- Order:

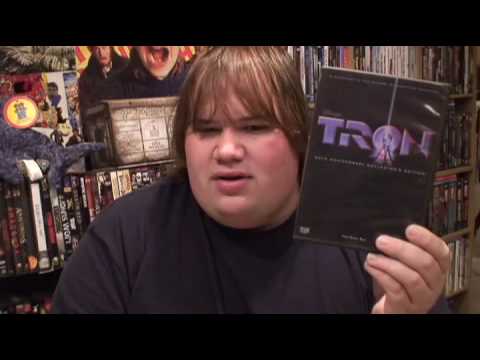

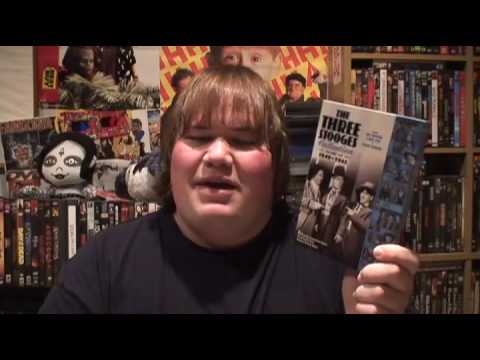

- Duration: 13:39

- Published: 26 Jun 2009

- Uploaded: 22 Mar 2011

- Author: coolduder

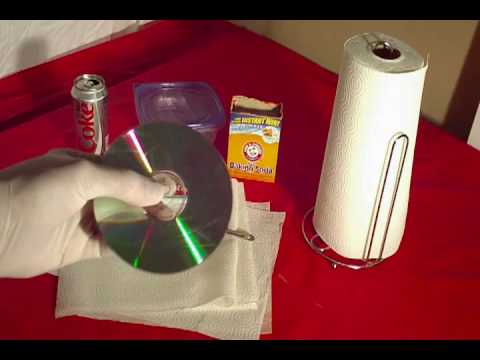

| Name | DVD |

|---|---|

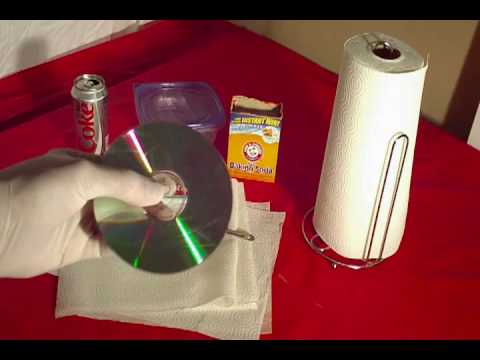

| Caption | DVD-R read/write side |

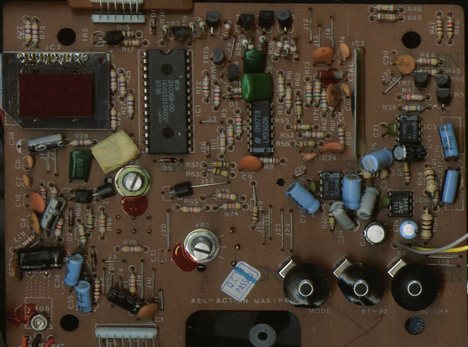

| Type | Optical disc |

| Usage | Standard Definition video Standard definition sound PS2 Xbox Xbox 360 games |

| Capacity | 4.7 GB (single-sided, single-layer – common)8.5-8.7 GB (single-sided, double-layer)9.4 GB (double-sided, single-layer)17.08 GB (double-sided, double-layer – rare) |

| Read | 650 nm laser, 10.5 Mbit/s (1×) |

| Write | 10.5 Mbit/s (1×) |

| Standard | DVD Forum's DVD Books and DVD+RW Alliance specifications |

| Owners/creators | Sony Panasonic Samsung Toshiba Phileps |

Variations of the term DVD often indicate the way data is stored on the discs: DVD-ROM (read only memory) has data that can only be read and not written; DVD-R and DVD+R (recordable) can record data only once, and then function as a DVD-ROM; DVD-RW (re-writable), DVD+RW, and DVD-RAM (random access memory) can all record and erase data multiple times. The wavelength used by standard DVD lasers is 650 nm;

The basic types of DVD (12 cm diameter, single-sided or homogeneous double-sided) are referred to by a rough approximation of their capacity in gigabytes. In draft versions of the specification, DVD-5 indeed held five gigabytes, but some parameters were changed later on as explained above, so the capacity decreased. Other formats, those with 8 cm diameter and hybrid variants, acquired similar numeric names with even larger deviation.

