: 5:02

- Published: 24 Aug 2009

- Uploaded: 03 Aug 2011

- Author: reflect7

Marxism is an economic and socio-political worldview that contains within it a political ideology for how to change and improve society by implementing socialism. Originally developed in the early to mid 19th century by two German émigrés living in Britain, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Marxism is based upon a materialist interpretation of history. Taking the idea that social change occurs because of the struggle between different classes within society who are under contradiction one against the other, the Marxist analysis leads to the conclusion that capitalism, the currently dominant form of economic management, leads to the oppression of the proletariat, who not only make up the majority of the world's populace but who also spend their lives working for the benefit of the bourgeoisie, or the wealthy ruling class in society.

To correct this inequality between the bourgeoisie, who are the wealthy minority, and the proletariat, who are the poorer majority, Marxism advocates, and believes in the historical inevitability of, a proletarian revolution, when the proletariat take control of government, and then implement reforms to benefit their class, namely the confiscation of private property which is then taken under state control and run for the benefit of the people rather than for the interests of private profit. Such a system is socialism, although Marxists believe that eventually a socialist society would develop into an entirely classless system, which is known as communism in Marxist thought.

A Marxist understanding of history and of society has been adopted by academics studying in a wide range of disciplines, including archaeology, anthropology, media studies, political science, theater, history, sociological theory, cultural studies, education, economics, geography, literary criticism, aesthetics, critical psychology, and philosophy.

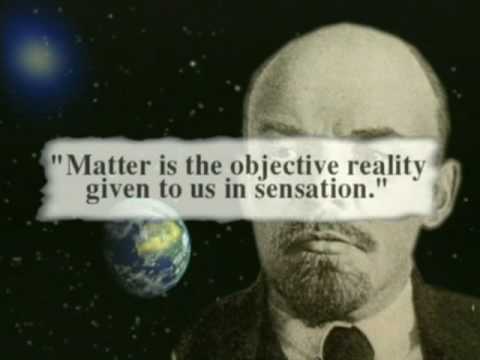

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, Marxist governments have taken power in a variety of nations across the world, and implemented socialist reforms. The first, and most powerful Marxist-run nation state was the Soviet Union, founded in 1922 following the Russian revolution of 1917. Several of its leaders, most notably Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin were also important Marxist theoreticians, formulating the theoretical trends of Marxism-Leninism, Trotskyism and Stalinism respectively. The other prominent Marxist power of the 20th century was the People's Republic of China, instituted in 1949 following the Chinese Civil War, and its first leader, Mao Zedong, was also a noted theoretician, developing Maoism. Today, a number of nations continue to be run by Marxist leaders, including Cuba, Nepal, large parts of India, and debatably Venezuela.

Karl Heinrich Marx (5 May 1818—14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political economist, and socialist revolutionary, who addressed the matters of alienation and exploitation of the working class, the capitalist mode of production, and historical materialism. He is famous for analysing history in terms of class struggle, summarised in the initial line introducing the Communist Manifesto (1848): “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. His ideas were influential in his time, and it was greatly expanded by the successful Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917 in Imperial Russia.

Friedrich Engels (28 November 1820–5 August 1895) was a 19th century German political philosopher and Karl Marx’s co-developer of communist theory. Marx and Engels met in September 1844; discovering that they shared like views of philosophy and socialism, they collaborated and wrote works such as Die heilige Familie (The Holy Family). After the French deported Marx from France in January 1845, Engels and Marx moved to Belgium, which then permitted greater freedom of expression than other European countries; later, in January 1846, they returned to Brussels to establish the Communist Correspondence Committee.

In 1847, they began writing The Communist Manifesto (1848), based upon Engels’ The Principles of Communism; six weeks later, they published the 12,000-word pamphlet in February 1848. In March, Belgium expelled them, and they moved to Cologne, where they published the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, a politically radical newspaper. Again, by 1849, they had to leave Cologne for London. The Prussian authorities pressured the British government to expel Marx and Engels, but Prime Minister Lord John Russell refused.

