- Order:

- Duration: 2:09

- Published: 11 Mar 2009

- Uploaded: 10 May 2011

- Author: AtonalBrainHarvest

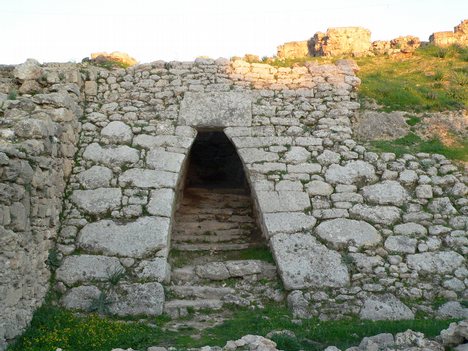

Most excavations of Ugarit were undertaken by archaeologist Claude Schaeffer from the Prehistoric and Gallo-Roman Museum in Strasbourg. The excavations uncovered a royal palace of 90 rooms laid out around eight enclosed courtyards, many ambitious private dwellings. Crowning the hill where the city was built were two main temples: one to Baal the "king", son of El, and one to Dagon, the chthonic god of fertility and wheat.

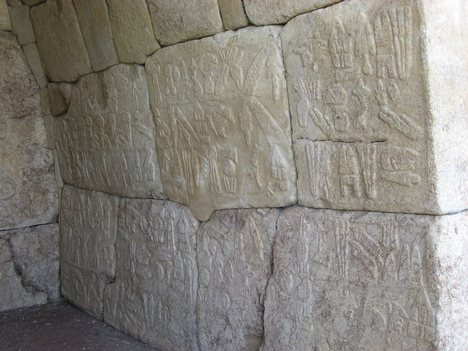

On excavation of the site, several deposits of cuneiform clay tablets were found; all dating from the last phase of Ugarit, around 1200 BC. These represented a palace library, a temple library and—apparently unique in the world at the time—two private libraries, one belonging to a diplomat named Rapanu) that contained diplomatic, legal, economic, administrative, scholastic, literary and religious texts. The tablets are written in Sumerian, Hurrian, Akkadian (the language of diplomacy at this time in the ancient Near East), or Ugaritic (a previously unknown language). No less than seven different scripts were in use at Ugarit: Egyptian and Luwian hieroglyphs, and Cypro-Minoan, Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian, and Ugaritic cuneiform.

During excavations in 1958, yet another library of tablets was uncovered. These were, however, sold on the black market and not immediately recovered. The "Claremont Ras Shamra Tablets" are now housed at the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, Claremont School of Theology, Claremont, California. They were edited by Loren R. Fisher in 1971. In 1973, an archive containing around 120 tablets was discovered during rescue excavations; in 1994 more than 300 further tablets were discovered on this site in a large ashlar building, covering the final years of the Bronze Age city's existence.

The most important piece of literature recovered from Ugarit is arguably the Baal cycle, describing the basis for the religion and cult of the Canaanite Baal.

The first written evidence mentioning the city comes from the nearby city of Ebla, ca. 1800 BC. Ugarit passed into the sphere of influence of Egypt, which deeply influenced its art. The earliest Ugaritic contact with Egypt (and the first exact dating of Ugaritic civilization) comes from a carnelian bead identified with the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret I, 1971 BC–1926 BC. A stela and a statuette from the Egyptian pharaohs Senusret III and Amenemhet III have also been found. However, it is unclear at what time these monuments got to Ugarit. Amarna letters from Ugarit ca. 1350 BC records one letter each from Ammittamru I, Niqmaddu II, and his queen. , Mycaenean ceramic imported to Ugarit, 14th-13th century BC (Louvre)]] From the 16th to the 13th century BC Ugarit remained in constant touch with Egypt and Cyprus (named Alashiya).

The last Bronze Age king of Ugarit, Ammurapi, was a contemporary of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma II. The exact dates of his reign are unknown. However, a letter by the king is preserved. Ammurapi stresses the seriousness of the crisis faced by many Near Eastern states from invasion by the advancing Sea Peoples in a dramatic response to a plea for assistance from the king of Alasiya. Ammurapi highlights the desperate situation Ugarit faced in letter RS 18.147:

My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka?...Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.

Unfortunately for Ugarit, no help arrived and Ugarit was burned to the ground at the end of the Bronze Age. Its destruction levels contained Late Helladic IIIB ware, but no LH IIIC (see Mycenaean period). Therefore, the date of the destruction is important for the dating of the LH IIIC phase. Since an Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah was found in the destruction levels, 1190 BC was taken as the date for the beginning of the LH IIIC. A cuneiform tablet found in 1986 shows that Ugarit was destroyed after the death of Merneptah. It is generally agreed that Ugarit had already been destroyed by the 8th year of Kate III—i. e. 1178 BC.

Whether Ugarit was destroyed before or after Hattusa, the Hittite capital, is debated. The destruction is followed by a settlement hiatus. Many other Mediterranean cultures were deeply disordered just at the same time, apparently by invasions of the mysterious "Sea Peoples."