The 12 cm type is a standard DVD, and the 8 cm variety is known as a MiniDVD. These are the same sizes as a standard CD and a mini-CD, respectively. The capacity by surface (MiB/cm2) varies from 6.92 MiB/cm2 in the DVD-1 to 18.0 MiB/cm2 in the DVD-18.

As with hard disk drives, in the DVD realm, gigabyte and the symbol GB are usually used in the SI sense (i.e., 109, or 1,000,000,000 bytes). For distinction, gibibyte (with symbol GiB) is used (i.e., 10243 (230), or 1,073,741,824 bytes).

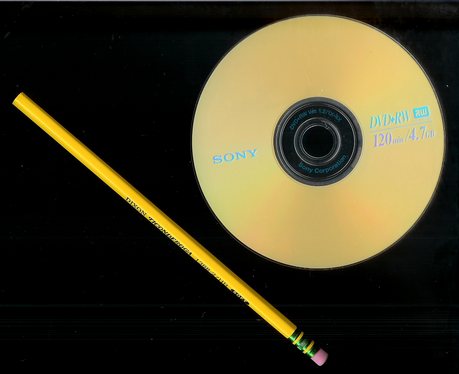

and a 19 cm pencil.]] Each DVD sector contains 2,418 bytes of data, 2,048 bytes of which are user data. There is a small difference in storage space between + and - (hyphen) formats:

DVD uses 650 nm wavelength laser diode light as opposed to 780 nm for CD. This permits a smaller pit to be etched on the media surface compared to CDs (0.74 µm for DVD versus 1.6 µm for CD), allowing for a DVD's increased storage capacity.

In comparison, Blu-ray Disc, the successor to the DVD format, uses a wavelength of 405 nm, and one dual-layer disc has a 50 GB storage capacity.

Writing speeds for DVD were 1×, that is, 1350 kB/s (1,318 KiB/s), in the first drives and media models. More recent models, at 18× or 20×, have 18 or 20 times that speed. Note that for CD drives, 1× means 153.6 kB/s (150 KiB/s), about one-ninth as swift.

{| class="wikitable" |+ DVD drive speeds !rowspan="2"| Drive speed !colspan="3"| Data rate !colspan="2"| ~Write time (min) Many current DVD recorders support dual-layer technology, and the price is now comparable to that of single-layer drives, although the blank media remain more expensive. The recording speeds reached by dual-layer media are still well below those of single-layer media.

There are two modes for dual-layer orientation. With Parallel Track Path (PTP), used on DVD-ROM, both layers start at the inside diameter (ID) and end at the outside diameter (OD) with the lead-out. With Opposite Track Path (OTP), used on many Digital Video Discs, the lower layer starts at the ID and the upper layer starts at the OD, where the other layer ends; they share one lead-in and one lead-out. However, some DVDs also use a parallel track, such as those authored episodically, as in a disc with several separate episodes of a TV series—where more often than not, the layer change is in-between titles and therefore would not need to be authored in the opposite track path fashion.

DVD-Video is a standard for content on DVD media. The format went on sale in Japan on November 1, 1996, in the United States on March 1, 1997, in Europe on October 1, 1998 and in Australia on February 1, 1999.

Consumers initially were also slow to adopt Blu-ray due to the cost. By 2009, 85% of stores were selling Blu-ray Discs. A high-definition television and appropriate connection cables are also required to take advantage of Blu-ray disc. Some analysts suggest that the biggest obstacle to replacing DVD is due to its installed base; a large majority of consumers are satisfied with DVDs. The DVD succeeded because it offered a compelling alternative to VHS. In addition, Blu-ray players are designed to be backward-compatible, allowing older DVDs to be played since the media are physically identical; this differed from the change from vinyl to CD and from tape to DVD, which involved a complete change in physical medium. As of 2010 it is still commonplace for major releases to be issued in "combo pack" format, including both a DVD and a Blu-ray disc (as well as, in many cases, a third disc with an authorized digital copy). Also, some multi-disc sets use Blu-ray for the main feature, but DVD discs for supplementary features (examples of this include the Harry Potter "Ultimate Edition" collections, the 2009 re-release of the 1967 The Prisoner TV series, and a 2007 collection related to Blade Runner).

