- Order:

- Duration: 2:46

- Published: 05 Mar 2009

- Uploaded: 24 Apr 2011

- Author: XISouthernCrossIX

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.svg)

ASEAN.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

-Blue version.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

![The Abolitionist Project: Can Biotech Abolish Suffering Throughout the Living World? [UKH+] (1/3) The Abolitionist Project: Can Biotech Abolish Suffering Throughout the Living World? [UKH+] (1/3)](http://web.archive.org./web/20110517204515im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/2T1BcpWtIB4/0.jpg)

![The Abolitionist Project: Can Biotech Abolish Suffering Throughout the Living World? [UKH+] (2/3) The Abolitionist Project: Can Biotech Abolish Suffering Throughout the Living World? [UKH+] (2/3)](http://web.archive.org./web/20110517204515im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/rwZ8PXN0WF0/0.jpg)

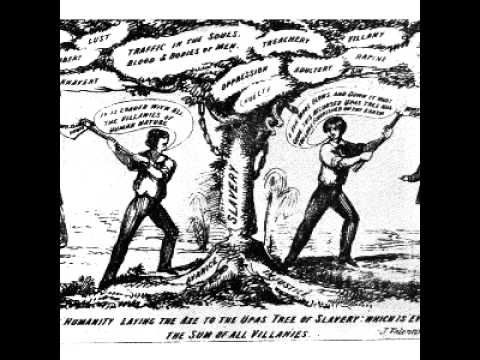

In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the new world, Spain enacted the first European law abolishing colonial slavery in the 16th century, although it was not to last. In the 17th century when Quaker and evangelical religious groups condemned it as un-Christian and the 18th century, when rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment criticized it for violating the rights of man. Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, they had little immediate effect on the centers of slavery: the West Indies, South America, and the Southern United States. The Somersett's case in 1772 that emancipated slaves in England, helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Britain banned the importation of African slaves in its colonies in 1807, and the United States followed in 1808. Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the French colonies abolished it 15 years later, while slavery in the United States was abolished in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Abolitionism in the West was preceded by the New Laws of the Indies in 1542, in which Emperor Charles V declared free all Native American slaves, abolishing slavery of these races, and declaring them citizens of the Empire with full rights. The move was inspired by writings of the Spanish monk Bartolome de las Casas and the School of Salamanca. Spanish settlers replaced the Native American slaves with enslaved laborers brought from Africa and thus did not abolish slavery altogether.

In Eastern Europe, abolitionism has played out in movements to end the enslavement of the Roma in Wallachia and Moldavia and to emancipate the serfs in Russia.

In East Asia, abolitionism was evidenced in, for instance, the writings of Yu Hyongwon, a 17th-century Korean Confucian scholar who wrote extensively against slave-holding in 17th-century Korea.

Today, child and adult slavery and forced labour are illegal in most countries, as well as being against international law.

Some of the first court cases to challenge the legality of slavery took place in Scotland. The cases were Montgomery v Sheddan (1756), Spens v Dalrymple (1769), and set the precedent of legal procedure in British courts that would later lead to successful outcomes for the plaintiffs.

William Wilberforce later took on the cause of abolition in 1787 after the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which he led the parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. He continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, which he lived to see in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in Britain at the beginning of the 17th century. But by the 18th century, traders began to import African and Indian and East Asian slaves to London and Edinburgh to work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians were documented in colonial records. They were not bought or sold in London, and their legal status was unclear until 1772, when the case of a runaway slave named James Somersett forced a legal decision. The owner, Charles Steuart, had attempted to abduct him and send him to Jamaica to work on the sugar plantations. While in London, Somersett had been baptised and his godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King's Bench, had to judge whether the abduction was legal or not under English Common Law, as there was no legislation for slavery in England.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772 Mansfield declared: "Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged." Although the exact legal implications of the judgement are actually unclear when analysed by lawyers, it was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law in England. This judgment emancipated the 10,000-14,000 slaves or possible slaves in England, who were mostly domestic servants. It also laid down the principle that slavery contracted in other jurisdictions (such as the North American colonies) could not be enforced in England.

The Somersett case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English speaking world, and helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. After reading about the Somersett's Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African in Scotland, left his master John Wedderburn. A similar case to Steuart's was brought by Wedderburn in 1776, with the same result: chattel slavery was ruled not to exist under the law of Scotland. Nonetheless, legally mandated, hereditary slavery of Scots in Scotland existed from 1606 until 1799, when colliers and salters were legally emancipated by an act of the Parliament of Great Britain (39 Geo.III. c56). A prior law enacted in 1775 (15 Geo.III. c. 28) was intended to end what the act referred to as "a state of slavery and bondage," but it was ineffectual, necessitating the 1799 act.

(c1729–1780) gained fame in his time as "the extraordinary Negro". To 18th-century British abolitionists, he became a symbol of the humanity of Africans and immorality of the slave trade.]]

Black people also played an important part in the movement for abolition. In Britain, Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiography was published in nine editions in his lifetime, campaigned tirelessly against the slave trade

One particular project of the abolitionists was the negotiation with African chieftains for the purchase of land in West African kingdoms for the establishment of 'Freetown' – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire and the United States, back in west Africa. This privately negotiated settlement, later part of Sierra Leone eventually became protected under a British Act of Parliament in 1807–8, after which British influence in West Africa grew as a series of negotiations with local Chieftains were signed to stamp out trading in slaves. These included agreements to permit British navy ships to intercept Chieftains' ships to ensure their merchants were not carrying slaves. "A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows", an illustration to J. G. Stedman's Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796).]]

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to Surinam as part of a military force sent out to subdue bosnegers, former slaves living in the inlands. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It became part of a large body of abolitionist literature.

The Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire. The Act imposed a fine of £100 for every slave found aboard a British ship. Such a law was bound to be eventually passed, given the increasingly powerful abolitionist movement. The timing might have been connected with the Napoleonic Wars raging at the time. At a time when Napoleon took the retrograde decision to revive slavery which had been abolished during the French Revolution and to send his troops to re-enslave the people of Haiti and the other French Caribbean possessions, the British prohibition of the slave trade gave the British Empire the high moral ground.

The act's intention was to entirely outlaw the slave trade within the British Empire, but the trade continued and captains in danger of being caught by the Royal Navy would often throw slaves into the sea to reduce the fine. In 1827, Britain declared that participation in the slave trade was piracy and punishable by death. Between 1808 and 1860, the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard. Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, for example against "the usurping King of Lagos", deposed in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.

On 28 August 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act was given Royal Assent, which paved the way for the abolition of slavery within the British Empire and its colonies. On 1 August 1834, all slaves in the British Empire were emancipated, but they were indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system which was abolished in two stages; the first set of apprenticeships came to an end on 1 August 1838, while the final apprenticeships were scheduled to cease on 1 August 1840, six years later.