The discovery of the Ugaritic archives has been of great significance to biblical scholarship, as these archives for the first time provided a detailed description of Canaanite religious beliefs during the period directly preceding the Israelite settlement. These texts show significant parallels to Biblical Hebrew literature, particularly in the areas of divine imagery and poetic form. Ugaritic poetry has many elements later found in Hebrew poetry: parallelisms, meters, and rhythms. The discoveries at Ugarit have led to a new appraisal of the Old Testament as literature.

In the north-east quarter of the walled enclosure the remains of three significant buildings were unearthed; the temples of Baal and Dagon and the library (sometimes referred to as the high priest's house). Within these structures atop the acropolis numerous invaluable mythological texts were found. Since the 1930s these texts have opened some initial understanding of the Canaanite mythological world. The Baal cycle represents Baal's destruction of Yam (the chaos sea monster), demonstrating the relationship of Canaanite chaoskampf with those of Mesopotamia and the Aegean: a warrior god rises up as the hero of the new pantheon to defeat chaos and bring order.

It is almost certain that the cult(s) of Baal in the Levant influenced later Israelite cult and mythology. Yahweh often takes on the chaoskampf role of Baal in his struggle with the chaotic sea. It would, however, be incorrect to use later redacted biblical texts to reconstruct Canaanite religion or cult.

While El is the chief of the Canaanite pantheon, very little attention is paid to him in the cultic/mythological texts. This is rather common of Middle to Late Bronze Age mythology; the high god is drawn into the background whilst new warrior deities move to centre stage. In Ugarit and much of the Levant this figure is Baal; to the Shasu / Shosu this is Yahweh and his consort, and in Mesopotamia this is Marduk. These warrior-god mythologies show remarkable points of contact and are most likely reflections of the same archetypal myth.

Category:Archaeological sites in Syria Category:History of Syria Category:Amarna letters locations Category:Cultural Sites on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List Category:Former populated places in Syria Category:Latakia Governorate

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Malek Jandaliمالك جندلي |

|---|---|

| Background | solo_singer |

| Birth name | |

| Origin | Homs, Syria |

| Born | December 25, 1972Waldbröl, Germany |

| Instrument | Piano |

| Genre | ClassicalJazzArabic ClassicalFilm Music |

| Occupation | Composer-Pianist |

| Years active | 1981–present |

| Label | Soul b Music |

| Url | www.malekjandali.com/ |

| Notable instruments | Steinway & Sons |

Malek Jandali () (b. 1972), is a Syrian composer and pianist considered to be among the most versatile and creative musicians in the Arab world. He is the first Syrian and only Arab musician to arrange music based on the oldest music notation in the world, which was discovered in the Bronze City of Ugarit, Syria.

Malek has a special interest in Arabic music where he incorporates the "maqams" or modes with western harmony in his piano and orchestral compositions. His constantly expanding horizons have led him to become a unique composer with the ability to juxtapose oriental melodies with complex harmony to end up with an original blend of civilizations.

He also experiments not only with live, acoustical instruments, but also the implementation of MIDI and electronic sounds. A prolific composer, Malek has written and produced music for corporate multimedia, video presentations and commercials. Recent projects include scoring music for an independent films, television programs and documentaries.

The earliest music notation of which a written record exists anywhere on earth appears to be the Hurrian Hymn (Fink 1988; Dumbrill 2000,[page needed]). The clay tablets were discovered in the ancient city of Ugarit on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. This music may have been microtonal, even though, while interpretation of many aspects of the Hurrian records has been disputed (West 1994), expert opinion overwhelmingly favors some variety of diatonic, Pythagorean tuning (Duchesne-Guillemin 1975, 1977, 1980, 1984; Kilmer 1965, 1971, 1974, 1976; Vitale 1982; West 1994; Wulstan 1968).

Category:1972 births Category:Living people Category:Experimental musicians Category:Sound artists Category:21st-century classical composers Category:Syrian musicologists Category:Syrian composers Category:Syrian pianists Category:People from Homs Category:Video game composers Category:Arab musicians Category:American composers Category:Syrian classical pianists Category:American pianists

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūbi |

|---|---|

| Title | Sultan of Egypt and Syria |

| Caption | Statue of Saladin in Damascus. |

| Reign | 1174–1193 |

| Coronation | 1174, Cairo |

| Religion | Muslim |

| Full name | Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūbi |

| Predecessor | Nur ad-Din Zangi |

| Successor | Al-Afdal (Syria) Al-Aziz Uthman (Egypt) |

| Dynasty | Ayyubid |

| Father | Najm ad-Dīn Ayyūb |

| Date of birth | c. 1137–1138 |

| Place of birth | Tikrit, Iraq |

| Date of death | March 4, 1193 CE (aged 55–56) |

| Place of death | Damascus, Syria |

| Place of burial | Umayyad Mosque, Damascus, Syria |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

He led the Muslims against the Crusaders and eventually recaptured Palestine from the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem after his victory in the Battle of Hattin. As such, he is a notable figure in Kurdish, Arab, and Muslim culture. Saladin was a strict adherent of Sunni Islam and a mystical disciple of the Qadiri Sufi order. His chivalrous behavior was noted by Christian chroniclers, especially in the accounts of the siege of Kerak in Moab, and despite being the nemesis of the Crusaders he won the respect of many of them, including Richard the Lionheart; rather than becoming a hated figure in Europe, he became a celebrated example of the principles of chivalry.