This situation can be best compared to the changeover from 78 rpm shellac recordings to 45 rpm and 33⅓ rpm vinyl recordings; because the medium used for the earlier format was virtually the same as the latter version (a disc on a turntable, played using a needle), phonographs continued to be built to play obsolete 78s for decades after the format was discontinued. Manufacturers continue to release standard DVD titles as of 2010, and the format remains the preferred one for the release of older television programs and films, with some programs such as needing to be re-scanned to produce a high definition version from the original film recordings (certain special effects were also updated in order to be better received in high-definition viewing). In the case of Doctor Who, a series primarily produced on standard definition videotape between 1963 and 1989, BBC Video reportedly intends to continue issuing DVD-format releases of that series until at least November 2013 (since there would be very little increase in visual quality from upconverting the standard definition videotape masters to high definition).

Durability of DVDs is measured by how long the data may be read from the disc, assuming compatible devices exist that can read it: that is, how long the disc can be stored until data is lost. Five factors affect durability: sealing method, reflective layer, organic dye makeup, where it was manufactured, and storage practices.

The longevity of the ability to read from a DVD+R or DVD-R, is largely dependent on manufacturing quality ranging from 2 to 15 years, and is believed to be an unreliable medium for backup unless great care is taken for storage conditions and handling.

According to the Optical Storage Technology Association (OSTA), "manufacturers claim life spans ranging from 30 to 100 years for DVD, DVD-R and DVD+R discs and up to 30 years for DVD-RW, DVD+RW and DVD-RAM".

Category:Computer storage media Category:Audio storage Category:Video storage Category:DVD Category:120 mm discs Category:Consumer electronics Category:1995 introductions Category:Joint ventures

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Rodney Mullen |

|---|---|

| Birth name | John Rodney Mullen |

| Birth date | August 17, 1966 |

| Birth place | Gainesville, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupation | Professional skateboarder, entrepreneur and author. |

| Education | Biomedical engineering, Mathematics |

| Spouse | Traci Mullen |

| Profession | Skateboarder |

The A-Team folded in 2000 and Mullen went from company founder to company rider under former Maple rider Marc Johnson, who started Enjoi Skateboards. Mullen left Enjoi to head Almost Skateboards with Daewon Song, the company which he still helms and skates for. Mullen's role at Almost includes research and development on new designs and technologies, including Tensor truck in 2000 and experimental and composite deck constructions for Dwindle brands.

In 2002 the World Industries companies, under the holding name Kubic Marketing, were bought out by Globe International for $46 million. Kubic's management remained intact and Mullen began working for Globe International under the Dwindle Distribution brand.

In 2003, Mullen wrote and released his autobiography, entitled The Mutt: How to skateboard and not kill yourself. In late 2003 he was voted as the all-time greatest action sports athlete on the Extreme Sports Channel's Legends of the Extreme countdown.

From 2007 to 2009, Mullen worked to erase his riding stance, allowing him to move from Regular stance to Goofy Stance. In an interview with Tony Hawk, Mullen explained that he had developed problems in his right hip joint and that his transition between stances came out of an effort to favor his leg. He goes on to describe that scar tissue had built up in his joint as a result of habitually hyper-extending his leg while skating. Thirteen out of fourteen nights every two weeks for two years, Mullen would brace his leg in the tire-well of his car and apply pressure to his femur, tearing the scar tissue in the joint; eventually the scar tissue stopped growing back.

In December 2010 Mullen stated in an interview that he is preparing to film a part for the upcoming Almost video.

Mullen is the main "skate double" for Christian Slater in the 1989 movie Gleaming the Cube.

Mullen is also featured in Globe's United By Fate episodic skate video series.

He also made a brief appearance in Episode 10 of the 2007 HBO series John from Cincinnati. He appears in a few cut scenes towards the end, wearing a red shirt and freestyle skateboarding in the background.

Category:American skateboarders Category:Freestyle skateboarders Category:1966 births Category:Living people Category:University of Florida alumni Category:People from Gainesville, Florida

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | New Jack |

|---|---|

| Names | New Jack |

| Height | |

| Weight | |

| Birth date | January 03, 1963 |

| Birth place | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Trainer | Ray Candy |

| Debut | 1992 |

He is known for his willingness to take dangerous bumps and his stiff hardcore wrestling style, often taking high risks and "shooting" on opponents, though he is only known to shoot on opponents who are deemed disrespectful in the ring. He is also known for having his theme song ("Natural Born Killaz" by Ice Cube and Dr. Dre) play throughout his matches in ECW. The inspiration for his ring name came from the movie New Jack City.