After Karl Marx’s death in 1883, Friedrich Engels became the editor and translator of Marx’s writings. With his Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884) — analysing monogamous marriage as guaranteeing male social domination of women, a concept analogous, in communist theory, to the capitalist class’s economic domination of the working class — Engels made intellectually significant contributions to feminist theory and Marxist feminism.

Different types of thinkers influenced the development of Classical Marxism; the primary influences derive from:

and secondary influences derive from:

The historical materialist theory of history, also synonymous to “the economic interpretation of history” (a coinage by Eduard Bernstein), looks for the causes of societal development and change in the collective ways humans use to make the means for living. The social features of a society (social classes, political structures, ideologies) derive from economic activity; “base and superstructure” is the metaphoric common term describing this historic condition.

The base and superstructure metaphor explains that the totality of social relations regarding “the social production of their existence” i.e. civil society forms a society’s economic base, from which rises a superstructure of political and legal institutions i.e. political society. The base corresponds to the social consciousness (politics, religion, philosophy, etc.), and it conditions the superstructure and the social consciousness. A conflict between the development of material productive forces and the relations of production provokes social revolutions, thus, the resultant changes to the economic base will lead to the transformation of the superstructure. This relationship is reflexive; the base determines the superstructure, in the first instance, and remains the foundation of a form of social organization which then can act again upon both parts of the base and superstructure, whose relationship is dialectical, not literal.

Marx considered that these socio-economic conflicts have historically manifested themselves as distinct stages (one transitional) of development in Western Europe.

# Primitive Communism: as in co-operative tribal societies. # Slave Society: a development of tribal progression to city-state; Aristocracy is born. # Feudalism: aristocrats are the ruling class; merchants evolve into capitalists. # Capitalism: capitalists are the ruling class, who create and employ the proletariat. # Socialism: workers gain class consciousness, and via proletarian revolution depose the capitalist dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, replacing it in turn with dictatorship of the proletariat through which the socialization of the means of production can be realized. # Communism: a classless and stateless society.

A person is exploited if he or she performs more labour than necessary to produce the goods that he consumes; likewise, a person is an exploiter if he or she performs less labour than is necessary to produce the goods that he consumes. Exploitation is a matter of surplus labour — the amount of labour one performs beyond what one receives in goods. Exploitation has been a socio-economic feature of every class society, and is one of the principal features distinguishing the social classes. The power of one social class to control the means of production enables its exploitation of the other classes.

In capitalism, the labour theory of value is the operative concern; the value of a commodity equals the total labour time required to produce it. Under that condition, surplus value (the difference between the value produced and the value received by a labourer) is synonymous with the term “surplus labour”; thus, capitalist exploitation is realised as deriving surplus value from the worker.

In pre-capitalist economies, exploitation of the worker was achieved via physical coercion. In the capitalist mode of production, that result is more subtly achieved; because the worker does not own the means of production, he or she must voluntarily enter into an exploitive work relationship with a capitalist in order to earn the necessities of life. The worker's entry into such employment is voluntary in that he or she chooses which capitalist to work for. However, the worker must work or starve. Thus, exploitation is inevitable, and the "voluntary" nature of a worker participating in a capitalist society is illusory.

Alienation denotes the estrangement of people from their humanity (German: Gattungswesen, “species-essence”, “species-being”), which is a systematic result of capitalism. Under capitalism, the fruits of production belong to the employers, who expropriate the surplus created by others, and so generate alienated labourers. Alienation objectively describes the worker’s situation in capitalism — his or her self-awareness of this condition is unnecessary.

The identity of a social class derives from its relationship to the means of production; Marx describes the social classes in capitalist societies:

Proletariat: “those individuals who sell their labour power, and who, in the capitalist mode of production, do not own the means of production“. The capitalist mode of production establishes the conditions enabling the bourgeoisie to exploit the proletariat because the workers’ labour generates a surplus value greater than the workers’ wages.