Saladin, who now lived in Damascus, was reported to have a particular fondness of the city, but information on his early childhood is scarce. About education, Saladin wrote "children are brought up in the way in which their elders were brought up." According to one of his biographers, al-Wahrani, Saladin was able to answer questions on Euclid, the Almagest, arithmetic, and law, but this was an academic ideal and it was study of the Qur'an and the "sciences of religion" that linked him to his contemporaries. Another factor which may have affected his interest in religion was that during the First Crusade, Jerusalem was taken in a surprise attack by the Christians. After Shawar was successfully reinstated as vizier, he demanded that Shirkuh withdraw his army from Egypt for a sum of 30,000 dinars, but he refused insisting it was Nur ad-Din's will that he remain. Saladin's role in this expedition was minor, and it is known that he was ordered by Shirkuh to collect stores from Bilbais prior to its siege by a combined force of Crusaders and Shawar's troops.

hurling the heads of slain Muslims over ramparts during a siege]]

After the sacking of Bilbais, the Crusader-Egyptian force and Shirkuh's army were to engage in a battle on the desert border of the Nile River, just west of Giza. Saladin played a major role, commanding the right wing of the Zengid army, while a force of Kurds commanded the left, and Shirkuh stationed in the center. Muslim sources at the time, however, put Saladin in the "baggage of the center" with orders to lure the enemy into a trap by staging a false retreat. The Crusader force enjoyed early success against Shirkuh's troops, but the terrain was too steep and sandy for their horses, and commander Hugh of Caesarea was captured while attacking Saladin's unit. After scattered fighting in little valleys to the south of the main position, the Zengid central force returned to the offensive; Saladin joined in from the rear.

The battle ended in a Zengid victory, and Saladin is credited to have helped Shirkuh in one of the "most remarkable victories in recorded history", according to Ibn al-Athir, although more of Shirkuh's men were killed and the battle is considered by most sources as not a total victory. Saladin and Shirkuh moved towards Alexandria where they were welcomed, given money, arms, and provided a base. Faced by a superior Crusader-Egyptian force who attempted to besiege the city, Shirkuh split his army. He and the bulk of his force withdrew from Alexandria, while Saladin was left with the task of guarding the city.

Shirkuh engaged in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and Amalric I of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, in which Shawar requested Amalric's assistance. In 1169, Shawar was reportedly assassinated by Saladin, and Shirkuh died later that year. Nur ad-Din chose a successor for Shirkuh, but al-Adid appointed Saladin to replace Shawar as vizier.

The reasoning behind the Shia al-Adid's selection of Saladin, a Sunni, varies. Ibn al-Athir claims that the caliph chose him after being told by his advisers that "there is no one weaker or younger" than Saladin, and "not one of the emirs obeyed him or served him." However, according to this version, after some bargaining, he was eventually accepted by the majority of emirs. Al-Adid's advisers were also suspected of attempting to split the Syria-based Zengid ranks. Al-Wahrani wrote that Saladin was selected because of the reputation of his family in their "generosity and military prowess." Imad ad-Din wrote that after the brief mourning period of Shirkuh, during which "opinions differed", the Zengid emirs decided upon Saladin and forced the caliph to "invest him as vizier." Although positions were complicated by rival Muslim leaders, the bulk of the Syrian rulers supported Saladin due to his role in the Egyptian expedition, in which he gained a record of impeccable military qualifications.

Inaugurated as vizier on March 26, Saladin repented "wine-drinking and turned from frivolity to assume the dress of religion." Having gained more power and independence than ever before in his career, he still faced the issue of ultimate loyalty between al-Adid and Nur ad-Din. The latter was rumored to be clandestinely hostile towards Saladin's appointment and was quoted as saying, "how dare he [Saladin] do anything without my orders?" He wrote several letters to Saladin, who dismissed them without abandoning his allegiance to Nur ad-Din.

Later in the year, a group of Egyptian soldiers and emirs attempted to assassinate Saladin, but having already known of their intentions, he had the chief conspirator, Mu'tamin al-Khilafa—the civilian controller of the Fatimid Palace—killed. The day after, 50,000 black African soldiers from the regiments of the Fatimid army opposed to Saladin's rule along with a number of Egyptian emirs and commoners staged a revolt. By August 23, Saladin had decisively quelled the uprising, and never again had to face a military challenge from Cairo.

Towards the end of 1169, Saladin—with reinforcements from Nur ad-Din—defeated a massive Crusader-Byzantine force near Damietta. Afterward, in the spring of 1170, Nur ad-Din sent Saladin's father to Egypt in compliance with Saladin's request, as well as encouragement from the Baghdad-based Abbasid caliph, al-Mustanjid, who aimed to pressure Saladin in deposing his rival caliph, al-Adid. Saladin himself had been strengthening his hold on Egypt and widening his support base there. He began granting his family members high-ranking positions in the region and increased Sunni influence in Cairo; he ordered the construction of a college for the Maliki branch of Sunni Islam in the city, as well as one for the Shafi'i denomination to which he belonged in al-Fustat.