On 1 August 1834, an unarmed group of mainly elderly Negroes being addressed by the Governor at Government House in Port of Spain, Trinidad, about the new laws, began chanting: "Pas de six ans. Point de six ans" ("Not six years. No six years"), drowning out the voice of the Governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish apprenticeship was passed and de facto freedom was achieved. Full emancipation for all was legally granted ahead of schedule on 1 August 1838, making Trinidad the first British colony with slaves to completely abolish slavery. The government set aside £20 million to cover compensation of slave owners across the Empire, but the former slaves received no compensation or reparations.

Convention, 1840" by Benjamin Haydon (1841).]]

As in other "New World" colonies, the Atlantic slave trade provided the French colonies with manpower for the sugar cane plantations. The French West Indies included Anguilla (briefly), Antigua and Barbuda (briefly), Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haïti, Montserrat (briefly), Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sint Eustatius (briefly), St Kitts and Nevis (St Kitts, but not Nevis), Trinidad and Tobago (Tobago only), Saint Croix (briefly), Saint-Barthélemy (until 1784 when became Swedish for nearly a century), the northern half of Saint Martin, and the current French overseas départements of Martinique and Guadeloupe in the Caribbean sea. (1754–1793), who organised the Society of the Friends of the Blacks in 1788 in the midst of the French Revolution.]] The slave trade was regulated by Louis XIV's Code Noir. The revolt of slaves in the largest French colony of St. Domingue in 1791 was the beginning of what became the Haïtian Revolution led by Toussaint L'Ouverture. The institution of slavery was first abolished in St. Domingue in 1793 by Sonthonax, who was the Commissioner sent to St. Domingue by the Convention, after the slave revolt of 1791, in order to safeguard the allegiance of the population to revolutionary France. The Convention, the first elected Assembly of the First Republic (1792–1804), then abolished slavery in law in France and its colonies on 4 February 1794. Abbé Grégoire and the Society of the Friends of the Blacks (Société des Amis des Noirs), led by Jacques Pierre Brissot, were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole. The first article of the law stated that "Slavery was abolished" in the French colonies, while the second article stated that "slave-owners would be indemnified" with financial compensation for the value of their slaves. The constitution of France passed in 1795 included in the declaration of the Rights of Man that slavery was abolished.

However, Napoleon did not include any declaration of the Rights of Man in the Constitution promulgated in 1799, and decided to re-establish slavery after becoming First Consul, promulgating the law of 20 May 1802 and sending military governors and troops to the colonies to impose it. On 10 May 1802, Colonel Delgrès launched a rebellion in Guadeloupe against Napoleon's representative, General Richepanse. The rebellion was repressed, and slavery was re-established. The news of this event sparked the rebellion that led to the loss of the lives of tens of thousands of French soldiers, a greater loss of civilian lives, and Haïti's gaining independence in 1804, and the consequential loss of the second most important French territory in the Americas, Louisiana, which was sold to the United States of America. The French governments refused to recognise Haiti and only did so in the 1830s when Haiti agreed to pay a substantial amount of reparations. Then, on 27 April 1848, under the Second Republic (1848–52), the decree-law Schœlcher again abolished slavery. The state bought the slaves from the colons (white colonists; Békés in Creole), and then freed them. (1849).]] At about the same time, France started colonising Africa. Its activities there included transferring the population to mines, forestry, and rubber plantations under isolated, harsh working conditions often compared to slavery.

Debates about the dimensions of colonialism continue. On 10 May 2001, the Taubira law officially acknowledge slavery and the Atlantic Slave Trade as a crime against humanity. 10 May was chosen as the day dedicated to recognition of the crime of slavery. Anti-colonial activists also want the French Republic to recognise African Liberation Day.

Although the crime of slavery was formally recognised, four years later, the conservative Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) voted on 23 February 2005 for a law to require teachers and textbooks to "acknowledge and recognise in particular the positive role of the French presence abroad, especially in North Africa." This resolution was met with public uproar and accusations of historic revisionism, both inside France and abroad. Because of this law, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, president of Algeria, refused to sign the envisioned "friendly treaty" with France. Famous writer Aimé Césaire, leader of the Négritude movement, refused to meet UMP leader Nicolas Sarkozy, who cancelled his planned visit to Martinique. President Jacques Chirac (UMP) repealed the controversial law at the beginning of 2006.

The 1860 presidential victory of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the spread of slavery to the Western United States, marked a turning point in the movement. Convinced that their way of life was threatened, the Southern states seceded from the Union, which led to the American Civil War. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves held in the Confederate States; the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1865) prohibited slavery throughout the country.

(1745–1829), who founded the New York Manumission Society in 1785.]] The principal organized bodies to advocate this reform were the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society and the New York Manumission Society. The last was headed by powerful politicians: John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, later Federalists and Aaron Burr, later Democratic-Republican Vice-President of the United States. That bill did not pass, because of controversy over the rights of freed slaves; every member of the Legislature, but one, voted for some version of it. New York did enact a bill in 1799, which did end slavery over time, but made no provision for the freedmen. New Jersey in 1804 was the last northern state to enact the gradual elimination slavery (again in a gradual fashion); there were still eighteen "perpetual apprentices" in New Jersey in the 1860 Census. Despite the actions of abolitionists, free blacks were subject to racial segregation in the North.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, agreement was reached that allowed the Federal government to abolish the importation of slaves into the United States, but not prior to 1808. By that time, all the states had passed individual laws abolishing or severely limiting the international buying or selling of slaves. The importation of slaves into the United States was officially banned on January 1, 1808. but not its internal slave trade.

The free black families began to thrive, together with African Americans free before the Revolution, mostly descendants of unions between working class white women and African men. By 1860, in Delaware 91.7 percent of the blacks were free, and 49.7 percent of those in Maryland. These first free families often formed the core of artisans, professionals, preachers and teachers in future generations. Northern teachers suspected of abolitionism were expelled from the South, and abolitionist literature was banned. Southerners rejected the denials of Republicans that they were abolitionists. They pointed to John Brown's attempt in 1859 to start a slave uprising as proof that multiple Northern conspiracies were afoot to ignite bloody slave rebellions. Although some abolitionists did call for slave revolts, no evidence of any other Brown-like conspiracy has been discovered. The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, "Northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests". However, many conservative Northerners were uneasy at the prospect of the sudden addition to the labor pool of a huge number of freed laborers who were used to working for very little, and thus seen as being willing to undercut prevailing wages.. The famous, "fiery" Abolitionist, Abby Kelley Foster, from Massachusetts, was considered an "ultra" abolitionist who believed in full civil rights for all black people. She held to the views that the freed slaves would colonize Liberia. Parts of the anti-slavery movement became known as "Abby Kellyism". She recruited Susan B Anthony to the movement.

Cincinnati's Black community sponsored founding the Wilberforce Colony, an initially successful settlement of African American immigrants to Canada. The colony was one of the first such independent political entities. It lasted for a number of decades and provided a destination for about 200 black families emigrating from a number of locations in the United States.