Class consciousness denotes the awareness — of itself and the social world — that a social class possesses, and its capacity to rationally act in their best interests; hence, class consciousness is required before they can effect a successful revolution.

Without defining ideology, Marx used the term to denote the production of images of social reality; according to Engels, “ideology is a process accomplished by the so-called thinker consciously, it is true, but with a false consciousness. The real motive forces impelling him remain unknown to him; otherwise it simply would not be an ideological process. Hence he imagines false or seeming motive forces”. Because the ruling class controls the society’s means of production, the superstructure of society, the ruling social ideas are determined by the best interests of said ruling class. In The German Ideology, “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is, at the same time, its ruling intellectual force”. Therefore, the ideology of a society is of most importance, because it confuses the alienated classes and so might create a false consciousness, such as commodity fetishism.

The term political economy originally denoted the study of the conditions under which economic production was organised in the capitalist system. In Marxism, political economy studies the means of production, specifically of capital, and how that is manifest as economic activity.

Marxists believe that a socialist society will be far better for the majority of the populace than its capitalist counterpart, for instance, prior to the Russian revolution of 1917, Lenin wrote that "The socialization of production is bound to lead to the conversion of the means of production into the property of society… This conversion will directly result in an immense increase in productivity of labour, a reduction of working hours, and the replacement of the remnants, the ruins of small-scale, primitive, disunited production by collective and improved labour."

Some Marxists have criticised Academic Marxism for being too detached from political Marxism. For instance, Zimbabwean Trotskyist Alex Callinicos, himself a professional academic, stated that "Its practitioners remind one of Narcissus, who in the Greek legend fell in love with his own reflection… Sometimes it is necessary to devote time to clarifying and developing the concepts that we use, but for Western Marxists this has become an end in itself. The result is a body of writings incomprehensible to all but a tiny minority of highly qualified scholars."

The following countries had governments at some point in the 20th century who at least nominally adhered to Marxism: Albania, Afghanistan, Angola, Benin, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Republic of Congo, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Ethiopia, Grenada, Hungary, Laos, Moldova, Mongolia, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, North Korea, Poland, Romania, Russia, the USSR and its republics, South Yemen, Yugoslavia, Venezuela, Vietnam. In addition, the Indian states of Kerala, Tripura and West Bengal have had Marxist governments, but change takes place in the government due to electoral process. Some of these governments such as in Venezuela, Nicaragua, Chile, Moldova and parts of India have been democratic in nature and maintained regular multiparty elections.

The 1917 October Revolution did help inspire a revolutionary wave over the years that followed, with the development of Communist Parties worldwide, but without success in the vital advanced capitalist countries of Western Europe. Socialist revolution in Germany and other western countries failed, leaving the Soviet Union on its own. An intense period of debate and stopgap solutions ensued, war communism and the New Economic Policy (NEP). Lenin died and Joseph Stalin gradually assumed control, eliminating rivals and consolidating power as the Soviet Union faced the events of the 1930s and its global crisis-tendencies. Amidst the geopolitical threats which defined the period and included the probability of invasion, he instituted a ruthless program of industrialization which, while successful, was executed at great cost in human suffering, including millions of deaths, along with long-term environmental devastation.

Modern followers of Leon Trotsky maintain that as predicted by Lenin, Trotsky, and others already in the 1920s, Stalin's "socialism in one country" was unable to maintain itself, and according to some Marxist critics, the USSR ceased to show the characteristics of a socialist state long before its formal dissolution.

In the 1920s the economic calculation debate between Austrian Economists and Marxist economists took place. The Austrians claimed that Marxism is flawed because prices could not be set to recognize opportunity costs of factors of production, and so socialism could not make rational decisions.