After establishing himself in Egypt, Saladin launched a campaign against the Crusaders, besieging Darum in 1170. Amalric withdrew his Templar garrison from Gaza to assist him in defending Darum, but Saladin evaded their force and fell on Gaza instead. He destroyed the town built outside the city's castle and killed most of its inhabitants after they were refused entry into the castle. It is unclear exactly when, but during that same year, he attacked and captured the Crusader castle of Eilat, built on an island off the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. It did not pose a threat to the passage of the Muslim navy, but could harass smaller parties of Muslim ships and Saladin decided to clear it from his path. He died on September 13 and five days later, the Abbasid khutba was pronounced in Cairo and al-Fustat, proclaiming al-Mustadi as caliph.

On September 25, Saladin left Cairo to take part in a joint attack on Kerak and Montreal, the desert castles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, with Nur ad-Din who would attack from Syria. Prior to arriving at Montreal, Saladin withdrew, realizing that if he met Nur ad-Din at Shaubak, he would be refused return to Egypt because of Nur ad-Din's reluctance to consolidate such massive territorial control to Saladin. Also, there was a chance that the Crusader kingdom—which acted as a buffer state between Syria and Egypt—could have collapsed had the two leaders attacked it from the east and the coast. This would have given Nur ad-Din the opportunity to annex Egypt. Saladin claimed he withdrew amid Fatimid plots against him, but Nur ad-Din did not accept "the excuse."

On July 31, 1173, Saladin's father Ayyub was wounded in a horse-riding accident, ultimately causing his death on August 9. In 1174, Saladin sent Turan-Shah to conquer Yemen to allocate it and its port Aden to the territories of the Ayyubid Dynasty. Yemen also served as an emergency territory, to which Saladin could flee in the event of an invasion by Nur ad-Din.

In the wake of Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin faced a difficult decision; he could move his army against the Crusaders from Egypt or wait until invited by as-Salih in Syria to come to his aid and launch a war from there. He could also take it upon himself to annex Syria before it could possibly fall into the hands of a rival, but feared that attacking a land that formerly belonged to his master—which is forbidden in the Islamic principles he followed—could portray him as hypocritical and thus, unsuitable for leading the war against the Crusaders. Saladin saw that in order to acquire Syria, he either needed an invitation from as-Salih or warn him that potential anarchy and danger from the Crusaders could rise.

When as-Salih was removed to Aleppo in August, Gumushtigin, the emir of the city and a captain of Nur ad-Din's veterans assumed guardianship over him. The emir prepared to unseat all of his rivals in Syria and al-Jazira, beginning with Damascus. In this emergency, the emir of Damascus appealed to Saif al-Din (a cousin of Gumushtigin) of Mosul for assistance against Aleppo, but he refused, forcing the Syrians to request the aid of Saladin who complied. Saladin rode across the desert with 700 picked horsemen, passing through al-Kerak then reaching Bosra and according to him, was joined by "emirs, soldiers, Kurds, and Bedouins—the emotions of their hearts to be seen on their faces." On November 23, he arrived in Damascus amid general acclamations and rested at his father's old home there, until the gates of the Citadel of Damascus were opened to him four days later. He installed himself in the castle and received the homage and salutations of the citizens. Then he moved north towards Aleppo, besieging it on December 30 after Gumushtigin refused to abdicate his throne. As-Salih, afraid of Saladin, came out of his palace and appealed to the inhabitants not to surrender him and the city to the invading force. One of Saladin's chroniclers claimed "the people came under his spell."

Gumushtigin requested from Rashid ad-Din Sinan, grand-master of the Assassins who were already at odds with Saladin since he replaced the Fatimids of Egypt, to assassinate Saladin in his camp. A group of thirteen Assassins easily gained admission into Saladin's camp, but were detected immediately before they carried out their attack. One was killed by a general of Saladin and the others were slain while trying to escape. To make the situation more difficult for him, Raymond of Tripoli gathered his forces by Nahr al-Kabir where he was well-placed for an attack on Muslim territory. He later moved toward Homs, but retreated after being told a relief force was being sent to the city by Saif al-Din. Soon after, Saladin entered Homs and captured its citadel in March 1175, after stubborn resistance from its defenders.

Saladin's successes alarmed Saif al-Din. As head of the descendants of Zengid, including Gumushtigin, he regarded Syria and Mesopotamia as his family estate and was angered when Saladin attempted to usurp their holdings. Saif al-Din mustered a large army and dispatched it to Aleppo whose defenders anxiously had awaited them. The combined forces of Mosul and Aleppo marched against Saladin in Hama. Heavily outnumbered, he initially attempted to make terms with the Zengids by abandoning all conquests north of the Damascus province, but they refused, insisting he return to Egypt. Seeing that a confrontation was unavoidable, Saladin prepared for battle, taking up a superior position on the hills by the gorge of the Orontes River. On April 13, 1175, the Zengid troops marched to attack his forces, but soon found themselves surrounded by Saladin's Ayyubid veterans who annihilated them. The battle ended in a decisive victory for Saladin who pursued the Zengid fugitives to the gates of Aleppo, forcing as-Salih's advisers to recognize his control of the provinces of Damascus, Homs, and Hama, as well as a number of towns outside Aleppo such as Ma'arat al-Numan.