After O'Connell's failure, the American Repeal Associations broke up; but the Garrisonians rarely relapsed into the "bitter hostility" of American Protestants towards the Roman Church. Some antislavery men joined the Know Nothings in the collapse of the parties; but Edmund Quincy ridiculed it as a mushroom growth, a distraction from the real issues. Although the Know-Nothing legislature of Massachusetts honored Garrison, he continued to oppose them as violators of fundamental rights to freedom of worship. , the novel caught the public imagination just at a turning point in popular support for American abolition.]]

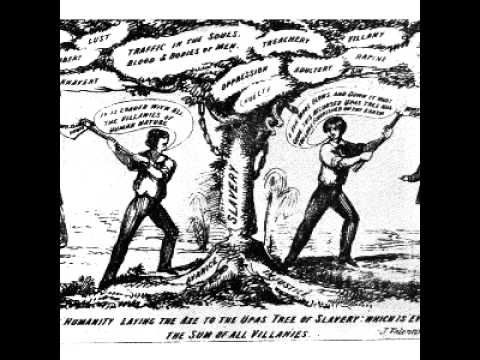

Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison repeatedly condemned slavery for contradicting the principles of freedom and equality on which the country was founded. In 1854, Garrison wrote:

I am a believer in that portion of the Declaration of American Independence in which it is set forth, as among self-evident truths, "that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Hence, I am an abolitionist. Hence, I cannot but regard oppression in every form – and most of all, that which turns a man into a thing – with indignation and abhorrence. Not to cherish these feelings would be recreancy to principle. They who desire me to be dumb on the subject of slavery, unless I will open my mouth in its defense, ask me to give the lie to my professions, to degrade my manhood, and to stain my soul. I will not be a liar, a poltroon, or a hypocrite, to accommodate any party, to gratify any sect, to escape any odium or peril, to save any interest, to preserve any institution, or to promote any object. Convince me that one man may rightfully make another man his slave, and I will no longer subscribe to the Declaration of Independence. Convince me that liberty is not the inalienable birthright of every human being, of whatever complexion or clime, and I will give that instrument to the consuming fire. I do not know how to espouse freedom and slavery together.

In The Struggle for Equality, historian James M. McPherson defines an abolitionist "as one who before the Civil War in the United States had agitated for the immediate, unconditional, and total abolition of slavery in the United States."

Although there were several groups that opposed slavery (such as the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage), at the time of the founding of the Republic, there were few states which prohibited slavery outright. The Constitution had several provisions which accommodated slavery, although none used the word. Passed unanimously by the Congress of the Confederation in 1787, the Northwest Ordinance forbade slavery in the Northwest Territory, a vast area which had previously belonged to individual states in which slavery was legal. (1652-1730), judge who wrote The Selling of Joseph (1700) which denounced the spread of slavery in the American colonies.]] American abolitionism began very early, well before the United States was founded as a nation. An early law abolishing slavery (but not temporary indentured servitude) in Rhode Island in 1652 floundered within 50 years. Samuel Sewall, a prominent Bostonian and one of the judges at the Salem Witch Trials, wrote The Selling of Joseph in protest of the widening practice of outright slavery as opposed to indentured servitude in the colonies. This is the earliest-recorded anti-slavery tract published in the future United States.

Abolitionists included those who joined the American Anti-Slavery Society or its auxiliary groups in the 1830s and 1840s as the movement fragmented. The fragmented anti-slavery movement included groups such as the Liberty Party; the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society; the American Missionary Association; and the Church Anti-Slavery Society. McPherson describes three types of abolitionists prior to the Civil War:

On the ideological spectrum, from immediate abolition on the Left to conservative antislavery on the Right, it is often hard to tell where "abolition" (which demanded unconditional emancipation and usually envisaged civil equality for the free slaves.) ended and "antislavery" or "free soil" (which desired only the containment of slavery and was ambivalent on the question of equality) began. In New England particularly, many free soilers were abolitionists at heart; in the mid-Atlantic states and even more in the old Northwest, political abolitionists tended to submerge their abolitionist identity in the broader but shallower stream of free soil.

In 1777, Vermont, not yet one of the United States, became the first jurisdiction in North America to prohibit slavery: slaves were not directly freed, but masters were required to remove slaves from Vermont. The first state to begin a gradual abolition of slavery was Pennsylvania, in 1780, and the process was very gradual indeed: all importation of slaves was prohibited, but none freed at first; only the slaves of masters who failed to register them with the state, along with the "future children" of enslaved mothers. Those enslaved in Pennsylvania before the 1780 law went into effect were not freed until 1847.

Massachusetts took an opposite and much more radical position. Its Supreme Court ruled in 1783, that a black man was, indeed, a man; and therefore free under the state's constitution.

All of the other states north of Maryland began gradual abolition of slavery between 1781 and 1804, based on the Pennsylvania model. Rhode Island had limited slave trading in 1774 (Virginia had also attempted to do so before the Revolution, but the Privy Council had vetoed the act), all the other northern states also limited the slave trade by 1786, and Georgia in 1798. These northern emancipation acts typically provided that slaves born before the law was passed would be freed at a certain age, and so remnants of slavery lingered; in New Jersey, a dozen "permanent apprentices" were recorded in the 1860 census. on 7 November 1837, which resulted in the murder of abolitionist Elijah Parish Lovejoy (1802-1837).]] The institution remained solid in the South, however and that region's customs and social beliefs evolved into a strident defense of slavery in response to the rise of a stronger anti-slavery stance in the North. In 1835 alone abolitionists mailed over a million pieces of anti-slavery literature to the south. In response southern legislators banned abolitionist literature and encouraged harassment of anyone distributing it. Anti-slavery sentiment among many people in the North was jolted by the murder of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a white man and editor of an abolitionist newspaper on 7 November 1837, by a pro-slavery mob which destroyed his printing press. The majority of Northerners rejected the extreme positions of the abolitionists; Abraham Lincoln, for example. Indeed many northern leaders including Lincoln, Stephen Douglas (the Democratic nominee in 1860), John C. Fremont (the Republican nominee in 1856), and Ulysses S. Grant married into slave owning southern families without any moral qualms.

(1808-1887), an individualist anarchist who wrote The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845).]] (1800–1859), abolitionist who advocated armed insurrection to overthrow the institution of slavery. He organized the Pottawatomie Massacre (1856) and was later executed for leading an unsuccessful 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.]] Abolitionism as a principle was far more than just the wish to limit the extent of slavery. Most Northerners recognized that slavery existed in the South and the Constitution did not allow the federal government to intervene there. Most Northerners favored a policy of gradual and compensated emancipation. After 1849 abolitionists rejected this and demanded it end immediately and everywhere. John Brown was the only abolitionist known to have actually planned a violent insurrection, though David Walker promoted the idea. The abolitionist movement was strengthened by the activities of free African-Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old Biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament.

African-American activists and their writings were rarely heard outside the black community; however, they were tremendously influential to some sympathetic white people, most prominently the first white activist to reach prominence, William Lloyd Garrison, who was its most effective propagandist. Garrison's efforts to recruit eloquent spokesmen led to the discovery of ex-slave Frederick Douglass, who eventually became a prominent activist in his own right. Eventually, Douglass would publish his own, widely distributed abolitionist newspaper, the North Star.

