- Order:

- Duration: 2:11

- Published: 10 Nov 2007

- Uploaded: 03 Jul 2011

- Author: perfectlittlelife

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration, but as it carried strong religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850s changing attitudes eventually resulted in the toning down of much of the day's anti-Catholic rhetoric, and in 1859 the original 1606 legislation was repealed. Eventually, the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events, centred around a bonfire and extravagant firework displays.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution, although celebrations continue in some Commonwealth nations. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs like Samhain are disputed, although another old celebration, Halloween, has lately increased in popularity, and according to some writers, may threaten the continued observance of 5 November.

Little is known about the earliest celebrations. In settlements such as Carlisle, Norwich and Nottingham, corporations provided music and artillery salutes. Canterbury celebrated 5 November 1607 with 106 pounds of gunpowder and 14 pounds of match, and three years later food and drink was provided for local dignitaries, as well as music, explosions and a parade by the local militia. Even less is known of how the occasion was first commemorated by the general public, although records indicate that in Protestant Dorchester a sermon was read, the church bells rung, and bonfires and fireworks lit.

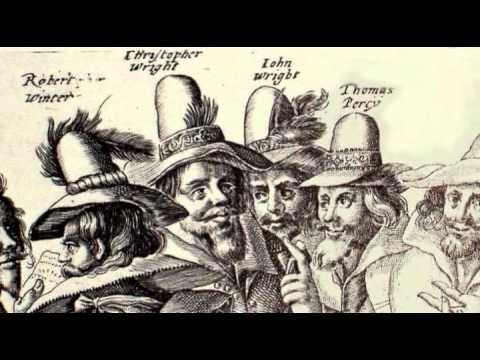

What unity English Protestants had shared in 1606 began to fade when in 1625 James's son, the future Charles I, married the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France. Puritans reacted to the marriage by issuing a new prayer to warn against rebellion and Catholicism, and on 5 November that year, effigies of the pope and the devil were burnt, the earliest such report of this practice and the beginning of centuries of tradition.|group="nb"}} During Charles's reign Gunpowder Treason Day became increasingly partisan. Between 1629 and 1640 he ruled without Parliament, and he seemed to support Arminianism, regarded by Puritans like Henry Burton as a step toward Catholicism. By 1636, under the leadership of the Arminian Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, the English church was trying to use 5 November to denounce all seditious practices, and not just popery. Puritans went on the defensive, some pressing for further reformation of the Church. A display in 1647 at Lincoln's Inn Fields commemorated "God's great mercy in delivering this kingdom from the hellish plots of papists", and included fireballs burning in the water (symbolising a Catholic association with "infernal spirits") and fireboxes, their many rockets suggestive of "popish spirits coming from below" to enact plots against the king. Effigies of Fawkes and the pope were present, the latter represented by Pluto, Greek god of the underworld.

Following Charles I's execution in 1649, the country's new republican regime remained undecided on how to treat 5 November. Unlike the old system of religious feasts and State anniversaries, it survived, but as a celebration of parliamentary government and Protestantism, and not of monarchy. demanding money from coach occupants for alcohol and bonfires. The burning of effigies, largely unknown to the Jacobeans, continued in 1673 when Charles's brother, the Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. In response, accompanied by a procession of about 1,000 people, the apprentices fired an effigy of the Whore of Babylon, bedecked with a range of papal symbols. Similar scenes occurred over the following few years. In 1677 elements of Queen Elizabeth's Accession Day celebration of 17 November were incorporated into the Fifth, with the burning of large bonfires, a large effigy of the pope—his belly filled with live cats "who squalled most hideously as soon as they felt the fire"—and two effigies of devils "whispering in his ear". Two years later, as the exclusion crisis was reaching its zenith, an observer noted the "many bonfires and burning of popes as has ever been seen". Violent scenes in 1682 forced London's militia into action, and to prevent any repetition the following year a proclamation was issued, banning bonfires and fireworks.

Fireworks were also banned under James II, who became king in 1685. Attempts by the government to tone down Gunpowder Treason Day celebrations were, however, largely unsuccessful, and some reacted to a ban on bonfires in London (born from a fear of more burnings of the pope's effigy) by placing candles in their windows, "as a witness against Catholicism". When James was deposed in 1688 by William of Orange—who importantly, landed in England on 5 November—the day's events turned also to the celebration of freedom and religion, with elements of anti-Jacobitism. While the earlier ban on bonfires was politically motivated, a ban on fireworks was maintained for safety reasons, "much mischief having been done by squibs".