The Kuomintang party, a Chinese nationalist revolutionary party, had Marxist members who opposed the Chinese Communist Party. They viewed the Chinese revolution in different terms than the Communists, claiming that China already went past its feudal stage and in a stagnation period rather than in another mode of production. These marxists in the Kuomintang opposed the Chinese communist party ideology.

Following World War II, Marxist ideology, often with Soviet military backing, spawned a rise in revolutionary communist parties all over the world. Some of these parties were eventually able to gain power, and establish their own version of a Marxist state. Such nations included the People's Republic of China, Vietnam, Romania, East Germany, Albania, Cambodia, Ethiopia, South Yemen, Yugoslavia, Cuba, and others. In some cases, these nations did not get along. The most notable examples were rifts that occurred between the Soviet Union and China, as well as Soviet Union and Yugoslavia (in 1948), whose leaders disagreed on certain elements of Marxism and how it should be implemented into society.

Many of these self-proclaimed Marxist nations (often styled People's Republics) eventually became authoritarian states, with stagnating economies. This caused some debate about whether Marxism was doomed in practise or these nations were in fact not led by "true Marxists". Critics of Marxism speculated that perhaps Marxist ideology itself was to blame for the nations' various problems. Followers of the currents within Marxism which opposed Stalin, principally cohered around Leon Trotsky, tended to locate the failure at the level of the failure of world revolution: for communism to have succeeded, they argue, it needed to encompass all the international trading relationships that capitalism had previously developed.

The Chinese experience seems to be unique. Rather than falling under a single family's self-serving and dynastic interpretation of Marxism as happened in North Korea and before 1989 in Eastern Europe, the Chinese government - after the end of the struggles over the Mao legacy in 1980 and the ascent of Deng Xiaoping - seems to have solved the succession crises that have plagued self-proclaimed Leninist governments since the death of Lenin himself. Key to this success is another Leninism which is a NEP (New Economic Policy) writ very large; Lenin's own NEP of the 1920s was the "permission" given to markets including speculation to operate by the Party which retained final control. The Russian experience in Perestroika was that markets under socialism were so opaque as to be both inefficient and corrupt but especially after China's application to join the WTO this does not seem to apply universally.

The death of "Marxism" in China has been prematurely announced but since the Hong Kong handover in 1997, the Beijing leadership has clearly retained final say over both commercial and political affairs. Questions remain however as to whether the Chinese Party has opened its markets to such a degree as to be no longer classified as a true Marxist party. A sort of tacit consent, and a desire in China's case to escape the chaos of pre-1949 memory, probably plays a role.

In 1991 the Soviet Union was dismantled and the new Russian state, alongside the other emerging republics, ceased to identify themselves with Marxism. Other nations around the world followed suit. Since then, radical Marxism or Communism has generally ceased to be a prominent political force in global politics, and has largely been replaced by more moderate versions of democratic socialism—or, more commonly, by neoliberal capitalism. Marxism has also had to engage with the rise in the Environmental movement. Theorists including Joel Kovel and Michael Löwy have synthesized Marxism, socialism, ecology and environmentalism into an ideology known as Eco-socialism.

The modern social democratic current came into being through a break within the socialist movement in the early 20th century, between two groups holding different views on the ideas of Karl Marx. Many related movements, including pacifism, anarchism, and syndicalism, arose at the same time (often by splitting from the main socialist movement, but also through the emergence of new theories) and had various, quite different objections to Marxism. The social democrats, who were the majority of socialists at this time, did not reject Marxism (and in fact claimed to uphold it), but wanted to reform it in certain ways and tone down their criticism of capitalism. They argued that socialism should be achieved through evolution rather than revolution. Such views were strongly opposed by the revolutionary socialists, who argued that any attempt to reform capitalism was doomed to fail, because the reformists would be gradually corrupted and eventually turn into capitalists themselves.