In the early 1850s, the American abolitionist movement split into two camps over the issue of the United States Constitution. This issue arose in the late 1840s after the publication of The Unconstitutionality of Slavery by Lysander Spooner. The Garrisonians, led by Garrison and Wendell Phillips, publicly burned copies of the Constitution, called it a pact with slavery, and demanded its abolition and replacement. Another camp, led by Lysander Spooner, Gerrit Smith, and eventually Douglass, considered the Constitution to be an antislavery document. Using an argument based upon Natural Law and a form of social contract theory, they said that slavery existed outside of the Constitution's scope of legitimate authority and therefore should be abolished.

Another split in the abolitionist movement was along class lines. The artisan republicanism of Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright stood in stark contrast to the politics of prominent elite abolitionists such as industrialist Arthur Tappan and his evangelist brother Lewis. While the former pair opposed slavery on a basis of solidarity of "wage slaves" with "chattel slaves", the Whiggish Tappans strongly rejected this view, opposing the characterization of Northern workers as "slaves" in any sense. (Lott, 129–130) being adored by an enslaved mother and child as he walks to his execution.]] Many American abolitionists took an active role in opposing slavery by supporting the Underground Railroad. This was made illegal by the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Nevertheless, participants like Harriet Tubman, Henry Highland Garnet, Alexander Crummell, Amos Noë Freeman and others continued with their work. Abolitionists were particularly active in Ohio, where some worked directly in the Underground Railroad. Since the state shared a border with slave states, it was a popular place for slaves' escaping across the Ohio River and up its tributaries, where they sought shelter among supporters who would help them move north to freedom. Two significant events in the struggle to destroy slavery were the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. In the South, members of the abolitionist movement or other people opposing slavery were often targets of lynch mob violence before the American Civil War.

Numerous known abolitionists lived, worked, and worshipped in Downtown Brooklyn, from Henry Ward Beecher, who auctioned slaves into freedom from the pulpit of Plymouth Church, to Nathan Egelston, a leader of the African and Foreign Antislavery Society, who also preached at Bridge Street AME and lived on Duffield Street. His fellow Duffield Street residents, Thomas and Harriet Truesdell were leading members of the Abolitionist movement. Mr. Truesdell was a founding member of the Providence Anti-slavery Society before moving to Brooklyn in 1851. Harriet Truesdell was also very active in the movement, organizing an antislavery convention in Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia. The Tuesdell's lived at 227 Duffield Street. Another prominent Brooklyn-based abolitionist was Rev. Joshua Leavitt, trained as a lawyer at Yale who stopped practicing law in order to attend Yale Divinity School, and subsequently edited the abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator and campaigned against slavery, as well as advocating other social reforms. In 1841 Leavitt published his The Financial Power of Slavery, which argued that the South was draining the national economy due to its reliance on slavery.

After the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January 1863, abolitionists continued to pursue the freedom of slaves in the remaining slave states, and to better the conditions of black Americans generally. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 officially ended slavery in the United States.

==National abolition dates== Slavery was abolished in these nations in these years: Persia: Cyrus the Great, the King of Persia, declared (around 600 BCE) that all slaves would be freed, one of many unheard of liberal reforms in his time. Hungary: Stephen I of Hungary, the first Hungarian Christian king, declared in his laws (near the year 1000) that any slave that lives, stays or enters the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary would become free immediately. Sweden: Magnus IV of Sweden declared the end of thralldom in 1335 "for thralls born by Christian parents in the thing areas of Västergötland and Värend". Swedish participation in the transatlantic slave trade was forbidden in 1813, and in 1847, slavery was abolished, after an initial decision taken in 1846. (The last legally owned slaves in the Swedish colony of St Barthélemy were bought by the state and freed on 9 October 1847.)

2007 witnessed major exhibitions in British museums and galleries to mark the anniversary of the 1807 abolition act – 1807 Commemorated 2008 marks the 201st anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade in the British Empire. It also marks the 175th anniversary of the Abolition of Slavery in the British Empire.

The Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa held a major international conference entitled, "Routes to Freedom: Reflections on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade", from 14 to 16 March 2008. Actor and human rights activist Danny Glover delivered the keynote speech announcing the creation of two major scholarships intended for University of Ottawa law students specializing in international law and social justice at the conference's gala dinner.

Brooklyn, New York has begun work on commemorating the abolitionist movement in New York.

Although outlawed in most countries, slavery is nonetheless practiced secretly in many parts of the world. Enslavement still takes place in the United States, Europe, and Latin America, as well as parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. There are an estimated 27 million victims of slavery worldwide. In Mauritania alone, estimates are that up to 600,000 men, women and children, or 20% of the population, are enslaved. Many of them are used as bonded labour.

Modern-day abolitionists have emerged over the last several years, as awareness of slavery around the world has grown, with groups such as Anti-Slavery International, the American Anti-Slavery Group, International Justice Mission, and Free the Slaves working to rid the world of slavery. Zach Hunter, for example, began a movement called Loose Change to Loosen Chains when he was in seventh grade. Also featured on CNN and other national news organizations, Hunter has gone on to help inspire other teens and young adults to take action against injustice with his books, Be the Change and Generation Change.

In the United States, The Action Group to End Human Trafficking and Modern-Day Slavery is a coalition of NGOs, foundations and corporations working to develop a policy agenda for abolishing slavery and human trafficking. Since 1997, the United States Department of Justice has, through work with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, prosecuted six individuals in Florida on charges of slavery in the agricultural industry. These prosecutions have led to freedom for over 1000 enslaved workers in the tomato and orange fields of South Florida. This is only one example of the contemporary fight against slavery worldwide. Slavery exists most widely in agricultural labor, apparel and sex industries, and service jobs in some regions.

In 2000, the United States passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) "to combat trafficking in persons, especially into the sex trade, slavery, and involuntary servitude." The TVPA also "created new law enforcement tools to strengthen the prosecution and punishment of traffickers, making human trafficking a Federal crime with severe penalties."

The United States Department of State publishes the annual Trafficking in Persons Report, identifying countries as either Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List or Tier 3, depending upon three factors: "(1) The extent to which the country is a country of origin, transit, or destination for severe forms of trafficking; (2) The extent to which the government of the country does not comply with the TVPA's minimum standards including, in particular, the extent of the government's trafficking-related corruption; and (3) The resources and capabilities of the government to address and eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons."

Category:Political movements Category:African diaspora history Category:Slavery

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Frederick Douglass |

|---|---|

| Birth date | February 1818 |

| Birth place | Talbot County, Maryland, United States |

| Death date | February 20, 1895 (aged about 78) |

| Death place | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, author, editor, diplomat |

| Spouse | Anna Murray (c. 1839)Helen Pitts (1884) |

| Parents | Harriet Bailey and perhaps Aaron Anthony |

| Political party | Republican |

| Children | Charles Remond DouglassRosetta DouglassLewis Henry DouglassFrederick Douglass Jr.Annie Douglass (died at 10) |

| Signature | Douglass Signature.svg |

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining renown for his dazzling oratory and incisive antislavery writing. He stood as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that slaves did not have the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. He became a major speaker for the cause of abolition.