After his victory against the Zengids, Saladin proclaimed himself king and suppressed the name of as-Salih in the Friday prayers and Islamic coinage. From then on, he ordered prayers in all the mosques of Syria and Egypt as the sovereign king and he issued at the Cairo mint gold coins bearing his name—al-Malik an-Nasir Yusuf Ayyub, ala ghaya "the King Strong to Aid, Joseph son of Job; exalted be the standard." The Abbasid caliph in Baghdad graciously welcomed Saladin's assumption of power and declared him "Sultan of Egypt and Syria."

The Battle of Hama did not end the contest for power between the Ayyubids and the Zengids, the final confrontation occurring in the spring of 1176. Saladin had brought up his forces from Egypt and Saif al-Din was levying troops among the minor states of Diyarbakir and al-Jazira. When Saladin crossed the Orontes, leaving Hama, the sun was eclipsed and despite viewing this as an omen, he continued his march north. He reached the Sultan's Mound, from Aleppo, where his forces encountered Saif al-Din's army. A hand-to-hand fight ensued and the Zengids managed to overthrow Saladin's left wing, driving it before him, when he himself charged at the head of the Zengid guard. The Zengid forces panicked and most of Saif al-Din's officers were killed or captured—he himself narrowly escaped. The Zengid army's camp, horses, baggage, tents, and stores were taken by the Ayyubids. The Zengid prisoners, however, were given gifts and freed by Saladin and all of the booty of his victory were handed to the army, not keeping a thing for himself.

He continued towards Aleppo which still closed its gates to him, halting before the city. On the way, his army took Buza'a, then captured Manbij. From there they headed west to besiege the fortress of A'zaz on May 15. A few days later, while Saladin was resting in one of his captain's tents, an assassin rushed forward at him and struck at his head with a knife. The cap of his head armor was not penetrated and he managed to grip the assassin's hand—the dagger only slashing his gambeson—and the assailant was soon killed. Saladin was unnerved at the attempt on his life, which he accused Gumushtugin and the Assassins of plotting, and so increased his efforts in the siege.

's Treatise Automata (1206 AD)]]

According to his version, one night, Saladin's guards noticed a spark glowing down the hill of Masyaf and then vanishing among the Ayyubid tents. Presently, Saladin awoke from his sleep to find a figure leaving the tent. He then saw that the lamps were displaced and beside his bed laid hot scones of the shape peculiar to the Assassins with a note at the top pinned by a poisoned dagger. The note threatened that he would be killed if he didn't withdraw from his assault. Saladin gave a loud cry, exclaiming that Sinan himself was the figure that left the tent. As such, Saladin told his guards to settle an agreement with Sinan.

Saladin remained in Cairo supervising its improvements, building colleges such as the Madrasa of the Sword Makers and ordering the internal administration of the country. In November 1177, he set out upon a raid into Palestine; the Crusaders had recently forayed into the territory of Damascus and so Saladin saw the truce was no longer worth preserving. The Christians sent a large portion of their army to besiege the fortress of Harim north of Aleppo and so southern Palestine bared few defenders.

Not discouraged by his defeat at Tell Jezer, Saladin was prepared to fight the Crusaders once again. In the spring of 1178, he was encamped under the walls of Homs and a few skirmishes occurred between his generals and the Crusader army. His forces in Hama won a victory over their enemy and brought the spoils, together with many prisoners of war to Saladin who ordered the captives to be beheaded for "plundering and laying waste the lands of the Faithful." He spent the rest of the year in Syria without a confrontation with his enemies.

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. As such, he ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire avoiding battle and lighting warning beacons on the hills on which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the Golan Heights. Baldwin advanced too rashly in pursuit of Farrukh-Shah's force which was concentrated southeast of Quneitra and was subsequently defeated by the Ayyubids. With this victory, Saladin decided to call in more troops from Egypt; he requested 1,500 horsemen to be sent by al-Adil.

In the summer of 1179, King Baldwin had set up an outpost on the road to Damascus and aimed to fortify a passage over the Jordan River, known as Jacob's Ford, that commanded the approach to the Banias plain (the plain was divided by the Muslims and the Christians). Saladin had offered 100,000 gold pieces for Baldwin to abandon the project which was peculiarly offensive to the Muslims, but to no avail. He then resolved to destroy the fortress, moving his headquarters to Banias. As the Crusaders hurried down to attack the Muslim forces, they fell into disorder, with the infantry falling behind. Despite early success, they pursued the Muslims far enough to become scattered and Saladin took advantage by rallying his troops and charged at the Crusaders. The engagement ended in a decisive Ayyubid victory and many high-ranking knights were captured. Saladin then moved to besiege the fortress which fell on August 30, 1179.

In the spring of 1180, while Saladin was in the area of Safad, anxious to commence a vigorous campaign against the Kingdom of Jerusalem, King Baldwin sent messengers to him with proposals of peace. Due to droughts and bad harvests hampering his commissariat, Saladin agreed to a truce. Raymond of Tripoli denounced the truce, but was compelled to accept after an Ayyubid raid in his territory in May and upon the appearance of Saladin's naval fleet off the port of Tartus.

After Nur al-Din and Saladin met at Geuk Su, the top Seljuk emir, Ikhtiyar al-Din al-Hasan, confirmed Arslan's submission, after which an agreement was drawn up. Saladin was enraged to receive a message from Arslan soon after, complaining of more abuses against his daughter. He threatened to attack the city of Malatya, saying, "it is two days march for me and I shall not dismount [my horse] until I am in the city."