Young trained under Ray Candy and debuted in 1992 in the Memphis, Tennessee-based United States Wrestling Association (USWA), where he adopted the name New Jack. He went on to form a tag team, The Gangstas, with Mustafa Saed in Smoky Mountain Wrestling (SMW). The Gangstas took part in several controversial angles, on one occasion using affirmative action to enable them to win matches with a two count pinfall as opposed to the conventional three count. They engaged in a long feud with the Rock 'N Roll Express (Ricky Morton and Robert Gibson). During their stint, the NAACP would picket outside the performance venues because of the "Gangsta" gimmick, claiming that no racial violence had occurred in the Tennessee area for years, and they didn't want the reputation of gangsters to be put into the Tennessee area.

During Jack's time in ECW when he had started to dive from anything and everything, he has stated in an interview he was contacted by the (at the time) WWF to work for them. Jack also stated he wouldn't leave ECW for either the WWF or WCW because they would "water him down" and "make him look weak", in competition to the likes of Steve Austin, The Rock, Triple H, Undertaker and others that where working for the company at that time.

In April 2003, New Jack was in a memorable hardcore match with longtime wrestler Gilberto Melendez (better known as Gypsy Joe). Joe was continuously no-selling New Jack. New Jack also states on a shoot interview that Joe headbutted him in the nose. This caused New Jack to legitimately attack the sexagenarian with a chain, a baseball bat wrapped in barbed wire, and several other weapons. Before the match Jack met Gypsy Joe and went to the booker of the show and asked exactly what he was supposed to do with Joe. Jack was told "Gypsy Joe is as tough as leather", and Jack replied that he wasn't going to lose doller value from this match and won't have either a comedy, or a gimmick match, and told the booker he will kill Gypsy Joe in this hardcore match.

In 2005, New Jack was supposed to wrestle Sandman in a ECW style match, but Danny Demento came out and cut a promo. Sandman came out, cut a promo, then New Jack came out, and the match turned into a Triple Threat ECW style match which New Jack won.

In 2006, New Jack reached an agreement with MTV to participate in their Wrestling Society X television series. He appeared in the Battle Royal to determine contenders for the WSX Championship, directing his focus on fellow ex-ECW alumnus Chris Hamrick. According to New Jack, he and WSX parted ways due to a disagreement backstage.

New Jack ran his own wrestling promotion 2XFW based in Cincinnati, Ohio. There were advertisements for 5 shows, 3 of which were canceled. 2XFW has since ceased operation. There was another attempt at restarting the promotion in November 2009 but things fell through.

New Jack has also competed in KCW (Keystone Championship Wrestling) based in Central Pennsylvania.

On August 8, 2010, New Jack appeared at TNA's ECW reunion show, Hardcore Justice, where he and Mustafa assaulted Team 3D and Joel Gertner after a match.

On December 19, 2010 New Jack appeared at the "Dawg House Bar & Grill" in Hallandale Beach, Florida. New Jack signed autographs and met fans before and during WWE's "Tables, Ladders & Chairs" Pay-Per-View.

New Jack is referenced in the Weezer song "El Scorcho". The line "watchin' Grunge legdrop New Jack through a press table" was derived from a caption for a photograph of New Jack fighting wrestler Johnny Grunge that was published in Pro Wrestling Illustrated.

New Jack took part in a shoot interview with The Iron Sheik and The Honky Tonk Man where the subject was Chris Benoit's murder-suicide. New Jack commented that nothing could excuse what Benoit had done and all people on WWE and elsewhere who were making excuses for him were hypocrites. He also thought it was ironic how Extreme Championship Wrestling was seen as violent and dangerous wrestling when he was working there and still only one person died under New Jack's time with the company, whereas WWE was "averaging three a year." (It should be noted that so far only 4 performers, including Benoit, have died under while under WWE contract. All four deaths happened across a 10 year period). He also has a DVD documentary called New Jack Hardcore: The History.

New Jack did a DVD interview with The Sandman (Jim Fullington) and Raven (Scott Levy) for Pro Wrestling Insider.