In addition to his oratory, Douglass wrote several autobiographies, eloquently describing his life as a slave, and his struggles to be free. His classic autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, is one of the best known accounts of American slavery.

After the Civil War, Douglass remained very active in America's struggle to reach its potential as a "land of the free". Douglass actively supported women's suffrage. Following the war, he worked on behalf of equal rights for freedmen, and held multiple public offices.

Douglass was a firm believer in the equality of all people, whether black, female, Native American, or recent immigrant. He was fond of saying, "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

The identity of his father is obscure. Douglass originally stated that he was told his father was a white man, perhaps his master Aaron Anthony. Later he said he knew nothing of his father's identity. At age seven, Douglass was separated from his grandmother and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Anthony worked as overseer. When Anthony died, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld. She sent Douglass to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore.

When Douglass was about twelve years old, Hugh Auld's wife Sophia started teaching him the alphabet despite the fact that it was against the law to teach slaves to read. Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, she treated Douglass like one human being ought to treat another. When Hugh Auld discovered her activity, he strongly disapproved, saying that if a slave learned to read, he would become dissatisfied with his condition and desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this statement as the "first decidedly antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. As detailed in his autobiography, Douglass succeeded in learning to read from white children in the neighborhood and by observing the writings of men with whom he worked. Mrs.Auld one day saw Douglass reading a newspaper she ran over to him and snatched it from him, with a face that said education and slavery were incompatible with each other.

He continued, secretly, to teach himself how to read and write. Douglass is noted as saying that "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom." As Douglass learned and began to read newspapers, political materials, and books of every description, he was exposed to a new realm of thought that led him to question and then condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, which he discovered at about age twelve, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights.

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly Sunday school. As word spread, the interest among slaves in learning to read was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. For about six months, their study went relatively unnoticed. While Freeland was complacent about their activities, other plantation owners became incensed that their slaves were being educated. One Sunday they burst in on the gathering, armed with clubs and stones, to disperse the congregation permanently.

In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh after a dispute ("[A]s a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass wrote). Dissatisfied with Douglass, Thomas Auld sent him to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker." There Douglass was whipped regularly. The sixteen-year-old Douglass was indeed nearly broken psychologically by his ordeal under Covey, but he finally rebelled against the beatings and fought back. After losing a confrontation with Douglass, Covey never tried to beat him again.

In 1837, Douglass met Anna Murray, a free black in Baltimore. They married soon after he obtained his freedom.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Dressed in a sailor's uniform, he carried identification papers provided by a free black seaman. He crossed the Susquehanna River by ferry at Havre de Grace, then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there he went by steamboat to "Quaker City" (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and continued to New York; the whole journey took less than 24 hours.

Frederick Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York City: }}

After he told his story, he was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. Douglass was inspired by Garrison and later stated that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments [of the hatred of slavery] as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and wrote of him in The Liberator. Several days later, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention in Nantucket. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his rough life as a slave.

In 1843, Douglass participated in the American Anti-Slavery Society's Hundred Conventions project, a six-month tour of meeting halls throughout the Eastern and Midwestern United States.

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 Narrative, which was his biggest seller, was followed by My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855. In 1881, after the Civil War, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Douglass' friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many other former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the Cambria for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and arrived in Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine was beginning.

Douglass spent two years in the United Kingdom and Ireland, where he gave many lectures, in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation"; an example was his hugely popular London Reception Speech, which Douglass delivered at Alexander Fletcher's Finsbury Chapel in May 1846. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man." He met and befriended the Irish nationalist Daniel O'Connell.

It was during this trip that Douglass became officially free, when Irish and British supporters arranged to purchase his freedom from his owner. British sympathizers led by Ellen Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne collected the money needed to purchase his freedom. In 1846 Douglass met with Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British abolitionists who persuaded Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain and its colonies.

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address to the Ladies of the Rochester Anti Slavery Sewing Society, which eventually became known as "What to the slave is the 4th of July?" It was a blistering attack on the hypocrisy of the United States in general and the Christian church in particular.

Douglass' change of position on the Constitution was one of the most notable incidents of the division in the abolitionist movement after the publication of Spooner's book The Unconstitutionality of Slavery in 1846. This shift in opinion, and other political differences, created a rift between Douglass and Garrison. Douglass further angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.

Douglass believed that education was key for African Americans to improve their lives. For this reason, he was an early advocate for desegregation of schools. In the 1850s, he was especially outspoken in New York. While the ratio of African American to white students there was 1 to 40, African Americans received education funding at a ratio of only 1 to 1,600. This meant that the facilities and instruction for African-American children were vastly inferior. Douglass criticized the situation and called for court action to open all schools to all children. He stated that inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

Douglass was acquainted with the radical abolitionist John Brown but disapproved of Brown's plan to start an armed slave rebellion in the South. Brown visited Douglass' home two months before he led the raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry. After the raid, Douglass fled for a time to Canada, fearing guilt by association and arrest as a co-conspirator. Douglass believed that the attack on federal property would enrage the American public. Douglass later shared a stage at a speaking engagement in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter, the prosecutor who successfully convicted Brown.

In March 1860, Douglass' youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, while he was still in England. Douglass returned from England the following month. He took a route through Canada to avoid detection.

President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory. (Slaves in Union-held areas and Northern states would become freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky...we were watching...by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day...we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."

With the North no longer obliged to return slaves to their owners in the South, Douglass fought for equality for his people. He made plans with Lincoln to move the liberated slaves out of the South. During the war, Douglass helped the Union by serving as a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. His son Frederick Douglass Jr. also served as a recruiter and his other son, Lewis Douglass, fought for the 54th Massachusetts Regiment at the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was outlawed by the post-war (1865) ratification of the 13th Amendment. The 14th Amendment provided for citizenship and equal protection under the law. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race.

The crowd, roused by his speech, gave him a standing ovation. A long-told anecdote claims that the widow Mary Lincoln gave Lincoln's favorite walking stick to Douglass in appreciation. Lincoln's walking stick still rests in Douglass' house known as Cedar Hill. It is both a testimony and a tribute to the effect of Douglass' powerful oratory.

In 1868, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant. President Grant signed into law the Klan Act and the second and third Enforcement Acts. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending habeas corpus in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states; under his leadership over 5,000 arrests were made and the Ku Klux Klan received a serious blow. Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites, but Frederick Douglass praised him. An associate of Douglass wrote of Grant that African Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of his name, fame and great services."

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. He was nominated without his knowledge. During the campaign, he neither campaigned for the ticket nor acknowledged that he had been nominated. , Douglass' house in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C., is preserved as a National Historic Site.]] Douglass continued his speaking engagements. On the lecture circuit, he spoke at many colleges around the country during the Reconstruction era, including Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 1873. He continued to emphasize the importance of voting rights and exercise of suffrage. In a speech delivered on 15 November 1867, Douglass said "A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex".

White insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Through the years, armed insurgency took different forms, the last as powerful paramilitary groups such as the White League and the Red Shirts during the 1870s in the Deep South. They operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", turning out Republican officeholders and disrupting elections. Their power continued to grow in the South; more than 10 years after the end of the war, white Democrats regained political power in every state of the former Confederacy and began to reassert white supremacy. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late 19th century laws imposing segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise African Americans. From 1890–1908, white Democrats passed new constitutions and statutes in the South that created requirements for voter registration and voting that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites. This disfranchisement and segregation were enforced for more than six decades into the 20th century.

Douglass's stump speech for 25 years after the end of the Civil War was to emphasize work to counter the racism that was then prevalent in unions.

In 1877, Douglass bought their final home in Washington D.C., on a hill above the Anacostia River. He and Anna named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). They expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms, and included a china closet. One year later, Douglass purchased adjoining lots and expanded the property to 15 acres (61,000 m²). The home has been designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

His wife, Anna Murray Douglass, died in 1882, leaving him with a sense of great loss and depressed for a time. He found new meaning from working with activist Ida B. Wells.

(sitting). The woman standing is her sister Eva Pitts.]] In 1884, Douglass married again, to Helen Pitts, a white feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts, Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College (then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), she worked on a radical feminist publication named Alpha while living in Washington, D.C. The couple faced a storm of controversy with their marriage, since Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Her family stopped speaking to her; his was bruised, as his children felt his marriage was a repudiation of their mother. But feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton congratulated the couple. The new couple traveled to England, France, Italy, Egypt and Greece from 1886 to 1887.

In 1877, Douglass was appointed a United States Marshal. In 1881, he was appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia.

At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States in a major party's roll call vote.

He was appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti (1889–1891). In 1892 the Haitian government appointed Douglass as its commissioner to the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition. He spoke for Irish Home Rule and the efforts of leader Charles Stewart Parnell in Ireland. He briefly revisited Ireland in 1886.

Also in 1892, Douglass constructed rental housing for blacks, now known as Douglass Place, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Frederick Douglass to his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Numerous public schools have been named in his honor.

In successive autobiographies, Douglass gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817. He adopted February 14 as his birthday because his mother Harriet Bailey used to call him her "little valentine". Douglass was born at

;For young readers

;Documentary films

Resource Guides

Biographical information

Category:1818 births Category:1895 deaths Category:19th-century American newspaper editors Category:19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) Category:African American United States presidential candidates Category:African American United States vice-presidential candidates Category:African American memoirists Category:African American publishers (people) Category:African Americans' rights activists Category:African American writers Category:American Methodists Category:American abolitionists Category:American autobiographers Category:American newspaper founders Category:American slaves Category:American suffragists Category:Anglican saints Category:Burials at Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester Category:Deaths from myocardial infarction Category:Journalists from Upstate New York Category:People from Baltimore, Maryland Category:People from Rochester, New York Category:People from Talbot County, Maryland Category:United States Marshals Category:United States ambassadors to Haiti Category:United States ambassadors to the Dominican Republic Category:United States presidential candidates, 1888 Category:United States vice-presidential candidates, 1872

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Abraham Lincoln |

|---|---|

| Nationality | American |

| Alt | Iconic black and white photograph of Lincoln showing his head and shoulders. |

| Order | 16th President of the United States |

| Term start | March 4, 1861 |

| Term end | April 15, 1865 |

| Predecessor | James Buchanan |

| Successor | Andrew Johnson |

| State2 | Illinois |

| District2 | 7th |

| Term start2 | March 4, 1847 |

| Term end2 | March 3, 1849 |

| Predecessor2 | John Henry |

| Successor2 | Thomas L. Harris |

| Birth date | February 12, 1809 |

| Birth place | Hardin County, Kentucky |

| Death date | April 15, 1865 |

| Death place | Washington, D.C. |

| Restingplace | Oak Ridge CemeterySpringfield, Illinois |

| Spouse | Mary Todd Lincoln |

| Children | Robert Todd Lincoln Edward Lincoln Willie Lincoln Tad Lincoln |

| Profession | LawyerPolitician |

| Religion | See: Abraham Lincoln and religion |

| Party | Whig (1832–1854) Republican (1854–1865) |

| Vicepresident | Hannibal Hamlin (1861–1865)Andrew Johnson (1865) |

| Signature | Abraham Lincoln Signature.svg |

| Signature alt | Cursive signature in ink |

| Branch | Illinois Militia |

| Serviceyears | 1832 |

| Battles | Black Hawk War |

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) served as the 16th President of the United States from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led the country through its greatest internal crisis, the American Civil War, preserved the Union, and ended slavery. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, he was mostly self-educated. He became a country lawyer, an Illinois state legislator, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives, but failed in two attempts at a seat in the United States Senate. He was an affectionate, though often absent, husband, and father of four children.

Lincoln was an outspoken opponent of the expansion of slavery in the United States, which he deftly articulated in his campaign debates and speeches. As a result, he secured the Republican nomination and was elected president in 1860. As president he concentrated on the military and political dimensions of the war effort, always seeking to reunify the nation after the secession of the eleven Confederate States of America. He vigorously exercised unprecedented war powers, including the arrest and detention, without trial, of thousands of suspected secessionists. He issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and promoted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery.

Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including Ulysses S. Grant. He brought leaders of various factions of his party into his cabinet and pressured them to cooperate. He defused a confrontation with Britain in the Trent affair late in 1861. Under his leadership, the Union took control of the border slave states at the start of the war and tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another, until finally Grant succeeded in 1865. A shrewd politician deeply involved with patronage and power issues in each state, he reached out to War Democrats and managed his own re-election in the 1864 presidential election.

As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican party, Lincoln came under attack from all sides. Radical Republicans wanted harsher treatment of the South, Democrats desired more compromise, and secessionists saw him as their enemy. Lincoln fought back with patronage, by pitting his opponents against each other, and by appealing to the American people with his powers of oratory; for example, his Gettysburg Address of 1863 became one of the most quoted speeches in history. It was an iconic statement of America's dedication to the principles of nationalism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. At the close of the war, Lincoln held a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to speedily reunite the nation through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. Just six days after the decisive surrender of the commanding general of the Confederate army, Lincoln fell victim to an assassin — the first President to suffer such a fate. Lincoln has consistently been ranked by scholars as one of the greatest U.S. Presidents.

Little is known about Lincoln's ancestors. Historical investigations have traced his family back to Samuel Lincoln, an apprentice weaver who arrived in Hingham, Massachusetts, from Norfolk, England, in 1637. However, Lincoln himself was only able to trace his heritage back as far as his paternal grandfather and namesake, Abraham Lincoln, a local militia captain, and a substantial landholder with an inherited 200 acre estate in Rockingham County, Virginia) Mordecai's marksmanship with a rifle saved Thomas from the same fate. As the eldest son, by law, Mordecai inherited his father's entire estate.