In the summer of 1181, Saladin's former palace administrator Qara-Qush led a force to arrest Majd al-Din—a former deputy of Turan-Shah in the town of Zabid in Yemen—while he was entertaining Imad ad-Din at his estate in Cairo. Saladin's intimates accused him of misappropriating the revenues of Zabid, but Saladin himself replied there was no evidence against him. He realized the mistake and had Majd al-Din released in return for a payment of 80,000 dinars to him and other sums to Saladin's brothers al-Adil and Taj al-Muluk Bari. The controversial detainment of Majd al-Din was a part of the larger discontent associated with the aftermath of Turan-Shah's departure from Yemen; although his deputies continued to send him revenues from the province, centralized authority was lacking and internal quarrel arose between the Izz al-Din Uthman of Aden and Hittan of Zabid. Saladin wrote in a letter to al-Adil: "this Yemen is a treasure house ... We conquered it, but up to this day we have had no return and no advantage from it. There have been only innumerable expenses, the sending out of troops ... and expectations which did not produce what was hoped for in the end."

On May 11, 1182, Saladin along with half of the Egyptian Ayyubid army and numerous non-combatants left Cairo for Syria. On the evening before he departed, he sat with his companions and the tutor of one of his sons quoted a line of poetry: "enjoy the scent of the ox-eye plant of Najd, for after this evening it will come no more." Saladin took this as an evil omen and he never saw Egypt again. He arrived in Damascus in June to learn that Farrukh-Shah had attacked the Galilee, sacking Daburiyya and capturing Habis Jaldek, a fortress of great importance to the Crusaders. In July, Saladin dispatched Farrukh-Shah to attack Kawkab al-Hawa. Later, in August, the Ayyubids launched a naval and ground assault to capture Beirut; Saladin led his army in the Bekaa Valley. The assault was leaning towards failure and Saladin abandoned the operation to focus on issues in Mesopotamia.

Kukbary, the emir of Harran, invited Saladin to occupy the Jazira region, making up northern Mesopotamia. He complied and the truce between him and the Zengids officially ended in September 1182. Before he crossed the Euphrates, Saladin besieged Aleppo for three days, signaling that the truce was over.

Saladin proceeded to take Nusaybin which offered no resistance. A medium-sized town, Nusaybin was not of great importance, but it was located in a strategic position between Mardin and Mosul and within easy reach of Diyarbakir. In the midst of these victories, Saladin received word that the Crusaders were raiding the villages of Damascus. He replied "Let them... whilst they knock down villages, we are taking cities; when we come back, we shall have all the more strength to fight them." Meanwhile, in Aleppo, the emir of the city Zangi raided Saladin's cities to the north and east, such as Balis, Manbij, Saruj, Buza'a, al-Karzain. He also destroyed his own citadel at A'zaz to prevent it from being used by the Ayyubids if they were to conquer it.

Zangi did not offer long resistance. He was unpopular with his subjects and wished to return to his Sinjar, the city he governed previously. An exchange was negotiated where Zangi would hand over Aleppo to Saladin in return for the restoration of his control of Sinjar, Nusaybin, and ar-Raqqa. Zangi would hold these territories as Saladin's vassals on terms of military service. On June 12, Aleppo was formally placed in Ayyubid hands. The people of Aleppo had not known about these negotiations and were taken by surprise when Saladin's standard was hoisted over the citadel. Two emirs, including an old friend of Saladin, Izz al-Din Jurduk, welcomed and pledged their service to him. Saladin replaced the Hanafi courts with Shafi'i administration, despite a promise he would not interfere in the religious leadership of the city. Although he was short of money, Saladin also allowed the departing Zangi to take all the stores of the citadel that he could travel with and to sell the remainder—which Saladin purchased himself.

In spite of his earlier hesitation to go through with the exchange, he had no doubts about his success, stating that Aleppo was "the key to the lands" and "this city is the eye of Syria and the citadel is its pupil." For Saladin, the capture of the city marked the end of over eight years of waiting since he told Farrukh-Shah "we have only to do the milking and Aleppo will be ours." From his standpoint, he could now threaten the entire Crusader coast.

After spending one night in Aleppo's citadel, Saladin marched to Harim, near the Crusader-held Antioch. The city was held by Surhak, a "minor mamluk." Saladin offered him the city of Busra and property in Damascus in exchange for Harim, but when Surhak asked for more, his own garrison in Harim forced him out.

After several minor skirmishes and a stalemate in the siege that was initiated by the caliph, Saladin intended to find a way to withdraw from the siege without damage to his reputation while still keeping up some military pressure. He decided to attack Sinjar which was now held by Izz al-Din's brother Sharaf al-Din. It fell after a 15-day siege on December 30. Saladin's commanders and soldiers broke their discipline, plundering the city; Saladin only managed to protect the governor and his officers by sending them to Mosul. After establishing a garrison at Sinjar, he awaited a coalition assembled by Izz al-Din consisting of his forces, those from Aleppo, Mardin, and Armenia. Saladin and his army met the coalition at Harran in February 1183, but on hearing of his approach, the latter sent messengers to Saladin asking for peace. Each force returned to their cities and al-Fadil writes "They [Izz al-Din's coalition] advanced like men, like women they vanished."