Despite their differences, the reformist and revolutionary branches of socialism remained united until the outbreak of World War I. The war proved to be the final straw that pushed the tensions between them to breaking point. The reformist socialists supported their respective national governments in the war, a fact that was seen by the revolutionary socialists as outright treason against the working class (Since it betrayed the principle that the workers "have no nation", and the fact that usually the lowest classes are the ones sent into the war to fight, and die, putting the cause at the side). Bitter arguments ensued within socialist parties, as for example between Eduard Bernstein (reformist socialist) and Rosa Luxemburg (revolutionary socialist) within the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Eventually, after the Russian Revolution of 1917, most of the world's socialist parties fractured. The reformist socialists kept the name "Social democrats", while the revolutionary socialists began calling themselves "Communists", and soon formed the modern Communist movement. (See also Comintern)

Since the 1920s, doctrinal differences have been constantly growing between social democrats and Communists (who themselves are not unified on the way to achieve socialism), and Social Democracy is mostly used as a specifically Central European label for Labour Parties since then, especially in Germany and the Netherlands and especially since the 1959 Godesberg Program of the German SPD that rejected the praxis of class struggle altogether.

The term "socialism" could be used to describe two fundamentally different ideologies - democratic socialism and Marxist-Leninist socialism. While Marxist-Leninists (Trotskyists, Stalinists, and Maoists) are often described as communists in the contemporary media, they are not recognized as such academically or by themselves. The Marxist-Leninists sought to work towards the workers' utopia in Marxist ideology by first creating a socialist state, which historically had almost always been a single-party dictatorship. On the other hand, democratic socialists attempt to work towards an ideal state by social reform and are often little different from social democrats, with the democratic socialists having a more leftist stance.

The Marxist-Leninist form of government has been in decline since the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite states. Very few countries have governments which describe themselves as socialist. As of 2007, Laos, Vietnam, Nepal, Cuba, and the People's Republic of China had governments in power which describe themselves as socialist in the Marxist sense.

On the contrary, electoral parties which describe themselves as socialist or democratic socialist are on the rise, joined together by international organizations such as the Socialist International and the Fourth International. Parties described as socialist are currently dominant in Third World democracies and serve as the ruling party or the main opposition party in most European democracies. Eco-socialism, and Green politics with a strong leftist tinge, are on the rise in European democracies.

The characterization of a party or government often has little to do with its actual economical and social platform. The government of mainland China, which describes itself as socialist, allows a large private sector to flourish and is socially conservative compared to most Western democracies. A more specific example is universal health-care, which is a trademark issue of many European socialist parties but does not exist in mainland China. Therefore, the historical and cultural aspects of a movement must be taken into context in order for one to arrive at an accurate conclusion of its political ideology from its nominal characterization.

A number of states declared an allegiance to the principles of Marxism and have been ruled by self-described Communist Parties, either as a single-party state or a single list, which includes formally several parties, as was the case in the German Democratic Republic. Due to the dominance of the Communist Party in their governments, these states are often called "communist states" by Western political scientists. However, they have described themselves as "socialist", reserving the term "communism" for a future classless society, in which the state would no longer be necessary (on this understanding of communism, "communist state" would be an oxymoron) for instance, the USSR was the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Marxists contend that, historically, there has never been any communist country.

Communist governments have historically been characterized by state ownership of productive resources in a planned economy and sweeping campaigns of economic restructuring such as nationalization of industry and land reform (often focusing on collective farming or state farms.) While they promote collective ownership of the means of production, Communist governments have been characterized by a strong state apparatus in which decisions are made by the ruling Communist Party. Dissident 'authentic' communists have characterized the Soviet model as state socialism or state capitalism.