Thomas became a poor but respected citizen of rural Kentucky. He bought and sold several farms, including the Sinking Spring Farm. The family belonged to a Separate Baptists church, which had high moral standards and opposed alcohol, dancing, and slavery, though Lincoln himself never joined a church. In 1816, the Lincoln family lost their lands because of a faulty title and made a new start in Perry County, Indiana (now Spencer County). Lincoln later noted that this move was "partly on account of slavery" but mainly due to land title difficulties.

When Lincoln was nine, his 34-year-old mother died of milk sickness. However, he became increasingly distant from his father. Lincoln regretted his father's lack of education, and did not like the hard labor associated with frontier life. Still, he willingly took responsibility for all chores expected of him as a male in the household; he became an adept axeman in his work building rail fences. Lincoln also agreed with the customary obligation of a son to give his father all earnings from work done outside the home until age 21. In later years, he occasionally loaned his father money.

In 1830, fearing a milk sickness outbreak, the family settled on public land in Macon County, Illinois. In 1831, when his father relocated the family to a new homestead in Coles County, Illinois, 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, canoeing down the Sangamon River to the village of New Salem in Sangamon County. In spring 1831, hired by New Salem businessman Denton Offutt and accompanied by friends, he took goods by flatboat from New Salem to New Orleans via the Sangamon, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers. After arriving in New Orleans—and witnessing slavery firsthand—he walked back home.

Lincoln's formal education consisted of approximately 18 months of classes from several itinerant teachers; he was mostly self-educated and was an avid reader. He attained a reputation of brawn and audacity after a very competitive wrestling match, to which he was challenged by the renowned leader of a group of ruffians, "the Clary's Grove boys." His family and neighbors considered him to be lazy. Lincoln avoided hunting and fishing out of an aversion to killing animals.

Lincoln's first romantic interest was Ann Rutledge, whom he met when he first moved to New Salem; by 1835, they were in a relationship but not formally engaged. Ann wanted to notify a former love before "consummating the engagement to Mr. L. with marriage." Rutledge died, however, on August 25, most likely of typhoid fever.

In the early 1830s, he met Mary Owens from Kentucky when she was visiting her sister. Late in 1836, Lincoln agreed to a match with Mary if she returned to New Salem. Mary did return in November 1836, and Lincoln courted her for a time; however, they both had second thoughts about their relationship. On August 16, 1837, Lincoln wrote Mary a letter from his law practice in Springfield, suggesting he would not blame her if she ended the relationship. She never replied, and the courtship was over.

In 1840, Lincoln became engaged to Mary Todd, who was from a wealthy slave-holding family in Lexington, Kentucky. They met in Springfield in December 1839, and were engaged sometime in late December. A wedding was set for January 1, 1841, but the couple split as the wedding approached. While preparing for the nuptials and having cold feet again, Lincoln, when asked where he was going, replied, "To hell, I suppose." photo depicts President Lincoln reading a book with his youngest son, Tad]] In 1844, the couple bought a house in Springfield near Lincoln's law office. Mary Todd Lincoln worked diligently in their home, assuming household duties which had been performed for her in her own family. She also made efficient use of the limited funds available from her husband's law practice. One evening, Mary asked Lincoln four times to restart the fire and, getting no reaction, as he was absorbed in his reading, she grabbed a piece of firewood and rapped him on the head. The Lincolns had a budding family, with the birth of Robert Todd Lincoln in 1843, and Edward Baker Lincoln in 1846. According to a house girl, Abraham "was remarkably fond of children" and the Lincolns were not thought to be strict with their children.

Robert was the only child of the Lincolns to live past the age of 18. Edward Lincoln died on February 1, 1850, in Springfield, likely of tuberculosis. The Lincolns' grief over this loss was somewhat assuaged by the birth of William "Willie" Wallace Lincoln nearly 11 months later, on December 21. However, Willie died of a fever at the age of 11 on February 20, 1862, in Washington, D.C., during President Lincoln's first term. The Lincolns' fourth son, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln, was born on April 4, 1853 and outlived his father, but died at the age of 18 on July 16, 1871, in Chicago.

The death of their sons had profound effects on both parents. Later in life, Mary struggled with the stresses of losing her husband and sons; Robert Lincoln committed her to a mental health asylum in 1875. Abraham Lincoln suffered from "melancholy", a condition which now may be referred to as clinical depression.

Lincoln's father-in-law was based in Lexington, Kentucky; he and most of the Todd family were slave owners and some members were slave traders. Lincoln was close to the Todds and he and his family occasionally visited the Todd estate in Lexington. Lincoln's connections in Lexington could have accelerated his ambitions, but he remained in Illinois, where, to his liking, slavery was almost nonexistent.

Lincoln served as New Salem's postmaster and, after more dedicated self-study, as county surveyor. In 1834, he won election to the state legislature after a bipartisan campaign, though he ran as a Whig. He then decided to become a lawyer, and began teaching himself law by reading Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and others. Lincoln's description of his learning method was: "I studied with nobody." Admitted to the bar in 1837, he moved to Springfield, Illinois, and began to practice law under John T. Stuart, Mary Todd's cousin. Lincoln became an able and successful lawyer with a reputation as a formidable adversary during cross-examinations and closing arguments. In 1841, he partnered with Stephen Logan until 1844, when he began his practice with William Herndon, whom Lincoln thought "a studious young man." He served four successive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives as a Whig representative from Sangamon County.

In the 1835–1836 legislative session, he voted to continue the restriction on suffrage to white males only while removing the condition of land ownership. He was known for his "free soil" stance of opposing both slavery and abolitionism. He first articulated this in 1837, saying the "institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils." He closely followed Henry Clay in supporting the American Colonization Society program of making the abolition of slavery practical by helping the freed slaves return to Liberia in Africa.

From the early 1830s, Lincoln was a steadfast Whig and professed to friends in 1861, "I have always been an old-line Henry Clay Whig." The party favored economic modernization in banking, railroads, and internal improvements, and supported urbanization as well as protective tariffs, and Lincoln supported these positions.

In 1846, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served one two-year term. He was the only Whig in the Illinois delegation, but showed his party loyalty by participating in almost all votes and making speeches that echoed the party line. Lincoln developed a plan to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, with compensation for the owners and a popular vote on the matter, but dropped it when he could not get enough Whig supporters. He used his office as an opportunity to speak out against the Mexican–American War, which he attributed to President Polk's desire for "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood."

Lincoln articulated his opposition to Polk by drafting and introducing his Spot Resolutions. The war had begun with a violent confrontation on territory disputed by Mexico and the U.S., but Polk insisted that Mexican soldiers had "invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our own soil." Lincoln demanded that Polk show Congress the exact spot on which blood had been shed, and prove that the spot was on American soil.