On March 2, al-Adil from Egypt wrote to Saladin that the Crusaders had struck the "heart of Islam." Raynald de Châtillon had sent ships to from the Gulf of Aqaba to raid towns and villages off the coast of the Red Sea. It was not an attempt to extend the Crusader influence into that sea or to capture its trade routes, but merely a piratical move. Nonetheless, Imad al-Din writes the raid was alarming to the Muslims because they were not accustomed to attacks on that sea and Ibn al-Athir adds that the inhabitants had no experience with the Crusaders either as fighters or traders.

Ibn Jubair was told that sixteen Muslim ships were burnt by the Crusaders who then captured a pilgrim ship and caravan at Aidab. He also reported they intended to attack Medina and remove Muhammad's body. Al-Maqrizi added to the rumor by claiming Muhammad's tomb was going to be relocated Crusader territory so Muslims would make pilgrimages there. Fortunately for Saladin, al-Adil had his warships moved from Fustat and Alexandria to the Red Sea under the command of an Armenian mercenary Lu'lu. They broke the Crusader blockade, destroyed most of their ships, and pursued and captured those who anchored and fled into the desert. The surviving Crusaders, numbered at 170, were ordered to be killed by Saladin in various Muslim cities.

From Saladin's own point of view, in terms of territory, the war against Mosul was going well, but he still failed to achieve his objectives and his army was shrinking; Taqi al-Din took his men back to Hama, while Nasir al-Din Muhammad and his forces had left. This encouraged Izz al-Din and his allies to take the offensive. The previous coalition regrouped at Harzam some from Harran. In early April, without waiting for Nasir al-Din, Saladin and Taqi al-Din commenced their advance against the coalition, marching eastward to Ras al-Ein unhindered. By late April, after three days of "actual fighting" according to Saladin, the Ayyubids had captured Amid. He handed the city Nur al-Din Muhammad together with its stores—which consisted of 80,000 candles, a tower full of arrowheads, and 1,040,000 books. In return for a diploma granting him the city, Nur al-Din swore allegiance to Saladin, promising to follow him in every expedition in the war against the Crusaders and repairing damage done to the city. The fall of Amid, in addition to territory, convinced Il-Ghazi of Mardin to enter the service of Saladin, weakening Izz al-Din's coalition.

Saladin attempted to gain the Caliph an-Nasir's support against Izz al-Din by sending him a letter requesting a document that would give him legal justification for taking over Mosul and its territories. Saladin aimed to persuade the caliph claiming that while he conquered Egypt and Yemen under the flag of the Abbasids, the Zengids of Mosul openly supported the Seljuks (rivals of the caliphate) and only came to the caliph when in need. He also accused Izz al-Din's forces of disrupting the Muslim "Holy War" against the Crusaders, stating "they are not content not to fight, but they prevent those who can." Saladin defended his own conduct claiming that he had come to Syria to fight the Crusaders, end the heresy of the Assassins, and to end the wrong-doing of the Muslims. He also promised that if Mosul was given to him, it would lead to the capture of Jerusalem, Constantinople, Georgia, and the lands of the Almohads in the Maghreb, "until the word of God is supreme and the Abbasid caliphate has wiped the world clean, turning the churches into mosques." Saladin stressed that all this would happen by the will of God and instead of asking for financial or military support from the caliph, he would capture and give the caliph the territories of Tikrit, Daquq, Khuzestan, Kish Island, and Oman.

On September 29, Saladin crossed the Jordan River to attack Beisan which was found to be empty. The next day his forces sacked and burned the town and moved westwards. They intercepted Crusader reinforcements from Karak and Shaubak along the Nablus road and took a number of prisoners. Meanwhile, the main Crusader force under Guy of Lusignan moved from Sepphoris to al-Fula. Saladin sent out 500 skirmishers to harass their forces and he himself marched to Ain Jalut. When the Crusader force—reckoned to be the largest the kingdom ever produced from its own resources, but still outmatched by the Muslims—advanced, the Ayyubids unexpectedly moved down the stream of Ain Jalut. After a few Ayyubid raids—including attacks on Zir'in, Forbelet, and Mount Tabor—the Crusaders still were not tempted to attack their main force, and Saladin led his men back across the river once provisions and supplies ran low.

In July 1187 Saladin captured most of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. On July 4, 1187, at the Battle of Hattin, he faced the combined forces of Guy of Lusignan, King Consort of Jerusalem and Raymond III of Tripoli. In this battle alone the Crusader army was largely annihilated by the motivated army of Saladin. It was a major disaster for the Crusaders and a turning point in the history of the Crusades. Saladin captured Raynald de Châtillon and was personally responsible for his execution in retaliation for his attacking Muslim caravans. The members of these caravans had, in vain, besought his mercy by reciting the truce between the Muslims and the Crusaders, but he ignored this and insulted their prophet Muhammad before murdering and torturing a number of them. Upon hearing this, Saladin swore an oath to personally execute Raynald.