Marxism-Leninism, strictly speaking, refers to the version of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin known as Leninism. However, in various contexts, different (and sometimes opposing) political groups have used the term "Marxism-Leninism" to describe the ideologies that they claimed to be upholding. The core ideological features of Marxism-Leninism are those of Marxism and Leninism, that is to say, belief in the necessity of a violent overthrow of capitalism through communist revolution, to be followed by a dictatorship of the proletariat as the first stage of moving towards communism, and the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat in this effort. Those who view themselves as Marxist-Leninists, however, vary with regards to the leaders and thinkers that they choose to uphold as progressive (and to what extent). Maoists tend to downplay the importance of all other thinkers in favour of Mao Zedong, whereas Hoxhaists repudiate Mao.

Leninism holds that capitalism can only be overthrown by revolutionary means; that is, any attempts to reform capitalism from within, such as Fabianism and non-revolutionary forms of democratic socialism, are doomed to fail. The first goal of a Leninist party is to educate the proletariat, so as to remove the various modes of false consciousness the bourgeois have instilled in them, instilled in order to make them more docile and easier to exploit economically, such as religion and nationalism. Once the proletariat has gained class consciousness the party will coordinate the proletariat's total might to overthrow the existing government, thus the proletariat will seize all political and economic power. Lastly the proletariat (thanks to their education by the party) will implement a dictatorship of the proletariat which would bring upon them socialism, the lower phase of communism. After this, the party would essentially dissolve as the entire proletariat is elevated to the level of revolutionaries.

The dictatorship of the proletariat refers to the absolute power of the working class. It is governed by a system of proletarian direct democracy, in which workers hold political power through local councils known as soviets.

Trotsky advocated proletarian revolution as set out in his theory of "permanent revolution", and he argued that in countries where the bourgeois-democratic revolution had not triumphed already (in other words, in places that had not yet implemented a capitalist democracy, such as Russia before 1917), it was necessary that the proletariat make it permanent by carrying out the tasks of the social revolution (the "socialist" or "communist" revolution) at the same time, in an uninterrupted process. Trotsky believed that a new socialist state would not be able to hold out against the pressures of a hostile capitalist world unless socialist revolutions quickly took hold in other countries as well, especially in the industrial powers with a developed proletariat.

On the political spectrum of Marxism, Trotskyists are considered to be on the left. They fervently support democracy, oppose political deals with the imperialist powers, and advocate a spreading of the revolution until it becomes global.

Trotsky developed the theory that the Russian workers' state had become a "bureaucratically degenerated workers' state". Capitalist rule had not been restored, and nationalized industry and economic planning, instituted under Lenin, were still in effect. However, the state was controlled by a bureaucratic caste with interests hostile to those of the working class. Trotsky defended the Soviet Union against attack from imperialist powers and against internal counter-revolution, but called for a political revolution within the USSR to restore socialist democracy. He argued that if the working class did not take power away from the Stalinist bureaucracy, the bureaucracy would restore capitalism in order to enrich itself. In the view of many Trotskyists, this is exactly what has happened since the beginning of Glasnost and Perestroika in the USSR. Some argue that the adoption of market socialism by the People's Republic of China has also led to capitalist counter-revolution.

The term "Mao Zedong Thought" has always been the preferred term by the Communist Party of China, and the word "Maoism" has never been used in its English-language publications except pejoratively. Likewise, Maoist groups outside China have usually called themselves Marxist-Leninist rather than Maoist, a reflection of Mao's view that he did not change, but only developed, Marxism-Leninism. However, some Maoist groups believing Mao's theories to have been sufficiently substantial additions to the basics of the Marxist , call themselves "Marxist-Leninist-Maoist" (MLM) or simply "Maoist".

In the People's Republic of China, Mao Zedong Thought is part of the official doctrine of the Communist Party of China, but since the 1978 beginning of Deng Xiaoping's market economy-oriented reforms, the concept of "socialism with Chinese characteristics" has come to the forefront of Chinese politics, Chinese economic reform has taken hold, and the official definition and role of Mao's original ideology in the PRC has been radically altered and reduced (see History of China).