New Jack recently made his hip hop recording debut. He contributed several verses to indie rapper Duckman's new album Duckman for Presidente. An animated commercial for the album featuring a cartoon version of New Jack was recently released. New Jack's voice is featured in the commercial and he tells listeners to "buy the cd or I'll stab your ass". In the popular video game the player can earn a call sign titled New Jack, referring to when he stabbed his opponent.

New Jack has a radio show on BlogTalkRadio airing Wednesdays 10pm to 11pm.

New Jack is currently in a relationship with former WWE Diva Terri Runnels.

New Jack on MySpace

Category:1963 births Category:African American professional wrestlers Category:American professional wrestlers Category:American television actors Category:People from Atlanta, Georgia Category:Living people

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

| Name | Fred Astaire |

|---|---|

| Caption | in You'll Never Get Rich (1941) |

| Birth name | Frederick Austerlitz |

| Birth date | May 10, 1899 |

| Birth place | Omaha, Nebraska,United States |

| Death date | June 22, 1987 |

| Death place | Los Angeles, California,United States |

| Occupation | Actor, dancer, singer, choreographer |

| Years active | 1917–1981 |

| Spouse | Phyllis Livingston Potter (1933–1954) Robyn Smith(1980–1987) |

After the close of Funny Face, the Astaires went to Hollywood for a screen test (now lost) at Paramount Pictures, but were not considered suitable for films.

They split in 1932 when Adele married her first husband, Lord Charles Arthur Francis Cavendish, a son of the Duke of Devonshire. Fred Astaire went on to achieve success on his own on Broadway and in London with Gay Divorce, while considering offers from Hollywood. The end of the partnership was traumatic for Astaire, but stimulated him to expand his range. Free of the brother-sister constraints of the former pairing and with a new partner (Claire Luce), he created a romantic partnered dance to Cole Porter's "Night and Day", which had been written for Gay Divorce. Luce stated that she had to encourage him to take a more romantic approach: "Come on, Fred, I'm not your sister, you know." The success of the stage play was credited to this number, and when recreated in the film version of the play The Gay Divorcee (1934), it ushered in a new era in filmed dance. Astaire later insisted that the report had actually read: "Can't act. Slightly bald. Also dances". However, this did not affect RKO's plans for Astaire, first lending him for a few days to MGM in 1933 for his Hollywood debut, where he appeared as himself dancing with Joan Crawford in the successful musical film Dancing Lady.

On his return to RKO Pictures, he got fifth billing alongside Ginger Rogers in the 1933 Dolores del Río vehicle Flying Down to Rio. In a review, Variety magazine attributed its massive success to Astaire's presence: "The main point of Flying Down to Rio is the screen promise of Fred Astaire ... He's assuredly a bet after this one, for he's distinctly likable on the screen, the mike is kind to his voice and as a dancer he remains in a class by himself. The latter observation will be no news to the profession, which has long admitted that Astaire starts dancing where the others stop hoofing."

Having already been linked to his sister Adele on stage, Astaire was initially very reluctant to become part of another dance team. He wrote his agent, "I don't mind making another picture with her, but as for this team idea it's out! I've just managed to live down one partnership and I don't want to be bothered with any more." He was persuaded by the obvious public appeal of the Astaire-Rogers pairing. The partnership, and the choreography of Astaire and Hermes Pan, helped make dancing an important element of the Hollywood film musical. Astaire and Rogers made ten films together, including The Gay Divorcee (1934), Roberta (1935), Top Hat (1935), Follow the Fleet (1936), Swing Time (1936), Shall We Dance (1937), and Carefree (1938). Six out of the nine Astaire-Rogers musicals became the biggest moneymakers for RKO; all of the films brought a certain prestige and artistry that all studios coveted at the time. Their partnership elevated them both to stardom; as Katharine Hepburn reportedly said, "He gives her class and she gives him sex." First, he insisted that the (almost stationary) camera film a dance routine in a single shot, if possible, while holding the dancers in full view at all times. Astaire famously quipped: "Either the camera will dance, or I will." Astaire maintained this policy from The Gay Divorcee (1934) onwards (until overruled by Francis Ford Coppola, who directed Finian's Rainbow (1968), Astaire's last film musical). Hannah Hyam consider Rogers to have been Astaire's greatest dance partner, while recognizing that some of his later partners displayed superior technical dance skills, a view shared

Astaire was still unwilling to have his career tied exclusively to any partnership, however. He negotiated with RKO to strike out on his own with A Damsel in Distress in 1937 with an inexperienced, non-dancing Joan Fontaine, unsuccessfully as it turned out. He returned to make two more films with Rogers, Carefree (1938) and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939). While both films earned respectable gross incomes, they both lost money due to increased production costs and Astaire left RKO. Rogers remained and went on to become the studio's hottest property in the early forties. They were reunited in 1949 at MGM for their final outing, The Barkleys of Broadway.