, printed in November that year.]] At some point in the 18th century and for reasons that are unclear, it became customary to burn Guy Fawkes in effigy, rather than the pope. Gradually, Gunpowder Treason Day had turned into Guy Fawkes Day. In 1790 The Times reported instances of children "...begging for money for Guy Faux", and a report of 4 November 1802 described how "a set of idle fellows ... with some horrid figure dressed up as a Guy Faux" were convicted of begging and receiving money, and committed to prison as "idle and disorderly persons". The Fifth had become "a polysemous occasion, replete with polyvalent cross-referencing, meaning all things to all men".

On several occasions during the 19th century The Times reported that the tradition was in decline, being "of late years almost forgotten", but in the opinion of historian David Cressy, such reports reflected "other Victorian trends", including a lessening of Protestant religious zeal—not general observance of the Fifth. The traditional denunciations of Catholicism had been in decline since the early 18th century, and were thought by many, including Queen Victoria, to be outdated, Effigies of the twelve new English Catholic bishops were paraded through Exeter, already the scene of severe public disorder on each anniversary of the Fifth. Gradually, however, such scenes became less popular. The thanksgiving prayer of 5 November contained in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was abolished, with little resistance in Parliament, and in March 1859 the Anniversary Days Observance Act repealed the original 1606 Act. As the authorities dealt with the worst excesses, public decorum was gradually restored. The sale of fireworks was restricted, and the Guildford "guys" were neutered in 1865, although this was too late for one constable, who died of his wounds. Violence continued in Exeter for some years, peaking in 1867, when incensed by rising food prices and banned from firing their customary bonfire, a mob was twice in one night driven from Cathedral Close by armed infantry. Further riots occurred in 1879, but there were no more bonfires in Cathedral Close after 1894. Elsewhere, sporadic instances of public disorder persisted late into the 20th century, accompanied by large numbers of firework-related accidents, but a national Firework Code and improved public safety has in most cases brought an end to such things.

near Dudley, on 6 November 2010]] Organised entertainments became popular in the late 19th century, and 20th-century pyrotechnic manufacturers renamed Guy Fawkes Day as Firework Night. Sales of fireworks dwindled somewhat during the First World War, but resumed in the following peace. At the start of the Second World War celebrations were again suspended, resuming in November 1945. For many families Guy Fawkes Night became a domestic celebration, and children often congregated on street corners, accompanied by their own effigy of Guy Fawkes. This was sometimes ornately dressed and sometimes a barely-recognisable bundle of straw and rags, but the custom of begging for a "penny for the Guy" has lately almost completely disappeared. In contrast, some older customs still survive; in Ottery St Mary men chase each other through the streets with lit tar barrels, and since 1679 Lewes has been the setting of some of England's most extravagant 5 November celebrations, the Lewes Bonfire.

Generally, modern 5 November celebrations are run by local charities and other organisations, with paid admission and controlled access. Author Martin Kettle, writing in The Guardian, bemoaned an "occasionally nannyish" attitude to fireworks which discourages people from holding firework displays in their back gardens, and an "unduly sensitive attitude" toward the anti-Catholic sentiment once so prominent on Guy Fawkes Night. David Cressy summarised the modern celebration with these words: "the rockets go higher and burn with more colour, but they have less and less to do with memories of the Fifth of November ...it might be observed that Guy Fawkes' Day is finally declining, having lost its connection with politics and religion. But we have heard that many times before."

}}

Another celebration involving fireworks, the five-day Hindu festival of Diwali (normally observed between mid-October and November), in 2010 began on 5 November. This led The Independent to comment on the similarities between the two, its reporter Kevin Rawlinson wondering "which fireworks will burn brightest".

The passage in 1774 of the Quebec Act, which guaranteed French Canadians free practice of Catholicism in the Province of Quebec, provoked complaints from some Americans that the British were introducing "Popish principles and French law" to Quebec. These fears were bolstered by the opposition from the Church in Europe to American independence, threatening a revival of Pope Day. Commenting in 1775, George Washington was less than impressed by the thought of any such resurrections, forbidding any under his command from participating:

}}

Generally, following Washington's complaint, American colonists stopped observing Pope Day, although according to The Bostonian Society some citizens of Boston celebrated it on one final occasion, in 1776. The tradition continued in Salem as late as 1817, and was still observed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1892. In the late 18th century, effigies of prominent figures such as two Prime Ministers of Great Britain, the Earl of Bute and Lord North, and the American traitor General Benedict Arnold, were also burnt. In the 1880s bonfires were still being burnt in some New England coastal towns, although no longer to commemorate the failure of the Gunpowder Plot. In the area around New York, stacks of barrels were burnt on election day eve, which after 1845 was a Tuesday early in November.

;Footnotes

;Bibliography

Category:Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom Category:Autumn traditions Category:British traditions Category:Holidays in the United Kingdom Category:November observances

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons CC-BY-SA License. This text was originally published on Wikipedia and was developed by the Wikipedia community.