Unlike the earlier forms of Marxism-Leninism in which the urban proletariat was seen as the main source of revolution, and the countryside was largely ignored, Mao believed that peasantry could be the main force behind a revolution, led by the proletariat and a vanguard Communist party. The model for this was of course the Chinese communist rural Protracted People's War of the 1920s and 1930s, which eventually brought the Communist Party of China to power. Furthermore, unlike other forms of Marxism-Leninism in which large-scale industrial development was seen as a positive force, Maoism made all-round rural development the priority.

Mao felt that this strategy made sense during the early stages of socialism in a country in which most of the people were peasants. Unlike most other political ideologies, including other socialist and Marxist ones, Maoism contains an integral military doctrine and explicitly connects its political ideology with military strategy. In Maoist thought, "political power grows from the barrel of the gun" (a famous quote by Mao), and the peasantry can be mobilized to undertake a "people's war" of armed struggle involving guerrilla warfare in three stages.

Two major traditions can be observed within Left communism: the Dutch-German tradition; and the Italian tradition. The political positions those traditions have in common are a shared opposition to what is termed frontism, nationalism, all kinds of national liberation movements and parliamentarianism and there is an underlying commonality at a level of abstract theory. Crucially, Left Communist groups from both traditions tend to identify elements of commonality in each other.

The historical origins of Left Communism can be traced to the period before the First World War, but it only came into focus after 1918 . All Left Communists were supportive of the October Revolution in Russia, but retained a critical view of its development. Some, however, would in later years come to reject the idea that the revolution had a proletarian or socialist nature, asserting that it had simply carried out the tasks of the bourgeois revolution by creating a state capitalist system.

Left Communism first came into being as a clear movement in or around 1918. Its essential features were: a stress on the need to build a Communist Party entirely separate from the reformist and centrist elements who were seen as having betrayed socialism in 1914, opposition to all but the most restricted participation in elections, and an emphasis on the need for revolutionaries to move on the offensive. Apart from that, there was little in common between the various wings. Only the Italians accepted the need for electoral work at all for a very short period of time, and the German-Dutch, Italian and Russian wings opposed the "right of nations to self-determination", which they denounced as a form of bourgeois nationalism.

Marx defined "communism" as a classless, egalitarian and stateless society. To Marx, the notion of a communist state would have seemed an oxymoron, as he defined communism as the phase reached when class society and the state had already been abolished. Once the lower stage towards communism, commonly referred to as socialism, had been established, society would develop new social relations over the course of several generations, reaching what Marx called the higher phase of communism when not only bourgeois relations but every class social relations had been abandoned. Such a development has yet to occur in any historical self-claimed socialist state. Marxism-Leninism is a term originally coined by the CPSU in order to denote the ideology that Vladimir Lenin had built upon the thought of Karl Marx. There are two broad areas that have set apart Marxism-Leninism as a school of thought.

First, Lenin's followers generally view his additions to the body of Marxism as the practical corollary to Marx's original theoretical contributions of the 19th century; insofar as they apply under the conditions of advanced capitalism that they found themselves working in. Lenin called this time-frame the era of Imperialism. For example, Joseph Stalin wrote that The most important consequence of a Leninist-style theory of Imperialism is the strategic need for workers in the industrialized countries to bloc or ally with the oppressed nations contained within their respective countries' colonies abroad in order to overthrow capitalism. This is the source of the slogan, which shows the Leninist conception that not only the proletariat, as is traditional to Marxism, are the sole revolutionary force, but all oppressed people:

Second, the other distinguishing characteristic of Marxism-Leninism is how it approaches the question of organization. Lenin believed that the traditional model of the Social Democratic parties of the time, which was a loose, multitendency organization was inadequate for overthrowing the Tsarist regime in Russia. He proposed a cadre of professional revolutionaries that disciplined itself under the model of Democratic Centralism.