He made two pictures with Rita Hayworth, the daughter of his former vaudeville dance idols, the Cansinos: the first You'll Never Get Rich (1941) catapulted Hayworth to stardom and provided Astaire with his first opportunity to integrate Latin-American dance idioms into his style, taking advantage of Hayworth's professional Latin dance pedigree. His second film with Hayworth, You Were Never Lovelier (1942) was equally successful, and featured a duet to Kern's "I'm Old Fashioned" which became the centerpiece of Jerome Robbins's 1983 New York City Ballet tribute to Astaire. He next appeared opposite the seventeen-year-old Joan Leslie in the wartime drama The Sky's the Limit (1943) where he introduced Arlen and Mercer's "One for My Baby" while dancing on a bar counter in a dark and troubled routine. This film which was choreographed by Astaire alone and achieved modest box office success, represented an important departure for Astaire from his usual charming happy-go-lucky screen persona and confused contemporary critics.

His next partner, Lucille Bremer, was featured in two lavish vehicles, both directed by Vincente Minnelli: the fantasy Yolanda and the Thief which featured an avant-garde surrealistic ballet, and the musical revue Ziegfeld Follies (1946) which featured a memorable teaming of Astaire with Gene Kelly to "The Babbit and the Bromide", a Gershwin song Astaire had introduced with his sister Adele back in 1927. While Follies was a hit, Yolanda bombed at the box office and Astaire, ever insecure and believing his career was beginning to falter surprised his audiences by announcing his retirement during the production of Blue Skies (1946), nominating "Puttin' on the Ritz" as his farewell dance.

After announcing his retirement in 1946, Astaire concentrated on his horse-racing interests and went on to found the Fred Astaire Dance Studios in 1947 — which he subsequently sold in 1966.

During 1952 Astaire recorded The Astaire Story, a four volume album with a quintet led by Oscar Peterson. The album provided a musical overview of Astaire's career, and was produced by Norman Granz. The Astaire Story later won the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 1999, a special Grammy award to honor recordings that are at least twenty-five years old, and that have "qualitative or historical significance." Astaire further observes:

Working out the steps is a very complicated process — something like writing music. You have to think of some step that flows into the next one, and the whole dance must have an integrated pattern. If the dance is right, there shouldn't be a single superfluous movement. It should build to a climax and stop!"

With very few exceptions, Astaire created his routines in collaboration with other choreographers, primarily Hermes Pan. They would often start with a blank slate:

"For maybe a couple of days we wouldn't get anywhere — just stand in front of the mirror and fool around ... Then suddenly I'd get an idea or one of them would get an idea ... So then we'd get started ... You might get practically the whole idea of the routine done that day, but then you'd work on it, edit it, scramble it, and so forth. It might take sometimes as long as two, three weeks to get something going."

Frequently, a dance sequence was built around two or three principal ideas, sometimes inspired by his own steps or by the music itself, suggesting a particular mood or action. Many of his dances were built around a "gimmick", such as dancing on the walls in "Royal Wedding," or dancing with his shadows in Swing Time, that he or his collaborator had thought up earlier and saved for the right situation. They would spend weeks creating all the dance sequences in a secluded rehearsal space before filming would begin, working with a rehearsal pianist (often the composer Hal Borne) who in turn would communicate modifications to the musical orchestrators.

His perfectionism was legendary; however, his relentless insistence on rehearsals and retakes was a burden to some. When time approached for the shooting of a number, Astaire would rehearse for another two weeks, and record the singing and music. With all the preparation completed, the actual shooting would go quickly, conserving costs. Astaire agonized during the entire process, frequently asking colleagues for acceptance for his work, as Vincente Minnelli stated, "He lacks confidence to the most enormous degree of all the people in the world. He will not even go to see his rushes ... He always thinks he is no good." As Astaire himself observed, "I've never yet got anything 100% right. Still it's never as bad as I think it is."