Guy of Lusignan was also captured. Seeing the execution of Raynald, he feared he would be next. But his life was spared by Saladin with the words, talking about Raynald:

Tyre, on the coast of modern-day Lebanon, was the last major Crusader city that was not captured by Muslim forces (strategically, it would have made more sense for Saladin to capture Tyre before Jerusalem—however, Saladin chose to pursue Jerusalem first because of the importance of the city to Islam). The city was now commanded by Conrad of Montferrat, who strengthened Tyre's defences and withstood two sieges by Saladin. In 1188, at Tortosa, Saladin released Guy of Lusignan and returned him to his wife, Queen Sibylla of Jerusalem. They went first to Tripoli, then to Antioch. In 1189, they sought to reclaim Tyre for their kingdom, but were refused admission by Conrad, who did not recognize Guy as king. Guy then set about besieging Acre.

The armies of Saladin engaged in combat with the army of King Richard at the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191, at which Saladin was defeated. All attempts made by Richard the Lionheart to re-take Jerusalem failed. However, Saladin's relationship with Richard was one of chivalrous mutual respect as well as military rivalry. When Richard became ill with fever, Saladin offered the services of his personal physician. Saladin also sent him fresh fruit with snow, to chill the drink, as treatment. At Arsuf, when Richard lost his horse, Saladin sent him two replacements. Richard suggested to Saladin that Palestine, Christian and Muslim, could be united through the marriage of his sister Joan of England, Queen of Sicily, to Saladin's brother, and that Jerusalem could be their wedding gift. However, the two men never met face to face and communication was either written or by messenger.

As leaders of their respective factions, the two men came to an agreement in the Treaty of Ramla in 1192, whereby Jerusalem would remain in Muslim hands but would be open to Christian pilgrimages. The treaty reduced the Latin Kingdom to a strip along the coast from Tyre to Jaffa. This treaty was supposed to last three years.

According to the some sources, British Commander General Edmund Allenby during World War I, proudly declared "today the wars of the Crusaders are completed " by rising up his sword towards statue of Saladin after capture of Damascus from Turkish troops. This quotation is incorrectly attributed to Allenby, as throughout his life he vehemently protested against his conquest of Palestine in 1917 being called a "Crusade". In 1933 Allenby reiterated this stance by saying: "The importance of Jerusalem lay in its strategic importance, there was no religious impulse in this campaign". As well British press celebrated his victory with cartoons of Richard the Lion-Hearted looking down at Jerusalem above the caption "At last my dream come true." After French General Henri Gouraud entered the city in July 1920 and kicking Saladin's tomb, Gouraud exclaimed, "Awake Saladin, we have returned. My presence here consecrates the victory of the Cross over the Crescent."

In 1898 German Emperor Wilhelm II visited Saladin's tomb to pay his respects. The visit, coupled with anti-colonial sentiments, led nationalist Arabs to reinvent the image of Saladin and portray him as a hero of the struggle against the West. The image of Saladin they used was the romantic one created by Walter Scott and other Europeans in the West at the time. It replaced Saladin's reputation as a figure who had been largely forgotten in the Muslim world, eclipsed by more successful figures such as Baybars of Egypt.

Modern Arab states have sought to commemorate Saladin through various measures, often based on the image created of him in the 19th century west. A governorate centered around Tikrit and Samarra in modern-day Iraq, Salah ad Din Governorate, is named after him, as is Salahaddin University in Arbil,the largest city of Iraqi Kurdistan. A suburb community of Arbil, Masif Salahaddin, is also named after him.

Few structures associated with Saladin survive within modern cities. Saladin first fortified the Citadel of Cairo (1175–1183), which had been a domed pleasure pavilion with a fine view in more peaceful times. In Syria, even the smallest city is centred on a defensible citadel, and Saladin introduced this essential feature to Egypt.

Among the forts he built was Qalaat al-Gindi, a mountaintop fortress and caravanserai in the Sinai. The fortress overlooks a large wadi which was the convergence of several caravan routes that linked Egypt and the Middle East. Inside the structure are a number of large vaulted rooms hewn out of rock, including the remains of shops and a water cistern. A notable archaeological site, it was investigated in 1909 by a French team under Jules Barthoux.

Although the Ayyubid dynasty that he founded would only outlive him by 57 years, the legacy of Saladin within the Arab World continues to this day. With the rise of Arab nationalism in the Twentieth Century, particularly with regard to the Arab-Israeli conflict, Saladin's heroism and leadership gained a new significance. Saladin's liberation of Palestine from the European Crusaders was put forth the inspiration for the modern-day Arabs' opposition to Zionism.

Moreover, the glory and comparative unity of the Arab World under Saladin was seen as the perfect symbol for the new unity sought by Arab nationalists, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser. For this reason, the Eagle of Saladin became the symbol of revolutionary Egypt, and was subsequently adopted by several other Arab states (Iraq, the Palestinian Territory, and Yemen).

Category:1130s births Category:1193 deaths Category:People from Tikrit Category:Ayyubid dynasty Category:Muslim generals Category:Crusades Category:Muslims of the Third Crusade Category:Kurdish people Category:Iranian people Category:History of the Kurdish people Category:History of Iraq Category:History of the Levant Category:Sultans of Egypt Category:History of Syria Category:Fertile Crescent

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.