Trotskyism is the usual term for followers of the ideas of Russian Marxist Leon Trotsky, the second most prominent leader of the Russian Revolution. Trotsky was a contemporary of Lenin from the early years of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, where he led a small trend in competition with both Lenin's Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks; nevertheless Trotsky's followers claim to be the heirs of Lenin in the same way that mainstream Marxist-Leninists do. There are several distinguishing characteristics of this school of thought; foremost is the theory of Permanent Revolution. Another shared characteristic between Trotskyists is a variety of theoretical justifications for their negative appraisal of the post-Lenin Soviet Union; that is to say, after Trotsky was expelled by a majority vote from the CPSU and subsequently from the Soviet Union. Trotsky characterized the government of the USSR after his expulsion as being dominated by a "bureaucratic caste" and called for it to be overthrown. Trotskists as a consequence usually advocate the overthrow of socialist governments around the world that are ruled by Marxist-Leninist parties.

Left communism is the range of communist viewpoints held by the communist left, which criticizes the political ideas of the Bolsheviks from a position that is asserted to be more authentically Marxist and proletarian than the views of Leninism held by the Communist International after its first two congresses.

Although she lived before left communism became a distinct tendency, Rosa Luxemburg has been heavily influential for most left communists, both politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Herman Gorter, Anton Pannekoek, Otto Rühle, Karl Korsch, Amadeo Bordiga, and Paul Mattick.

Prominent left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Current and the International Bureau for the Revolutionary Party. Also, different factions from the old Bordigist International Communist Party are considered left communist organizations.

Structural Marxism is an approach to Marxism based on structuralism, primarily associated with the work of the French theorist Louis Althusser and his students. It was influential in France during the late 1960s and 1970s, and also came to influence philosophers, political theorists and sociologists outside of France during the 1970s.

Autonomism is a term applied to a variety of social movements around the world, which emphasizes the ability to organize in autonomous and horizontal networks, as opposed to hierarchical structures such as unions or parties. Autonomist Marxists, including Harry Cleaver, broaden the definition of the working-class to include salaried and unpaid labour, such as skilled professions and housework; it focuses on the working class in advanced capitalist states as the primary force of change in the construct of capital. Modern autonomist theorists such as Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt argue that network power constructs are the most effective methods of organization against the neoliberal regime of accumulation, and predict a massive shift in the dynamics of capital into a 21st Century Empire.

Marxist humanism is a branch of Marxism that primarily focuses on Marx's earlier writings, especially the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 in which Marx develops his theory of alienation, as opposed to his later works, which are considered to be concerned more with his structural conception of capitalist society. It was opposed by Louis Althusser's "antihumanism", who qualified it as a revisionist movement.

Marxist humanists contend that ‘Marxism’ developed lopsidedly because Marx’s early works were unknown until after the orthodox ideas were in vogue the Manuscripts of 1844 were published only in 1932 and it is necessary to understand Marx’s philosophical foundations to understand his latter works properly.

Criticisms of Marxism have come from the political left as well as the political right. Democratic socialists and social democrats reject the idea that socialism can be accomplished only through class conflict and a proletarian revolution. Many anarchists reject the need for a transitory state phase. Some thinkers have rejected the fundamentals of Marxist theory, such as historical materialism and the labour theory of value.

Some of the primary criticisms of socialism and by extension Marxism are distorted or absent price signals, slow or stagnant technological advance, reduced incentives, reduced prosperity, feasibility,

;Footnotes

;Bibliography |year= 1967 [1913]|publisher= Foreign Languages Press |location= Peking |isbn=|nopp=|ref=Len67}} Available online at here |year= 1849 |publisher=Neue Rheinische Zeitung |location=Germany |isbn=|nopp=|ref=Mar49}} Available online here

}} Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Category:Economic ideologies Category:Criticism of religion Category:Philosophical movements Category:Philosophical traditions Category:Theories of history Category:Karl Marx Category:Sociological paradigms Category:Communism Category:Socialism Category:Social theories Category:Materialism

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.