Although he viewed himself as an entertainer first and foremost, his consummate artistry won him the admiration of such twentieth century dance legends as Gene Kelly, George Balanchine, the Nicholas Brothers, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Margot Fonteyn, Bob Fosse, Gregory Hines, Rudolf Nureyev, Michael Jackson and Bill Robinson. Balanchine compared him to Bach, describing him as "", while for Baryshnikov he was "".

Astaire was a songwriter of note himself, with "I'm Building Up to an Awful Letdown" (written with lyricist Johnny Mercer) reaching number four in the Hit Parade of 1936. He recorded his own "It's Just Like Taking Candy from a Baby" with Benny Goodman in 1940, and nurtured a lifelong ambition to be a successful popular song composer.

Built in 1905, the Gottlieb Storz Mansion in Astaire's hometown of Omaha includes the "Adele and Fred Astaire Ballroom" on the top floor, which is the only memorial to their Omaha roots.

Astaire is referenced in the 2003 animated feature, The Triplets of Belleville, in which he is eaten by his shoes after a fast-paced dance act.

Always immaculately turned out, Astaire remained something of a male fashion icon even into his later years, eschewing his trademark top hat, white tie and tails (which he never really cared for) in favor of a breezy casual style of tailored sports jackets, colored shirts, cravats and slacks — the latter usually held up by the idiosyncratic use of an old tie in place of a belt.

Astaire married for the first time in 1933, to the 25-year-old Phyllis Potter (née Phyllis Livingston Baker, 1908–1954), a Boston-born New York socialite and former wife of Eliphalet Nott Potter III (1906–1981), after pursuing her ardently for roughly two years. Phyllis's death from lung cancer, at the age of 46, ended 21 years of a blissful marriage and left Astaire devastated. Astaire attempted to drop out of the film Daddy Long Legs (1955), offering to pay the production costs to date, but was persuaded to stay.

In addition to Phyllis Potter's son, Eliphalet IV, known as Peter, the Astaires had two children. Fred, Jr. (born 1936) appeared with his father in the movie Midas Run, but became a charter pilot and rancher instead of an actor. Ava Astaire McKenzie (born 1942) remains actively involved in promoting her late father's heritage.

His friend David Niven described him as "a pixie — timid, always warm-hearted, with a penchant for schoolboy jokes." Astaire was a lifelong golf and Thoroughbred horse racing enthusiast. In 1946 his horse Triplicate won the prestigious Hollywood Gold Cup and San Juan Capistrano Handicap. He remained physically active well into his eighties. At age seventy-eight, he broke his left wrist while riding his grandson's skateboard.

He remarried in 1980 to Robyn Smith, a jockey almost 45 years his junior. Smith was a jockey for Alfred G. Vanderbilt II.

Astaire died from pneumonia on June 22, 1987. He was interred in the Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, California. One last request of his was to thank his fans for their years of support.

Astaire has never been portrayed on film. He always refused permission for such portrayals, saying, "However much they offer me — and offers come in all the time — I shall not sell." Astaire's will included a clause requesting that no such portrayal ever take place; he commented, "It is there because I have no particular desire to have my life misinterpreted, which it would be."

Category:1899 births Category:1987 deaths Category:American Episcopalians Category:Academy Honorary Award recipients Category:American ballroom dancers Category:20th-century actors Category:Traditional pop music singers Category:American crooners Category:American choreographers Category:American people of Austrian descent Category:American actors of German descent Category:American people of Jewish descent Category:American film actors Category:American tap dancers Category:BAFTA winners (people) Category:BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actor Category:Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Category:Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Category:California Republicans Category:Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners Category:Deaths from pneumonia Category:Emmy Award winners Category:Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Category:People from Omaha, Nebraska Category:Burials at Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery Category:Kennedy Center honorees Category:National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame inductees Category:Actors from Omaha, Nebraska Category:RCA Victor artists Category:MGM Records artists Category:Vaudeville performers Category:American racehorse owners and breeders Category:Infectious disease deaths in California Category:Film choreographers

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.

![[DVD] Radiohead - Live From The Basement [Full Show] [DVD] Radiohead - Live From The Basement [Full Show]](http://web.archive.org./web/20110405193151im_/http://i.ytimg.com/vi/k8byXSML4bY/0.jpg)