Realizing Clay was unlikely to win the presidency, Lincoln endorsed war hero General Zachary Taylor for the Whig nomination in the 1848 presidential election. Some of Lincoln's statements he would later regret, especially his attack on the presidential war-making powers. Taylor won and Lincoln wanted to be Commissioner of the General Land Office, but that lucrative patronage job went to a rival in Illinois. The administration offered him the consolation prize of secretary or governor of the Oregon Territory. The territory was a Democratic stronghold and acceptance would have ended his legal and political career in Illinois, so he declined.

In 1851, he represented Alton & Sangamon Railroad in a dispute with one of its shareholders, James A. Barret, who had refused to pay the balance on his pledge to buy shares in the railroad, on the grounds that the company had changed its original train route. Lincoln successfully argued that the railroad company was not bound by its original charter in existence at the time of Barret's pledge; the charter was amended in the public interest, to provide a newer, superior and less expensive route, and the corporation retained the right to demand Mr. Barret's payment. The decision by the Illinois Supreme Court has been cited by numerous other courts in the nation. From 1853 to 1860 Lincoln was a lawyer and lobbyist for the Illinois Central Railroad, one of the largest corporations in the world at that time.

Lincoln's most notable criminal trial occurred in 1858 when he defended William "Duff" Armstrong, who was on trial for the murder of James Preston Metzker. The case is famous for Lincoln's use of a fact established by judicial notice in order to challenge an eyewitness' credibility. After an opposing witness testified seeing the crime in the moonlight, Lincoln produced a Farmers' Almanac showing the moon was at a low angle, drastically reducing visibility. Based on this evidence, Armstrong was acquitted.

On October 16, 1854, in his "Peoria Speech," Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery which he repeated en route to the presidency. Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice, he said the Kansas Act had a "'declared' indifference, but as I must think, a covert 'real' zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world..."

In late 1854, Lincoln decided to run as a Whig for an Illinois seat in the United States Senate, which was, at that time, elected by the state legislature. After leading in the first six rounds of voting in the Illinois assembly, once his support began to dwindle, Lincoln instructed his backers to vote for Lyman Trumbull, who defeated opponent Joel Aldrich Matteson. The Whigs had been irreparably split by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Lincoln said, "I think I am a Whig, but others say there are no Whigs, and that I am an abolitionist, even though I do no more than oppose the extension of slavery." Drawing on remnants of the old Whig party, and on disenchanted Free Soil, Liberty, and Democratic party members, he was instrumental in forging the shape of the new Republican Party. At the Republican convention in 1856, Lincoln placed second in the contest to become the party's candidate for Vice-President.

In 1857–58, Douglas broke with President Buchanan, leading to a fight for control of the Democratic Party. Some eastern Republicans even favored the re-election of Douglas for the Senate in 1858, since he had led the opposition to the Lecompton Constitution, which would have admitted Kansas as a slave state. In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its controversial pro-slavery decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford; Chief Justice Taney opined that blacks were not citizens, and derived no rights from the Declaration of Independence or Constitution. Lincoln, though strong in his disagreement with the Court's opinion, was as a lawyer unequivocal in his deference to the Court's authority. Lincoln historian David Herbert Donald provides Lincoln's immediate reaction to the decision, showing his evolving position on slavery: "The authors of the Declaration of Independence never intended 'to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity', but they 'did consider all men created equal—equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness'." After the state Republican party convention nominated him for the U.S. Senate in 1858 (the second instance of this in the country), Lincoln then delivered his famous speech: "'A house divided against itself cannot stand'.(Mark 3:25) I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other." The speech created an evocative image of the danger of disunion caused by the slavery debate, and rallied Republicans across the North. The stage was then set for the campaign for statewide election of the Illinois legislature which would, in turn, select Lincoln or Douglas as its U.S. Senator.

Though the Republican legislative candidates won more popular votes, the Democrats won more seats, and the legislature re-elected Douglas to the Senate. Despite the bitterness of the defeat for Lincoln, his articulation of the issues gave him a national political reputation. In May 1859, Lincoln purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, a German-language newspaper which was consistently supportive; most of the state's 130,000 German Americans voted Democratic but there was Republican support that a German-language paper could mobilize.

On February 27, 1860, New York party leaders invited Lincoln to give a speech at Cooper Union to a group of powerful Republicans. Lincoln argued that the Founding Fathers had little use for popular sovereignty and had repeatedly sought to restrict slavery. Lincoln insisted the moral foundation of the Republicans required opposition to slavery, and rejected any "groping for some middle ground between the right and the wrong." Despite his inelegant appearance—many in the audience thought him awkward and even ugly—Lincoln demonstrated an intellectual leadership that brought him into the front ranks of the party and into contention for the Republican presidential nomination. Journalist Noah Brooks reported, "No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience." Donald described the speech as a "superb political move for an unannounced candidate, to appear in one rival's (William H. Seward) own state at an event sponsored by the second rival's (Salmon P. Chase) loyalists, while not mentioning either by name during its delivery." In response to an inquiry about his presidential intentions, Lincoln said, "The taste is in my mouth a little."

, Horace Greeley, ed]]

On May 9–10, 1860, the Illinois Republican State Convention was held in Decatur. Lincoln's followers organized a campaign team led by David Davis, Norman Judd, Leonard Swett, and Jesse DuBois, and Lincoln received his first endorsement to run for the presidency. Tapping on the distorted legend of his pioneering days with his father, Lincoln's supporters adopted the label of "The Rail Candidate." On May 18, at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln became the Republican candidate on the third ballot, beating candidates such as William H. Seward and Salmon P. Chase. Former Democrat Hannibal Hamlin of Maine received the nomination for Vice President to balance the ticket. Lincoln's nomination has been attributed in part to his moderate views on slavery, as well as his support of internal improvements and the protective tariff. In terms of the actual balloting, Pennsylvania put him over the top. (Lincoln made known to Pennsylvania iron interests his support for protective tariffs.) Lincoln's managers had been adroitly focused on this delegation as well as the others, while following Lincoln's strong dictate to "Make no contracts that bind me."

Most Republicans agreed with Lincoln that the North was the aggrieved party of the Slave Power, as it tightened its grasp on the national government with the Dred Scott decision and the presidency of James Buchanan. Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln doubted the prospects of civil war, and his supporters rejected claims that his election would incite secession. Meanwhile, Douglas was selected as the candidate of the Northern Democrats, with Herschel Vespasian Johnson as the vice-presidential candidate. Delegates from 11 slave states walked out of the Democratic convention, disagreeing with Douglas's position on popular sovereignty, and ultimately selected John C. Breckinridge as their candidate.

As Douglas and the other candidates went through with their campaigns, Lincoln was the only one of them who gave no speeches. Instead, he monitored the campaign closely and relied on the enthusiasm of the Republican Party. The party did the leg work that produced majorities across the North, and produced an abundance of campaign posters, leaflets, and newspaper editorials. There were thousands of Republican speakers who focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, emphasizing his childhood poverty. The goal was to demonstrate the superior power of "free labor," whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts. The Republican Party's production of campaign literature dwarfed the combined opposition; a Chicago Tribune writer produced a pamphlet that detailed Lincoln's life, and sold one million copies.